Ensuring the rights of nomadic seafarers

Ensuring the rights of nomadic seafarers

As a young girl, Wanita Arajani lived the traditional life of her nomadic people, who roamed from the Philippines to Malaysia and Indonesia by boat, living from the sea. Few went to school, learned to read or write, or had citizenship.

“Before, having a birth certificate was not relevant or a priority,” explains Wanita, now a grandmother in her 70s, as she sits outside the wooden house on stilts, east of Zamboanga city in the Philippines where her family now lives.

That life changed abruptly in 2013, when the Zamboanga conflict erupted after armed militants attempted to assert autonomy. Ensuing clashes drove her family and thousands of others to seek shelter in government-run evacuation centres.

Teachers at the evacuation centres encouraged families to send their children to nearby schools. It was then that Wanita learned that her granddaughter would need a birth certificate to be able to progress through the education system.

She also discovered that documentation would be vital for family members to avoid arrest during security sweeps, and to allow the long-marginalized community access to health care and housing in the Philippines.

“It has been difficult for us to access services and we always feared discrimination."

“It has been difficult for us to access services and we always feared discrimination, because we were Sama Bajau,” says Wanita. “But when we get a birth certificate, we will feel more respected and be able to live life with dignity. I will feel valued as a citizen.”

The Philippines is the only country in South-East Asia to have adopted a national action plan to end statelessness. It has identified the Sama Bajau as one of five population groups at risk. It is thought there are 10,000 to 15,000 Sama Bajau living in Zamboanga alone, around 85 per cent of whom have no birth certificates.

As part of a concerted push to resolve their situation, UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, has worked closely with the community, the local government authorities and the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples since 2016.

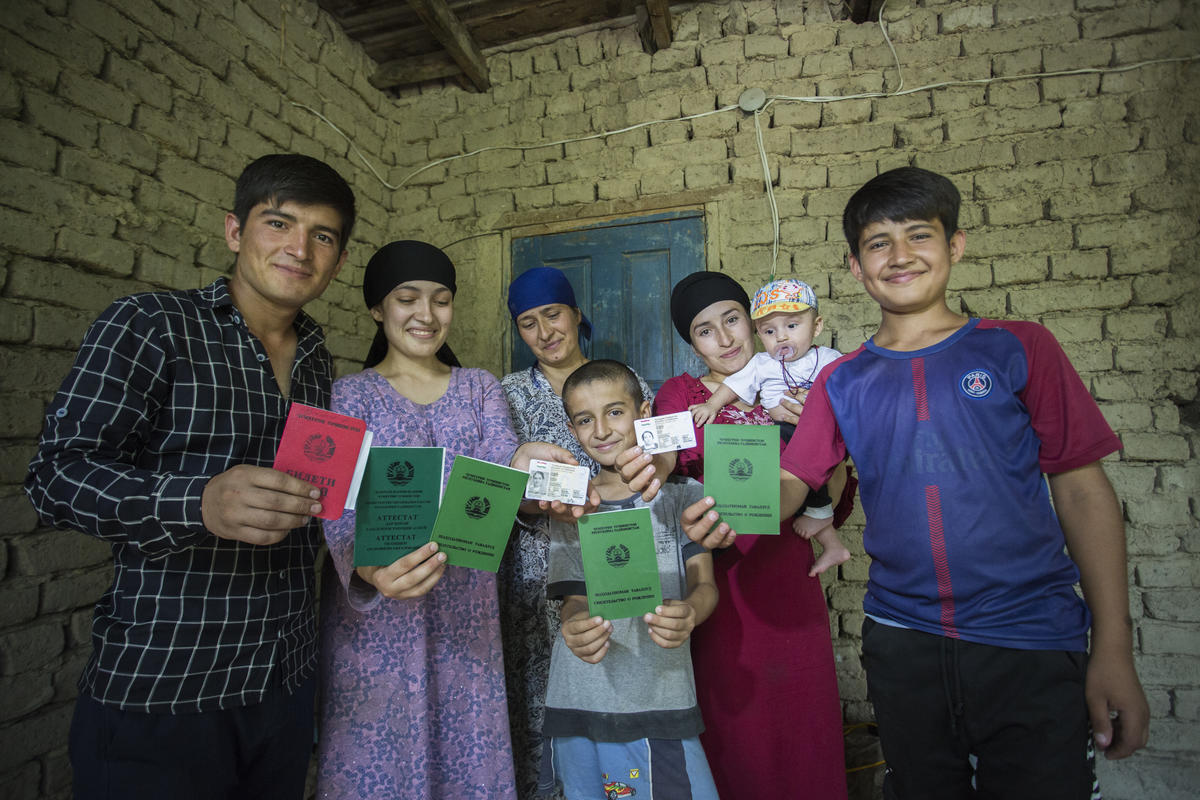

A pilot project supported by UNHCR and UNICEF, which begins in October, seeks to register 1,500 people in the community. Working closely with the government authorities, including a mobile unit of the Civil Registrar’s Office, the aim is to issue families with documentation by mid-December.

“When they get their identification documents, it gives them better opportunities, particularly when it comes to getting an education and learning to read and write,” says Meriam Palma, a UNHCR field associate for protection, who works on statelessness issues.

“It’s an important tool for them to be able to assert their rights as a tribe and as a people,” she adds.

Before the drive got underway, Wanita had already succeeded in obtaining a birth certificate for her 15-year-old granddaughter, Pirina, which she needed to be allowed to graduate from elementary school and attend junior high.

“I’m the only one in the family to have completed my elementary schooling,” says Pirina, whose graduation photo hangs in pride of place on the wall of the family home.

She says that she loves school because she likes learning, and the teachers are kind and good to her. She is also clear about how having a birth certificate will help her in the future. “It will make it easier to have the chance to apply for jobs and find work.”

“You are our family’s hope,” interjects her grandmother. “Because I’m illiterate, we are clinging on to you to help us."

Wanita is also excited that the rest of her family will soon benefit from the pilot project.

“The future is clearer and brighter. It’s like you are giving us a kerosene light to brighten our path.”

“I’m so happy. I will have peace of mind,” she says. “Although it’s too late for my sons and daughters, I’ll focus on trying to make sure all my grandsons and granddaughters can go to school. I feel it’s their new hope to have a better life. I’ll do my best to send them to school as long as I’m alive.”

The Sama Bajau regard the sea as their home and living far from it was not their choice. They were compelled to move under the National Integrated Protected Areas System Act, which declared protected areas, including the coast where they live as no build zones. But having rights on dry land is also vital to them.

“The future is clearer and brighter. It’s like you are giving us a kerosene light to brighten our path and give us hope,” she says with a big smile.

Worldwide millions of people like Wanita are at risk of statelessness and millions more are not recognized by any country as citizens and are stateless. This can mean that basic things that most people take for granted, such as free movement, access to medical treatment, education, seeking a job or even buying a SIM card for a mobile phone, can be a daily battle.

To find out more about how you can make a difference to the lives of people like her, join UNHCR’s #IBelong Campaign to End Statelessness in 10 years.