New handbook on statelessness addresses 11 million "forgotten" people

New handbook on statelessness addresses 11 million "forgotten" people

GENEVA, October 20 (UNHCR) - The UN refugee agency and the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) this week launched a practical handbook for parliamentarians to address nationality and statelessness, phenomena which adversely affect the lives of millions of men, women and children around the world.

A stateless person is someone who is not recognized by any country as a citizen. There are an estimated 11 million people in the world in this situation. They are effectively trapped in a legal limbo, enjoying minimal or no access to national or international legal protection or to such basic rights as health and education. Stateless people have been described as "the ultimate forgotten people."

Hannah Arendt, the German Jewish philosopher and refugee, had strong feelings on the subject, no doubt as a result of her own experience of statelessness after fleeing Nazi Germany: "To be stripped of citizenship is to be stripped of worldliness; it is like returning to a wilderness as cavemen or savages," she wrote in The Origins of Totalitarianism. "... They could live and die without leaving any trace, without having contributed anything to the common world."

Arendt ended up a U.S. citizen, but many less fortunate people are born stateless and remain stateless until the day they die.

Lara, a formerly stateless woman, describes the corrosive effect of statelessness on the morale of the individual: "Being said 'No' to by the country where I live; being said 'No' to by the country where I was born; being said 'No' to by the country where my parents are from; hearing 'you do not belong to us' continuously! I feel I am nobody and don't even know why I'm living. Being stateless, you are always surrounded by a sense of worthlessness."

The handbook for parliamentarians, which was launched during a panel discussion on nationality and statelessness at the 113th Assembly of the IPU in Geneva, suggests practical steps and concrete actions to prevent or solve situations of statelessness.

The preferred solution is the acquisition of an effective nationality, a right enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Among recent successful examples are the granting of Sri Lankan nationality to more than 190,000 Estate Tamils in 2004, and the recent acquisition of citizenship by ethnic Albanians and Roma in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. In both of these situations, UNHCR worked with the authorities to promote access to citizenship.

International conventions on statelessness were established in 1954 (Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons) and 1961 (Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness). As the UN High Commissioner for Refugees António Guterres pointed out during the launch of the handbook, the importance of the 1954 Convention lies in the fact that it provides basic rights to people in a situation where they lack access to these rights, and that is one of the reasons why accession to this treaty is so crucial.

"All stateless persons should have the chance of gaining an effective nationality," Guterres said. "Refugees make the headlines as they are the visible victims of persecution and conflicts. The plight of stateless persons is in many ways similar, but they are almost invisible."

Besides High Commissioner Guterres, speakers at the panel included the First Vice-President of the Chilean National Congress, Mr. Alejandro Navarro; the Director of the Innocenti Research Centre of the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Ms. Marta Santo Pais; and Mr. Gerard-René de Groot, a professor at the University of Maastricht. The discussion was moderated by UNHCR's Director of International Protection, Erika Feller.

UNHCR welcomed announcements made by parliamentary delegations from Egypt and Morocco about the introduction of new laws in their countries which allow the acquisition of nationality by children from both parents on an equal basis.

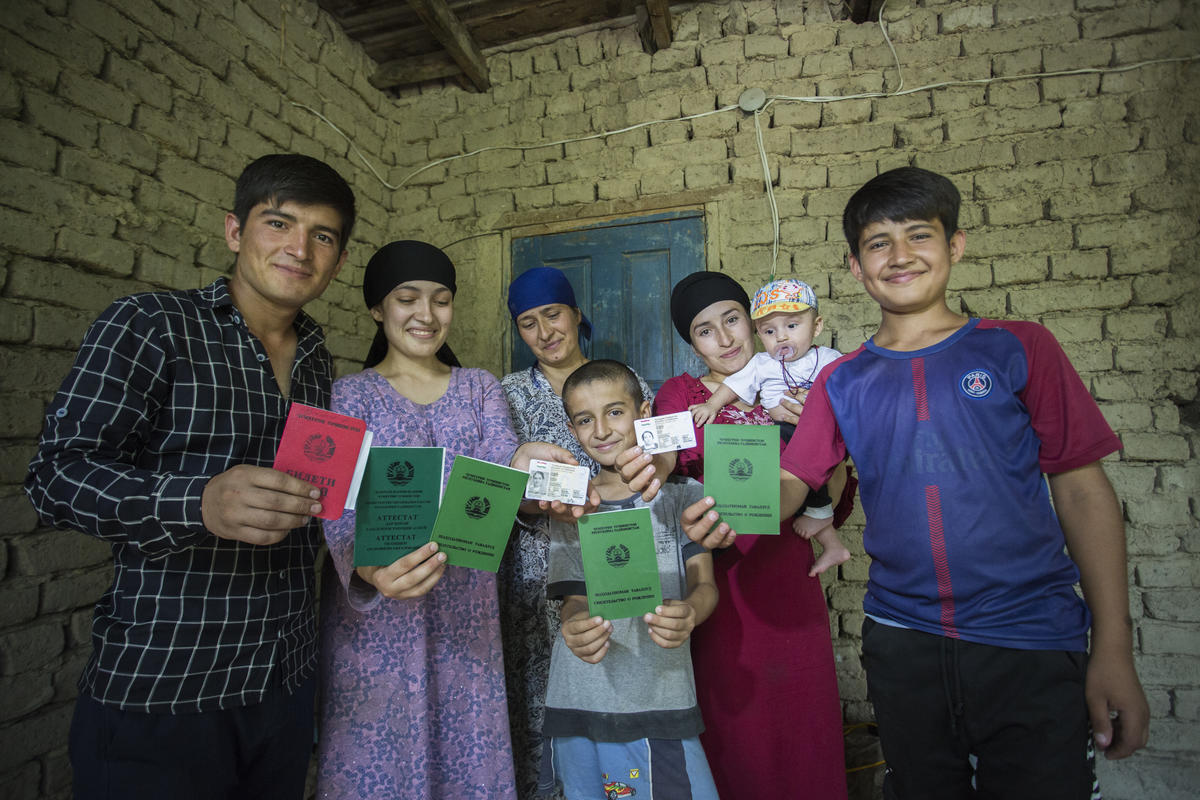

A key measure to prevent statelessness suggested in the handbook is to ensure that all children are registered at birth.

"Millions of children are never registered at birth," said Philippe Leclerc, head of UNHCR's Statelessness Unit. "The effects of this bureaucratic failure can be catastrophic for the individual child. It can make them much more vulnerable to trafficking and other forms of exploitation. It can ruin their entire lives. And it is avoidable."

With this joint publication, UNHCR and the IPU hope that Parliaments will take appropriate action to address situations which so far have remained unsolved. Two examples - among many others - are those of the Biharis in Bangladesh and that of the Bidoon in the Persian Gulf region.

In 1974, and in subsequent resolutions, the UN General Assembly mandated the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as the agency responsible for promoting the reduction of statelessness and the enjoyment of basic rights by stateless people.

Established in 1889 and with its Headquarters in Geneva, the IPU is the oldest multilateral political organization, currently bringing together 141 affiliated parliaments and seven associated regional assemblies.