New Campaign: UNHCR launches global campaign for the stateless millions

New Campaign: UNHCR launches global campaign for the stateless millions

GENEVA, August 25 (UNHCR) - The UN refugee agency today launches a global campaign to promote action against statelessness, a scourge for millions of people worldwide.

"These people are in desperate need of help because they live in a nightmarish legal limbo," High Commissioner for Refugees António Guterres said. "This makes them some of the most excluded people in the world. Apart from the misery caused to the people themselves, the effect of marginalizing whole groups of people across generations creates great stress in the societies they live in and is sometimes a source of conflict," he added in a message to launch the campaign, which comes ahead of the 50th anniversary on Tuesday of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness.

UNHCR estimates that there are up to 12 million stateless people in the world today, but defining exact numbers is problematic. Inconsistent reporting combined with different definitions of statelessness means the true scale of the problem remains elusive.

“These people are in desperate need of help because they live in a nightmarish legal limbo. This makes them some of the most excluded people in the world.António Guterres UN High Commissioner for Refugees”

“These people are in desperate need of help because they live in a nightmarish legal limbo. This makes them some of the most excluded people in the world.António Guterres UN High Commissioner for Refugees”

To overcome this, UNHCR is raising awareness about the international legal definition while improving its own methods for gathering data on stateless populations. UNHCR has found the problem is particularly acute in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, Eastern Europe and the Middle East. However pockets of statelessness exist throughout the world and it is a problem that crosses all borders and walks of life.

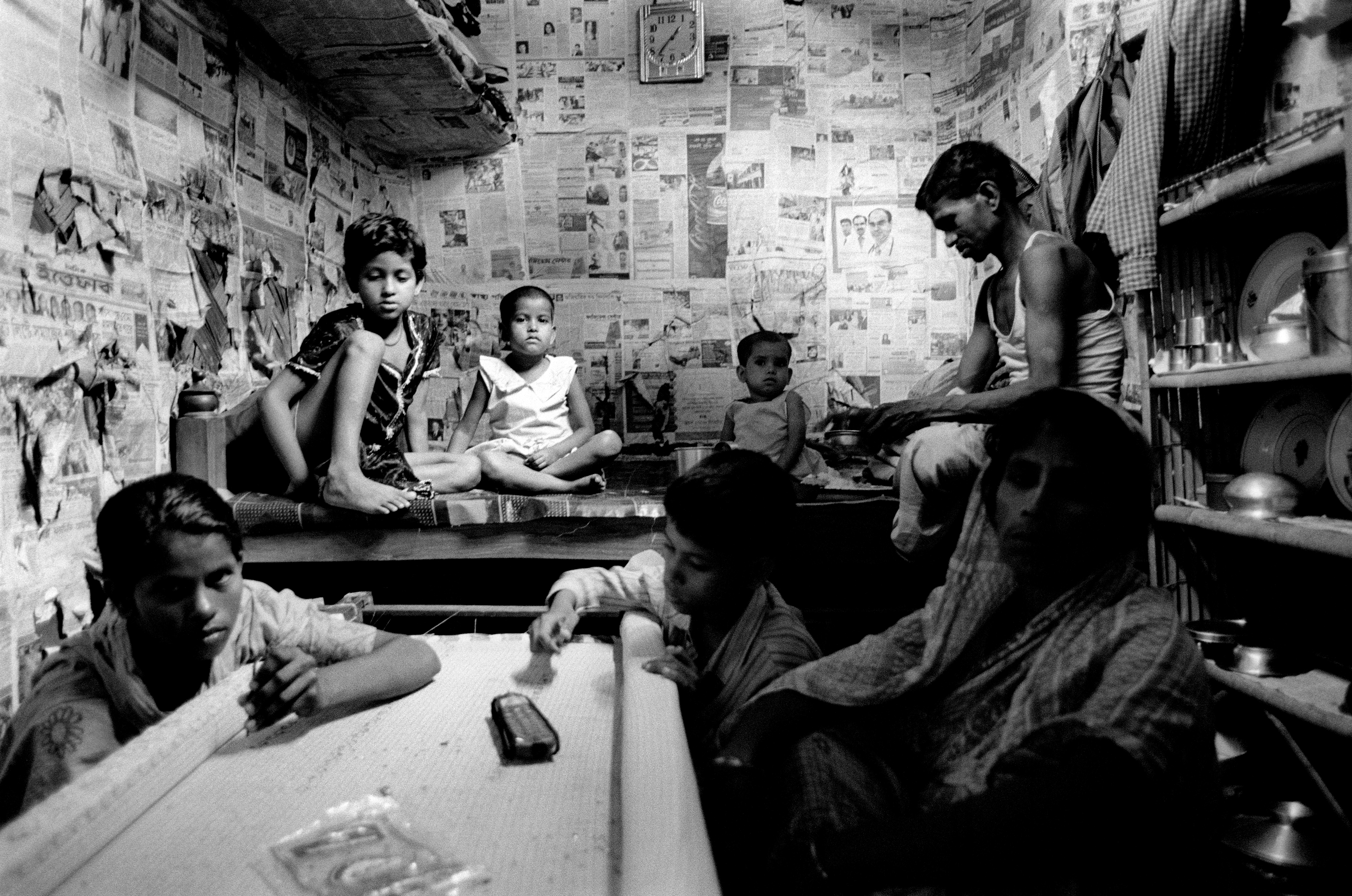

There are numerous causes of statelessness, many of them entrenched in legalities, but the human consequences can be dramatic. Because stateless people are technically not citizens of any country, they are often denied basic rights and access to employment, housing, education, and health care. They may not be able to own property, open a bank account, get married legally, or register the birth of a child. Some face long periods of detention, because they cannot prove who they are or where they come from.

State succession carries a risk that some people will be excluded from citizenship if these issues are not considered early on in the process of separation. The world welcomed the birth of South Sudan in July, but it remains to be seen how new citizenship laws in both the north and south will be implemented.

"The dissolution of states, formation of new states, transfer of territories and redrawing of boundaries were major causes of statelessness over the past two decades. Unless new laws were carefully drafted, many people were left out," said Mark Manly, head of the statelessness unit at UNHCR.

In the 1990s the break-up of the Soviet Union, the Yugoslav federation and Czechoslovakia left hundreds of thousands of people in Eastern Europe and Central Asia stateless. While most cases have been resolved in these regions, tens of thousands remain stateless or at risk of statelessness.

An unfortunate consequence of statelessness is that it can be self-perpetuating. In most cases where the parents are stateless, their children are stateless from the moment they are born. Without a nationality, it is extremely difficult for children to get a formal education or other basic services.

Discrimination against women compounds the problem. UNHCR analysis reveals that at least 30 countries maintain citizenship laws that discriminate against women. And in some countries, women run a risk of becoming stateless if they marry foreigners. Many states also do not allow a mother to pass her nationality on to her children.

But, there is a growing trend for states to take action to remedy gender inequality in citizenship laws. Egypt, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Kenya and Tunisia have all in recent years amended their laws to grant women the same rights as men to retain their nationality and pass it on to their children. Changing gender discriminatory citizenship laws is a UNHCR goal this year.

An underlying theme of most stateless situations is ethnic and racial discrimination that leads to exclusion, where political will is often lacking to resolve the problem. Groups excluded from citizenship since states gained independence or were established include the Muslim Rohingya of Myanmar, some hill tribes in Thailand and the Bidoon in the Persian Gulf States. In Europe, thousands of Roma continue to be stateless in various countries.

Meanwhile, Croatia, the Philippines, Turkmenistan and Panama have all decided in recent months to become party to one or both of the international treaties on statelessness. Yet the issue remains a low priority in many countries due to political sensitivities.

The number of states party to the 1961 Convention and the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons is low. As of today, only 66 states are parties to the 1954 Convention, which defines who is considered to be a stateless person and establishes minimum standards of treatment. Only 38 are parties to the 1961 Convention, which provides principles and a legal framework to help states prevent statelessness.

"After 50 years, these Conventions have attracted only a small number of states,'' said High Commissioner Guterres. "It's shameful that millions of people are living without a nationality - a fundamental human right. The scope of the problem and the dire effects it has on those concerned goes almost unnoticed. We must change that. Governments must act to reduce the overall numbers of stateless."