Refugee students aim higher in pursuit of academic dreams

Refugee students aim higher in pursuit of academic dreams

Students in Kakuma Refugee Camp

Diing Manyang in Kakuma Refugee Camp

Diing Manyang, a young South Sudanese refugee, has a passion for advocating for education for refugees.

After finishing high school, Diing taught younger students at Kakuma Refugee Secondary School in the Kakuma refugee camp in northern Kenya. Refugees here have fled war in South Sudan since the early 1990s. What was meant to be a temporary refuge is now home to more than 170,000 people, and for many living in the camp, accessing higher education as young refugee students seems unobtainable.

“After high school, there aren’t a lot of options for education for refugees to pursue,” Diing says. “There are challenges like English language access, which can affect your ability to get higher test scores or fill out applications.”

Diing overcame these barriers herself with the help of an education program based in Rwanda that started recruiting students from Kakuma. She earned a scholarship from George Washington University in Washington, DC and, a couple of years later, earned a degree in systems engineering.

The program that helped Diing strengthen her college application and earn a scholarship stopped, however, accepting students from Kakuma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Suddenly, her passion grew an even sharper focus: increase refugees’ access to higher education and help others achieve what she has.

Talent is everywhere, but access and opportunity is not

Higher education – which, in the United States, includes universities, community colleges and trade schools – is a tool to unlock life-changing opportunities, self-reliance and overall safety and security for individuals that have access to it. And for refugee students like Diing, access to higher education can also mean safety, longer-term security and the opportunity to build a new life.

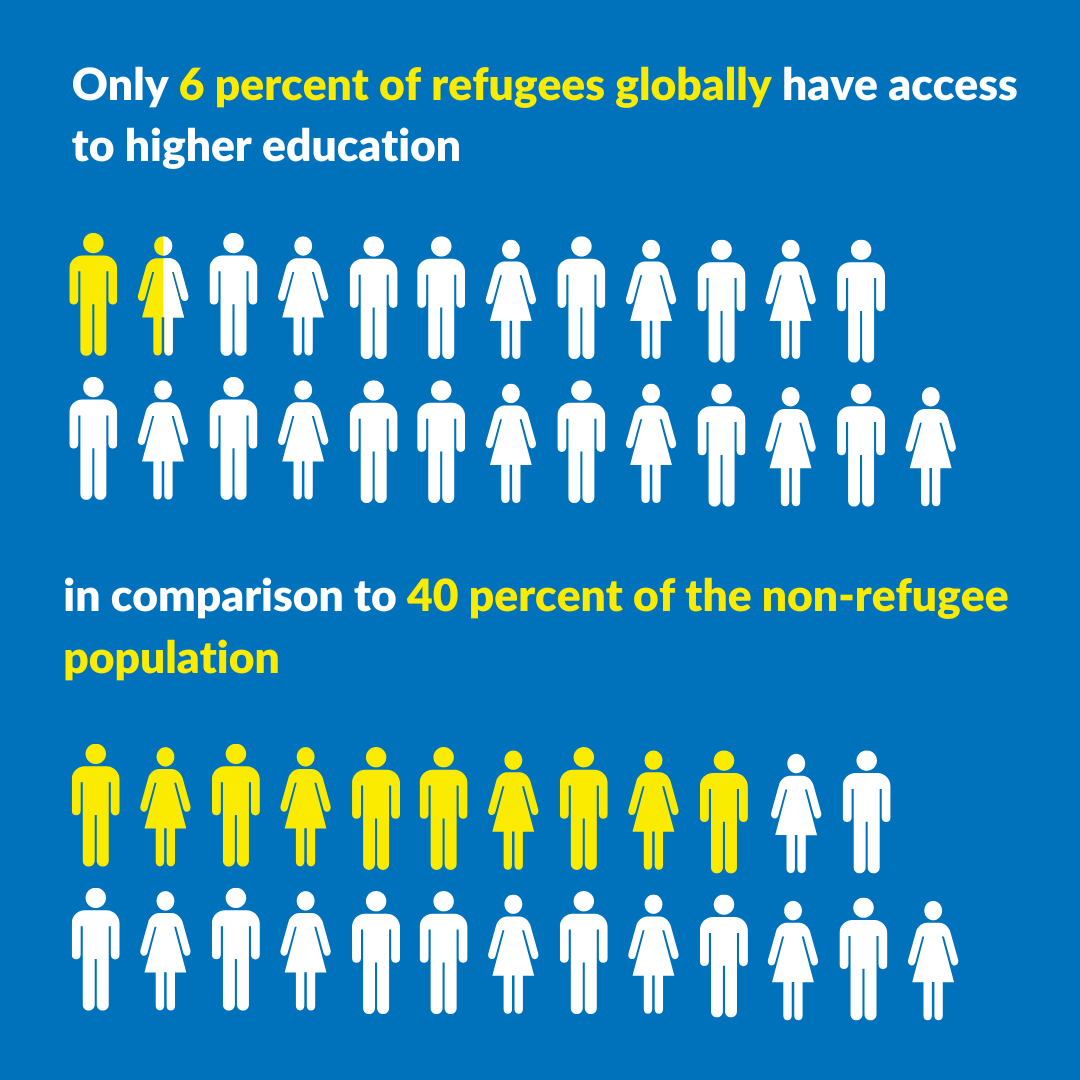

For many refugees such as those in Kakuma, higher education is all too often out of reach. Only 6% of refugees worldwide have access – in stark contrast to 40% among the rest of the population, according to UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency. Last month, governments, companies, universities, refugees and civil society organizations came together at the Global Refugee Forum to pledge to expand higher education access for refugees, with a goal of reaching 15% by 2030. People, institutions, and countries are already stepping up to fulfill this pledge.

Helping to unlock access to higher education for others

Diing Manyang co-founded Elimisha Kakuma, “Educate Kakuma” in Swahili, a program that helps refugees in Kakuma with college counseling, including English language skills, how to apply for university and financial assistance, mentoring and academic support. Many students go on to attend universities in the United States. She and her other co-founders – Dudi Miabok, who grew up in Kakuma and helped build Elimisha Kakuma’s on-site center, and UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador Mary Maker – have been educating refugee students for the past three years.

It’s not a lack of capability or want from refugees, but a lack of opportunity and knowledge of the complex college application process.

“We wanted to ensure a larger number of students had the opportunities we had, instead of stopping with us,” Diing says. Along with her cofounders, Diing draws on their lived experiences overcoming barriers to higher education. For example, Elimisha Kakuma understands that refugees, who have fled violence, war and persecution, may not have all of their academic records. For some students, their high schools have been destroyed during conflict. Not having travel documents is often a barrier or delay for students, including those who secure scholarships. Completing English exams, often required of foreign-born students by U.S. universities, can also be a barrier for refugees due to the cost and access to testing sites.

Teachers, mentors and counselors from Elimisha Kakuma help refugee students find solutions. They help universities understand why potential students may not have every required document. They offer alternatives, such as the widely recognized Duolingo online exam for English comprehension certification.

Elimisha Kakuma students have gone on to the University of California at Berkeley, Dartmouth College and Elmhurst University, among others. They prove it’s not a lack of capability or want from refugees, but a lack of opportunity and knowledge of complex processes that prevent access to higher education.

Elimisha Kakuma also supports refugee students after they’ve made it to campus.

“Without having that one person or student organization to help, it can become extremely hard and lonely,” Diing says.

From Kakuma refugee camp to university campuses across the globe

On U.S. campuses, the success of refugee students relies as much, or even more, on the commitment of higher education institutions.

Arizona State University offers best practices in accepting, supporting and promoting refugee students. Troy Campbell, Associate Director for the Advancement of Student Initiatives, says the university’s commitment is right in its charter. The institution is “measured not by whom it excludes, but by whom it includes and how they succeed.”

The university’s Education for Humanity initiative works with partners around the world to combine digital learning and higher education programs for refugees. An English language program provides lessons on campus and in places such as Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan. University departments also collaborate with community organizations that have the right resources and know-how to provide care to refugees, such as stress counseling and mental health support.

Day to day, Campbell answers questions about finances, helps students understand the travel documents they need to arrive for their first semester, helps with address changes as they secure housing and connects students with dental services. As he sees it, he helps with “anything that can cause stress” for refugee students, as these are important elements of success for refugee students in their personal, academic and then professional lives.

Higher education offers potential and power, especially for students who’ve been forced to flee their homes. People like Diing Manyang, organizations like Elimisha Kakuma and institutions like Arizona State University know this well and are working to transform the lives of more refugees.

“We’re not just impacting current generations, we’re impacting generations to come and the past ones too,” Campbell says.