After the horrors, Rwandans learn to live together again

After the horrors, Rwandans learn to live together again

KIGALI, Rwanda (UNHCR) - Emma's words pour out in a torrent in a land of silence and reserve where everyone tries not to remember. She wants to tell about those terrible 100 days in 1994 that devastated her life and the lives of millions of Rwandans.

As the director of Kigali's Remera orphanage, Emma was living with her 36 wards in the Rwandan capital when the violence broke out in April 1994. "During the night there was terrible fighting and the orphanage was hit," she says, recalling the fear and horror. "We had three cars, and at dawn we all left in them: the children, Father Vito and myself."

They fled to Nyanza, 90 km south of Kigali, but not without incident. Weaving through masses of people fleeing the rampage, they were stopped at the first road block.

"They made the three Tutsi boys get out," Emma recounts grimly. "Two of them were taken away. Father Vito intervened, but the armed men threatened him. Then they called two boys of about 11 or 12 years of age who were there at the road block, and ordered them to kill Bernard. Terrified, he asked me and Father Vito for help, but no one could do anything to save him. All the children witnessed the execution of their 16-year-old friend by other children."

The 100-day slaughter in Rwanda, which started shortly after President Juvenal Habyarimana died in a plane crash on April 6, 1994, took place everywhere and in every possible way - in the streets, hospitals, churches and schools.

Ten years later, the terrified faces of the corpses, their mutilated bodies trying to defend themselves from the machete blows, are still exhibited in memorials all over the country. In the churches of Nyamata, 20 km south of Kigali, people continue to wash the bones discovered a few days ago in the most recent mass grave.

"In April 1994, thousands of people sought refuge in this church," says Ruema Epimaque, guardian of the memorial at Nyamata. "The people felt safe here. This church had never been violated by weapons. The people fleeing the massacres of '59, '63, '73 and '92 had been spared." But the sanctuary was violated when the Interahamwe attacked on April 10, killing 10,000 people hiding in the church and the priest's house within five days.

The genocide killed an estimated 800,000 Rwandans and sent more than 2 million Rwandans fleeing into neighbouring countries, mainly Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC) and Tanzania. What followed has been defined by many as "the worst humanitarian crisis in the history of the United Nations".

In July 1994, cholera and other diseases broke out in the volcanic area where Zaire's camps were located, killing tens of thousands of Rwandan refugees.

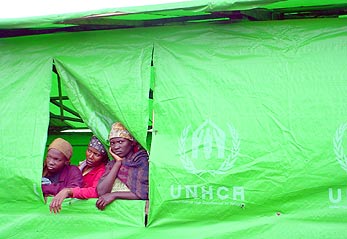

UNHCR struggled to assist refugees in camps alternately attacked and controlled by armed elements.

On April 7 this year, Rwanda and UN staff around the world solemnly marked the International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda, in order to remember the victims of the genocide.

UNHCR started promoting returns to Rwanda at the end of 2002, and helped more than 22,000 to repatriate last year.

These include civilians who have been hiding for years in the boundless territory of the DRC, former fighters with their families, and even child soldiers who were born and bred in exile. Refugees are also returning from Uganda and other African countries like Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe - with which UNHCR has signed agreements for the voluntary return home of the 60,000 Rwandans still living outside their homeland.

So far this year, more than 2,000 people have returned from Uganda with UNHCR assistance. Another 2,300 have passed through the transit centre of Nkamira in northern Rwanda, on the DRC border. Returning refugees receive food and relief items and are transported to their home areas within two days. Former fighters are sent to the Mutobo demobilisation centre, where they must follow the programme for reintegration into civil life. For two months they study 53 subjects, including Rwandan history, genocide and its impact on the region, the gacaca tribunals (traditional village courts), and national reconciliation.

In recent years the focus of the Rwandan government has been on reconciliation. It is taught in schools, in training courses for public officials, and in returnee villages. The gacaca tribunals are not just a judicial tool, they are also a reconciliation measure to help the victims express themselves, and to encourage dialogue between bring them and the perpetrators of crime.

Ethnic distinctions have been banned by official documents, while the government is focusing on promoting the concept of "Banyaruanda", the Rwandan people.

"It is difficult to say whether the present co-existence is true reconciliation or a way to get over the trauma," says Kalunga Lutato, UNHCR Representative in Rwanda. "What is certain is that the government has made reconciliation one of its priority objectives and its policies are based on national unity."

Madlene Mukashutene, who has just returned to Rwanda with her three children, is the only woman at the Mutobo demobilisation centre. As a former corporal in the Rwandan Armed Forces, she fled the 1994 genocide to Goma in eastern Zaire, moving deeper into the country when the camps were attacked two years later.

"What happened in Rwanda should not happen to any country," she says. "Today we have no choice: we have to learn to live together in order to arrive at being a unified people."

In front of the Nyamata church, someone has written: "If you had known yourself, if you had known me, you wouldn't have killed me." It is a cry of sorrow for what could have been avoided, and a warning not to be forgotten in the Rwanda of reconciliation.

By Laura Boldrini in Kigali, Rwanda