Imagining Syria

Over the past 11 years of conflict and instability, almost 5.7 million Syrians have found safety in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt, with most seeing little prospect of a return home any time soon. Nearly half are children, according to UNHCR data, while a third are aged 11 or younger and have never known their country at peace.

Despite this, many of these children still feel a deep connection to their unfamiliar homeland, and cling to the hope of one day returning in safety. They carry a picture of Syria in their minds, based on stories shared by parents, brief phone conversations with relatives who stayed behind, or images from family photos and news reports.

To find out how this separated generation imagines a country that remains largely unknown yet continues to define many aspects of their lives, UNHCR invited young Syrians across the region to draw their images of home and describe the results.

Under the supervision of teachers and trained counsellors, who regularly use art as a form of self-expression and reflection, the children were able to share their feelings about their home country and reveal their hopes for the future of Syria.

Jordan

Ahmed, 8, was born the day after his parents fled their home in Daraa in southern Syria, just a few kilometres away across the border in Jordan. His mother tells him his birth was a sign of hope for the future they were going to build.

Ahmed imagines Syria as a place “full of rainbows”. “I mean that after the rain, when the sun comes, there will be rainbows,” he explains. “Syria is a beautiful country – the most beautiful country, because it is our country.”

Ahmed, 8, who was born in Jordan in 2013, holds up his picture of rainbows over Syria.

When asked to draw what she thinks Syria looks like, Sajida, 8, pauses. “But Syria is destroyed,” she says. Images of war and destruction have dominated news reports from Syria for the past 11 years, and many children struggle to imagine anything else.

Instead, Sajida focuses on drawing what she hopes Syria will look like one day. “This will be my house. It’s pink because that’s my favorite color. Also, my uncles house in Syria used to be pink. The sea will be next to our house. We can go swimming every day and there will always be sunshine.”

'But Syria is destroyed' Sajida, 8, replies when asked to imagine her homeland. Instead she draws what she hopes the future will look like.

Lebanon

Deteriorating economies in many of the countries hosting Syrians have had a devastating effect on refugee children. In Lebanon, where nine out of ten refugees are living in extreme poverty, an increasing number of children face food insecurity and are being married off or dropping out of school to support their families.

Originally from Deir Ezzor, 11-year-old Ali vaguely remembers riding in the car as his father delivered vegetables and the toy cars he used to play with back in Syria, which he left with his family in 2016.

Ali, 11, works in an auto body shop on the outskirts of Beirut to help support his family, but longs to return home.

In Lebanon, he supports his family by working in an auto body shop in the outskirts of Beirut, helping to paint customers’ vehicles. “Here there are no toys,” Ali says. “I don’t do anything here, I just work in the shop.” He longs to go back to Syria, he adds, to see the olive and apples trees he still remembers from early childhood.

Now aged 11, Omar was just a baby when his parents left Syria, but their stories and details shared by relatives who remained have kept alive his connection to the country. His drawing reflects the dual identity that growing up as a refugee in Lebanon has given him, with the Syrian flag on one side and the Lebanese flag with its green cedar tree on the other. “I love Syria and I love Lebanon too. I had some good times here,” Omar explains. “This is why I divided the paper.”

Omar, 11, shows his drawing of the Lebanese and Syrian flags at a youth centre in Beirut, Lebanon.

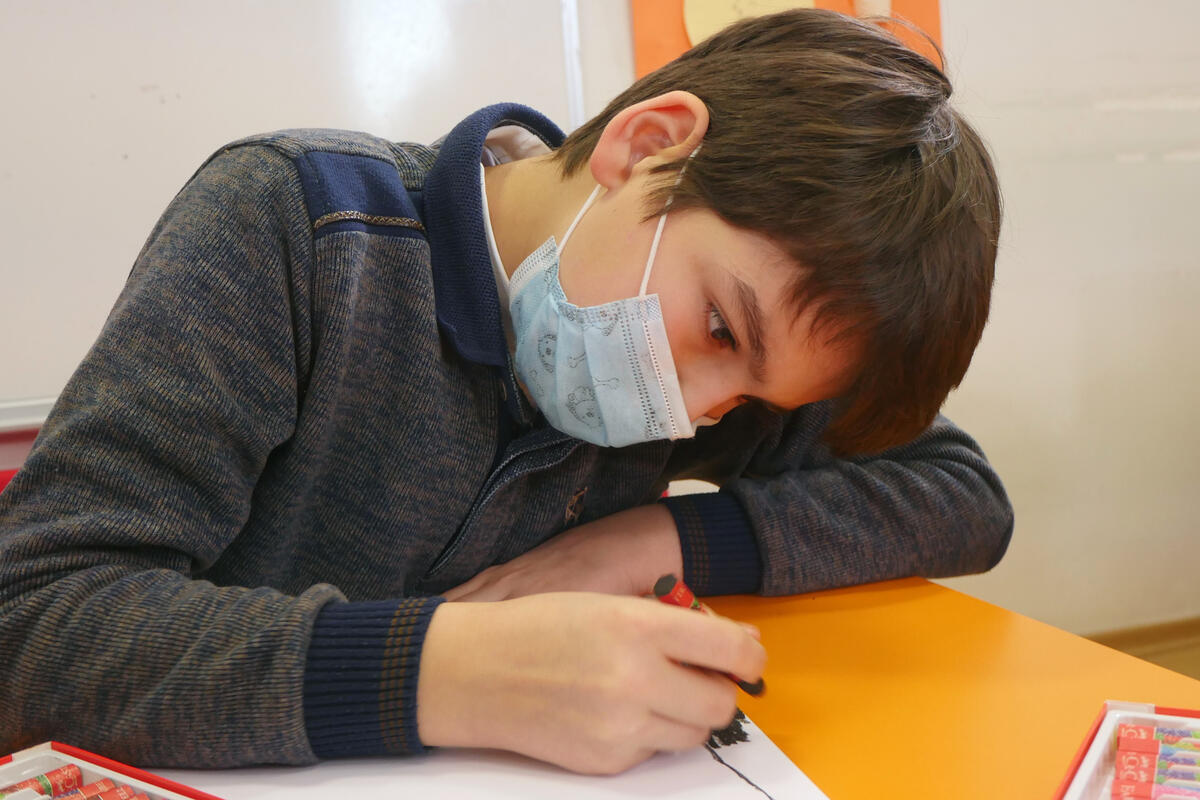

Türkiye

Yousef, 11, was born in Aleppo and came to Turkey with his family in 2015. He says he has no memory of Syria, and one of images he draws reflects reports of conflict and destruction he has grown up hearing. Flaming tanks fire their weapons, and a figure lies prone on a black asphalt road.

“When they say Syria, what comes to my mind is things like tanks that I have seen in war movies,” Yousef says. A second picture shows a bright rainbow collage, which Yousef says represents the future. A psychologist present says the images reveal that despite Yousef’s awareness of events back home, he retains a sense of resilience and hope.

Yousef's drawing of tanks and prone figures reflects the reports of conflict in Syria he has grown up hearing.

Iraq

Dilkhaz, 11, has lived with his parents in Domiz-1 refugee camp in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq since they fled Derik in Syria in 2015. “I go to school, in fourth grade,” he says. “I am a good student. I want to become a doctor in Syria, among my people and relatives, treat patients and take care of poor people.”

He has drawn a landscape of rolling hills dotted with trees under blue skies. “I have painted the beautiful Syria. There are trees, water, clouds,” Dilkhaz explains. “Syria is good place where my grandfather owns a big house, sheep, and hens. There are many villages and green landscapes there.”

Dilkhaz, 11, who lives in a refugee camp in northern Iraq, imagines Syria as a beautiful landscape of rolling hills and trees.

Egypt

Issam, 11, was born in the Jobar neighbourhood of Damascus, but fled with his family to Egypt as a young child. He has vague memories of the busy local marketplace, queueing with his father to buy bread and meat. The image of Syria he draws, however, was born of his grandmother’s tales of the cherry tree in the garden to their family home.

“She told me that in the past, my father would go on the roof … to pick the cherries and would give some to all our relatives,” Issam says. “They had their own garden, and my cousins would play in it. My grandmother told me these stories, I don’t remember them.”

Reporting by Lilly Carlisle in Jordan, Paula Barrachina in Lebanon, Cansin Argun in Türkiye, Rasheed Hussein Rasheed in Iraq, and Radwa Sharaf in Egypt.