UNHCR urges more support for statelessness treaty on 50th anniversary

UNHCR urges more support for statelessness treaty on 50th anniversary

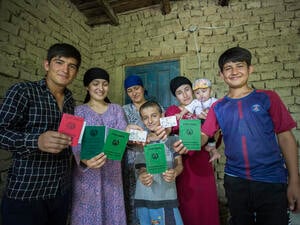

Thanks to policy and law reform in Sri Lanka, these young "hill Tamils" have broken the cycle of statelessness faced by their ancestors who were brought from India to work on tea estates nearly 200 years ago.

GENEVA, August 30 (UNHCR) - The UN refugee agency has reiterated its call for governments to sign on to two international treaties on statelessness, an important step towards ending the legal limbo faced by millions of people without a nationality.

The call to action comes on the 50th anniversary of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness on Tuesday. Together with the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, it provides a legal framework to prevent statelessness from occuring and to protect people who are already stateless.

UNHCR estimates there are up to 12 million stateless people in the world. With no nationality or status, they are often denied basic rights and access to education, health care, housing and employment.

While the problem is huge and affects many countries, governments have so far shown too little commitment to resolve it. Of the 193 UN member states, just 38 have acceded to the 1961 Convention while only 66 are parties to the 1954 Convention.

"Everyone should have a nationality: It is a fundamental right," said UNHCR spokesman Adrian Edwards at a news briefing in Geneva on Tuesday. "Millions of people around the world continue to suffer the consequences of not having a nationality. And in an age of increasing labour mobility, for many people, children in particular, the risks of losing one's nationality are growing."

Fifty years after the 1961 Convention was adopted, the factors driving it have not changed. In a recently published historical overview of the 1961 Convention, Oxford University professor Guy S. Goodwin-Gill noted that when the UN's International Law Commission first convened in 1952 to develop a treaty to prevent and reduce statelessness, "Statelessness was seen as 'undesirable' from the perspective of orderly international relations, for every individual should be 'attributed to some State'; and it was also undesirable for the individual, because of its 'precariousness'."

These are the same arguments for states to accede to both statelessness conventions today: set minimum global standards, help resolve conflict of law issues and prevent people from falling through gaps between citizenship laws. It is a known fact that preventing statelessness and protecting stateless people can contribute to international peace and security and prevent forced displacement. Resolving statelessness can also promote the rule of law and help better regulate international migration. It is therefore in the interests of states to become party to the two conventions.

In recent months, Croatia, Panama, the Philippines and Turkmenistan have made the decision to become party to one or both of the statelessness conventions.

"We expect that a number of states will either accede to one or both of the statelessness conventions this year or pledge to do so at a ministerial-level meeting of UN member states being held in Geneva in December," said Edwards. "Nonetheless we are today repeating our call to governments, advocates, media, and individuals for a redoubling of efforts so that more states sign on to the statelessness conventions, reform nationality laws, and resolve the problem."