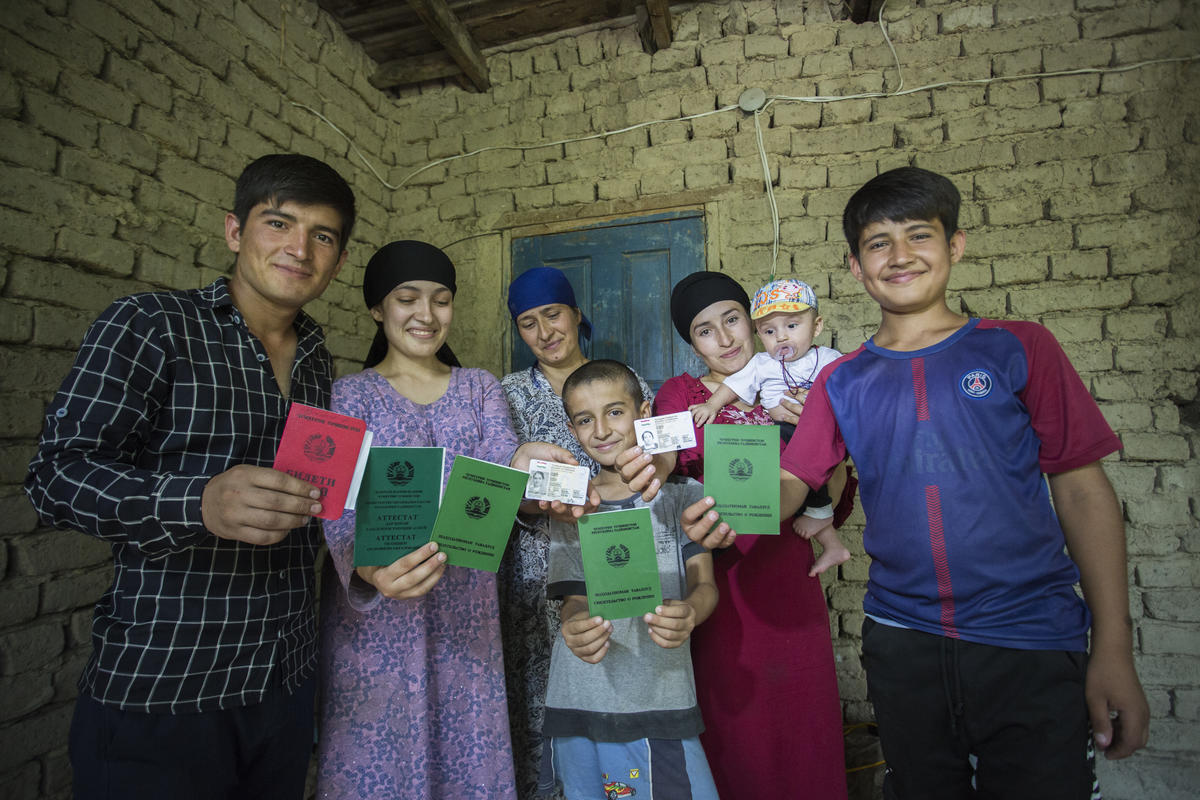

For stateless people, there is no alternative to winning this fight

For stateless people, there is no alternative to winning this fight

Nepali lawyer and activist Neha Gurung attends the Global Summit on Gender Equality in Nationality Laws in Geneva, Switzerland, on 14 June.

Raised by their single mother Deepti Gurung in Lalitpur near Kathmandu, Neha Gurung and her sister grew up stateless due to Nepal being among 24 countries worldwide that still do not allow women to pass their nationality to their children on an equal basis to men. Together, Neha and her mother fought a long legal battle in the country’s Supreme Court before she and her sister finally gained citizenship in 2017.

After graduating law school, Neha joined the Forum for Women, Law and Development (FWLD) – a Nepali NGO that campaigns on statelessness and citizenship issues and which was instrumental in her own case. She and her mother also established their own NGO, and Neha recently became co-lead of the Global Movement on Statelessness.

On 13 June in Geneva, Neha attended the Global Summit on Gender Equality in Nationality Laws, convened by the Global Campaign for Equal Nationality Rights, UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, UNICEF, and UN Women. The Summit aimed to encourage reforms in countries with gender-discriminatory nationality laws, which result in wide-ranging human rights violations and harm to affected women, their families and society.

Here, Neha describes her own experience of statelessness, her legal battle to gain citizenship and her global advocacy on behalf of stateless people.

My younger sister and I were raised by a single mother, but we did not feel the lack of a father. She made our childhood very happy and fulfilling. In grade 10 you have to sit a national level examination and fill out a form. There was no space for the mother’s name, only the father's name. I was confused so I asked my teacher, and she said: “Don't you know your father's name?” I said no, and she replied loudly: “What kind of a child does not know their father's name?” And even though it was a normal question for her because she comes from a society where that is what people think a normal family is, for me it was extremely difficult to hear those words. I realized then that life would not be easy, because even though we didn't feel any different, people and society viewed us differently.

By grade 12 I wanted to study medicine, but my mother knew that would require a citizenship certificate. She had been going to ward offices, central government offices, speaking to people, but everywhere she was denied and humiliated and told things like: “Why don't you just marry off your daughter to a Nepali guy, then maybe she can get citizenship?” That was when I realized it was a huge thing, that without a citizenship certificate I would not even be allowed to study. She met a lot of NGOs, advocates, lawyers, and whenever I could, I always accompanied her. Eventually, we stumbled upon the Forum for Women, Law and Development (FWLD), which is the most influential NGO in terms of statelessness and citizenship in Nepal. There was a lawyer there called Meera Dhungana, who said we should file a Supreme Court petition. She told us our case was winnable and she really showed us hope, so that was when our legal battle started.

There's a lot of work to be done to change society and create awareness.

Meera knew about my situation and that I was not able to study. She told me: “I can't do anything about wanting to study medicine, but I'm a lawyer and I know everybody in the legal field. If you want to choose the black coat of a lawyer instead of the white coat of a doctor, then I can help you.” When I was at law school, BBC Nepal hosted an event on the issue of citizenship. The guest speaker was a politician who was extremely negative on the issue of gender and equal citizenship rights. The audience was allowed to ask questions, so I raised my hand and said: “Sir, my father is the one who left us and who did not take any responsibility, but my mother took all the responsibility and raised us as good citizens, and now the country is not providing us citizenship. I'm denied all my rights and feel like a prisoner inside my own country, so can you please tell me what I have done wrong?” He casually replied: “Oh, daughter, it's not your fault. It's your mother's fault because she should have known better how to keep her husband.” I didn't know how to respond. I just sat there. But the anger and inability to understand why people and society succumb to these kinds of ideas has always been with me. There's a lot of work to be done to change society and create awareness.

Neha and her mother Deepti Gurung, who together fought a long legal battle to secure Neha's citizenship, pictured together in Geneva, Switzerland.

In Nepal, an amended Citizenship Act was recently approved by the President. But a petition has been filed against the approved act, so the Supreme Court has halted implementation for now. One of the petitioners is the same politician who gave me that answer at the BBC event. I'm optimistic that the act will pass, (but) it still has very discriminatory provisions because the constitution itself is discriminatory. It discriminates against women and puts them into three categories – a woman with a Nepali husband, a woman with a foreign husband and a woman with an unidentified husband. For men there’s nothing like that. But at least the act will provide citizenship to a lot of people, and they can open bank accounts, have a driving license, study abroad, travel or do work. Then we will have to continue our advocacy for wider constitutional change, and that battle is ongoing.

I can't just close my eyes to the injustices.

On the day I finally got my citizenship, it felt surreal. I was in my fourth year of law school and had a big exam that day, so I went to college and my mother went to the Supreme Court. She called me right after my exam, crying, and said we had a positive decision and that I would get citizenship. I hung up the phone, but I couldn't tell any of my friends because I knew that nobody would really understand. People say that pain and hardship make you stronger, but it's not the pain or hardships that make us stronger, it's the people who are there to support us through those hardships. I finished my studies in 2019 and I took my bar exam in 2021. My first job was with FWLD, the organization that helped with my case. There are some things that once you see them, you can't unsee. I can’t just close my eyes to the injustices and difficulties that people are facing. As an activist, I've been through it, and I know how it feels to live that life. I'm in a very happy place and I think that I can use my voice and my experiences to support others.

My mother and I established the Citizenship Affected People's Network in Nepal, and since March I’ve been engaged with the Global Movement on Statelessness as a co-lead. Being a part of that global movement showed me the importance of people working at the grassroots level, of stateless people and stateless activists. Progress is not possible unless and until our voices are heard. In many countries, the issue of citizenship and nationality is highly politicized, and it's not seen through a human rights lens. Acknowledging the citizenship rights of people would bring huge benefits, not only to those individuals but also to the countries where they live, because people will be able to study, build careers and ultimately benefit society and the economy. I'm optimistic that there is going to be change, maybe not sudden, but gradual change. Like my mother always said about our own case, there is no alternative to winning this fight, and sooner or later we will win.

Everyone has the right to a nationality. Without nationality, stateless people cannot fully access their human rights and achieve sustainable development. UNHCR’s #IBelong campaign urges governments to close the legal and policy gaps that continue to leave millions of people without a nationality or allow children to be born stateless. The campaign is a call to action for each of us, to learn, share, and take action to end statelessness.