Dead end for displaced refugee youth in shanty on the edge of Bogotá

Dead end for displaced refugee youth in shanty on the edge of Bogotá

SOACHA, Colombia, August 30 (UNHCR) - Over the years, the suburb of Soacha has crept haphazardly and unregulated up the hills south of Bogotá as thousands of families flocked to the Colombian capital to escape violence in rural areas.

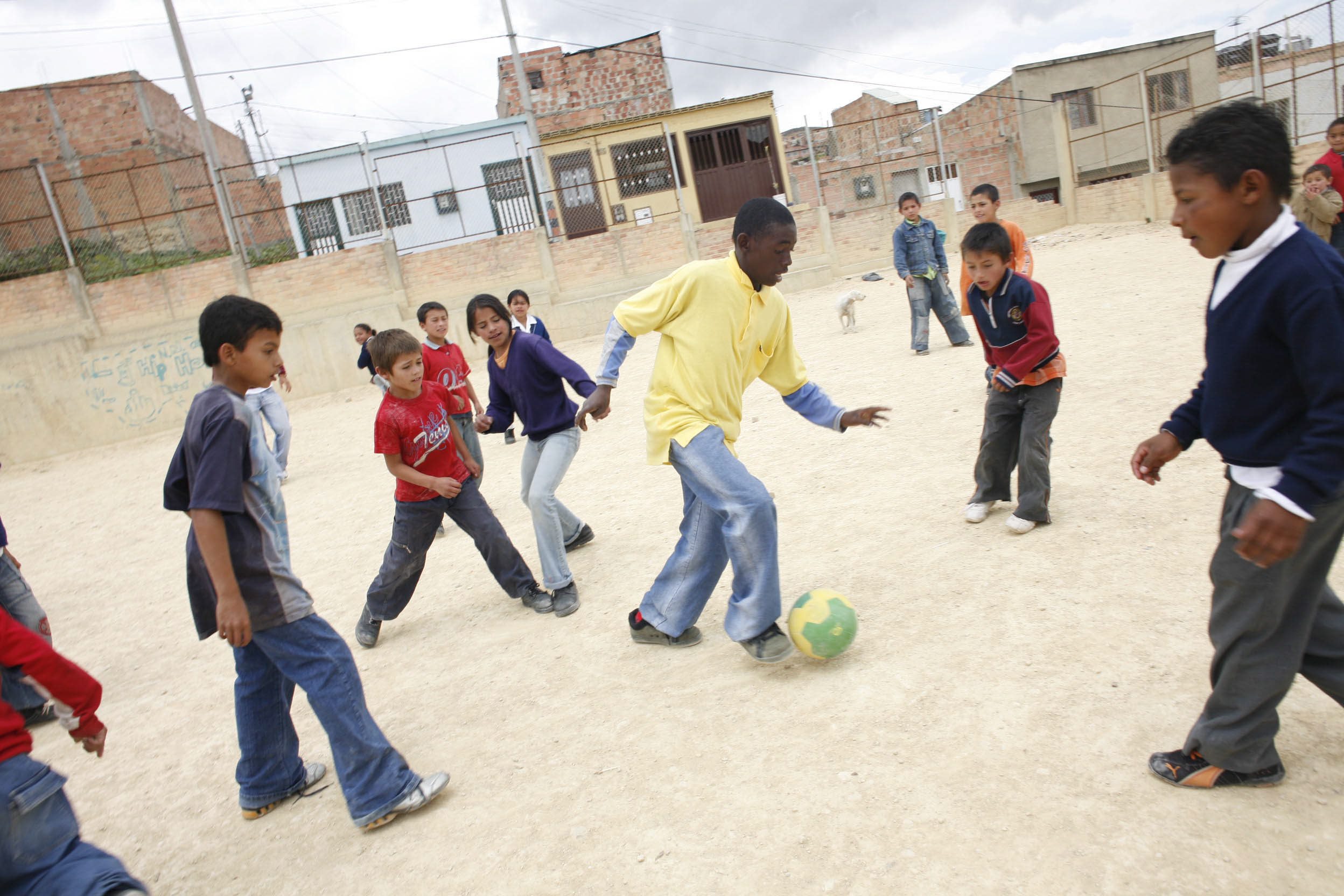

They feel relatively safe in the warren of crude brick and corrugated iron homes and shops that make Soacha's Altos de Cazuca neighbourhood seem like a giant human anthill. But for many of their children, the sprawling urban zone of more than 450,000 people, including almost 32,000 registered internally displaced people, or IDPs, is a cultural, social, educational and careers dead end.

While their parents might dream of returning to farms or villages, the young have caught the city bug. "When we speak to the families, the adults say they want to return to their home regions, but the young want to stay here or in Bogotá," said a UNHCR staffer who works in Soacha.

For various reasons, especially discrimination and stigmatization as well as poverty, the shanty town offers them little future. Indeed, the only way out for some is to join criminal or irregular armed groups that, aid workers and locals say, still hold sway over parts of Soacha - especially at night.

UNHCR, which began working in Soacha in 2005, believes the young need help and direction. "These young people have no prospects for the future because the efforts at the local level so far have been insufficient," noted Terry Morel, UNHCR's representative in Colombia, adding: "We worked on finding solutions which allow people to construct a future,"

The refugee agency coordinates humanitarian action and supports organizations such as La Casa de los Derechos (House of Rights) and Learning Circles, which work to protect displaced families and their young by easing access to education, health care and shelter, all of which they are entitled to.

Juan, who was playing drums at a youth centre when UNHCR caught up with him, gave some insight into the hurdles that the displaced youth of Soacha face. The 17-year-old fled to Altos de Cazuca a year ago from the northern city of Cucuta after his mother got into trouble. "My mother said I had to leave, otherwise I would be killed because of what she had done," he said, without elaborating.

Juan was lucky. He made a friend on arrival in Soacha who lent him money and he found a job selling cheap jewellery. But like so many other new arrivals, he encountered hostility from the locals. "They don't welcome displaced people. When you walk along the street, they look at you in a bad way and they talk to you in a bad way. When you go and ask for a job, the first thing they ask you is if you are displaced," he explained. "The young people here don't have that many opportunities for jobs," the UNHCR staff member in Soacha confirmed.

Juan was also unable to pursue his goal of studying because, like many displaced people, he lacked money. But others have been barred from local schools on discriminatory grounds. UNHCR staff say discrimination and stigmatization of displaced people are worrying developments.

The young face other serious obstacles to their personal development and improvement. Perhaps the most insidious is the influence that irregular armed groups exert in the shanties of Soacha, so close to the centre of Bogotá.

Forced recruitment is a danger, but the offer of money is also a lure to young people with nothing else. The social policies of these groups also affect the young. "You will have threats against people who are taking drugs, who are sex workers, who maybe have HIV. They will be threatened and maybe even eliminated," Morel noted.

Such social control, including bans on certain types of music or dress and even dreadlocks, "sometimes leads to secondary displacement within Soacha," says an official of the House of Rights, which in 2008 launched a campaign with UNHCR to inform young people about what they could do if menaced by forced recruitment.

The official from the House of Rights, which promotes an institutional presence in Soacha, offers legal advice and stands up for the displaced, also said sexual and domestic violence against children, as well as parental neglect, were problems.

But while the outlook for young people in Soacha is grim, there are rays of hope. The very presence of UNHCR in an area where 500 homicides were recorded in the early 2000s is a step forward. "UNHCR went in there and we opened up a House of Rights and we support the presence of the institutions," Morel said, adding: "This is critical, because it means people don't feel abandoned."

And the young themselves are showing signs of independence and initiative. "The youth centre was created by young people," the House of Rights official revealed, while adding that some of them had taken part in workshops to study public policies and have a greater say in their future. And Juan certainly has a positive attitude. "I'm optimistic. The band is starting to plan for the future and I have a job."

By Leo Dobbs in Soacha, Colombia