Helping Crimean Tatars feel at home again

Helping Crimean Tatars feel at home again

KYIV, Ukraine, June 8 (UNHCR) - The Izetov family could rival any legislator, politician or lawyer in their knowledge of Ukraine's Citizenship Law and procedures, despite spending decades in forced exile and only returning to their ancestral homeland in recent years.

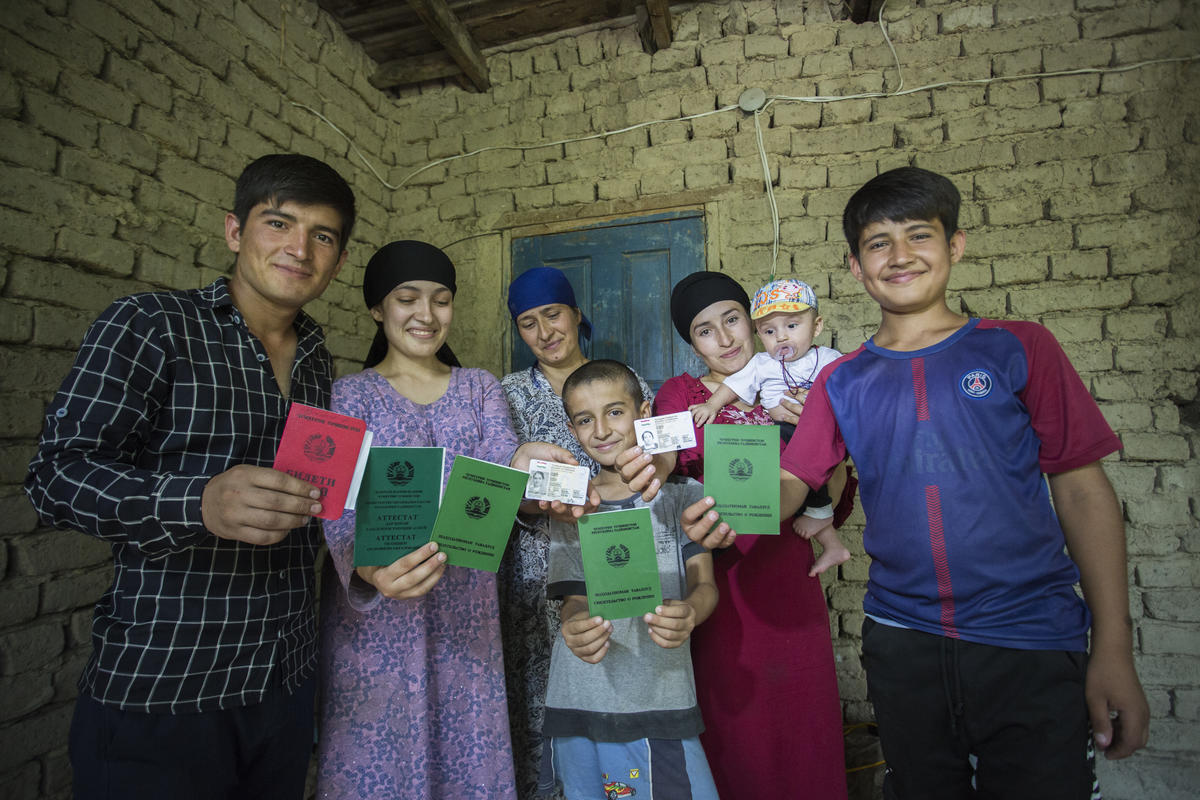

Their knowledge is first hand. "My mother-in-law was the first to return to Crimea in 1993," says Ulvie Izetov, referring to the peninsula in southern Ukraine where her Crimean Tatar ancestors originated. "She became a citizen in 2000. In 2002, my mother and my son came back. They applied for citizenship the same year, and received Ukrainian passports in 2003."

Ulvie herself became a naturalised Ukrainian this year, along with her husband and elder son. "We have to become citizens. We have not come for a spell, but to stay forever in our native land. Now I am confident of the future of my sons," she says, sure that her grandson, too, will receive a Ukrainian passport as soon as he grows up.

This certainty and sense of belonging is a welcome change after more than 60 years of living in limbo. The Izetovs were among more than 200,000 Crimean Tatars deported in May 1944 under Josef Stalin's regime, which accused them of siding with the Nazis. Some families were given as little as five or 10 minutes to pack their belongings and food before being crammed into cattle trains bound for republics that were then part of the Soviet Union. Many deportees died during the long and hard journey; most of the survivors ended up in Uzbekistan.

Although the deportation scheme - which involved eight entire ethnic "nations" in all - ended with Stalin's death in 1953, the Crimean Tatars were prevented from going back to their homeland, which occupied a strategic position in the Black Sea and had become a popular vacation and retirement spot for Soviet officials. Those deportees who tried to return to the peninsula were deported anew.

It was only with the weakening of Soviet central control in the late 1980s that the Crimean Tatars started streaming home steadily. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1989, many of these formerly deported people (FDPs) fell through the cracks as former republics became independent countries. Some became stateless while others now held citizenship in Uzbekistan or other former Soviet republics to which they had no real ties.

By 1996, close to 250,000 FDPs - primarily Tatars - had returned to the Crimean peninsula from deportation. Some 150,000 of them could obtain citizenship automatically under Ukraine's Citizenship Law of 1991, but more than 100,000 who returned after the country declared independence faced greater problems in obtaining Ukrainian citizenship. Some 28,000 of them became de facto stateless by returning after Ukraine's Citizenship Law but before the citizenship law of their country of deportation took effect.

Another 80,000 had already become affiliated with citizenship of their countries of deportation and now faced problems renouncing this citizenship and acquiring that of their new home, Ukraine. To qualify for Ukrainian citizenship, they had to renounce their Uzbek or other citizenship, an often long, bureaucratic and costly process. It could be years before a returning Crimean Tatar could start exercising his or her rights as a citizen.

UNHCR started working in Crimea in 1996 after the government requested help to reintegrate the returning Tatars. "At a volume of US$5.3 million, the assistance that UNHCR has provided over the last 10 years to the integration of FDPs and their descendants in Crimea constitutes the most comprehensive programme related to the prevention and reduction of statelessness that we have implemented in any one country to date," said Guy Ouellet, UNHCR's Regional Representative in Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova.

Initial assistance ranged from temporary shelter to infrastructure and development programmes for the returning FDPs in Crimea. UNHCR funded non-governmental organizations to develop a network of local lawyers to provide free legal aid to the returnees. The agency also supported the training of all authorities involved in the citizenship process, from local passport offices in Crimea to the Citizenship Directorate of the President. It extended legal advice to the parliament and government of Ukraine to adopt adequate national legislation and bilateral treaties to simplify the naturalisation process.

At the same time, UNHCR has launched several citizenship campaigns to sensitise the returnees to the advantages of Ukrainian citizenship. Without it, "they cannot work for government agencies. They cannot find a job as they are not accepted at job placement centres because they are citizens of Uzbekistan. Even if they do find work, most employers do not want to register them officially," explains Elvira Zeitullaeva, who manages the Assistance foundation, a key UNHCR partner in Crimea.

By end-2001, after the adoption of the new and greatly improved Ukrainian Citizenship Law and a bilateral agreement on simplified procedures for changing citizenship between Uzbekistan and Ukraine, more than 90 percent of the returning Crimean Tatars had become naturalised Ukrainian citizens. Problems resurfaced, however, when the Uzbek side rejected the extension of this agreement beyond end-2001.

More recently, due to further developments in Ukrainian law, the rate of naturalisation has risen sharply since late last year, with over 3,500 Crimean Tatars receiving citizenship since October 2004.

Among the changes is the Kyiv government's decision to denounce bilateral agreements on the prevention of dual citizenship with Uzbekistan and Georgia, which now allows Crimean Tatars returning from those countries to benefit from simplified procedures under the 2001 Citizenship Law. Benefits include a year of provisional citizenship while they renounce their previous citizenship, as well as a complete waiver of renunciation procedures if the cost - US$105 to renounce Uzbek citizenship, for example - exceeds the minimum monthly wage in Ukraine.

Seit-Yakhya Seit-Yakubov has been back in Ukraine since 2002. He obtained his citizenship with his wife and daughter in 2004. "It helped a lot that they implemented the simplified procedure with the cancellation of the Uzbek citizenship. We feel relieved that we are finally citizens of Ukraine," he says.

"From now on, we can take part in elections," adds Alim, his teenage grandson, who became a citizen this year and will benefit from free education, among other rights.

"Sometimes I count all this money that we spent on these procedures and could instead have used to buy bricks and window frames for our unfinished house," sighs Ulvie Izetov, who is nonetheless happy with her new status. "Without citizenship, we weren't able to register land for a very long time."

Land issues in Crimea are still critical for the returning Tatars. Many of them came back to find their ancestral land occupied by others, and have been appealing for restitution and possible compensation for lost property and rights.

"It is most important that a citizen has the right to obtain a land plot and start its privatization," stresses Zeitullaeva of the Assistance foundation.

Sergey Babashin, who heads the citizenship, immigration and registration department under the central directorate of Ukraine's Interior Ministry in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, sums up the challenges ahead: "The main thing is to inform people more - this is what matters. Now we have to live together, and the faster they integrate into society, the less inter-ethnic problems we will have."

According to the Assistance foundation, some 8,000 Crimean Tatars and their families who have returned from deportation remain foreign citizens, and between 1,000 and 2,000 more are coming back every year. Thanks to the simplified procedures, the naturalisation rate is outpacing the new arrivals, with passports being issued within weeks. This should free up the authorities and aid agencies to focus on longer-term integration to help the Crimean Tatars feel at home again.

Ukraine's very progressive citizenship legislation has allowed it to sign the 1997 European Convention on Nationality. Further amendments currently prepared in Parliament could soon lead to a ratification of this convention as well as accession to the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. On June 7, UNHCR and the Council of Europe convened a conference in Kyiv to discuss and promote this process as well as Ukraine's future accession to the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, with representatives of Ukraine's legislative and executive.

By Natalia Prokopchuk

UNHCR Ukraine