For Valentin, statelessness meant 'a lifetime proving I exist'

For Valentin, statelessness meant 'a lifetime proving I exist'

For his entire life, Valentin Rakip has felt like a foreigner in his own country. But after a 12-year legal struggle, all that is about to change – and he may even be on the path to achieving his dream of becoming a chef.

Until just a few days ago, Valentin, 20, from Skopje, the capital of North Macedonia, was one of millions of stateless people around the world. With no legal identity, he was never able to do things most of us take for granted, such as enrolling in high school, having a medical or dental check-up, getting legal employment, or traveling outside his country.

Despite being born in North Macedonia, “I feel like a foreigner in this country,” he said with obvious pain.

Valentin fell into this limbo because his mother, a Serbian national, did not register his birth or those of his three brothers and three sisters, and his father, a Macedonian citizen, did not acknowledge paternity. His mother deserted the family repeatedly during his childhood and left them and the country for good after his father died five years ago.

"I feel like a foreigner in this country."

That left Valentin and his siblings to fend for themselves in a ramshackle house in one of the poorest areas of the city, having only their friends and kindhearted people to rely on.

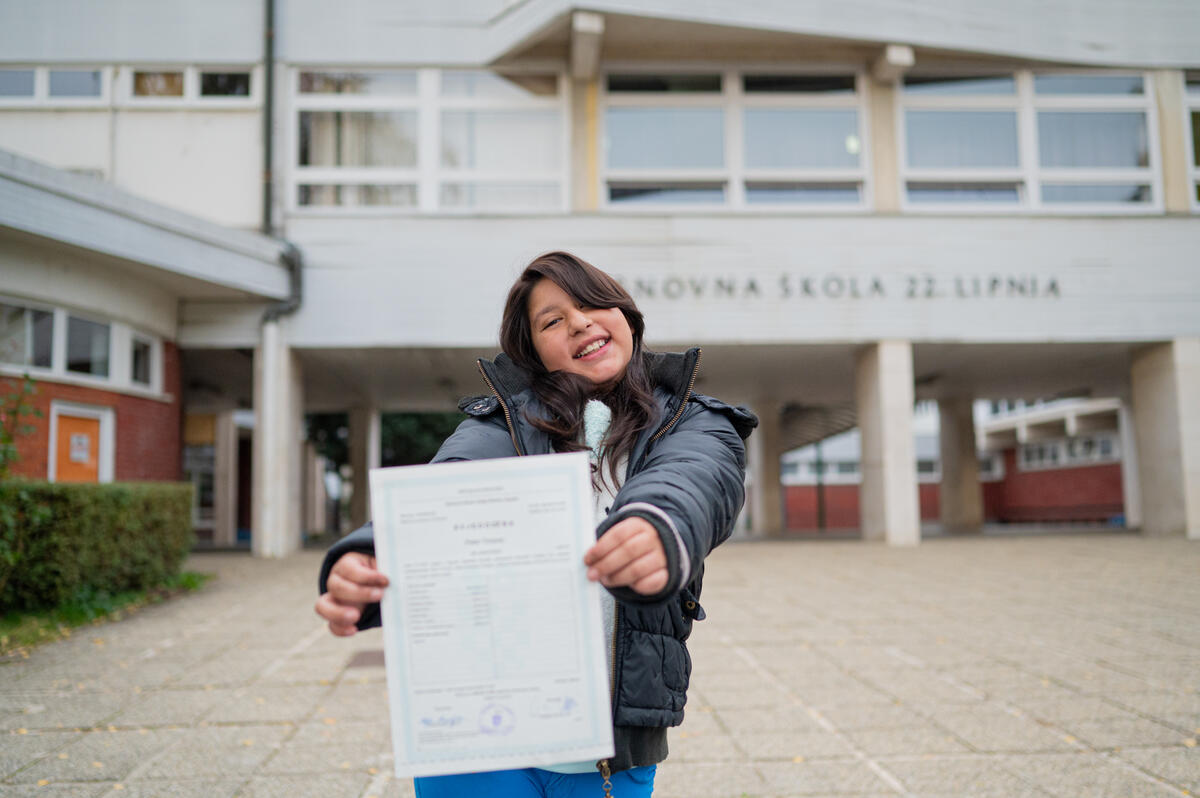

It has taken more than half his life, but thanks to UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, and a partner, the Macedonian Young Lawyers Association, Valentin has finally gained full citizenship and will soon receive his first national ID card. With free legal representation by a lawyer from the association, Valentin managed to register his birth in 2017 and at the end of last year, a court confirmed the paternity of his father, paving the way for Valentin to acquire nationality nine months later. Once Valentin receives an ID card, it will open the door to all the legal rights of a citizen.

In 2014, UNHCR launched the #iBelong campaign to end global statelessness within 10 years. The nature of the problem means it’s impossible to say precisely how many stateless people there are in the world, but in North Macedonia, UNHCR estimates there are at least 700 stateless people.

Some, like Valentin, do not have birth certificates because their births were not registered in time. Others became stateless when former Yugoslavia broke apart in 1991.

“It takes years of patient work to resolve statelessness,” said Monica Sandri, UNHCR Representative in North Macedonia, “and requires a coalition working towards this goal – the government, United Nations, private sector, media, academia, the whole society.

“As our goal is to help all the stateless people in this country acquire citizenship by 2024, we have to look ahead to what we want to achieve and map out all the steps we need to take to get there to make sure no one is left behind,” she added.

With this in mind, UNHCR's operation in North Macedonia is embracing an ambitious multi-year approach that focuses on solutions, such as helping Valentin and others in similar situations resolve their statelessness.

North Macedonia is one of 24 UNHCR country operations worldwide that are adopting a similar mid- to long-term approach, and by 2024, the entire organization will transition to this longer-range planning model.

Although the second youngest of seven siblings, Valentin was the glue that held the band of parentless children together. They also relied on life-saving support from a charity, the Daycare Centre for Street Children.

The charity looked after the children when the parents were absent, supplied them with food, and imparted meaningful lessons. “From them I learned confidence and culture,” said Valentin. “I learned everything from them, how to become a human being, how to work. If it wasn’t for them, I don’t know what I would be doing now.”

Deprived of the opportunity to go to high school, Valentin and his siblings have had to rely on informal work, such as selling clothes at an outdoor market. He was taken under the wing of a mentor at Association Public, sold a street magazine called Face to Face (Lice v Lice in Macedonian) and began to acquire skills to become employable.

"I see that I am good at whatever I try."

At first, Valentin was so defeated he could not even imagine a future for himself. His mentor, Magdalena Chadinoska Kuzmanoski, recalls that he could not tell her what he wanted to do because “nobody had asked him that before, so he didn’t know how to respond”.

Once he identified an interest in becoming a chef, Kuzmanoski arranged an internship for him at a burger restaurant, an experience that boosted Valentin’s confidence. “I see that I am good at whatever I try,” said the young man.

“From day one of training, they have praised me. They would even employ me as early as next week, but because I don't have documents, they cannot yet.”

That is now about to change. Once he has his ID card, Valentin plans to enroll in high school, become regularly employed at the burger restaurant, pursue culinary training, get a passport and travel outside the country for the first time in his life.

And he hopes many others will benefit from gaining a legal identity. “It's not only me out there," said Valentin. “There are many people in the country who do not have documents. I would like to send an appeal to everyone to resolve not only my case, but to also resolve the cases of everybody else in my situation.”

Now that his legal marathon is over, Valentin is eager to start building the life he always dreamed of and to feel like he belongs. “It will feel like home when I have a house, health insurance, a job; when I have a good life like other citizens who have rights.”