For Pakistani quake children, classes under canvas offer room with a view

For Pakistani quake children, classes under canvas offer room with a view

ABBOTTABAD, Pakistan, Feb. 20 (UNHCR) - It is an opportunity that has emerged from the rubble of a catastrophe. Fourteen-year-old Nazbergam and her sister Sabermina, 15, have been living in the Banda Sahib Khan relief camp in Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) since October's earthquake destroyed their home and those of much of their village. But amid the hardship is a reason to be grateful. For the first time in their lives, the teenaged girls are going to school.

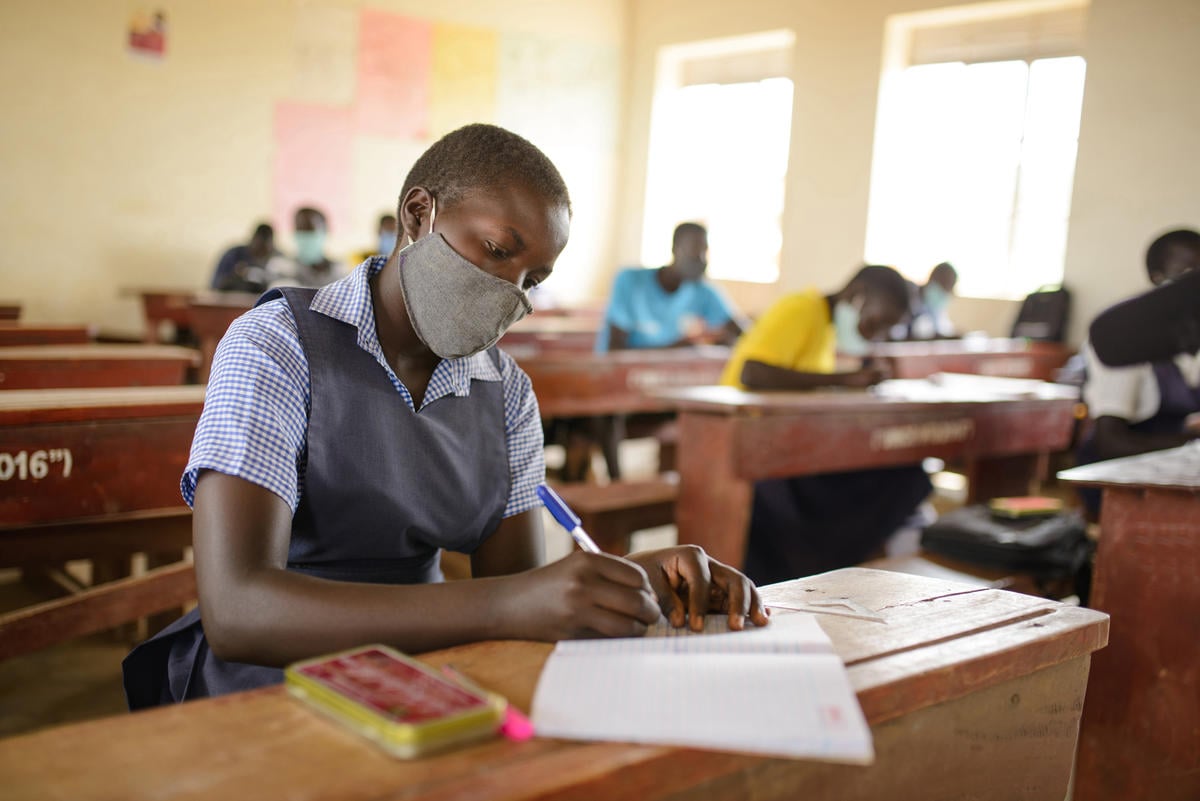

Across the quake-affected region, UNHCR partner agencies, such as UNICEF and Save the Children, have established improvised schools in relief camps providing young children, and some not so young, with access to education during the winter months. The facilities are basic, often no more than a note pad and a spot on a groundsheet, but the classrooms are full and the students boisterous.

Saima has been teaching at the Banda Sahib Khan school since it was established. She continues to receive her government salary, though her classroom in the town of Balakot, near the quake's epicentre, remains a pile of debris. Most of her new pupils are under 10, but several of the girls are as old as 17. For nearly everyone this is their first experience of a classroom.

"The older girls are very interested and eager," says Saima. "Their maturity means they learn more quickly than the younger children. But girls such as Nazbergam and Sabermina often feel a bit shy in the classroom."

Teachers, too, can find the demands of the camp schools challenging.

"Many children are coping with the loss of their homes and often the death of loved ones," says Saima.

Addressing the educational needs of such a diverse group while remaining sensitive to often fragile emotions can require a reinterpretation of traditional teaching methods.

School was never an option for most of these girls. Like Nazbergam and Sabermina, they were expected to help their mothers with domestic chores. Where village schools did exist, enrolment was often just for boys.

In the Meira relief camp, the largest in NWFP, teachers estimate that up to three-quarters of their female students had never previously attended school. As the agency responsible for camp management as part of the United Nations joint relief effort, UNHCR has been working with local authorities and partner agencies to ensure that facilities in the camps meet international standards.

Leila Mukaram, a UNHCR field officer, visits Meira camp daily to monitor operations.

"We now have 2,700 children attending classes during morning and afternoon sessions," she says, "But there are still children who aren't enrolled. To reach them we need to raise awareness of the importance of education among their parents."

Working alongside pupils half their age, Nazbergam and Sabermina have discovered a world which was previously off limits. Allowed into the classroom, they are now reluctant to leave.

"When we return to our village, I hope we will have an opportunity to continue our schooling," says Sabermina as she and her sister return to the family tent in a camp which has provided more than shelter.

By Larissa Bruun in Abbottabad, Pakistan