Nansen Award: Mine clearers help Lebanese farmers rebuild their lives

Nansen Award: Mine clearers help Lebanese farmers rebuild their lives

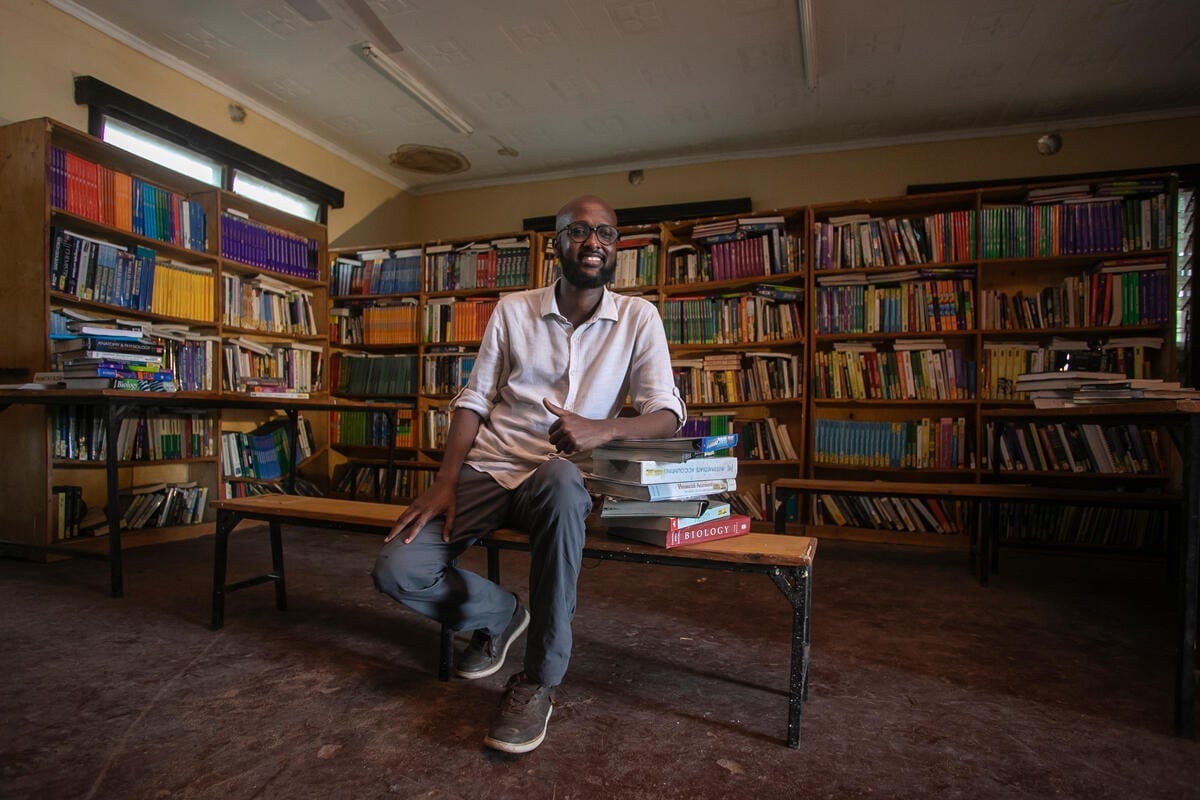

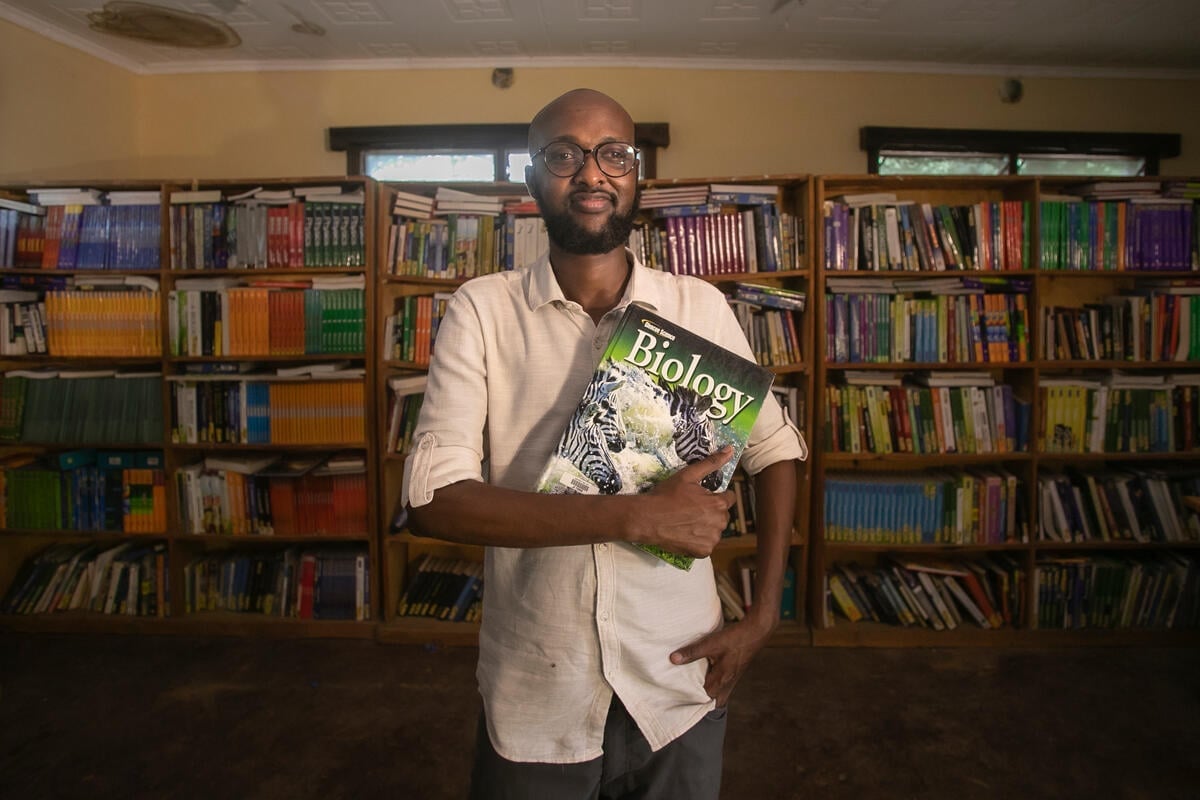

DEIR QANUON RAS AL EIN, Lebanon (UNHCR) - Fadlallah Soufan could not contain his joy when the civilian deminers arrived to clear the deadly clusterbomb harvest scattered over his land. It meant that he would no longer be in danger on his own property and could finally rebuild his life after the five-week war that devastated southern Lebanon in mid-2006.

"They removed around 1,000 bomblets. For more than two-and-a-half years, I have not been able to use my land or benefit from it," he said, referring to Lebanese and international staff from the UN Mine Action Coordination Centre-South Lebanon, winners of this year's prestigious Nansen Refugee Award.

Fadlallah grew bananas and vegetables on the 25,000 square metres of agricultural land that he rented in the village of Deir Qanoun Ras Al Ein. Harvests were good and he earned enough for a comfortable lifestyle for himself and his family, including three children.

That all changed in July 2006 when fighting erupted in the south between Israel and the Hezbollah movement. In the last days of war, large amounts of cluster bombs were dropped on the village - and his land.

This had a devastating effect on Fadlallah, whose main source of livelihood had all but gone up in smoke. "I was paying rent of 20 million Lebanese pounds (US$13,000) a year without any return," Fadlallah said of the months after the conflict ended.

"After the ceasefire, the situation was chaotic and crazy. We were finding clusterbombs every day, everywhere," said UNMACC-SL spokesperson Dalia Farran. "We realized the problem was huge. There were around 16 casualties on the first day alone."

Up to one million people fled their homes during the war. They may have expected some devastation, but were shocked to find the area littered with hundreds of thousands of deadly bomblets released from Israeli-fired clusterbombs.

"I have seen bombs before, but never as many as I saw on the day I returned after the ceasefire," Fadlallah said. "It was extraordinary. Bombs were planted in my land like seeds. It was a real tragedy."

Land for the southern Lebanese is an essential source of food and income, but it also has spiritual and emotional value. "The land is very precious to us, losing it feels like someone we love just died," Fadlallah explained. "When I saw my land full of bombs - on the ground, underneath it and even on trees - it broke my heart."

But as the soldiers moved out, UNMACC-SL teams moved in and started clearing the south of landmines, unexploded ordnance and the bomblets. Thousands of the clusterbomb submunitions were destroyed and cleared from roads, houses and fields in Deir Qanuon Ras Al Ein.

Some villagers, including Fadlallah, rashly tried to help. "I removed 700 small bombs with my own hands. I used to stack them in orange boxes. I had no choice but to go back to my land. Everyone was doing the same," he said.

He found out the hard way that the task should be left to UNMACC-SL when a friend was killed clearing his land. Even the experts face grave risks - bomblets have killed 14 mine clearers and injured more than twice that number since 2006.

Fadlallah now has his cleared lands back, but there is still a lot of work for UNMACC-SL to do before the south is completely safe once more. "They should ban cluster bombs. This is the only way for us to continue our life in safety," the farmer concluded.

By Laure Chedrawi in Deir Qanoun Ras Al Ein, Lebanon