Testing time for refugees with an eye on higher education

Testing time for refugees with an eye on higher education

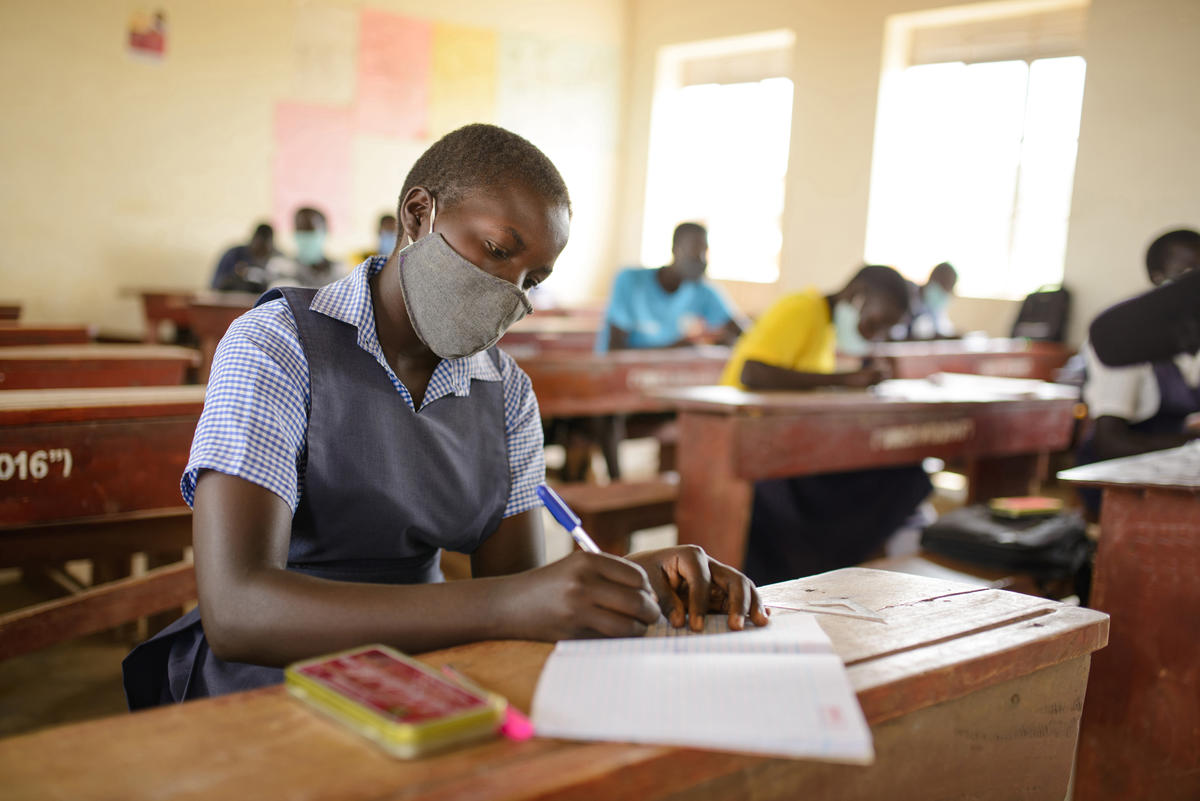

ABECHE, Chad, February 29 (UNHCR) - The 118 "mature students" from Sudan's troubled Darfur region are a study in concentration as they sit their finals at a secondary school in the eastern Chad town of Abéché.

Two Sudanese professors and several local teachers act as invigilators while the students, aged between 18 and 25, tackle tests that could book their passage out of an arid refugee camp and into a university in Africa or Europe.

As they rack their brains for the correct answers, these young people will probably be dreaming of becoming scientists, lawyers, physicians, agronomists and the like. With the help of UNHCR and its implementing partner, the Refugee Education Trust (RET), that goal is within reach.

A year ago, RET organized written tests in the 12 UNHCR-run camps housing some 240,000 Sudanese refugees in eastern Chad. The exams were aimed at identifying the brightest secondary school students, whose education in Darfur had been brutally interrupted by the civil war that erupted in 2003.

The top 118 were provided with books and encouraged to form study groups among themselves. The curriculum was supervised by the Khartoum-based International University of Africa, but with secondary school facilities in only three of the camps, the students would basically have to teach themselves.

"The exams are the same as those for regular Sudanese students who go to school every day," explains Muhammed Mabikir, one of the professors. "They cannot be granted exceptions. So if they get their diploma, it is really an enormous achievement."

The papers they sit are definitely aimed at separating the wheat from the chaff. "We carry this programme out in Senegal, Ethiopia, Somaliland and Chad. The average percentage of those who pass lies between 30 and 50," notes Mabikir, while adding that students can try again if they don't pass at the first attempt.

All students must take Arabic and Islamic education as well as either English or French. They can supplement these with a choice from mathematics, physics, biology, history, geography and environmental studies.

"English language and literature was the most difficult assignment," Nadwa, who lives in Gaga camp, says after the exams are over. "There is no one I can practise with at home," adds the 22-year-old.

Nadwa's family speak the language of the Massalit, a rural tribe of subsistence farmers living around El Geneina in West Darfur. She wants to study medicine at an African university and says, "As a woman I'm lucky, my relatives are very supportive. They want to have a doctor in the family."

Abdallah Yassir Mahamat, who wants to become an environmentalist, says he and fellow scholars in Treguine refugee camp found a few people to help them with their course work, "but for most of the time we had to find our own way."

The 24-year-old wants to specialize on water resources at an African university and use his degree and expertise to help rebuild Darfur, "If we have peace by then." He notes that one of the core reasons behind the conflict in Darfur "is because there is not enough water or wood available. People in the villages need to be more aware when making use of these scarce resources."

Now the students, including 23 Chadians from local villages, must wait for three months to hear how they fared; the results will determine the rest of their lives. UNHCR, which plans to boost secondary school facilities in the east Chad camps this year, will be rooting for all of them as their example will be an inspiration for tens of thousands of younger pupils.

That's a sentiment echoed by Mabikir. "The exchange with these Sudanese refugee students was very inspiring," he concludes, while packing away test papers. "They really made a big effort to get here and I hope they will all pass and get their diploma. Now they are refugees but one day they certainly can make a difference in society."

By Annette Rehrl in Abéché, Chad