Picture This

Picture This

Every so often you meet one person who makes you think, "I want to tell everyone about you." For me, that someone is Israa, a 13-year-old Syrian refugee living in Jordan's Za'atari camp. Even in exile, her spirit is unbreakable. "I might be in a camp now, but I won't be here forever," she tells me. "I will one day leave and realize my dreams."

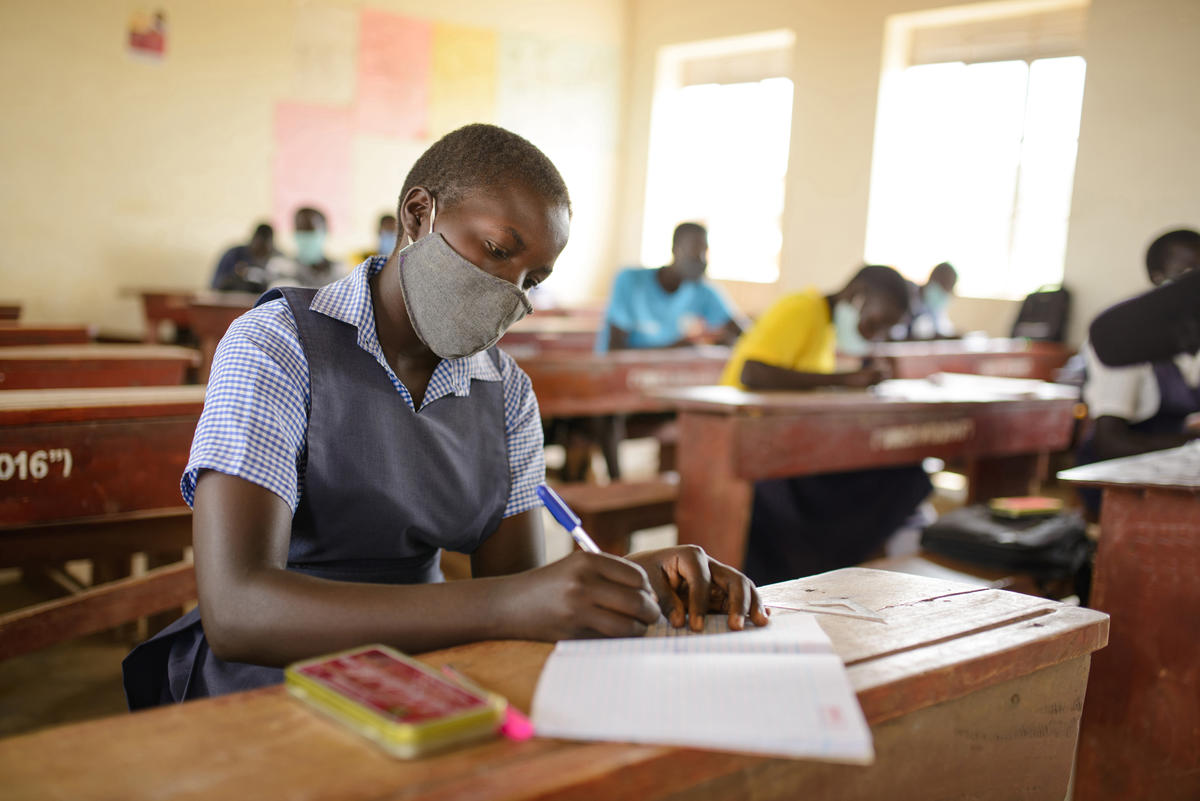

I meet Israa in a photography workshop run by UNHCR in the camp. The two-week course teaches Syrian refugee children basic photography skills and equips them with a camera, which they use to document their daily lives in the camp. Each student has a personal notebook in which they paste all the pictures they have taken once they are printed.

Israa sits at the front of her class. Wide-eyed and fidgety, she just can't sit still. I watch as she whizzes from one end of the classroom to the other, cracking jokes and being somewhat of a busybody. Within just a few minutes, she has managed to get into a confrontation with one of the teaching assistants. "This is a girl who knows what she wants," I think to myself.

Israa is loud and very proud. But she isn't rude. In fact, she is charming and hilarious. During class, the teaching assistant playfully teases her, but later says she is one of the most intelligent and thoughtful girls he has ever met.

The workshop isn't Israa's first encounter with photography. "My parents had a camera in Syria, but we left it behind when we ran out of our house," Israa tells me. I ask why they had to leave their house in Daraa so suddenly. "Do you know what it means when bombs start raining on you?" she replies. "You have no time to think of anything. Just run."

Like all Syrian refugees I meet, Israa's story is a sad one, one of loss and suffering. But this 13-year-old sees silver linings where most people would simply see black clouds. "These classes have taught me so much. Not just how to take pictures. The course gives you the curiosity to go out, seek and explore. It makes you think creatively and look beyond the obvious."

"My parents had a camera in Syria, but we left it behind when we ran out of our house."

During class, Israa flips through her notebook and shows me a photograph of a smiling child. She has called it "Happy children". The caption underneath reads: "Happiness, fun, childhood, hope and spontaneity. How I wish we had stayed children." Reading it breaks my heart. Israa is a child, but she feels as though she is not. When I ask her why she wrote that, she says: "You know, now we somehow feel older, we have to think and worry about things we wouldn't have had to before. In Syria, we just played and went to school. Now, you somehow feel you have to be responsible. I am not sure for what, but I just feel I am not a child anymore."

The Syria crisis has caused death, destruction and displacement on a horrific scale. Many of the children I have met speak of family members who were killed in the war. Often, they are traumatized. Thousands are out of school. The thing which breaks my heart the most is seeing children who feel they have nothing to live for. Children as young as five walk the streets selling tissue boxes or flowers or simply beg. Can you imagine your child doing this? Israa is one of the few who has found the strength to carry on and hold on to her dream.

"I want to be a doctor, a good doctor," she tells me. "I want to treat people with dignity and help those who cannot afford to pay for medical treatment."

Israa was lucky enough to leave Syria with her family. However, their journey was perilous. "When we left our house, we could hear bombs going off," she recalls as we sit together in class. "It was dark and we couldn't see anything. We got into a taxi and just hoped for the best."

As she speaks I try to picture what it must have been like. I'm hearing her but I can't believe that the nightmare she is describing was, in fact, reality.

"The taxi we were in wouldn't bring us all the way to Jordan. We walked through the desert for a whole day. I remember we walked from 3 a.m. until Athan el Esha [evening prayer]. We didn't eat or drink the whole journey. I remember we were so thirsty, it was unbearable. Our mouths were dry and our skin was burning. But we had to keep going. My brother's wife was pregnant. She lost her baby along the way. She was bleeding the whole way. We thought she was going to die. As soon as we arrived at the reception centre in Jordan she was transferred to the hospital."

"We didn't eat or drink the whole journey. I remember we were so thirsty, it was unbearable. Our mouths were dry and our skin was burning. But we had to keep going."

As she speaks, she looks away from me. Her tone is sombre. Then, she quickly changes the subject. "This is the first time I've owned a camera, you know. It's nice to have your own because then you are independent and no one can tell you to stop pressing things on it."

Do you remember your first camera? Was it a Polaroid or digital? Do you remember the first picture you took? How did it feel when you saw it?

I remember the first time I took my disposable camera to develop pictures I had taken on a geography school trip. I was ecstatic when I got handed over the envelope. I couldn't wait to open it and look through my pictures. My class and I had gone on a trip to Dorset, in southern England. Admittedly, my pictures were awful, but it didn't matter. I had captured some beautiful moments with my friends. Moments I can relive every time I look through them again.

Talking to Israa, I realize just how much we take for granted. Taking pictures is such a mundane thing to most people living in the digital age. But when you meet people like Israa you realize how much pictures can mean to people who have lost everything. Pictures capture moments we will never get back. If we are fortunate enough we will continue to create beautiful moments and take pictures. But when your life is ravaged by war and all your beautiful memories are burnt to ashes, creating new and beautiful memories is not that easy.

Many of the children in the workshop have taken photographs of their family members. Israa has taken a picture of her grandfather, and when I ask her why she says: "When we left our home we left all our pictures. Now we can take new pictures and keep them with us."

Listening to Israa was such a pleasure. She was wise beyond her years. I had only known her a few minutes but I was so proud of her. I really wanted her to realize her dreams. Every part of me was egging her on.

"You know, Bathoul, people expect girls to be shy and sit quietly. It's what they call being ladylike, isn't it? But I don't agree. I believe that women can speak up, say what they think, ask questions and still be feminine. Even if we say the wrong things, that's okay. This is how you learn. I do not think we should be ignorant and submissive just to appear feminine," she declared.

I couldn't agree more. If Israa were in my class, I'd vote for her to be head girl. I want her to speak on my behalf. I want people to listen to her. As she spoke, I thought, "I am going to write down every word she is saying and share this with people." Girls like Israa might be refugees by definition, but she is so much more. She is dynamite. War, displacement and loss have not broken her.

In fact, Israa has found something positive about her life in a refugee camp.

"When we were in Syria, we only knew our own areas, our village; we didn't know Syria. I only had friends from my village. In Za'atari, it's true that we are in a camp and we are all Syrians, but we have met people from all over Syria. We have made friends with people we probably would have never met or known of, we are mixing with people from all over Syria. You know, I feel I know Syria so much better than when I was living in it. Now when I go back, I want to travel across the country and see all these places inside my country which I might never have had the curiosity to go and see before I came to Za'atari."

As I say goodbye to Israa, I give her a tight hug. She has not left my thoughts since.

Israa is one of 3 million Syrian refugees under UNHCR's care. Whenever you read the statistics, I urge you to think about the person behind the number. Think about Israa. Each one of the 3 million is a living, beating heart. Each is a person with a story.