A mother’s struggle helps drive a national movement for legal identity in Nepal

A mother’s struggle helps drive a national movement for legal identity in Nepal

Deepti Gurung (left), founder of the Citizenship Affected People’s Network (CAPN), discusses a case with colleague Sangita Karki at her office in Kathmandu.

That Deepti regularly finds such joy in life belies her years-long struggle to win equal citizenship rights for women and legal identity for all in Nepal, a struggle that began at home with her daughters, Neha and Nikita, whose father abandoned the family when they were very young.

“I started this entire thing only with the qualification of being the mother of two daughters,” Deepti said on a recent humid monsoon morning in the office of her organization, the Citizenship Affected People’s NetworkLink is external (CAPN), in Kathmandu. The question that drove her was a personal one – “How can my country deny my children?” – but the answer would prove to be complicated.

Invisible people

Under Nepalese law, children could not inherit citizenship from their mothers, meaning Neha and Nikita had no legal identity, leaving them without a nationality. This cut off their access to basic rights and services, such as higher education or formal employment, a bank account, a passport or even a SIM card. “People without citizenship are invisible,” Deepti said. “Citizenship is the door to everything.”

Even if they live in their own country and have never been forced to flee their home or cross a border, those who lack legal identity fall within the remit of UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, which is mandated to prevent and respond to statelessness and advocate for stateless people worldwide. In recognition of her dogged pursuit of legal identity and gender equality in Nepal, Deepti has been named the 2024 regional winner for Asia of the UNHCR Nansen Refugee Award.

Deepti worked in the tourism industry in Nepal’s Pokhara Valley, a popular staging post for hiking in the Himalayas, and lived happily with her two young daughters in a close-knit all-female unit. By 2009, she had reconnected with and married an old childhood friend, Diwakar Chettri. He joined the family, the girls soon calling him ‘baba’ or father. “Life was beautiful,” recalled Deepti.

Deepti, her husband Diwakar Chettri (right), and her younger daughter Nikita (left) have a video call with her older daughter Neha, who is studying in the United States.

One day, Deepti’s daughter Neha, who is now 27, returned from school distraught: unable to provide her citizenship certificate, she was blocked from taking the secondary school entrance exam. Arguing her daughter’s case at the local government office, Deepti faced degrading interrogations by a series of male officials. They laughed at her, calling her a “virgin mother”, questioning her morality and her children’s legitimacy because of their biological father’s absence. “It was very painful. They were stripping me naked with their words,” Deepti said.

It was only then that she discovered her daughters’ citizenship – and so their futures – relied upon an undependable absentee father, a man who had walked out years earlier cutting off all ties, who had nothing to do with the family, and whose whereabouts were unknown.

The start of the struggle

This humiliating realization was the spark for Deepti’s activism. Feeling lost, isolated and alone, she started a Facebook group in 2012 called ‘Citizenship in the Name of Mother’. Momentum soon gathered and she was introduced to a lawyer called Meera Dhungana, of the Forum for Women, Law and DevelopmentLink is external (FWLD), an established and respected Nepalese non-governmental organization, who agreed to take the case of Deepti’s daughters to court. FWLD, a partner of UNHCR in Nepal, has long campaigned for gender equality, including a woman’s right to pass on citizenship to her children.

At the same time, Nepal was going through a constitutional review process and Deepti together with FWLD seized the opportunity: they would not just seek individual citizenship for Neha and Nikita, but a broader change in the law to allow women to pass on their nationality in the same way as men.

Deepti meets with lawyers Sushma Gautam (left) and Meera Dhungana (centre) from the Forum for Women, Law and Development (FWLD), which helped her secure citizenship for her daughters.

Five years of struggle followed, requiring determination, patience and stubbornness. There were hours and days spent waiting in a succession of government offices only to be told to return tomorrow, repeated visits to multiple officials, court hearings, petitions, meetings and protests. Deepti abandoned her job in tourism and focused all her efforts on the fight for citizenship.

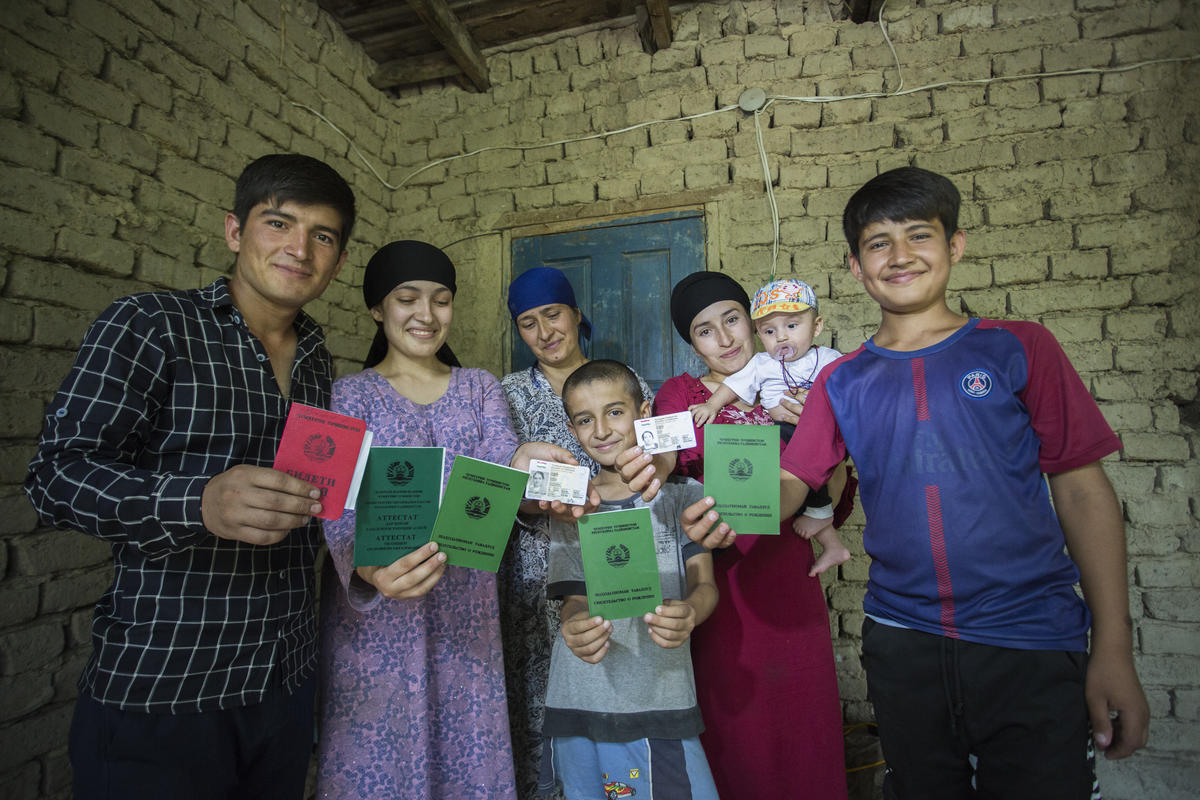

In 2017, her determination paid off when Neha and Nikita gained their citizenship through a court ruling. “When we finally got the verdict from the Supreme Court, I called [my daughters] up and we were in three different places jumping, screaming and all in tears,” Deepti said.

Fighting for others

Lack of citizenship is not uncommon in Nepal, either due to the gender discrimination that Deepti is fighting, or because many are unaware of their rights and have never applied for citizenship, or do not know how to.

Deepti’s husband, Diwakar, is a case in point. His father died when he was a child, and when his mother later sought citizenship for her children, their applications were denied. Deepti took up his case as well as those of his brother and nephew. At one point, she said, “I was fighting for five people in my family!” Diwakar finally won his citizenship five years ago, aged 45, and for weeks afterwards slept with his new identity papers tucked under his pillow.

Deepti has helped scores of undocumented people attain citizenship through her patient support navigating bureaucratic hurdles, most recently, her CAPN colleague Sangita Karki, 26. “I failed to win citizenship for nine years before I met Deepti,” said Sangita, who grew up in an orphanage and compared living without citizenship to suffering a disease without any treatment. Unlike others who had tried to help her over the years, “Deepti didn’t stop, it was every day, she refused to give up.”

Even as the individual victories rack up, the struggle for constitutional change continues. Nepal’s new constitution in 2015 allowed mothers to confer citizenship for the first time, but only in limited and specific cases, such as through naturalization if the father is foreign, or if the father is publicly declared “unknown”.

Together, Deepti, FWLD and a broad network of organizations in Nepal are advocating for a constitutional amendment that would ensure mothers can pass on citizenship on an equal basis with fathers. “There’s no option other than winning this fight for equality,” she said.

The promise of equality

Today, Deepti lives with Diwakar and Nikita, 24, in Godawari, a tranquil suburb on the southern outskirts of the capital, hard against the steep forested hills that surround the broad Kathmandu Valley. There is no clearer proof of the opportunities afforded by legal identity than in Deepti’s own family.

Deepti Gurung hugs colleagues at her office in Kathmandu after revealing that she has been named 2024 regional winner for Asia of the UNHCR Nansen Refugee Award.

Since winning their citizenship, Diwakar has enrolled in a Masters in English language teaching, Neha has won a Fulbright scholarship to study law in the US and Nikita is completing her undergraduate degree in business administration. In 2023, using their new passports, the whole family travelled abroad on holiday, visiting Thailand, where they saw the ocean for the first time. Looking out at the sea, Deepti thought to herself: “This is what freedom feels like.”

Deepti’s determination to pry open the locked door of citizenship means her family, and the others she has helped, can embrace a new world of opportunity and equality.

"There’s no option other than winning this fight for equality."