Lebanon puts in an extra shift to get Syrian refugees into school

Each weekday lunchtime, the walls of Bar Elias School in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley reverberate to the sound of more than 1,600 children noisily making their way to and from class. A fleet of school minibuses disgorges pupils ready to begin lessons for the day, before quickly filling up again with those heading home.

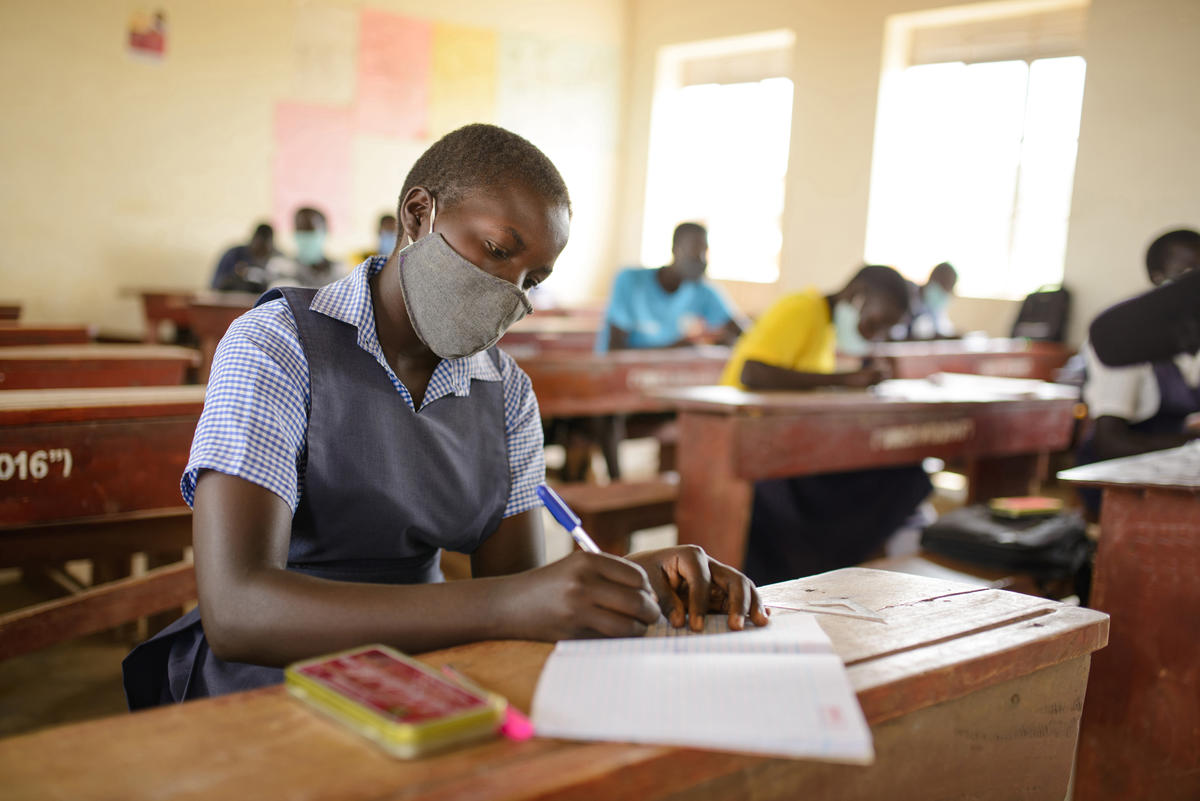

Surrounded by fertile fields bursting with vegetables and grain, the school is one of around 350 in Lebanon operating a “second shift”. The system essentially fits two school days into one, with afternoon shifts across the country providing an education for about 150,000 Syrian refugee children.

Lebanon hosts some 987,000 refugees from Syria’s seven-year conflict, 490,000 of whom are children of school age (from three to 18 years old). About 220,000 Syrian children attend lessons – as part of the second shift system or in morning classes alongside Lebanese pupils – but more than half are not in school.

At Bar Elias, 770 Syrian pupils attend the afternoon shift in classes of about 35. The curriculum, teaching materials and most of the teachers are the same as those for the Lebanese children who attend morning lessons.

"I was very happy to have this opportunity to attend school."

Moaed, 13, is one of the Syrian pupils in the afternoon shift. He fled Raqqa four years ago with his family to escape the extremists who controlled the city, and still struggles to put the memories behind him.

“I still remember how [they] beheaded people in my town,” he said. “I saw it with my own eyes. This is one thing I can’t forget, but I try to erase these memories.”

Shortly after arriving in Lebanon, Moaed and his family learned that Syrians could enrol in Lebanese public schools, and the certificates would be recognized in Syria. Having already fallen behind because of the conflict, he jumped at the chance to resume his studies.

“I was very happy to have this opportunity to attend school. I loved it from day one,” he said. “I missed two years of schooling because of the war. I should be in grade seven but I am now in the fifth grade.”

The school’s principal, Ehsan Araji, says Bar Elias is operating at full capacity to try to provide an education for as many Syrian refugees as possible, but even so they are sometimes forced to turn others away.

“Because the school is located where Syrian refugees are populated, we struggle sometimes,” he said. “We have waiting lists, and sometimes if we can’t accommodate more students, we send them to other nearby schools.”

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, provides material support to Bar Elias and other schools in Lebanon in the form of books, furniture and other supplies, as well as paying to rehabilitate and expand school buildings.

The agency also provides direct financial assistance to schools, and runs programmes to encourage Syrian children to enrol and remain in education, including homework clubs, parent engagement groups and education liaison volunteers who act as a link between schools, pupils and parents.

"With this education, they will build something for the future."

Moaed’s desire to become an engineer means he must do well in mathematics and his teacher, Mohammed Araji, said his ability and drive are typical of many of his Syrian students.

“There are very smart students here," he said. "They get good grades and are quick learners. Syrian students have big hopes. Some want to be engineers, others want to be doctors, despite their difficult situations. Sometimes the camp may be far from the school, but the student insists on coming to be able to get a certificate, and to improve themselves.”

Mohammed hopes the refugee children he teaches in the afternoon shift will one day put what they have learned to work when they are able to return home.

“With this education, they will build something for the future,” he said. “They will tell their children: ‘We were once Syrian refugee students away from home in Lebanon, and there was war, but we had ambitions and we were able to reach them’. This will encourage others to do the same.”