A learning curve for young Syrian refugees at model school in Lebanon

A learning curve for young Syrian refugees at model school in Lebanon

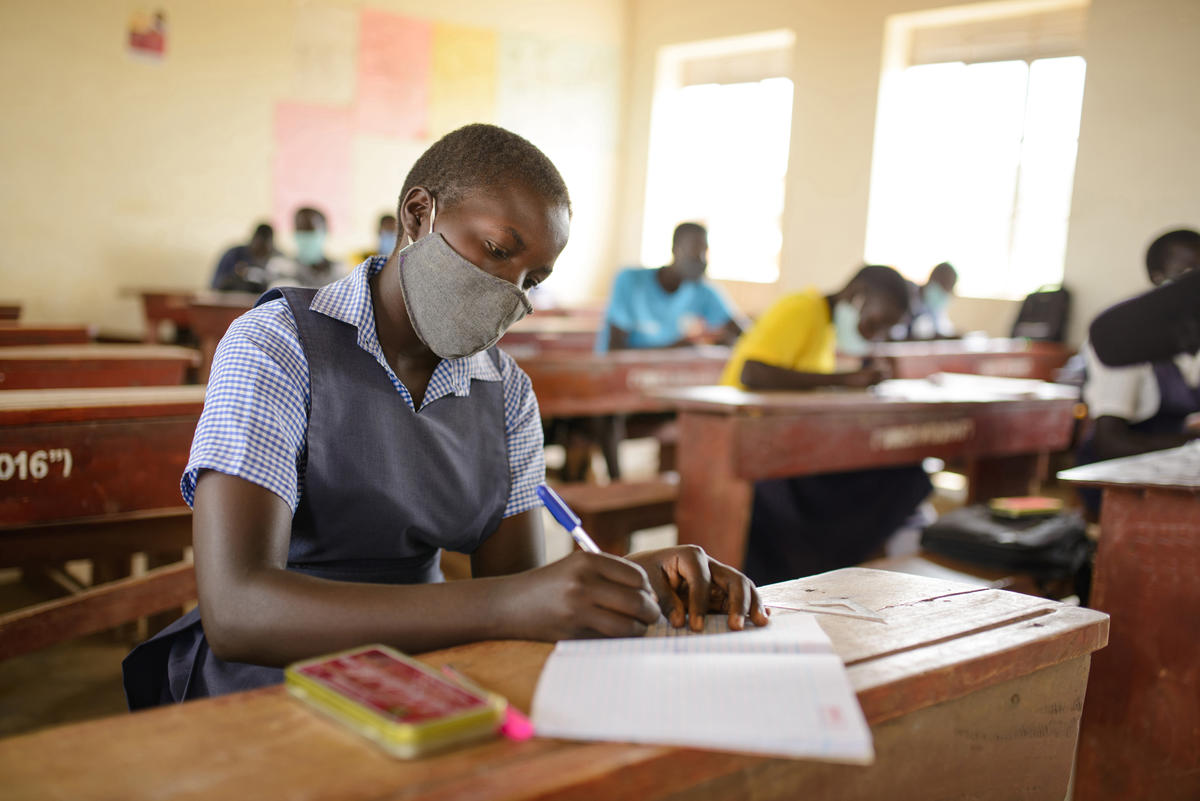

ARSAL, Lebanon, May 23 (UNHCR) - It's test day at the Arsal Public Second Shift Middle School and the students in the 8th Grade maths class are engrossed in their exam. They factor numbers, write a series of equations in the form of a single power - all in French, a language they have come to learn only since starting school here in north-east Lebanon two months ago.

"These children come to school with a deep desire for learning," says Ali Hujeiri, 55, the school principal. "They know what they've missed and now they appreciate the value of their education."

They have arrived from Syrian towns and cities such as Qusayr, Dara'a and Homs - places that are now battlegrounds. At least one of the boys in the class has seen his home blown to pieces. But somehow the silent walls of school that provide them a place for study also nurture a sense of hope beyond conflict. Here Billal, aged 11, can dream of becoming a teacher. Halid, also 11, aspires one day to be a doctor. Ten-year-old Selieman wants to be a hairdresser.

Arsal was once a sleepy town nestled in the hills a few kilometres from the Syrian border. When war broke out in Syria two years ago, the town bulged as civilians, most of them women and children, fled to Lebanon. Soon Arsal grew by 10,000 people - roughly half were children.

There wasn't enough room in the schools to handle all the newcomers, so the municipality was asked by the Lebanese Ministry of Education to create a second shift between one and six in the afternoon. Arsal Middle School gladly complied and 236 Syrian students were enrolled. "I look at these children and I say, 'What in this war is their fault?'" says Hujeiri. "They didn't do anything to deserve their fate. These children need to be educated."

Throughout Lebanon almost 40 per cent of the refugee population is of school age. But enrollment in the education system remains critically low. In the current academic year, only 30,000 of the estimated 120,000 school-age refugee children go to state schools.

It is estimated that another 10,000 receive some form of private education. This level of refugee participation in education is nowhere near the ambitious goal set by the Lebanese government to have 60 per cent of all refugee children in school.

While the Ministry of Education has promised that all refugee children are entitled to attend a state school, many schools are either overcrowded or lacking in basic resources such as books.

The Arsal approach of double shifts represents one solution. Tuition fees, which cost US$136 per term, are paid for by the UN refugee agency. Other UNHCR partners fund books, supplies and other educational needs. The Syrian students arriving in the village are unfamiliar with the Lebanese curriculum or the French language in which some courses are taught, but they have managed to excel in just a few months.

"We see the approach that Arsal has taken as a model for the rest of the country," says Linda Kjosaas, a UNHCR education expert in Lebanon. "With an increasing influx, the number of children in school-age at the end of 2013 will exceed the current number of children enrolled in state schools, and in some places even a second shift will not solve the space problem. The impact of the conflict is staggering, but despite what these children have had to endure in the past, they need to be given a real chance to further their education and not become a lost generation."

The refugee children of Arsal still face daunting problems. Many children cannot go to school because they are required to work by their parents. Others are traumatized by war as well as the transient nature of their lives. "It is the lack of stability that has affected them the most," says the school principal, Hujeiri. "They don't have food on their tables each day. They don't live in the same place every day."

To that extent, the educational environment at the school is more than just a learning tool. It is a way to create a shared space of safety. Children who are not in school are at much higher risk of ending up as child labour. Moreover, it would be more difficult for the government and humanitarian agencies to identify the health and other needs of the young not at school.

"For many villages, the school is the heart of the community, and to be able to bring children to the safety of a school and offer them needed services is very important. Quality education is the only way for these children to integrate well in their new reality and have a real chance for a future," notes Hujeiri.

Currently UNHCR, UNICEF and partners are planning for next year's Back to School programme. With a forecast number of 300,000 registered refugees in school-age in Lebanon, the costs of failure for these students is simply too high and so a strong spirit of cooperation has flourished between school officials, local government, UNHCR and other key partners. "We are all team players here," says Terra Mackinnon, UNHCR associate field officer. "Gold stars for collaboration for everyone!"