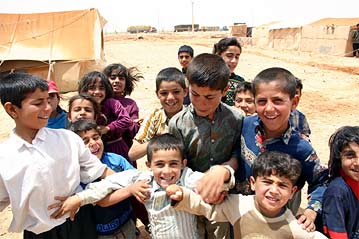

Feature: It's no boy's life in no man's land

Feature: It's no boy's life in no man's land

RUWEISHED, Jordan (UNHCR) - Twelve-year-old Massoud woke up one morning in a refugee camp in the no man's land between Iraq and Jordan and told his mother he wanted a Coca-Cola. "We have no money, my son," she told him. "We can hardly survive, there is no money for any extras."

An Iranian Kurd, Massoud had been living since the summer of 2003 in what was supposed to be a temporary camp in the desert along the main highway leading from Jordan into Iraq. His family had left Iraq after the bombings in March/April 2003 in an attempt to find a place where they could live in peace and freedom.

Prior to no man's land, they had lived for more than 20 years in Al-Tash refugee camp, west of Baghdad, where they had sought refuge in the aftermath of the Islamic revolution in 1979. Other Iranian families of Kurdish origin joined them at the beginning of the Iran-Iraq War in 1980. At the beginning of 2003, over 12,000 Iranians of Kurdish origin were living in the camp.

Amid the bombings that followed, about 1,200 refugees left Al-Tash camp in search of another home outside Iraq, while some 1,600 made their own way to the northern governorates, primarily to Sulaymaniyah. Others repatriated spontaneously to Iran.

Massoud's family chose a new life - away from Iran, Iraq and out of the camp. They departed for Jordan, hoping to be allowed entry into the country or any other country in or outside the region. Little did they know that they would end up again in a camp, this time in the middle of nowhere, in no man's land.

The UN refugee agency, CARE, the Hashemite Jordanian Charity organisation and other agencies have been working to support and assist the more than 1,500 Iranians, Iranian Kurds, Palestinians, Sudanese and Somalis stranded in no man's land and Ruweished camp just inside Jordan.

Over the past year, UNHCR has worked closely with the Jordanian government to try to find solutions for the Iranian Kurd and Palestinian refugees. Last year, Jordan accepted 386 Palestinians with Jordanian spouses who had fled Iraq for the border camps. The remaining Palestinians said they wanted to go to their homes in the West Bank and Gaza, and even to Israel. This has not been possible so far, and this year one group decided that the best way out would be to go back to Baghdad.

As far as the Iranian Kurds are concerned, repatriation or relocation to northern Iraq could be an option for some. Ultimately, though, resettlement is likely to be the only solution.

In the meantime, life is hard for those who remain in no man's land. Living on top of each other, worried about the basic standard of life, exposed to cold winds, scorching heat and wild animals, they are high on stress and low on tolerance.

"Today I will make sure I earn some money, so I can buy a Coke for myself and something for my family," Massoud - tired of living in poverty, in a tent, in the desert, amid sandstorms and haunted by snakes and scorpions - told his mother.

So off he went, out of the camp gate where his camp mates gathered daily to charge their mobile phones and watch the "real" life outside go by. He went onto the main highway, where hundreds of massive trucks and cars pass every day between Iraq and Jordan, carrying businessmen, transporters, journalists and the military. He was going to sell some of the goods that were handed out for free by the aid agencies.

"We were not around when he went out," his mother and aunt said later. "He would never ever go out of the gate, but that day he did. They told us he was playing with other kids and every time a car passed by, he would show them his goods."

A huge truck hit Massoud on the main highway. He was killed on the spot.

Bone-chilling wails filled the cemetery of Ruweished town. Massoud's father crying for the son he could not bring back. His mother, stunned, silent with grief. The burial of a 12-year-old boy who never chose Ruweished to be his final home. Who just wanted a soft drink in the harsh desert.