Separated by the Sea

Separated by the Sea

Over 30,000 refugees and migrants travelled through South-East Asia in 2015, including about 1,000 who made perilous journeys across the Malacca Straight from Indonesia to Malaysia or who attempted to reach Australia from Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Vietnam.

According to a new UNHCR report, hundreds perished, mostly from starvation, dehydration, disease and abuse by people smugglers. Sea crossings originating from the Bay of Bengal continued to be particularly treacherous, with a fatality rate three times higher than in the Mediterranean Sea. Twelve of every 1,000 people who embark from there do not survive the boat journey, meaning that as many as 2,000 Bangladeshis and Rohingya may have died in the past four years.

Meet four of the hundreds, if not thousands, of families in South-East Asia who were separated by the sea in 2015.

Kasim

In some ways, Kasim is a typical 17-year-old. His favourite article of clothing is his FC Barcelona jersey. He wants to be a doctor. He does not listen to his parents, and even ran away from home. But the jersey is a donation. As a Rohingya, Kasim was not allowed to attend high school and the home he ran away from was a refugee camp in Bangladesh, 1,900 kilometres away. It was his birthplace – Kasim has been a refugee his entire life.

Primary education was available in the camp, but the schools there have only recently been permitted to extend their curriculum up to year eight. When Kasim finished primary school a few years ago, no classes beyond year five were available to refugees. So he thought of other ways to get an education.

First, he pretended to be Bangladeshi, enrolling in a local high school for three years with some other refugee children. He was preparing to enter year nine when administrators at the school discovered that Kasim was a refugee. He was expelled.

Kasim’s mother told him to put aside his dream of being a doctor. “We can’t accomplish that,” Kasim remembers her saying. “I’m so sorry.”

But Kasim was undeterred. “I decided myself that I’ll go to another country,” he recalls. “Maybe someone or some government will allow me to study.”

Kasim knew many other Rohingya who had paid smugglers to take them to Malaysia by boat, but his parents would not allow their only son to go. Desperate to learn, Kasim defied them, leaving the camp one night in March 2015 without their knowledge. A smuggler offered to take him to Malaysia without any up-front payment, and Kasim embarked on a small vessel from Teknaf, before eventually boarding a larger boat that took him into Thai waters.

“I decided that I’ll go to another country. Maybe someone will allow me to study.”

For nearly two months, he crouched shoulder to shoulder alongside hundreds of other passengers, with no toilet except for a couple of wooden planks held aloft over the sea by iron rods welded to the outside of the hull.

When smugglers abandoned their human cargo en masse in early May 2015, Kasim was transferred to a boat that was prevented from landing by authorities before a deadly fight for drinking water erupted, killing at least 13 people. Another passenger was already dead after the ship’s captain shot him in the head for unknown reasons. The man was wrapped in a longyi, given funeral rites and thrown overboard.

After the fight, Kasim was rescued by Indonesian fishermen and brought to a temporary shelter. He had given up everything – his home, his family and very nearly his life – for the chance of an education, but little had changed. He was still in a camp. He still had no school to go to. And he still wanted to be a doctor.

Hassan and Fatima

In his hometown of Buthidaung, Myanmar, Hassan was a driver for a local Rohingya leader. But when intercommunal violence engulfed the area in 2012, extremists began to target him. He fled by boat to Malaysia, forced to leave his wife, Fatima, and their two young children behind.

“Don’t cry,” he told his son, after finally finding the means and a smuggler to bring them over two years later. “We’ll be seeing each other very soon.”

Hassan agreed to pay a total of 11,000 ringgit (US$2,670), with half to be delivered by Fatima before she embarked and the rest settled upon the family’s arrival. They expected to reach Malaysia within three weeks. That was in March 2015.

Forty-seven days after their departure, Hassan received a call saying his family was near Thailand and that full payment was due immediately. “I told them I didn’t believe them,” he says. “Unless I had my family in my hands.”

But his sons were just five and two years old. The longer his family lingered, the more likely they would be arrested, fall ill or die. He had no choice. Hassan paid.

“Don’t cry. We’ll be seeing each other very soon.”

He did not hear from anyone for 11 days, until he received two missed calls from an Indonesian number while he was at work. He called back, but the number was no longer in service. Later that day, his phone rang again.

“Assalamualaikum,” said a familiar voice.

“Allah saved you,” Hassan said to Fatima, through tears.

“I had new life,” Fatima remembered. “We were dead in the sea.”

She told Hassan that her boat had been towed towards Malaysia by the Indonesian navy, and then towards Indonesia by the Malaysian navy, before a deadly fight broke out between Bangladeshis and Rohingya onboard. The boat was sabotaged and, as it sank, Fatima and the children were rescued by fishermen.

“I am happy they are alive, in a safe place,” Hassan told UNHCR back in June 2015. “But I want to see my children. That’s all I want to do.”

Abdul Rashid and Senowara

“I have no space to live,” Abdul Rashid told his wife, Senowara. It was one of the last times he saw her and their newborn child, over a year ago, when Abdul Rashid was preparing to leave their home in Maungdaw, Myanmar. As a mullah, a religious leader, he felt targeted, and was desperate for a way out. “If you can’t find me,” Abdul Rashid told Senowara, “Please understand I’ve left already.”

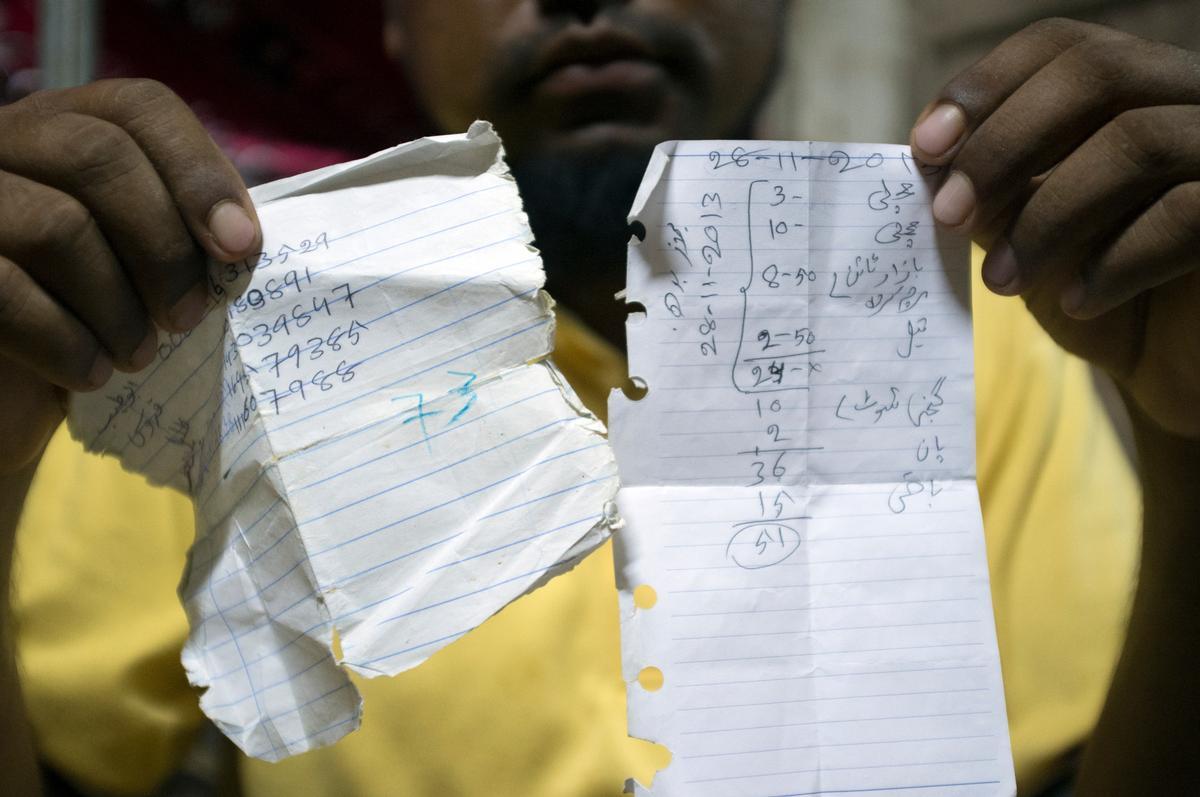

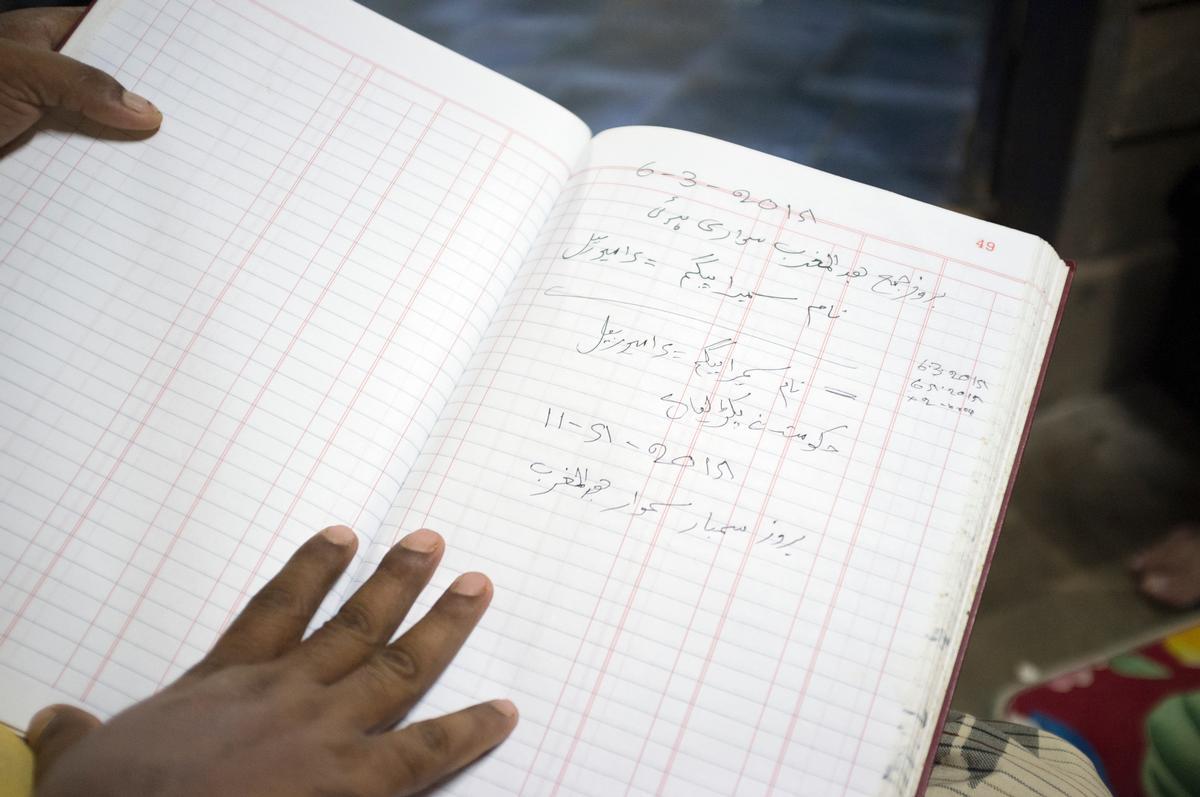

In January 2015, a smuggler offered to take Abdul Rashid to Malaysia by boat for just 50,000 kyat (US$40) up front, with the understanding that Abdul Rashid would work in Malaysia for months, if not years, to pay off the full cost of the journey, which can be as much as US$2,000. Abdul Rashid remembers the smugglers counting out over 1,000 passengers on his boat, dozens of whom died along the way from deprivation and beatings by the crew. He crouched next to another Rohingya man from Maungdaw who starved quietly until, one night, he could no longer be woken.

After being held on land for weeks, near the spot where authorities later found the remains of over 200 Rohingya and Bangladeshis, Abdul Rashid made it to Malaysia in March 2015. He began working in construction and carpentry, sending whatever he earned back to Senowara, so that she and their baby could join him.

By May 2015, Abdul Rashid knew his wife and son were at sea, but he had no idea where. A few days later, she called, saying the entire crew had abandoned ship in a speedboat and directed the passengers towards Malaysia. They and over 5,000 others had been cast adrift in the Andaman Sea when smugglers found they could no longer disembark their human cargo undetected.

“If you can’t find me, please understand I’ve left already.”

Their baby was sick, Senowara told Abdul Rashid over the phone. He became desperate to get them off the boat and so, despite warnings not to, called one of the smugglers, unsolicited. He has a recording of the call, which begins with Abdul Rashid introducing himself as a mullah.

“My wife is with our baby, and the baby is sick,” Abdul Rashid tells the smuggler. “I would like to request you to kindly bring them to shore.”

“Mothers with small children,” says the smuggler. “There are 22 mothers and 22 small children.” He explains that the women and children have been particularly difficult to disembark, because they are less able to walk through the night undetected. “Can we stop the children from talking?” the smuggler asks, rhetorically.

“Brother,” says Abdul Rashid. “My child isn’t big enough to talk. He isn’t even one.”

The boat carrying Abdul Rashid’s wife and child was one of two that arrived in Langkawi on 11 May 2015, with a total 1,110 passengers, including 375 Rohingya. All were transferred to the Belantik Immigration Detention Centre in Kedah, where the Rohingya remain detained nine months later. Almost all the Bangladeshis have been repatriated.

Working without legal status in a foreign country, as his wife and child languish behind bars, Abdul Rashid now wrestles with his decision to leave Myanmar. “I wouldn’t tell anyone to take this journey,” he says, his voice full of anguish. He remembers the unbearable suffering his family endured back home, but also cannot help yearning, he says, “to stay in a country that you can say belongs to you.”

Rohima, Ali and Shahida

“We lost everything,” says Rohima, as she recalls the intercommunal violence that wracked Sittwe, Myanmar, in 2012. As her village burned, Rohima sought safety wherever she could find it, and joined other Rohingya boarding fishing boats bound for Malaysia. But she could only afford to take one of her three children with her. Faced with an impossible choice, Rohima took her youngest son, who was eight at the time. She left her older son Ali, then 15, and daughter Shahida, 11, with their aunt.

After reaching Malaysia, Rohima was detained for four months. UNHCR helped secure her release and she began working as a street cleaner, hoping to save enough money to eventually bring Ali and Shahida over. “I am making money, I am working,” she would tell them over the phone. “I will bring you here.”

By early 2015, Rohima still did not have enough money for the journey, but Ali and Shahida insisted on joining their mother and younger brother. “They miss you so much,” their aunt told Rohima over the phone. “They are crying for you.”

In April 2015, when smugglers in Sittwe offered passage to Malaysia without any up-front payment, the family decided to risk the journey even without the means to pay. On the way, Ali and Shahida were moved from boat to boat, as smugglers jockeyed to unload passengers whose relatives could not afford payment. One boat they were transferred to was rumoured to be a kind of floating market of bad debt, where new smugglers could assume the passengers’ payment obligations at a lower price, confident they would eventually be able to extract the funds.

“They miss you so much. They are crying for you.”

In between these transfers, Rohima received a call from a smuggler who claimed that Ali and Shahida were in Thailand, and it would cost 6,000 ringgit (US$1,440) to deliver them to Malaysia. They put Ali on the line.

“While he was talking to me, he was saying he was being beaten,” said Rohima. “His voice was so faint, so small.”

Rohima later learned that Ali and Shahida were actually still at sea. But it made no difference – she had no way to pay.

Three days later, Rohima’s phone rang again. It was Ali. He and Shahida were in Indonesia. The last boat they had been transferred to was the first that disembarked there in May.

In June 2015, UNHCR arranged a Skype video call between Rohima and her younger son in Malaysia, and Ali and Shahida in Indonesia. It was the first time they had seen each other in three years.

“You look healthy,” Rohima told Ali. “Take care of your sister.” She told Shahida not to cry.

Their little brother bounced around, trying to squeeze himself into the view of the phone camera. “You look handsome now!” he told Ali.

At the time of writing, Ali and Shahida were believed to have spontaneously departed from their temporary shelter in Indonesia. Their whereabouts are unknown, and Rohima’s phone number is no longer in service.

This article was produced by UNHCR’s Regional Maritime Movements Monitoring Unit in Bangkok, Thailand. In 2015, the unit interviewed over 1,000 refugees and migrants who travelled by sea in South-East Asia. This account is based on interviews with survivors and their relatives, as well as media reports. The primary contributors were Keane Shum, Sarah Jabin, Fahmina Karim and Saw Myint.