Latin American nations urged to accede to statelessness conventions

Latin American nations urged to accede to statelessness conventions

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina, November 11 (UNHCR) - At the end of last year only 118 people were registered as stateless throughout Latin America, out of more than 6 million worldwide. But just as the world estimate of all stateless people is 12 million, the number of people in the region without citizenship is also probably much higher, with most of them coming from other continents.

And on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the UN Convention on Reduction of Statelessness, the UN refugee agency is keen to help these stateless people by getting more Latin American countries to accede to the 1961 convention and the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons.

The problem of statelessness and accession to the two conventions will be discussed during an important meeting today in Brazil on refugee protection, statelessness and mixed migratory movements in the Americas. Senior UNHCR officials and representatives from 20 countries are attending the gathering, hosted by Brazil's Justice Ministry.

Most of the stateless people in Latin America have come from other continents and many are caught in mixed migration flows, but there are also people within the region who have no nationality for one reason or another.

And lack of nationality can have a devastating effect on a person's daily life; it can affect access to health care, education, property rights and the ability to move freely. They are also vulnerable to arbitrary treatment and crimes like trafficking. Citizenship is vital for a person's welfare and participation in society.

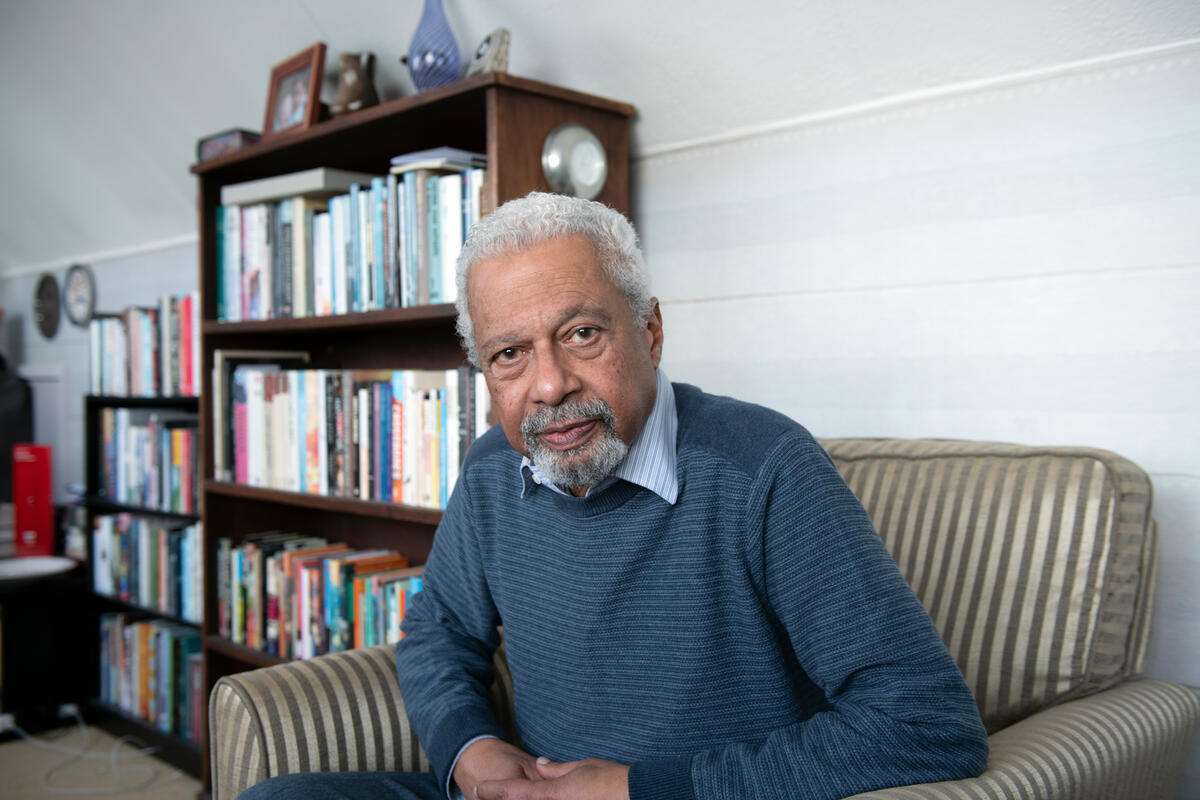

Miguel Kreiter, a registered stateless refugee in Argentina, was born in Austria in 1945 shortly after his family fled from the Soviet Union at the end of World War Two. He obtained legal residency and possessed an identity card for foreigners.

He did not realize that he had a problem until he applied for a passport so that he could visit close relatives living in Canada. Kreiter was told that he was not recognized as a citizen by the Russian Federation, Austria or Argentina - he was stateless and ineligible for travel documents. "I didn´t know what it meant to be stateless . . . I did not know about my rights or whom to ask for assistance," he told UNHCR. "I was nobody and I felt I could not do anything."

The 65-year-old carpenter said that his sister would face the same problem when she tried to travel.

But at least Kreiter's problem is out in the open and he can do something about it. Moreover, Argentina is among the Latin American countries that are parties to the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, but it has not yet acceded to the 1961 convention and has yet to set up formal procedures to determine statelessness.

Many other countries in the region have not even acceded to the 1954 convention and have no mechanism for recognizing the stateless and assisting them. Moreover, nationality laws in some Latin American countries contain gaps that could generate new situations of statelessness.

At the meeting in Brasilia, UNHCR will be urging participating states to redouble their efforts to prevent and respond to statelessness. Accession to the two conventions would be a major step forward.

Meanwhile, Kreiter has been recognized as a stateless refugee by Argentina and will be given a travel document. He is applying for citizenship. Millions of others around the world are not so lucky.

By Juan Ignacio Mondelli in Buenos Aires, Argentina

Francesca Fontanini in Bogota, Colombia, contributed to this article.