Child sexual violence survivor faces bleak future in Niger

Child sexual violence survivor faces bleak future in Niger

Kidnapped and held captive by Boko Haram militants at just 13 years of age, Adia* faced a bleak choice: marry one of the fighters, or face public execution.

“They would bury people alive, leaving just their head above the ground until they were dead,” she explains. “If you speak, if you beg for pity or mercy for the person, then they execute you too,” she adds.

Snatched by the group near Nigeria’s border with Niger, Adia had been held captive for five months. Separated from the boys, they were held inside the compound surrounded by a high spiked fence, their every need at the whim of their captors.

“We ate and drank when they felt like it. We often went days without food,” she says.

The boys were there to train to fight. The girls were there to become their wives or otherwise to become human bombs – being forced to enter villages and markets with explosives strapped to their bodies, which are detonated remotely by Boko Haram.

“They would bury people alive."

While they awaited their fate they were forced to work like slaves, and when they were not working, they were subjected to ‘religious teachings.’ If they did not follow orders, they were beaten.

The militants would come to take the girls one by one, to marry one of the fighters. When they came for Adia, she refused. Others who had refused were publicly executed in front of the children.

Fortunately for her, the leader of the Boko Haram group decided to grant her some more time to change her mind. In the meantime, a battle broke out nearby, and most of the fighters left to fight. A group of young girls and boys seized the opportunity to escape, knowing that if they were caught, they would face the public executions they had witnessed.

The group walked together at night for a week before they reached Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State in northeastern Nigeria. There, Adia took a vehicle going to neighbouring Niger, where she was told that she would be safe. Sadly, her ordeal only deepened.

Adia reached Kindjandi, in Diffa region in southeast Niger, which hosts approximately 25,000 people uprooted by violence, including refugees and internally displaced children, women and men. She had nothing but the clothes she was wearing, and no knowledge of where her family were. Forcibly married at 13 to a man 20 years her senior, her husband had disappeared.

A group of young girls of a similar age took pity on her and allowed her to share their shelter. But with no means of earning an income, and no humanitarian aid, the youngsters had little option but to resort to prostitution, or more accurately “survival sex.”

“I fell pregnant very quickly, after just a month or two... I have no idea who is the father of my baby” she says, as she rocks her baby on her knee. He is a year and a half old.

“I don’t like to do what I do... but if I don’t, he will go hungry. Often they don’t pay me, they just give me some food that I share with my baby. If I can’t find a man in the day, then we go hungry that night,” she adds.

The 15-year-old’s story is unfortunately all too common. Adia is one of more than 118,000 Nigerian refugees in Diffa who have fled Boko Haram, as well as more than 25,000 Nigerien nationals who were forced to return from living in Nigeria due to the conflict.

Almost 105,000 persons have also been internally displaced in the Diffa region itself, since the violence spread across the border from Nigeria in 2015.

More than half of those force to flee are female, while 55 per cent of them are under 18 years of age. At least 3,500 of these people are survivors of sexual or gender-based violence, known as SGBV.

“SGBV can take many forms. Violence and abuse affect not only women and girls who have fled Boko Haram, but the entire family, the community as a whole, destabilizing, humiliating, marginalizing and stigmatizing,” says Alessandra Morelli, the representative for UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, in Niger.

"We need to recognize SGBV as a crime."

The plight of young girls being kidnapped and forcibly married or used as human bombs by Boko Haram came under the spotlight in 2014, when almost 300 girls were kidnapped from a school in Chibok, in Borno. However, this was not an isolated incident and women and girls continue to be kidnapped on a regular basis. Even if they escape, many face stigmatization in their communities.

UNHCR is the lead organization in providing protection and assistance to refugees and displaced populations in the region of Diffa. However, the interest of donors is waning.

In January 2018, UNHCR launched a regional Appeal seeking US$157 million to respond to the needs of refugees displaced by Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin – comprising Niger, Chad and Cameroon. By the end of July, just 32 per cent of the required funding had been received.

In the Diffa region, UNHCR works with partner organizations, as well as with community-based protection groups to enhance prevention of SGBV, and to ensure access to adequate response services, including medical, psychosocial, economic and legal support. But with underfunding in the protection sector, this assistance does not reach everyone.

“We need to recognize SGBV as a crime and a gross violation against the well-being, freedom and integrity of a person,” emphasizes Morelli.

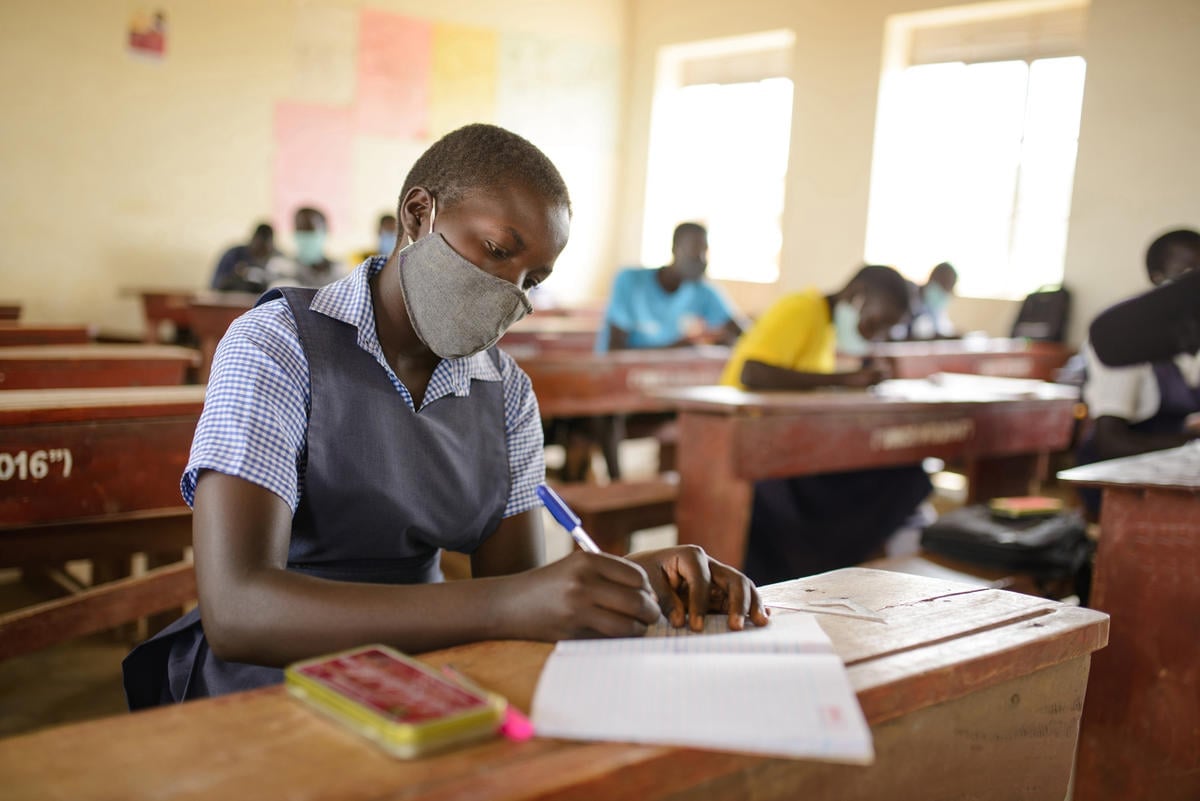

UNHCR is seeking appropriate solutions for Adia. They start with moving her to the refugee camp where she will have access to basic services, including education and a range of support services, and also include the possibility of resettling her to a third country – help she urgently needs.

As Adia left us, her tiny frame sagged under the weight of the baby she carried on her back, as well as the weight of all that she has endured.

*Name changed to protect the identity of the survivor