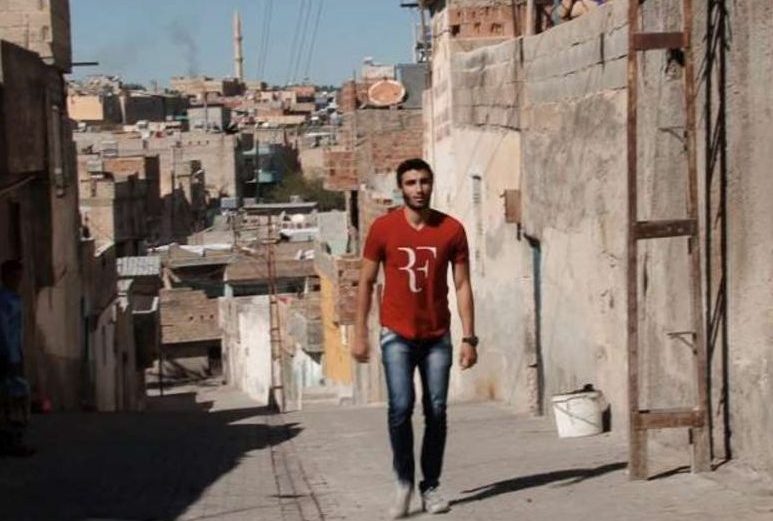

22 October 2013, Three years ago, Abdul Rahman was an athletics champion and a university law student with a bright future. Today, he can still sail high and far as a long jumper, but there are no sports prizes on offer and he can’t find a job. For his family, that is a disaster.

Since fleeing with his family 10 months ago, the Syrian has been living as an urban refugee in the southern Turkey city of Urfa. An older brother, Mazen, was shot in the neck in the conflict and paralyzed. Abdul and the seven other members of the family take turns tending him in a rundown apartment in the winding streets of the ancient city.

With his sports background, Abdul Rahman at first found work in a sports centre. His US$250 monthly salary covered the rent and left a little for food for the family. Then he lost his job. For weeks he has done the rounds of markets and companies and shops, looking for any sort of work.

During his months in Urfa he has also studied Turkish, and now speaks it quite well. “They [potential employers] ask me what I can do, and then they ask if I am Syrian,” he said. “If you’re Syrian, there is no job. They tell me to leave my phone number and they will get in touch.”

Abdul Rahman is just one of an underground population of Syrians living in the old city. Some 46,000 have been registered by the Turkish authorities, who estimate there may be at least another 20,000 unregistered urban refugees. That combined total is more than 10 per cent of Urfa’s population. Across Turkey there are 200,000 Syrian refugees in camps but more than 460,000 urban refugees, according to the government.

The UNHCR is trying to help speed up the process of registration by providing 23 mobile registration and coordination centres. Registration is important as it opens up access to many rights. Once registered, refugees assistance and an identity card allowing them free medical care.

“When we came, the Turkish people were very generous,” Abdul Rahman said. “The family had nothing but the clothes on our back. God be praised, they helped us.”

But what he has noticed – a pulling back, a new reluctance to help or offer work – is confirmed by international officials. Local organizations and local NGOs were very generous when the first refugees came but, as the flow shows no signs of slowing, there is donor fatigue.

For Abdul Rahman and his family, the problem will soon become acute. With only one of four brothers and a cousin working now – there are eight in the family in Urfa – there isn’t enough money.

The eldest brother, Hazim, explains: “What we earn here in Turkey is not enough to pay the rent, furniture for the house, daily expenses. We don’t make enough. It’s the same problem we faced in Syria, there isn’t enough to get to the end of the month.”

The family has an added financial burden – the medical care for Mazen. A therapist, a Syrian refugee himself, comes regularly to massage and manipulate his withered limbs, but the family must find the money for most medication.

And winter is coming, which means increasing electricity bills. The family has one large electric heater. “In Syria we say that summer is for the poor, while winter is for the rich,” Abdul Rahman noted.

Many Syrians in Urfa fear the winter and dream of home. But Abdul Rahman thinks of staying, of using his rapidly improving Turkish to enter university and start studying sport and physical fitness. Not a dream of flight, but of putting down roots in a country that war chose for him.