UNHCR report calls for action to support millions of young refugees living in some of the world’s most vulnerable communities.

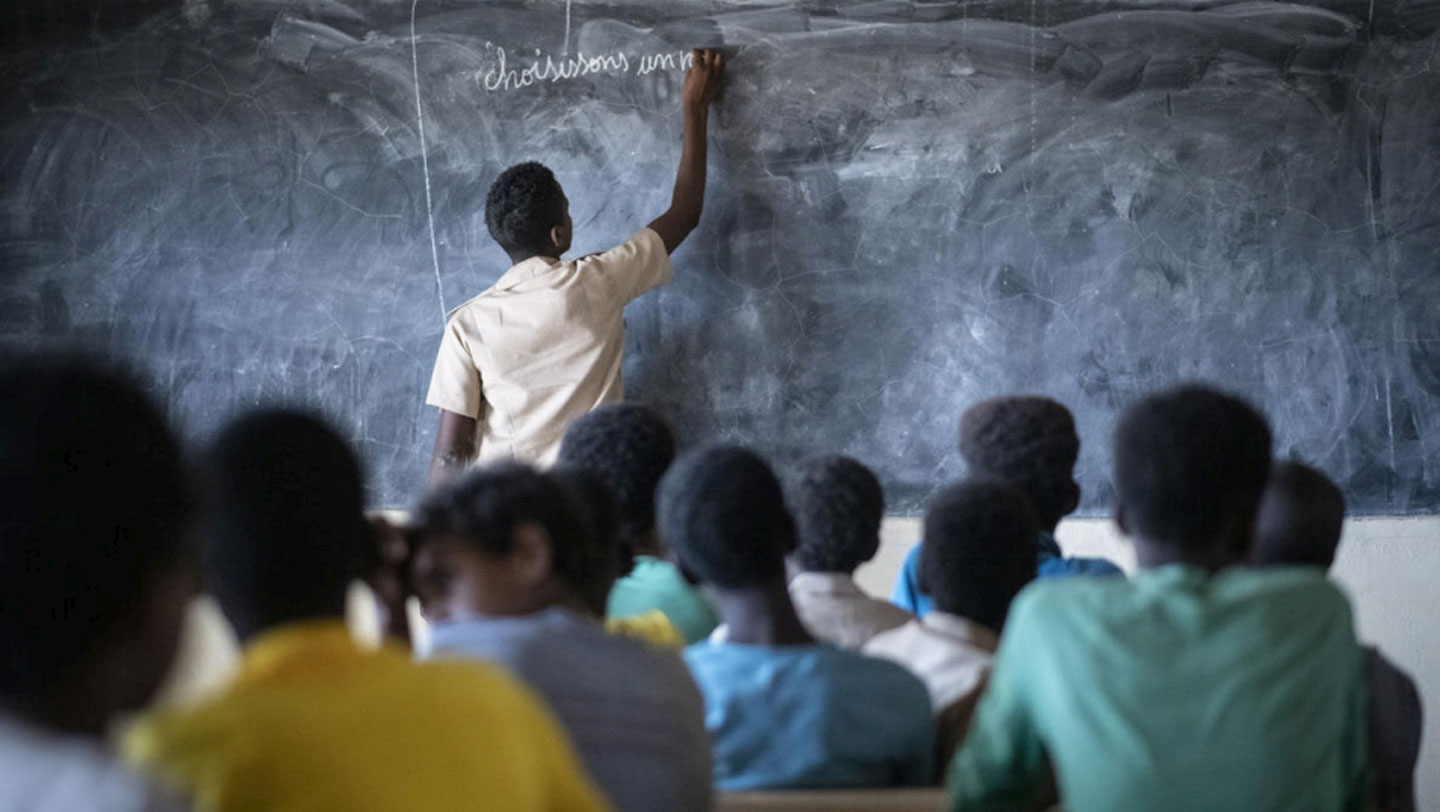

© A Malian refugee student plays the role of teacher at a school in Goudoubo camp. Because of rising insecurity teachers no longer show up and students often teach each other. © UNHCR/Sylvain Cherkaoui

GENEVA – COVID-19 presents a dire threat to refugee education worldwide, according to a hard-hitting report issued today by the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR.

The report “Coming Together for Refugee Education” notes that half of all refugee children are out of school and calls for immediate and bold action by the international community to beat back the catastrophic effects of the coronavirus.

“We cannot rob them of their futures.”

“Half of the world’s refugee children were already out of school,” says Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

“After everything they have endured, we cannot rob them of their futures by denying them an education today. Despite the enormous challenges posed by the pandemic, with greater international support to refugees and their host communities, we can expand innovative ways to protect the critical gains made in refugee education over the past years.”

The report details that, while children in every country have struggled with the impact of COVID-19, refugee children have been particularly disadvantaged. UN figures show that 1.6 billion learners across the world, including millions of refugees, have had their education disrupted.

Before the pandemic, a refugee child was twice as likely to be out of school as a non-refugee child. This is set to worsen – many may not have opportunities to resume their studies due to school closures, difficulties affording fees, uniforms or books, lack of access to technologies or because they are being required to work to support their families.

However, the report also highlights a series of inspiring examples of how young refugees and their teachers have kept going through the pandemic.

“From refugees and host communities to teachers, private sector partners, national and local authorities, innovators and humanitarian agencies … all have found numerous ways to keep education going in the face of the pandemic. It has been a demonstration of partnership, generosity, and creative thinking, allied to the passion and determination of millions of young people,” Grandi says.

During lockdown, refugees and teachers, governments, UNHCR’s partners, all came up with various resourceful ways to keep education going. They ranged from Egypt moving its entire curriculum online, to a teacher in Dadaab refugee camp broadcasting lessons over a local radio station.

Also included were mobile classrooms in Bolivia, new roles for parent-teacher associations in Chad, and a learning content platform in Uganda that has found a way around the obstacle of low or no connectivity.

The report states that without greater support, steady, hard-won increases in school, university, and technical and vocational education enrolment could be reversed – in some cases permanently – potentially jeopardizing efforts to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 4 of ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education for all.

In a powerful Final Word to the report, the Vodafone Foundation and UNHCR Ambassador for the Instant Network Schools Programme, Mohamed Salah, said: “Ensuring quality education today means less poverty and suffering tomorrow. Unless everyone plays their part, generations of children – millions of them in some of the world’s poorest regions – will face a bleak future. But if we work as a team, as one, we can give them the chance they deserve to have a dignified future. Let’s not miss this opportunity.”

Adapting to the limitations imposed by COVID-19 has been especially tough for the 85 per cent of the world’s refugees who live in developing or least developed countries. Mobile phones, tablets, laptops, good connectivity, cheap or even limitless data, even radio sets … these are often not readily available to displaced communities.

“I am especially concerned with the impact on refugee girls.”

The 2019 data in the report is based on reporting from 12 countries hosting more than half of the world’s refugee children. While there is 77% gross enrolment in primary school, only 31% of youth are enrolled in secondary school. At the level of higher education, only 3% of refugee youth are enrolled.

Far behind global averages, these statistics nevertheless represent progress. Enrolment in secondary education rose, with tens of thousands of refugee children newly attending school; a 2% increase in 2019 alone. However, the pandemic threatens to undo this and other crucial advances. For refugee girls, the threat is particularly grave.

Based on UNHCR data, the Malala Fund has estimated that as a result of COVID-19, half of all refugee girls in secondary school will not return when classrooms reopen this month. For countries where refugee girls’ gross secondary enrolment was already less than 10%, all girls are at risk of dropping out for good – a chilling prediction that would have an impact for generations to come.

“I am especially concerned with the impact on refugee girls. Not only is education a human right, but the protection and economic benefits to refugee girls, their families, and their communities of education are clear. The international community simply cannot afford to fail to provide them with the opportunities that come through education,” says Grandi.

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter