CHAPTER 2:

SECONDARY EDUCATION

LOST FUTURES

Somali girls share a joke during class at Ifo secondary school in Dadaab refugee camp, Kenya, home to more than 200,000 refugees. Since 2016, a total of 572 students have accessed higher education, representing just 13 per cent of eligible post-secondary students. © UNHCR/VANIA TURNER

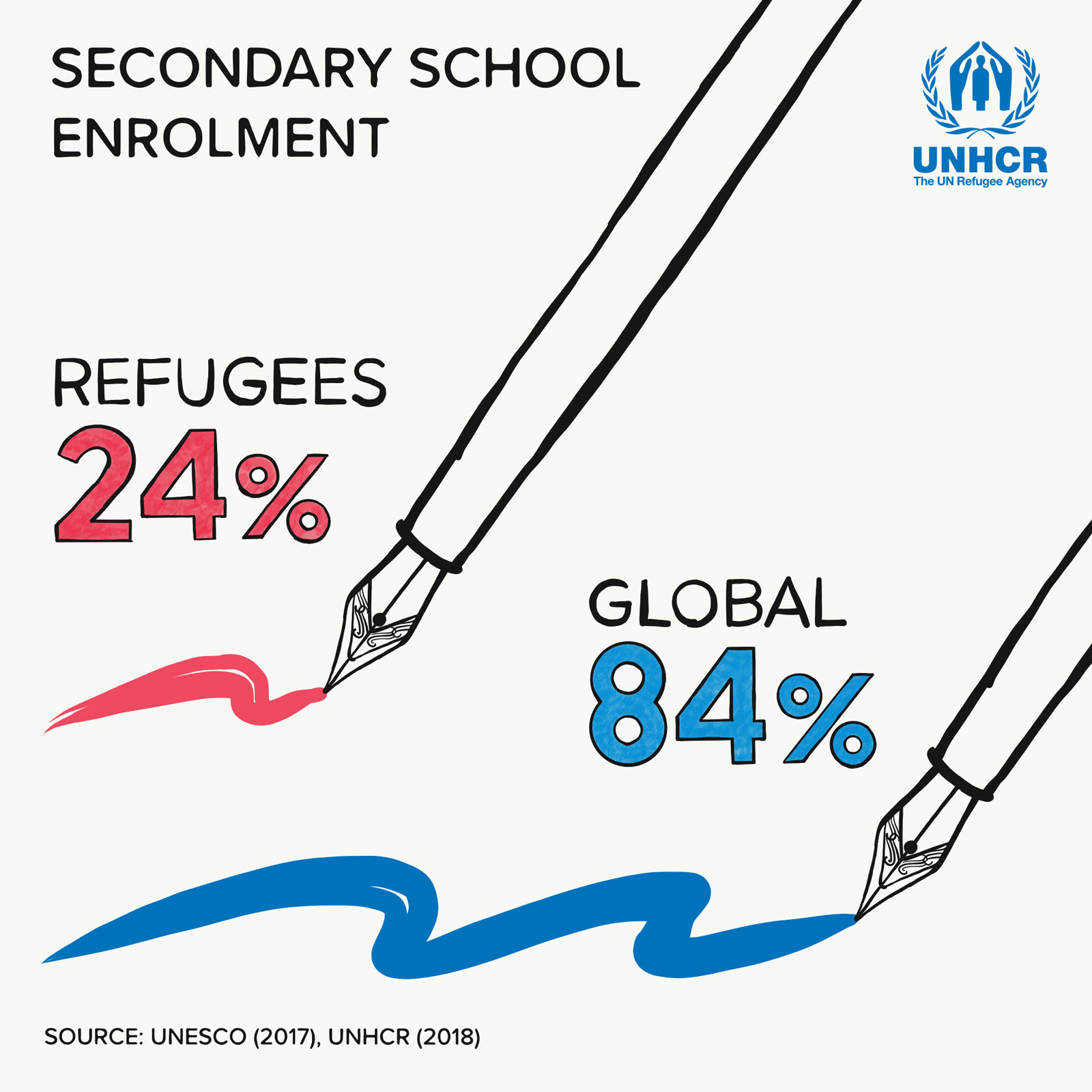

As each year passes, the likelihood of a refugee child progressing to the next academic grade drops sharply. That continual fall in enrolment is true of primary school, but the effect is especially marked in the transition to secondary. While close to two-thirds of refugee children are enrolled in primary education, less than one-quarter of refugee adolescents make it to secondary. Put this next to the global average of 84 per cent, and it is immediately clear that refugee adolescents are at a huge disadvantage as they strive to take the next step on their educational journey.

Given that secondary school is the gateway to further education and improved employment opportunities, this deals a crushing blow to a young refugee’s dreams of a brighter future. Progress in this area has been painfully slow: secondary enrolment for refugees rose by just one percentage point in 2018, to 24 per cent. Yet this rise, modest though it may seem, does still represent tens of thousands of new places in the classroom for refugees. Every single effort by host governments, donors, UNHCR and partners can transform a child’s life.

Competing demands, tougher choices

A big part of the problem is the sheer lack of secondary schools in many refugee-hosting areas, making the transition from primary a practical impossibility. Where schools do exist, getting into them can already be a challenge for local youth in developing regions, so the addition of hundreds or thousands of new arrivals only intensifies competition for classroom space.

The shortfall in physical infrastructure is evident in Kakuma refugee camp, in northern Kenya, which has one of the sharpest drops in enrolment from primary to secondary – a phenomenon that affects children from the host community as well as refugees. There are only seven secondary schools in the region, compared to 26 primaries. Even those who pass primary examinations with flying colours can find they have reached the end of their school careers. The worst case is in Bangladesh, where less than one per cent of refugee youth in the two formal Rohingya refugee camps set up in the early 1990s have access to a formal lower secondary education. The rest – including the majority of those who fled their homes since August 2017 – must make do with a limited access to informal education without any form of accreditation.

There are many reasons for the shortage but at the heart of the problem is the simple fact that secondary education costs more than primary. Subject learning at secondary level is more advanced, with some subjects requiring significantly better facilities and learning materials. In addition, secondary studies demand better qualified teachers. The right teacher equipped with the right tools can make a child positive and enthusiastic about the school day; conversely, poor teaching and supervision can be highly demotivating, which, when added to myriad other pressures at this age, leads to high dropout rates.

Dalal Assah, 18, a Syrian refugee, graduated top of her class from her secondary school in Za’atari refugee camp, Jordan. Dalal dreams of studying English at university. © UNHCR/MOHAMMAD HAWARI

These financial demands have an impact not just on education ministries and local authorities, who must find the necessary funding, but on refugee families as well. As they grow up, refugee adolescents come under greater pressure to support their households. In this regard, girls are often at an even greater disadvantage in terms of “opportunity costs” – perceived losses in terms of income and domestic duties. Collecting water or fuel, taking care of younger siblings or older relatives, and carrying out household chores are all tasks that fall heavily on girls. Such domestic contributions are often seen as more valuable than any investment in their education. As they reach adolescence, girls can face added pressures to give up educational ambitions so that they can marry early or start earning an income instead. If a refugee family has limited resources and must choose which siblings can continue with their education, boys are often prioritized because they are seen as having the greater earning potential.

Some of the costs are slightly more disguised but no less real. For instance, longer distances to and from the school gates make reaching school more expensive and, in areas of instability, potentially more dangerous. And in some regions, refugees have limitations placed on their freedom of movement, preventing them from going to schools that are far from their homes.

All these pressures are magnified if the educational “pathway” is unclear. For many refugees, becoming a teenager is also the moment where the educational journey comes to an end. If there is no hope of continuing one’s studies much beyond primary, families are more likely to question the usefulness of sending their children to secondary school.

Secondary education plays a crucial role in the protection of young refugees when they are at a particularly vulnerable age. If they have nothing to occupy their day and no clear employment prospects, adolescents are more vulnerable to exploitation and more likely to turn to illegal activities out of desperation.

Karox Pishwan (right), now 18, arrived in Serbia from Irbil, northern Iraq, as an unaccompanied child. He is doing his homework with the help of tutors at the Jovan Jovanovic Zmaj home for children in Belgrade. © UNHCR/DANIEL ETTER

Give girls a chance

For girls, the risks of being excluded from school can be particularly grave – but the rewards of an education can be huge.

Education reduces girls’ vulnerability to exploitation, sexual and gender-based violence, teenage pregnancy and child marriage. According to UNESCO, if all girls completed primary school, child marriage would fall by 14 per cent. If they all finished secondary school, it would plummet by 64 per cent. Other UNESCO research shows that one additional year of school can increase a girl’s earnings by up to a fifth – bringing benefits for the girls themselves, their future families and their communities. Just as importantly, the further girls progress with their schooling, the more they develop leadership skills, entrepreneurship and self-reliance – personal qualities that will help their communities flourish as they strive to adapt to their host countries or as they rebuild their own homes.

Young Afghan refugee students attend a photography course at the Technical and Vocational Training Organization (TVTO) in Mashhad, Iran. © UNHCR/ANDREW MCCONNELL

A refugee girl’s time in exile should, therefore, be considered an excellent opportunity. So it is a travesty that, globally, at secondary level there are only about seven refugee girls for every 10 refugee boys enrolled. According to a World Bank report, limited educational opportunities for girls and barriers to completing 12 years of education are costing countries between US$15 trillion and US$30 trillion in lost lifetime productivity and earnings[1].

A vital ingredient in improving these statistics is increasing the numbers of female teachers. For girls, a lack of female teachers can spell the end of their secondary education as parents in some conservative communities will not allow their daughters to be taught by a man. Female teachers also help girls to feel more comfortable in the classroom, especially should they need to report incidents of sexual harassment or abuse. Most important of all, a female role model can inspire and support girls to complete their studies – and even motivate them to become teachers themselves.

But the gender gap is not only present among students: the number of female teachers in schools teaching refugees decreases between pre-primary and secondary education. For example, in Chad 98 per cent of teachers in pre-primary are female, but at secondary school this figure drops drastically to only 7 per cent.

© UNHCR/ NESTOR HEINDAYE

“I remember, during my first and last year of high school, I had a great biology teacher. She was very dedicated and made me love science”, says Nassima Hissein Abdelalaziz, 29, from Central African Republic. But war interrupted Nassima’s life and almost put an end to her dreams of becoming a doctor.

In December 2013, she and her mother had to flee to Chad when she was in her fifth year of medical school. Thanks to the support of UNHCR and encouragement from her mother, Nassima was able to resume her studies at the medical faculty of the University of N’Djamena. She is currently in her 7th year and is busy preparing her final doctoral dissertation.

“Now that I am at university, I actually have 10 female professors, which is about one quarter of all professors. It is so inspiring,” she said.

Closing the gap

With secondary education in such a depleted state, including refugee children in national education systems must be central to all efforts to improve the picture.

By developing inclusive systems in which refugees and their non-refugee peers learn side by side, education ministries and their supporters are building durable, long-term resources. These could serve generations of students, whether during refugee emergencies, protracted situations or after refugees have returned home, settled elsewhere or integrated into their host countries.

Increasing secondary school provision has a significant “multiplier effect” as it potentially benefits millions of local children as well as refugees. In north-eastern Mozambique, for example, the government’s decision to build Maratane school, next to the camp of the same name, will mean that both the local community and refugees will have access to secondary education for the first time. Demand is expected to soar when the school is finally equipped and up and running, with spaces allocated for up to 500 refugees.

Kedro Sahane Yusuf (left), 17, Fartun Sahane (centre), 18, and Ikra Mohammed Abdul (right), 19, Somali refugees, in class at Dicac Secondary School in Bokolmanyo, Ethiopia. © UNHCR/GEORGINA GOODWIN

In order to include refugees in their plans for secondary education, national education ministries need the requisite resources – material, technical and financial. That means reliable, multi-year funding to ensure education systems are equipped to handle both local and refugee children.

As of January 2019, UNHCR offices in more than 20 African countries were collaborating with national education authorities, other UN agencies and civil society organizations to support refugee inclusion in education sector planning, such as by advising on providing education in emergency refugee situations. To make real and long-lasting progress, every country that hosts refugees should follow this lead.

But funding is also required to support refugee families who would otherwise rely on financial support from their teenagers, and thus to enable them to take full advantage of secondary school opportunities that come their way. The cost of tuition, exam fees, uniforms, learning materials and transport can all act as deterrents, so reducing or eliminating these costs removes those barriers. Cash transfers not only give families the ability to prioritize what they need (and benefit the local economy to boot), they also reduce the likelihood of their turning to child labour and forced marriage as ways of finding an income. They have improved access, attendance and participation in schools in a range of countries, including Kenya, Turkey, Chad and Egypt. In the latter case, a project implemented by Catholic Relief Services that is tied to proof of enrolment and attendance – but with no restrictions on how the money is spent – has helped improve refugee children’s school attendance, particularly at secondary level.

© UNHCR/ADRIENNE SURPRENANT

Prince-Bonheur, 22, and his cousin Gothier, 23, grew up together in Mougoumba, Central African Republic, but conflict separated them in 2013. Prince crossed the Ubangui River and made it to Boyabo refugee camp in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, while Gothier jumped onto the nearest boat and floated down towards Betou in the Republic of Congo.

Like most children their age who flee conflict, a lack of secondary schools, teachers and education materials in the camp meant neither of them would be able to continue their studies.

“Losing five years of schooling has taken me so many steps back,” said Gothier. “But that’s the only way I can restart my life. Education is the key.” He was finally able to return home in 2018, when UNHCR assisted the government with the voluntary return of nearly 4,500 Central Africans in the Congo to the Lobaye region. He enrolled in secondary school and is now doing his best to catch up on everything he missed.

Prince, however, hasn’t been able to return to Mougoumba and remains a refugee in DRC.

“Ever since I left home five years ago, I haven’t been to school. I stay idle, without studying.”

As more Central Africans return from exile, the country will need money to build and expand schools, train more teachers and supply additional learning materials.

To support such projects and policies and close the yawning gap in opportunity, UNHCR is in the process of setting up a new initiative dedicated to improving secondary education prospects for refugee children and youth. Named the Secondary Youth Education Programme, it is aimed at increasing school enrolment and at boosting retention and completion of secondary education. It has been successfully piloted on a small scale since 2017 in Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda and Pakistan and will significantly expand in the coming years. UNHCR is working with education ministries to identify the main factors that have been shown to support the successful transition from primary to secondary school, particularly for girls. These include placing advisors within education ministries, increasing the number of female teachers, building and refurbishing infrastructure, and providing cash directly to households, allowing them to cover the cost of sending their children to school.

Children have the right to a full education cycle. With inclusion at the heart of national policymaking, proper planning, reliable funding and engagement with both refugee and host communities, the stubborn barriers to secondary school can finally be broken down – opening new routes to higher education.

CASE STUDY: BANGLADESH

Young Rohingya refugees strive to keep dreams of an education alive

Most Rohingya children have no access to education at all, but are prepared to overcome almost any obstacle for even the smallest opportunity to learn

Shehana, 16, a Rohingya refugee in Bangladesh, attends the Diamond Adolescent Club, but longs to be admitted back into formal education. © UNHCR/IFFATH YEASMINE

They don’t have desks or chairs. But in a bamboo-built room decorated with posters and paintings, 30 female Rohingya teenagers aged 15 and older are sitting on the ground, bent forward and writing intently into their workbooks, as a mathematics formula is posted on a blackboard.

These are some of the lucky ones. Few girls are able to continue their studies once they reach adolescence. In addition, there are only a small number of temporary learning centres in the sprawling refugee settlements in south-eastern Bangladesh that provide any learning opportunities at all for children over 15.

Some 55 per cent of refugees in the Rohingya settlements are under 18. All are barred from following the Bangladesh national curriculum.

Shehana, a bright but shy 16-year-old, knows she is better off than many, but still longs to be admitted back into formal education. She is one of the girls studying in the bamboo hut, known as the Diamond Adolescent Club, set up by UNHCR’s partner CODEC nearly two years ago.

“Back in Myanmar, I was in grade 6. I wanted to be a teacher and to be able to go to college. I love teaching. And I’m happy to be here,” she said.

“We learn new things almost every day. I think I’m lucky, but I try to tell others why education is important and to convince them to let girls study – how it can help with better opportunities in the future. Some of our relatives have listened to me and they now send their daughters to school.”

Shehana comes from a family where education has always been highly prized. Her brother, Mohammed Sharif, 17, studies at the same adolescent club with other boys in the afternoon, while one of her older sisters, 21-year-old Jannat Ara, teaches children aged four to five at a home-based learning centre, bringing along her own five-year-old daughter.

It soon becomes clear where this passion for education comes from. Shehana’s father, Nur Alam, 43, was a former senior teacher at a school of around 450 pupils in Maungdaw, in Myanmar’s Rakhine State.

When the family fled the violence in Myanmar two years ago and arrived at Kutupalong refugee site, Nur Alam volunteered to teach youngsters at a mosque set up in the settlement. He picks up his phone and shows me a photo of his former students – a group of boys and girls – at his old school.

“I feel like crying when I see this,” he said. “I miss my students very much. Many of my old students who completed grade 6 are in the camp here. Many have positions as volunteers working with organizations in the camp… when they see me, they greet me. They tell me that because they listened and learned, it helped them get these opportunities and they are better off now.”

Younger children can take part in informal learning activities, with learning centres offering three shifts a day and providing instruction in English, maths, Myanmar language and life skills.

This learning stream is not linked to any government curriculum, however, nor is there yet age-appropriate education for older students — even for those who were enrolled in school in Myanmar before they fled to Bangladesh.

Shortages of qualified teachers are another problem, despite efforts by UNHCR, sister agencies and partners to boost teacher training.

The net result of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya children in Bangladesh being barred from following the national curriculum is that the Sustainable Development Goal 4, to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” is not being reached.

“The education system in the settlements is not really focused on proper education, but more on keeping children busy and safe,” said Nur Alam.

CASE STUDY: DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

Top of his class and hungry for more, a young refugee battles the odds

On the run from South Sudan’s civil war, a boy named Gift is determined to continue his education. But his ingenuity, brilliance and determination may not be enough to keep him in school.

Gift, 14, a South Sudanese refugee, is top of his class in Uboko primary school in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. But lack of places in secondary schools mean he may not be able to continue his education. © UNHCR/JOHN WESSELS

Gift, 14, has been top of his class for the past three years. That may not be enough to keep him in school.

“When I grow up, I would like to become a teacher. I would like this job because I like to help those who have less knowledge,” he said of the ambition that has driven him forward against the odds.

Those odds were considerable. Gift fled the war that was ravaging his homeland, South Sudan, a conflict that had claimed the life of his father. Determined to succeed, he learned French from scratch and even designed his own light from spare parts of a broken solar lamp so he could study at night.

Despite all his hard work, a huge cloud hangs over Gift’s future. The talented teenager is in his last year of primary school in the eastern stretches of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) where secondary school places are few and far between.

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, helps refugee children such as Gift go to school by providing cash grants that help families to pay fees, and to purchase schoolbooks, supplies and uniforms. But both funds and opportunities are limited, particularly at secondary school level, which means Gift and thousands of other South Sudanese child refugees may have to call a premature halt to their studies.

Gift and his uncle – who became his legal guardian after his father was killed and he lost touch with his mother – sought safety in Biringi settlement, in the DRC, in 2016.

The boy well remembers his first day in Uboko primary school, where 800 local Congolese and refugee children study together after the school was rehabilitated by UNHCR. He was excited and thankful for a new opportunity to learn again.

“The war makes a lot of people suffer – I had to quit school because of the war. When I found out I was going back to school, it made me happy,” he recalled with a smile.

Mastering French, the main language of instruction in the DRC, was achieved by attending language courses provided by UNHCR – with Gift even winning a province-wide spelling contest.

Then he had a practical problem: no electricity meant he had no light by which to study at home at night. His solution? To design his own solar-powered lamp. “I had to build this,” he said, holding out a flimsy light made of three bulbs and a solar battery held together by tape.

As South Sudanese children continue to seek refuge in Congolese territory, the education gap is only increasing. Only 4,400 out of 12,500 South Sudanese children in the DRC have access even to primary education. Until recently, they had no secondary opportunities whatsoever.

In 2019, UNHCR started a small programme to enrol refugees in secondary school. It also helps to construct and refurbish school buildings.

Even so, of the more than 6,000 South Sudanese secondary-age refugees, a staggering 92 per cent still do not go to school.

Gift knows the odds are stacked against him. And he fears he will be regarded as worthless in the eyes of both his host community and his fellow refugees if he cannot get an education. It is vital to both his hopes of becoming a teacher, he says, and of becoming a voice for others in his position.

Yet he simply cannot imagine life without education. “It would be horrible if I couldn’t go to secondary school,” he said. “There should be a way for everyone to study.”

Ann Encontre, UNHCR’s Regional Representative in the DRC, said there are “extraordinary talents” among the young refugees she has met. “When you talk to them, you see how eager they are to learn.”

Secondary school gives refugee adolescents a sense of purpose, a vision of the person they can become, and the knowledge that will one day help them rebuild their homes, she adds.

“The alternative to school is waiting around with no clear options for the future. This is why we are doing all we can to keep them in school.”