‘I promise, from this moment on, things will get better’

UNHCR’s Salome Ayukuru, widely known as ‘Mama’, has been helping vulnerable refugees to rebuild their shattered lives for nearly two decades.Photos and text by Giles Duley in Bidibidi, Uganda

19 August 2020

‘I promise, from this moment on, things will get better’

UNHCR’s Salome Ayukuru, widely known as ‘Mama’, has been helping vulnerable refugees to rebuild their shattered lives for nearly two decades.

Photos and text by Giles Duley in Bidibidi, Uganda

19 August 2020

Salome Ayukuru has lost track of how many refugees she has interviewed.

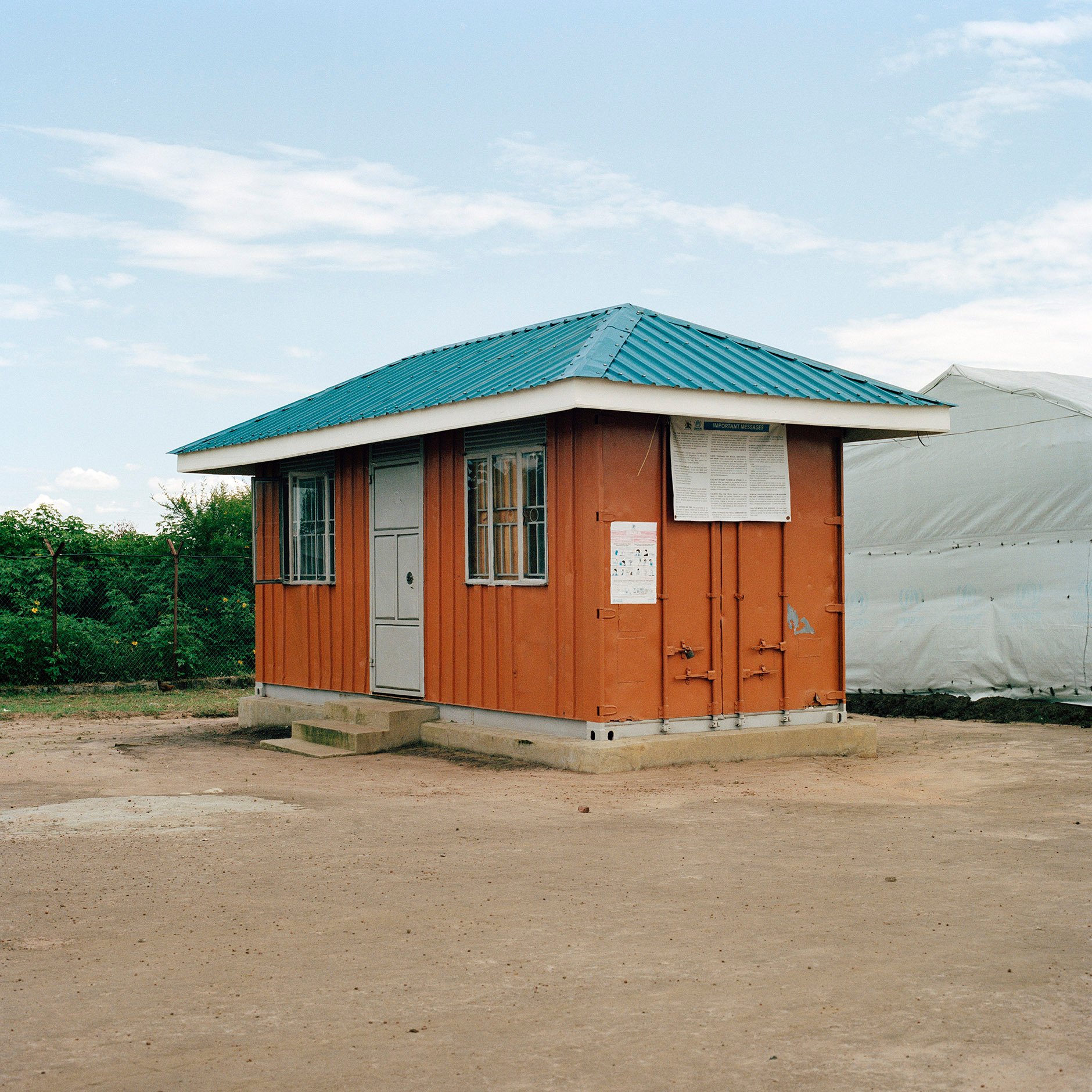

After nearly 20 years working for UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, she estimates it is in the thousands. Yet, each time she sits in her small portacabin office at a transit centre between the Ugandan border and the Bidibidi refugee settlement, she gives her undivided attention to the person sitting across from her.

This time, it is three young siblings from South Sudan.

They tell Salome that when their father died, their mother remarried a man from a different tribe who refused to accept them. Their mother started beating them and shouting at them, hoping they would leave. When that didn’t work, she told them to go to a refugee camp in Uganda where their late father’s family was living. She promised to join them there later. When they arrived at the border, there were no relatives to meet them and they had no way to contact their mother.

Salome Ayukuru has lost track of how many refugees she has interviewed.

After nearly 20 years working for UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, she estimates it is in the thousands. Yet, each time she sits in her small portacabin office at a transit centre between the Ugandan border and the Bidibidi refugee settlement, she gives her undivided attention to the person sitting across from her.

This time, it is three young siblings from South Sudan.

They tell Salome that when their father died, their mother remarried a man from a different tribe who refused to accept them. Their mother started beating them and shouting at them, hoping they would leave. When that didn’t work, she told them to go to a refugee camp in Uganda where their late father’s family was living. She promised to join them there later. When they arrived at the border, there were no relatives to meet them and they had no way to contact their mother.

“There are good people here who will give you a good home.”

“First, we need to place you with a family that will look after you. There are good people here who will give you a good home,” says Salome. “I promise you, the worst is over.”

As she speaks, it is Nyoko, 12, whose expression indicates that she has just comprehended their situation – that her mother lied and is not coming for them; that they have been abandoned. Her sister, Bagia, 10, senses something is wrong but does not yet fully understand, while eight-year-old David is busy pulling faces and amusing himself.

As a UNHCR protection officer in Arua, in northern Uganda, Salome is the first point of contact for the most vulnerable South Sudanese refugees after they cross the border into Uganda. For many of them, it is their first moment of safety and the first time they can tell their stories.

“This is not therapy; we are just talking.”

“This is not therapy; we are just talking. But this conversation is vital as the first stage in rebuilding lives,” Salome explains later. “They have given up on life, but when we talk, that is when they realize that yes, a terrible thing has happened, but somebody cares.”

The 61-year-old Ugandan has a gift for making people feel they are being listened to. Her manner is gentle and caring, but firm. She explains that it is important the refugees understand their situation and the realities they face, as it is only then that she can help them adjust and get the support they need.

After their interview with Salome, the three siblings move on to the next stage of the intake process. They will be registered and given a hot meal, medical checks, and vaccinations before being transferred to Bidibidi, Uganda’s largest refugee settlement.

“There are good people here who will give you a good home.”

“First, we need to place you with a family that will look after you. There are good people here who will give you a good home,” says Salome. “I promise you, the worst is over.”

As she speaks, it is Nyoko, 12, whose expression indicates that she has just comprehended their situation – that her mother lied and is not coming for them; that they have been abandoned. Her sister, Bagia, 10, senses something is wrong but does not yet fully understand, while eight-year-old David is busy pulling faces and amusing himself.

As a UNHCR protection officer in Arua, in northern Uganda, Salome is the first point of contact for the most vulnerable South Sudanese refugees after they cross the border into Uganda. For many of them, it is their first moment of safety and the first time they can tell their stories.

“This is not therapy; we are just talking.”

“This is not therapy; we are just talking. But this conversation is vital as the first stage in rebuilding lives,” Salome explains later. “They have given up on life, but when we talk, that is when they realize that yes, a terrible thing has happened, but somebody cares.”

The 61-year-old Ugandan has a gift for making people feel they are being listened to. Her manner is gentle and caring, but firm. She explains that it is important the refugees understand their situation and the realities they face, as it is only then that she can help them adjust and get the support they need.

After their interview with Salome, the three siblings move on to the next stage of the intake process. They will be registered and given a hot meal, medical checks, and vaccinations before being transferred to Bidibidi, Uganda’s largest refugee settlement.

Since 2013, when South Sudan’s civil war erupted, nearly four million people have been forcibly displaced – more than half of whom have sought safety in neighbouring countries. About 80 per cent of those displaced are women and children.

Most of the refugees Salome interviews are children who have lost contact with their parents and single mothers with babies. Cut off from their families and communities in a new country, they often struggle to cope and can become depressed or even suicidal.

Salome understands this better than most. When she was 18, rebel fighters in Uganda killed her father and then tortured her. In a reverse of the current situation, she fled to what is now South Sudan and lived in a refugee camp there for six years.

“If you find a solution, you can make good out of bad.”

“When I was a refugee, what was going to kill me was loneliness. To be with no family, no common language – it can kill many refugees,” she says. “I know what it is to be so lonely, because I’ve experienced it.”

Even after losing her home and family, Salome’s focus was always on others. She adopted an abandoned baby in the refugee camp and brought her up as her own. She now supports over 30 children, many of them Ugandan street children. Some of them have gone on to become nurses and teachers.

“If you find a solution, you can make good out of bad,” says Salome, who is known to everyone here as ‘Mama’.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdown initially affected Salome’s work, making it difficult for her and other staff to go to the refugee settlements and the border area. She resorted to making daily calls to refugee leaders to follow up on people with the most pressing needs.

“When I would call, what came out was that our absence was strongly felt and that we needed to be there to help find solutions to the refugees’ challenges,” she explains. “They were frustrated and feeling isolated and that pained me very much.”

Throughout her day, Salome sits through one harrowing story after another. Yet, after their time with her, the refugees leave with some hope. They are directed towards the specialized help they need whether it is psychological support, adult education, foster care, food, clothing or training on how to build a shelter. It is the start of the long process of rebuilding their shattered lives.

Since 2013, when South Sudan’s civil war erupted, nearly four million people have been forcibly displaced – more than half of whom have sought safety in neighbouring countries. About 80 per cent of those displaced are women and children.

Most of the refugees Salome interviews are children who have lost contact with their parents and single mothers with babies. Cut off from their families and communities in a new country, they often struggle to cope and can become depressed or even suicidal.

Salome understands this better than most. When she was 18, rebel fighters in Uganda killed her father and then tortured her. In a reverse of the current situation, she fled to what is now South Sudan and lived in a refugee camp there for six years.

“If you find a solution, you can make good out of bad.”

“When I was a refugee, what was going to kill me was loneliness. To be with no family, no common language – it can kill many refugees,” she says. “I know what it is to be so lonely, because I’ve experienced it.”

Even after losing her home and family, Salome’s focus was always on others. She adopted an abandoned baby in the refugee camp and brought her up as her own. She now supports over 30 children, many of them Ugandan street children. Some of them have gone on to become nurses and teachers.

“If you find a solution, you can make good out of bad,” says Salome, who is known to everyone here as ‘Mama’.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdown initially affected Salome’s work, making it difficult for her and other staff to go to the refugee settlements and the border area. She resorted to making daily calls to refugee leaders to follow up on people with the most pressing needs.

“When I would call, what came out was that our absence was strongly felt and that we needed to be there to help find solutions to the refugees’ challenges,” she explains. “They were frustrated and feeling isolated and that pained me very much.”

Throughout her day, Salome sits through one harrowing story after another. Yet, after their time with her, the refugees leave with some hope. They are directed towards the specialized help they need whether it is psychological support, adult education, foster care, food, clothing or training on how to build a shelter. It is the start of the long process of rebuilding their shattered lives.

“We have to protect the very serious cases, and they are many. So I can’t give up.”

It took Salome a long time to recover from her own experiences as a refugee. At the time, there was far less support available than there is now. What drives her is making sure the most vulnerable refugees are protected. Such dedication takes a toll, but she refuses to give up.

“We have to protect the very serious cases, and they are many. So I can’t give up,” she says.

Her next interviewee is Sandra, an orphan who is unsure of her age. All she knows is that she had just had her period for the second time when a soldier raped her on her way to the local shop. She did not tell her foster family, and when she discovered a few months later that she was pregnant, tensions with the family grew.

Soon after she gave birth, they asked her to leave. She went looking for the soldier who had raped her, but when she found him, he threatened to kill her. Fearing for her life, she walked to the border with her baby.

Sandra now sits across from Salome, her baby wrapped in blankets on her lap.

“We have to think of the practical now,” Salome tells her. “I know you are strong. You wouldn’t have made it here with your child if you weren’t. We will get you a protection officer to look after your case. We will find you a place in the camp for you to live. You will get food, we will get some clothes for the baby…”

She pauses and looks at Sandra. “Do you love your baby?” she asks.

Sandra looks down at the floor and doesn’t answer.

“Okay, let me put it another way – if you could, would you leave the child with me?”

Sandra nods without looking up.

“Sandra, you will learn to love this child,” says Salome. “You must learn to love it, because if you don’t, this child will never accept love. You have to break the cycle.

“What happened to you is not right, it should never have happened. But it does happen, it happens to many, so know you are not alone. I promise from this moment on, things will get better.”

“The first thing we have to do is remind these girls that they are still alive.”

As Sandra gets up to leave, Salome stops her.

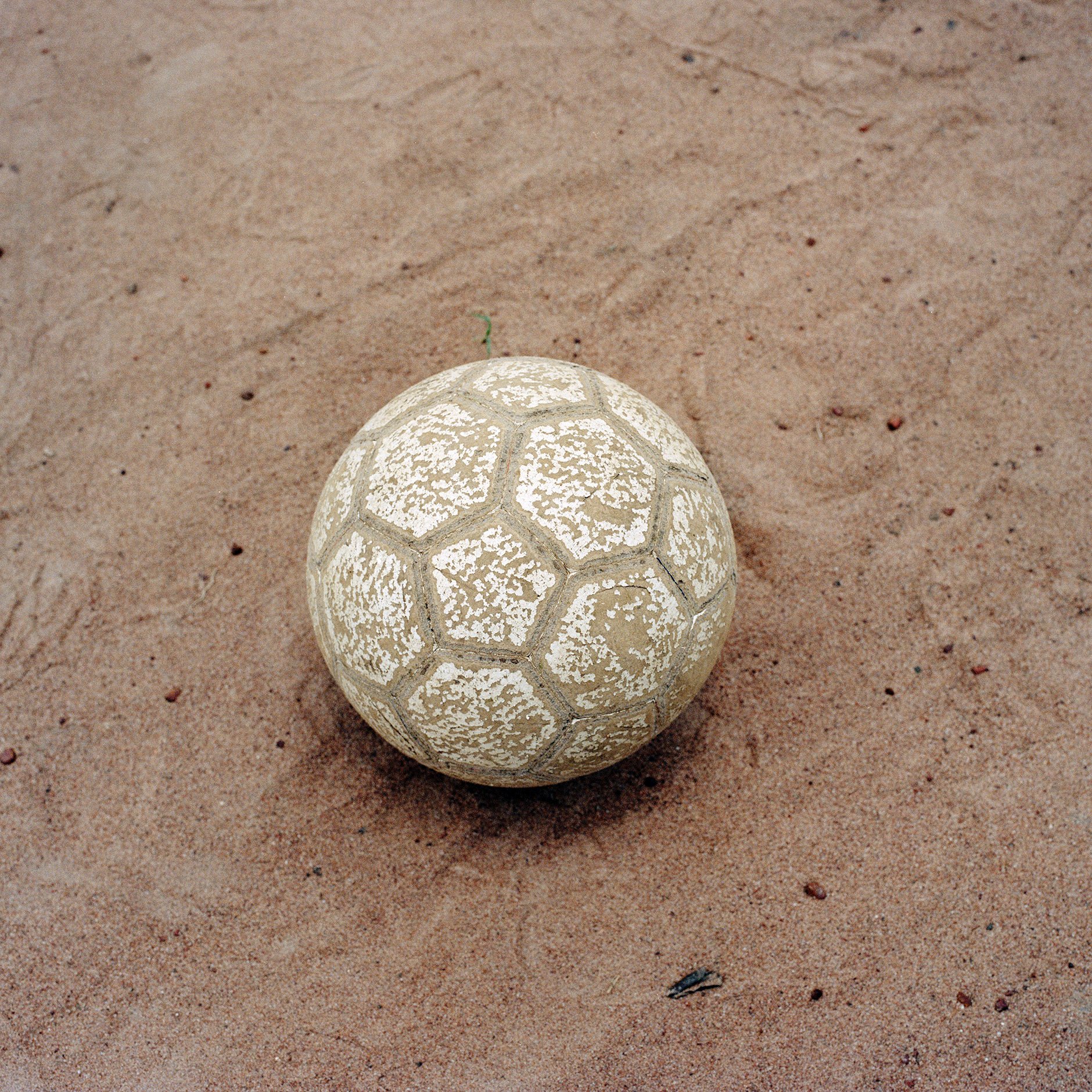

“You see those girls playing netball out there? I want you to go over there. There are lots of older women around. Ask one of them to hold your child, they will be happy to. Then play with the girls for a while,” she says.

Salome watches Sandra as she walks towards the field. She may have seen 1,000 children like her, but it is clear that each of their stories stays with her.

“The first thing we have to do is remind these girls that they are still alive,” she says.

With additional reporting by Catherine Wachiaya.

Parts of this story were reported before the closure of Uganda’s borders in March 2020, following the country’s measures to contain the spread of COVID-19. The transit centre at the border is now temporarily closed.

“We have to protect the very serious cases, and they are many. So I can’t give up.”

It took Salome a long time to recover from her own experiences as a refugee. At the time, there was far less support available than there is now. What drives her is making sure the most vulnerable refugees are protected. Such dedication takes a toll, but she refuses to give up.

“We have to protect the very serious cases, and they are many. So I can’t give up,” she says.

Her next interviewee is Sandra, an orphan who is unsure of her age. All she knows is that she had just had her period for the second time when a soldier raped her on her way to the local shop. She did not tell her foster family, and when she discovered a few months later that she was pregnant, tensions with the family grew.

Soon after she gave birth, they asked her to leave. She went looking for the soldier who had raped her, but when she found him, he threatened to kill her. Fearing for her life, she walked to the border with her baby.

Sandra now sits across from Salome, her baby wrapped in blankets on her lap.

“We have to think of the practical now,” Salome tells her. “I know you are strong. You wouldn’t have made it here with your child if you weren’t. We will get you a protection officer to look after your case. We will find you a place in the camp for you to live. You will get food, we will get some clothes for the baby…”

She pauses and looks at Sandra. “Do you love your baby?” she asks.

Sandra looks down at the floor and doesn’t answer.

“Okay, let me put it another way – if you could, would you leave the child with me?”

Sandra nods without looking up.

“Sandra, you will learn to love this child,” says Salome. “You must learn to love it, because if you don’t, this child will never accept love. You have to break the cycle.

“What happened to you is not right, it should never have happened. But it does happen, it happens to many, so know you are not alone. I promise from this moment on, things will get better.”

“The first thing we have to do is remind these girls that they are still alive.”

As Sandra gets up to leave, Salome stops her.

“You see those girls playing netball out there? I want you to go over there. There are lots of older women around. Ask one of them to hold your child, they will be happy to. Then play with the girls for a while,” she says.

Salome watches Sandra as she walks towards the field. She may have seen 1,000 children like her, but it is clear that each of their stories stays with her.

“The first thing we have to do is remind these girls that they are still alive,” she says.

With additional reporting by Catherine Wachiaya.

Parts of this story were reported before the closure of Uganda’s borders in March 2020, following the country’s measures to contain the spread of COVID-19. The transit centre at the border is now temporarily closed.

To support UNHCR’s work with people fleeing violence in South Sudan, donate now.