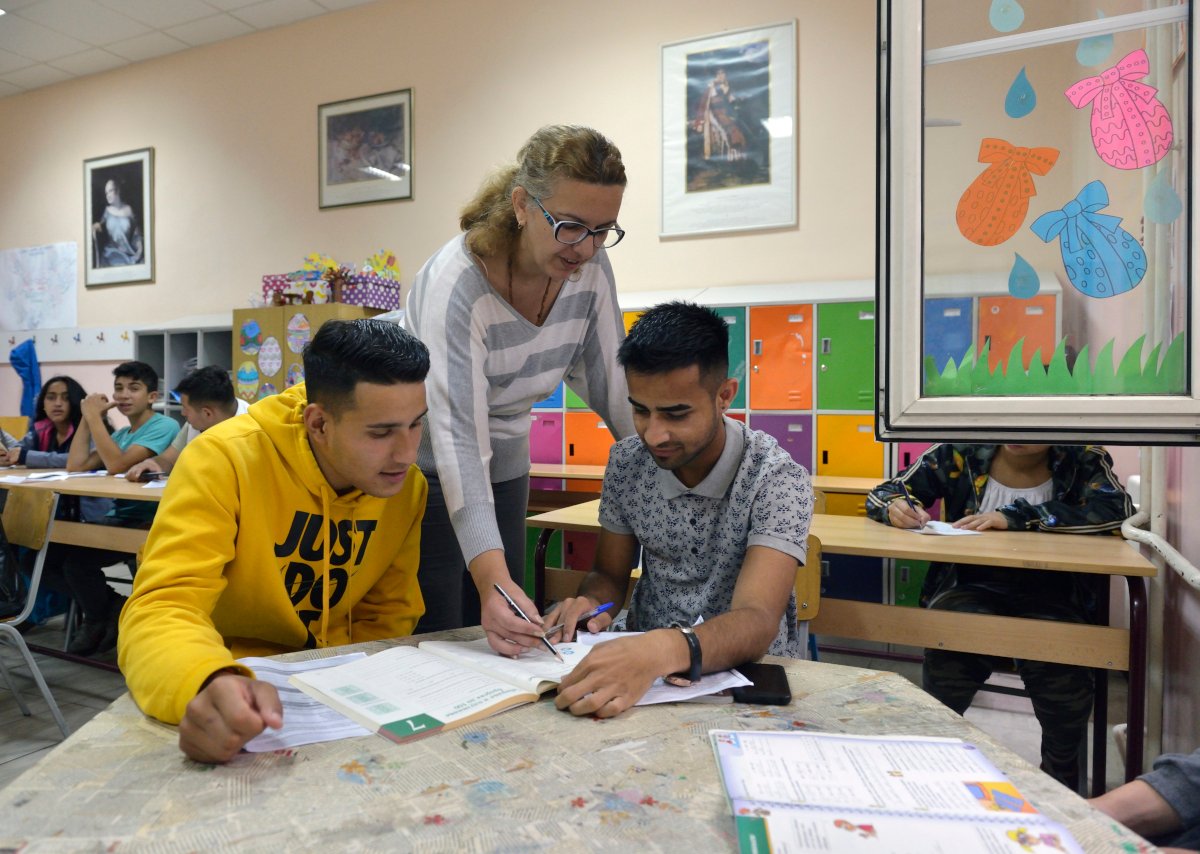

Mustafa Samoi Kabul, Afganistan 17 . Years ( yellow blouse ) and his frend Mohammead Ibrahim Noori , Afganistan 17. year. Refugee children in the Serbian school Primary school Branko Pesic, Zemun. Belgrade 06.05.2019 ©UNHCR Serbia/2018/Shubuckl

Firash and Asadi* are taking their school leavers’ exams. “It’s a bit stressful, yeah, but that’s normal,” says Firash. “It’s good,” says Asadi. “I will get the documents I need to prove I am educated.” For these two young asylum seekers from Afghanistan, Serbia has provided the stability they needed to finish their education.

One school in particular — Branko Pešić Elementary School — has played a key role in helping not only these two lads but some 300 refugees and migrants since 2016. Indeed, the school has done such valuable, pioneering work to integrate refugees into the mainstream curriculum that its principal, Nenad Ćirić, has been nominated this year for UNHCR’s prestigious Nansen Award.

“The worst thing that can happen to a child is to be confined to a place with no activities, nothing to challenge the mind,” says Mr. Ćirić, explaining why he took refugees out of their asylum centres and included them alongside Serbian kids in his school. “We were painfully aware that they (the refugee youngsters) were in no way to blame for what was happening in their countries.”

He had the blessing of the Ministry of Education to lead the way in this, as he and his staff had considerable experience dealing with marginalised children, including Roma. The Branko Pesić model is now used as a basis for national guidelines for inclusion of refugee children and has been rolled out to other schools in towns with refugees.

Serbia is hosting some 3,600 new refugees, migrants and asylum seekers and around 400 children among them are attending mainstream schools. “Until recently, many refugees perceived Serbia only as a transit country,” says UNHCR’s representative in Serbia, Hans Schodder. “Nevertheless, Serbia has achieved comprehensive enrolment of school-age refugee children and developed innovative methods to support them.”

At Branko Pešić, teachers sacrificed their summer holidays to brainstorm ideas for adapting the curriculum to meet the needs of refugees, the majority of whom were unaccompanied Afghan minors. UNHCR began bussing the youngsters into school from their accommodation at the Krnjača asylum centre.

“At first, these kids had no notion of the Serbian language,” says Mr. Ćirić. “Usually it is only the children of diplomats who are in that position. In addition, we did not have methods for teaching Serbian as a foreign language. These had to be developed.”

Farsi and Arabic-speaking interpreters, paid by ADRA, began working in the classrooms, translating subjects such as geography and history, while extra Serbian lessons were arranged to give the refugees intensive language training.

With maths, it was a bit easier. Says maths teacher Dušica Marsenić: “Maths is a specific language that you can recognise, provided you have some education.”

The problem was that some 30 per cent of the refugee children had had no education at all in their home countries and were illiterate in their mother tongues. In some cases, they learnt to read and write for the first time in Serbian.

“We had youngsters who had travelled 5,000 km to reach Serbia,” says Mr. Ćirić, “but they didn’t know the points of the compass.” To avoid humiliating the teenagers, staff placed them not with small kids but in higher classes and gave them maximum individual attention.

Illiteracy was not an issue for either Firash or Asadi but frustration and disappointment were psychological barriers to initial progress. Both had been trying to reach Western Europe and were pushed back to Serbia from Croatia and Hungary respectively.

“I was sad, confused and tired,” says Firash.

“I was feeling bad, feeling unlucky,” says Asadi.

Asadi has family in Germany and has not given up hope of joining them eventually. But Firash, responding to his teachers’ investment of time and energy in him, has applied for asylum in Serbia and hopes to settle in Belgrade.

He came from Kabul, where his father was a policeman, making the family vulnerable to threats from the Taliban. He reached Serbia two years ago after a rough journey through Iran, Turkey and Bulgaria.

“When I started at this school,” he says, “honestly I didn’t understand anything and I was just passing the time. But I saw it could be good to learn Serbian and I made an effort. Now I am starting to get something out of it. I can speak, understand and help myself.”

Firash, who has had a guardian under a UNHCR scheme, is living at the Jovan Jovanović Zmaj Home for Children (of the City Centre for Social Work). He earns some money by working at a car wash and an Arab fast-food restaurant. He hopes to go into hairdressing while also perhaps studying languages.

But he is afraid his asylum application may be rejected and he will no longer be able to continue his education. “Others will choose for me,” he says apprehensively.

What if he had a choice himself? “My choice is clear,” he says. “I want to live in Belgrade, one hundred per cent.”

*Names have been changed for identity protection

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter