This historical tradition of accepting refugees in the Philippines offers a new perspective on the development of the country as a safe haven for families escaping conflict and violence.

Filipinos are hospitable by nature, and wherever you go in the world you can find a Filipino community welcoming you into their homes and serving you their version of adobo. In the Philippines, a booming tourism industry has harkened more than 20 million tourists to visit the country in the past year alone with the promise that it’s “More Fun in The Philippines.”

Earlier than the Philippines’ invitation for foreign nationals to visit the country’s beaches and islands, Filipinos have opened up their hearts and homes to refugees fleeing war and persecution in their home countries.

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, has long lauded the Philippines for its strong humanitarian tradition.

“I have served with UNHCR in many countries, each with their own protection needs. What makes Filipinos special is that they seem to naturally and intuitively understand and empathize with people who have been uprooted from their homes by war, conflict, violence, persecution, and calamities,” says Yasser Saad, UNHCR Philippines’ Head of Office.

“In my three years here, I have noted that Filipinos—the man on the street, in government, in the military, in courts, in businesses—are some of the most compassionate people whose actions for the vulnerable and the displaced go beyond the bare minimum. At a time when expressions of solidarity are becoming rare, at a time when inward-looking, security-focused policies become dominant, Filipinos remains a beacon of hope and humanitarian spirit,” Mr. Saad added.

Such tradition was recently manifested in May 2015, when 300 Rohingya fled Myanmar and drifted afloat in sea after being pushed back in their attempts to seek refuge in neighbouring shores, one country, the Philippines, expressed its willingness to take them in.

This historical tradition of accepting refugees in the Philippines offers a new perspective on the development of the country as a country of asylum for refugees.

The First Wave of White Russians

At the end of World War I, a first wave of 800 “White Russians” came to the Philippines fleeing persecution from “Red Russians” or supporters of the Socialist Revolution of 1917.

The 800 Russians were part of a larger fleet of 7,000 to 8,000 refugees who fled one of the last military strongholds of the White Russians, Vladivostok City. Twenty-three ships departed the city in October 1922 and wandered the sea looking for a safe port of call. After Japanese-ruled Korea denied them safe passage, the fleet split up between the last two safe ports of call: Shanghai, China and Manila, Philippines, with others leaving for Manchuria.

Eventually, the refugees were resettled in countries such as the United States or stayed in the Philippines. U.S. Governor-General to the Philippines Leonard Wood rallied the U.S. Government to accept 526 refugees in San Francisco. The rest of the 800 refugees left for Australia or stayed in Manila or other far-flung areas in the Philippines. Two hundred and fifty of them migrated to Mindanao to work in then-prospering abaca plantations.

Jewish Refugees fleeing Nazi persecution

This paved the way to the admittance of the second wave of refugees: European Jews escaping Nazi persecution in World War II. One thousand two hundred Jewish refugees fled to the Philippines under the admittance of President Manuel L. Quezon and U.S. High Commissioner Paul V. McNutt in 1934.

President Quezon pushed back against critics of his open-door immigration policy by issuing Proclamation No. 173 on August 21, 1937. He called on all Filipinos to welcome the refugees and instructed the government to assist them. President Quezon offered up his land in Marikina for the refugees, and pushed to admit up to 30,000 Jewish refugees fleeing persecution.

This second wave later became the basis of President Quezon’s issuance of Commonwealth Act 613, later the Philippine Immigration Act of 1940.

President Quezon working together with McNutt, Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower and Jewish American cigar manufacturer Herbert Frieder rallied together to grant the refugees work visas to escape the horrors of Nazi-led Germany. A pillar of the Jewish community in the Philippines, the Frieder brothers helped raise money to support Jewish refugees during their stay in the country. Jewish refugees were able to find sanctuary in the Philippines before Filipinos and Jews alike experienced the brunt of the Second World War.

A monument in President Quezon’s honor was erected in Tel Aviv, Israel, inscribed with his words of welcome for refugees, that: “the people of the Philippines will have in the future every reason to be glad that when the time of need came, their country was willing to extend a hand of welcome.”

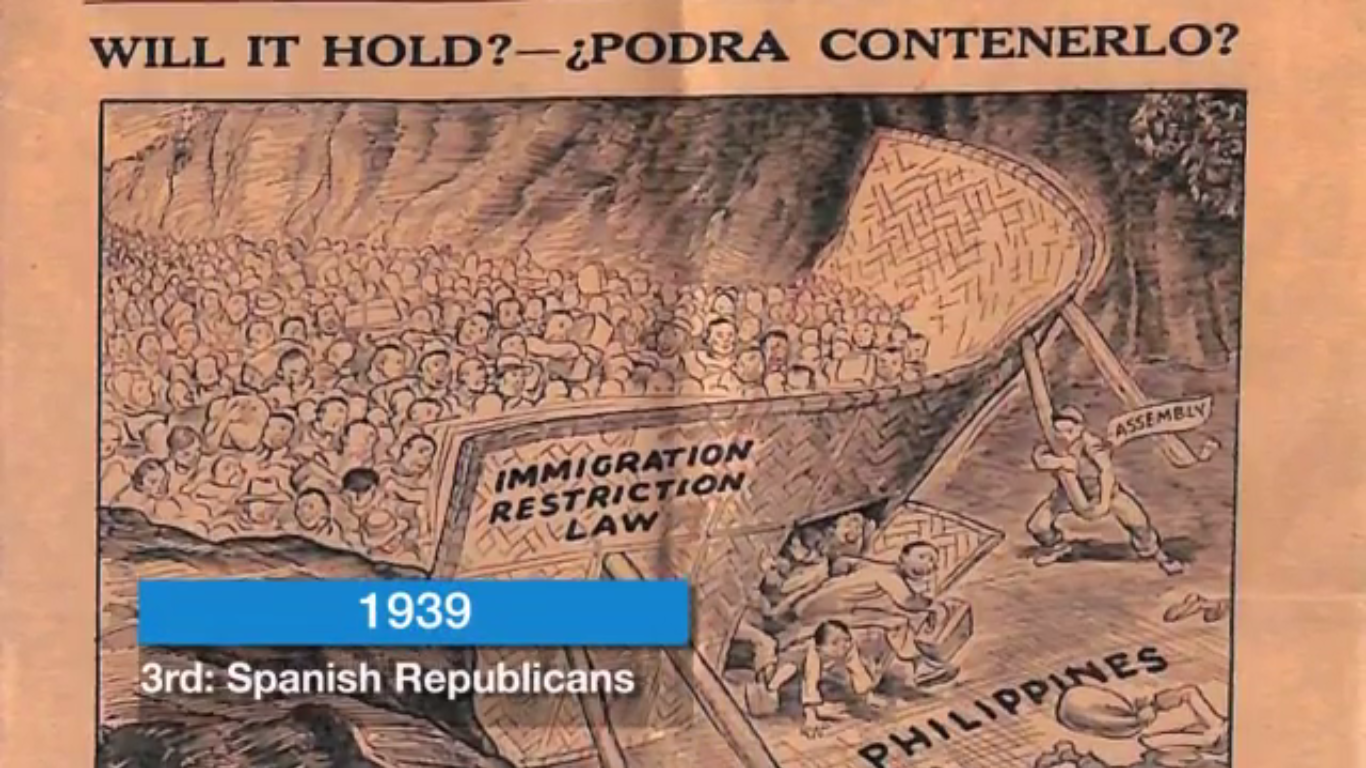

Spanish Republicans flee new Nationalist Government

In 1939, Spanish republicans fleeing the end of the Spanish Civil War entered as the third wave of refugees, benefitting from the Philippine government’s policy of absolute neutrality.

Prior to the end of the war, President Quezon had stressed the importance of absolute neutrality in the war to the public. In a letter dated November 10, 1937 to the Rector of San Juan de Letran College, Quezon urged that the Philippines’ interest in the war should be limited to seeing peace reestablished in Spain. Support for President Quezon’s policy came from loyalists to the Spanish Republic, several religious orders and the local Spanish community.

From 1936 to 1939, Spanish Republicans had fled from the fascist Falange Española of General Francisco Franco. Head of the Nationalist movement, General Franco was cracking down on Republicans in Spain forcing 500,000 Spanish Republicans and their families to flee the country for France and North Africa to avoid incarceration or death. From France, refugees struggled to obtain visas to other countries. Among the few countries who did grant them visas were former Spanish territories such as Mexico, the Dominican Republic and the Philippines.

Chinese refugees escape from the mainland

The succeeding year, Chinese immigrants sought refuge after the Chinese Civil War, wishing to evade the grasp of the newly-formed communist People’s Republic of China. Filipinos welcomed some 30,000 Kuomintang members fleeing the mainland.

In the same year, the Philippine Congress enacted the Philippine Immigration Act of 1940. The law limited the annual number of immigrants to 500, but allowed the President the discretion to admit refugees for “religious, political or racial reasons.”

This definition of who is a refugee was echoed in the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, to which the Philippines became a signatory to. This provision also proved to be instrumental as the Philippines saw an increase in the number of refugees seeking asylum in the Philippines.

Notably during this period, the Philippines gained full sovereignty and its Constitution allowed the naturalization of Chinese immigrants and other foreign nationals. Philippine-born children of Chinese immigrants could now become full-fledged Filipino citizens with their parent’s naturalization.

The Time of the White Russians

Then came the “Tiempo Ruso” (Time of the Russians): a second wave of 6,000 White Russians were welcomed under President Elpidio Quirino.

The White Russian community in Shanghai, China were wary of approaching communist forces to the city and sent out a letter asking for refuge to countries across the world. Only the Philippines replied and granted their request.

It was an important act that called for a regime for the international protection of refugees. The White Russians who settled in the Philippines set a precedent for the amendment of the Displaced Persons Act of 1948. The Philippines stood out as the only nation who expressed willingness to accept them even while the young republic was still reeling from the havoc of war.

Similar to the Chinese refugees that came before them, the White Russians sought to escape Communist rule in China and found refuge in the camp set up in Tubabao Island, Guiuan, Eastern Samar, from 1949 to 1953.

A former receiving station for the United States Naval Base, Tubabao Island (formerly Camparang) was home to 6,000 refugees. The camp itself was run by the International Refugee Organization, the predecessor of UNHCR, but manned by the elated White Russians who took to the island life and looked at its inhabitants with joy and relief.

A mix of different nationalities from the former Soviet Union (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics), the White Russians were Russian, Armenians, Estonians, Germans and Austrians, Turko Tatars, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Czechs and Yugoslavs, Polish, Latvians, and Hungarians.

The White Russians taught the locals piano and ballet, and, according to local tradition, served as the choir for Catholic masses in the Immaculate Conception Church of Guiuan. In exchange, the people of Guiuan allowed the refugees to hold Orthodox Masses in the church.

After staying for about four years, the refugees were resettled in 12 countries, including Australia, US, Brazil, Dominican Republic, France and Belgium.

The years following the resettlement of the White Russians, refugees escaping conflict from neighboring countries in Asia and in the Middle East would seek refuge on Philippine shores.

Vietnamese “boat people” arrive on Philippine shores

From 1975 to 1992, Vietnamese “boat people” or refugees fleeing the Vietnam War and reunification of the North and South Vietnam made up the sixth wave.

Fearing repercussions for supporting the fallen South Vietnam Government and their American allies, refugees fled in droves after the fall of Saigon. Their boats would drift aimlessly at sea before being brought by the current to foreign countries.

Several boats washed up on the shores of northern Philippines and refugees were initially rescued by fishermen and families living along the coasts of Bataan.

In total, 2,700 refugees were admitted and lived in the refugee processing centers in Ulugan Bay and Tara Island, Palawan where they were allowed to work, farm and fish.

Prohibited from working outside the camp, most of the refugees opted to relocate to other countries, like Canada. Some refugees who had families or had fell in love and married Filipinos chose to stay in the country, establishing a little Vietnam known as the local tourist site Viet Ville on the site of the former refugee camp.

Iranian Revolutions aftermath leave refugees stateless

At the close of the 1970s, the seventh wave arrived after the Iranian Revolution forced several thousands of Iranians studying and working in Manila to seek refugee status in the Philippines rather than go home to a new government that took over by force and violence.

Tensions remained high among students loyal to different factions of the Revolution, but fighting was kept at bay by the Philippine’ officials warning of deportation. Several Iranian refugees have opted to remain in the Philippines, integrating into the local Muslim community or marrying Filipinos and seeking Philippine citizenship. By the 1990s, the Philippine census reported that Iranians made up the largest population of non Indo-Chinese refugees.

Indo-Chinese neighbors flee regime changes

Starting in 1980, the eight wave was made up of nationals from other Asian countries escaping regime changes in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. To accommodate the refugees, the Philippine Refugee Processing Center in Morong, Bataan was opened.

UNHCR worked with the Philippine government to shelter, train and ready the refugees for their new lives once relocated to foreign shores. Refugees were encouraged to attend classes to learn English as well as other education programs.

A total of 400,000 Indo-Chinese refugees escaped in boats to the Philippines from 1980 to 1994. Refugees were admitted into the country to be processed for relocation to other countries that expressed willingness to admit them, like the US, Canada, France and Australia.

East Timorese refugees flee during struggle for Independence

In 2000, a ninth wave was made up of East Timorese given temporary protection during their country’s struggle for independence from Indonesia.

Some 600 refugees from the Philippines’ South Asian neighbor took refuge in the country during the struggle.

Former President Estrada supported local fundraising efforts to support the refugees. The Catholic Church in Manila raised 200,000 dollars for the cause.

After security was restored, the refugees in Philippines, Indonesia and other countries were repatriated to East Timor.

Following this long tradition of offering asylum to refugees forced to flee their countries from war, conflict, and persecution, history looks on fondly on the Philippines’ goodwill towards asylum seekers.

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter