In 2016, Norway contributed with USD 118 million to UNHCR globally, thereby becoming UNHCR’s largest donor in relation to the population size of the country and the seventh largest donor overall. In 2016, Norway was also UNHCR´s largest donor of unearmarked core support per capita, granting UNHCR flexibility and means to allocate resources wherever urgent or unforeseen needs erupted.

Norway has a large donor focus on the devastating Syria crisis, including generous funding for resettlement initiatives and for providing quality and protective education to refugee children. Norway has been contributing to UNHCR’s Education Strategy 2012-2016 in 11 countries, among them being Lebanon, where the need is extremely high. In 2016, Norway contributed with USD 1,2 million to UNHCR’s Education Strategy in Uganda and Iran. By supporting education in emergency situations, Norway contributes to addressing both immediate humanitarian needs and long term development goals.

UNHCR and education for Syrian refugees

When the brutal war erupted in Syria in 2011, 1,5 million people fled to neighboring Lebanon, 470,000 of which were children aged between 3 and 17. About 155,000 Syrian refugee children were enrolled in the 2015 school year. The remainder, more than 235,000, are unable to attend school because of the limited capacity of public schools. Some families are not capable of affording additional costs like transportation, while the financial situation of others are so strained that the children need to work. Many children are also dealing with the psychological consequences of trauma caused by conflict and displacement.

The drop-out rate in Lebanon is estimated to be significant, with various factors contributing to children failing to complete primary and secondary education. The factors include difficulties of reintegrating back into formal education after losing critical years of education due to displacement; difficulties related to language as the curriculum in Syria is in Arabic while it is bilingual (English or French and Arabic) in Lebanon; prohibitive associated costs; low interest in education due to limited future opportunities, which are just some of the obstacles refugee children face in Lebanon.

As the number of Syrian refugee students grew in 2013, the Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE) and UNHCR worked together to open an afternoon shift, or the so-called “second shift” to accommodate students who could no longer attend the regular morning shift. Second shift classes now take place from 2 pm until 6 pm, and are especially set up for Syrian refugee students.

The initiative, which aimed to help Lebanon’s public schools accommodate the thousands of young new guests was made possible with the help of UNHCR, Norway, and other partner organisations.

Zeina dreams of becoming a doctor

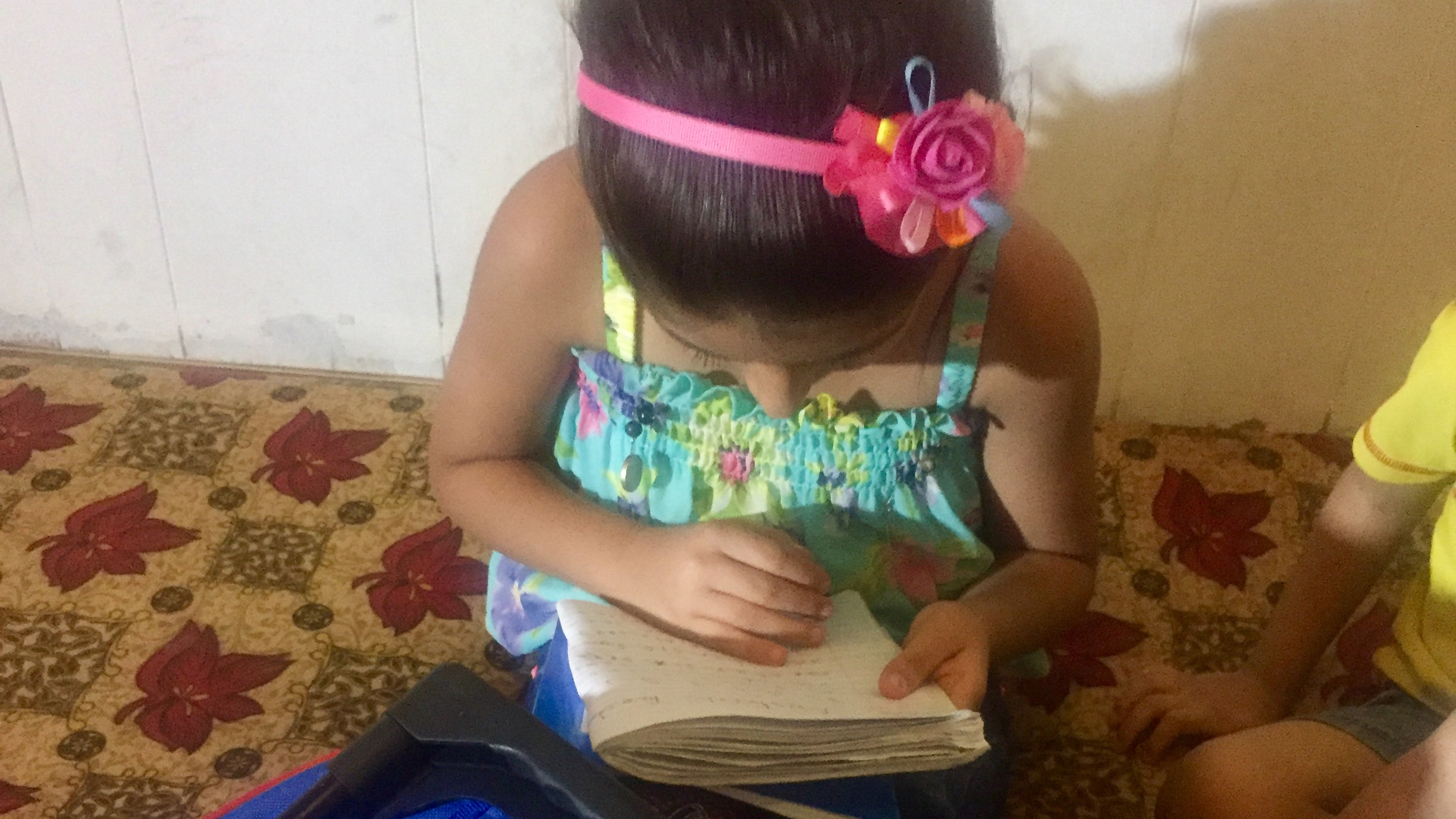

In Sidon, which is about 40 kilometers south of the capital Beirut, seven-year-old Zeina* wakes up at 6 am, even though her classes do not begin until 2 pm. She braided her hair, got dressed, and wore her special pink head band on that sunny October morning. She continued to go over her notes and check her school supplies, making sure that everything was in order for her first day back to school.

“She’s so happy to start school again,”

– Zeina’s mother, Mona

Because of daily heavy shelling, Zeina, along with her parents, two younger brothers and younger sister fled from the Syrian town of Homs in 2012. The air strikes were so severe that young Zeina would faint from fear whenever the explosions were too loud or too close.

Zeina and her younger sister Laila are among the lucky refugee children in Lebanon. Even though they are poor and live in a shabby, empty, old apartment with barely any furniture or any proper beds, Zeina and her sister attend Sidon’s intermediate public school, free of charge. Laila attends the early shift which ends at 1.45 pm and Zeina attends the so-called ‘second shift’ from 2 pm to 6 pm.

As the principal rings the first school bell of the year, dozens of excited Syrian refugee children storm through the gates of Sidon’s intermediate public school. With big smiles, and even bigger backpacks, the young students rush to queue up, waiting for their names to be called as teachers direct them to their new classrooms. As Zeina stands happily in line, her mother, Mona looks on.

“The most important thing for me is for my children to get an education,” Mona says. “This is their weapon so that they can be self-sufficient and independent in the future. I can’t read or write. If I was educated I would be working now. I wouldn’t be here.”

Zeina’s enrollment fees, school supplies, and even after school homework assistance is all paid for by MEHE, UNHCR and international donors such as Norway.

“She wants to become a doctor when she grows up and God willing she will be. Her grades are very good.”

Protection through education: Investing in durable solutions

UNHCR’s education intervention in Lebanon, with the help of Norway, aims to support Lebanon’s Ministry of Education and Higher Education’s plan to provide access to primary education for everyone in public schools. This is done by providing financial support through the transfer of funds to MEHE to cover tuition fees for refugee children. The initiative also provides a massive Back to School campaign with UNICEF and other partners.

Despite massive challenges and high dropout rates, education officials in Lebanon are optimistic. They say the system is slowly improving and expanding. In the 2015 academic year, 238 public schools were opened with a second shift from 2 pm to 6 pm, compared with 144 schools in the previous year and 89 the year before that.

Soumaya Hneineh, from the Lebanon Ministry of Education, says that this education initiative means more Syrian refugee children are enrolling and staying in school.

“ If the children stayed on the streets it would be a problem for both countries, for Lebanon and for Syria. Having children lost on the streets, ending up without a future, illiterate, we know what fate holds for an illiterate society,” Hneineh said.

For the 2015-2016 school year, a joint nation-wide Back to School campaign was launched resulting in the enrollment of 155,000 refugee students in public schools. Many school-aged refugee children are still expected to be out of school. UNHCR has focused on identifying out of school children, especially those with specific learning needs and returning them to formal education including through accelerated learning programs.

70 per cent of the Syrian refugees in Lebanon live beneath the poverty line. Due to the socio-economic situation for their parents, staying in school is not easy as many are forced to leave and help provide income for the family. To prevent drop-outs, education officials say there is a need to continue to invest in support for Syrian refugee students struggling with the Lebanese curriculum and in a qualitative and safe learning environment.

Thanks to the open door policy of MEHE and Norway’s generous funding, tens of thousands of refugee children have been able to access formal education so far.

“Lebanon’s Ministry of Education was very careful to ensure that all Syrian refugee children coming from conflict will not remain on the streets.”

This content produced by Nadine Alfa. It has been edited by Katrine Steingrimsen, UNHCR Northern Europe. *Names in this story have been changed to protect identities.