For many refugees education remains out of reach. School aged children are supposed to get 200 days of school a year.

3.5 million school-age refugees* had 0 days of school in 2016.

*Under UNHCR’s mandate

For many refugees education remains out of reach. School aged children are supposed to get 200 days of school a year.

3.5 million school-age refugees* had 0 days of school in 2016.

*Under UNHCR’s mandate

Education data on refugee enrolments and population numbers is drawn from UNHCR’s population database, reporting tools and education surveys and refers to 2016. The report also references global enrolment data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics referring to 2015.

Introduction

BY FILIPPO GRANDI, UN HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES

The world’s growing refugee crisis is not only about numbers. It is also about time. The fact that there are now 17.2 million refugees under UNHCR’s mandate – half of them under the age of 18 – is dismaying.

Perhaps less immediately shocking, but hardly less distressing, is the statistic telling us that 11.6 million refugees were living in protracted displacement[1] at the end of 2016; of this number, 4.1 million had been in exile for 20 years or more. For millions of young people, these are the years they should be spending in school, learning not just how to read, write and count but also how to inquire, assess, debate and calculate, how to look after themselves and others, how to stand on their own two feet. Yet these millions are being robbed of precious time.

The case for education is clear. Education gives refugee children, adolescents and youth a place of safety amid the tumult of displacement. It amounts to an investment in the future, creating and nurturing the scientists, philosophers, architects, poets, teachers, health-care workers and public servants who will rebuild and revitalize their countries once peace is established and they are able to return. The education of these young refugees is crucial to the peaceful and sustainable development of the places that have welcomed them, and to the future prosperity of their own countries.

Yet as this report reveals, compared to other children and youth around the world, the gap in opportunity for the 6.4 million school-age refugees under UNHCR’s mandate is growing ever wider.

[1] UNHCR defines ‘protracted refugee situations’ as those where at least 25,000 people have been forcibly displaced for more than five years.

As refugee children grow up, their opportunities recede

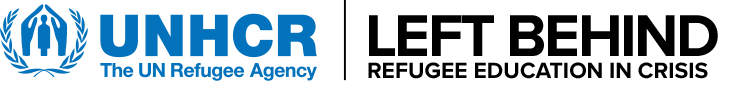

Globally, 91 per cent of children attend primary school. For refugees, the figure is far lower, at only 61 per cent – and in low-income countries it falls short of 50 per cent. Even so, there is progress to report. The proportion of refugees in primary school in 2016 was up sharply on the previous year (from 50 per cent), thanks largely to measures taken by Syria’s neighbours to enrol more refugee children in school and other educational programmes, as well as increased refugee enrolment in European countries that are better able to expand capacity.

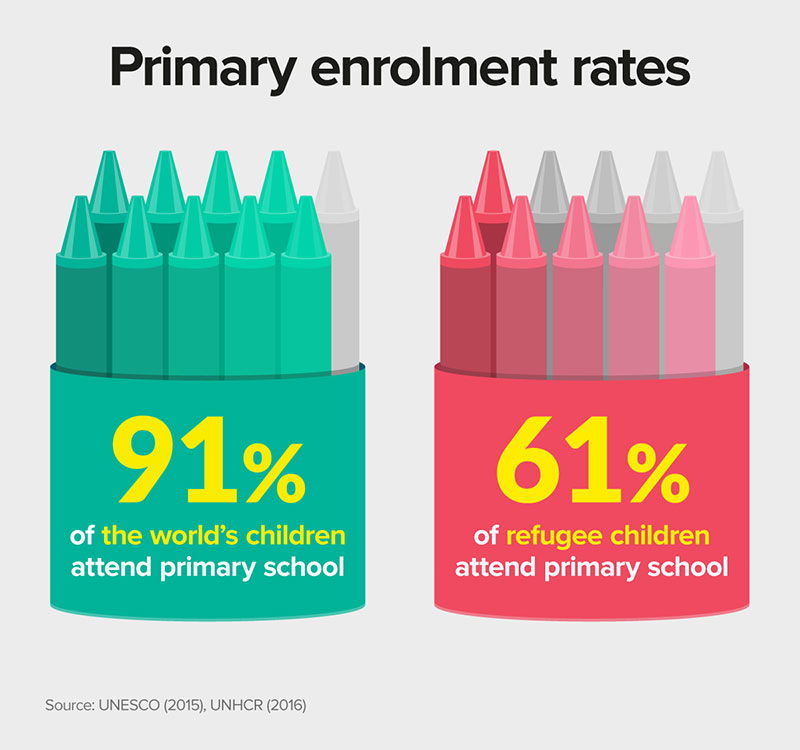

As refugee children get older, however, the obstacles only increase: just 23 per cent of refugee adolescents are enrolled in secondary school, compared to 84 per cent globally. In low-income countries, which host 28 per cent of the world’s refugees, the number in secondary education is disturbingly low, at a mere 9 per cent.

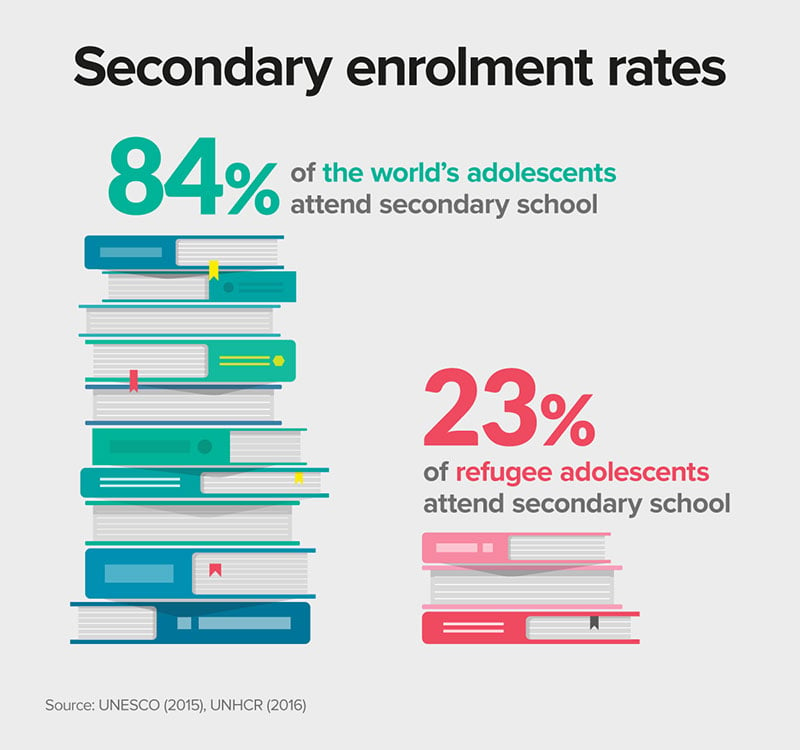

As for tertiary education – the crucible in which tomorrow’s leaders are forged – the picture is just as grim. Across the world, enrolment in tertiary education stands at 36 per cent, up 2 percentage points from the previous year. For refugees, despite big improvements in overall numbers thanks to investment in scholarships and other programmes, the percentage remains stuck at 1 per cent.

A year ago, politicians, diplomats, officials and activists from around the world gathered to forge a path for addressing the plight of the world’s refugees. The result was the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, signed by 193 countries, which emphasized education as a critical element of the international response. Furthermore, the ambition of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) – one of the 17 global goals aimed at ending poverty, protecting the planet and promoting prosperity for all – is to deliver “inclusive and quality education for all and to promote lifelong learning”.

- We declare that education must be an integral part of the emergency response to a refugee crisis. It can provide a protective and stable environment for a young person when all around them seems to have descended into chaos. It imparts life-saving skills, promotes resilience and self-reliance, and helps to meet the psychological and social needs of children affected by conflict. Education is not a luxury – it is a basic need.

- At the same time, education is a social service that requires long-term planning and investment. A child’s schooling must not be curtailed the instant a new emergency arises elsewhere and the emergency response moves on. UNHCR calls for sustained, predictable investment and a holistic approach to supporting education systems in refugee hosting countries. This needs to benefit both refugees and their host communities – most of which are located in low- and middle-income countries that may struggle with inadequate infrastructure and a shortage of capacity.

- In order to square this circle of emergency response and long-term need, we must ensure that refugee children and youth are included in national education systems. Refugees, like all young people around the world, deserve an education of value – to follow a curriculum that is accredited, and to take exams that lead to the next phase of their schooling. UNHCR has learned from decades in the field that parallel systems are poor substitutes – indeed, they are counter-productive, resulting in unaccredited learning that stops children from progressing. Some countries have embraced this principle of refugee inclusion despite their limited resources; others have yet to do so, perhaps because they need more support. This is a shared endeavour with shared responsibility.

- Finally, we must not forget those who take the lead in often overcrowded, under-resourced classrooms. Perhaps you had a teacher who really made a difference to your school days, even your life. Perhaps they opened your eyes to something for the first time, or said a word of encouragement at the right moment, or uttered some harsh truths when they were most needed. The teachers featured in this report walk into the toughest classrooms in the world day after day to help refugees build their own futures. Teachers deserve our wholehearted support – suitable pay, the right materials in sufficient quantities and expert assistance.

If you watch, read and listen to the personal stories in this report, you will be left in no doubt of refugees’ desire to learn and thus to determine their own futures. You will also see how the obstacles to an education pile up as a child grows older and tries to retain a place in the classroom. The gap between refugees and their non-refugee peers is vast, and it is growing.

The education of refugees is a shared responsibility. Committing ourselves to its investment and support will reap plentiful rewards. Last year, with the New York Declaration, no fewer than 193 countries made a promise to the world’s refugees. Now is the time to live up to those promises.