The Stories We Tell Ourselves

By Leah Zaidi

Leah Zaidi is an award-winning futurist and worldbuilding expert who works with companies and countries to design their future. She is a Research Director at the Institute for the Future in Palo Alto, and the Founder of Multiverse Design, an art and design practice in Toronto. She specializes in strategic foresight, systems thinking, and science fiction. Leah is also an Associate Editor of the World Futures Review and is an International Advisor to Sitra Fund, the Finnish parliament’s endowment for the future.

The stories we tell about refugees and the challenges they face are complicated. They are stories of great challenges, of loss, and of overcoming dystopic circumstances in search of a new home. The world of the refugee can be a harsh one. At times, it is a violent, destructive, and unwelcoming world.

What if we could change the story, the stories told of them, and reimagine the worlds that hold those stories? Stories can be rewritten and retold in new ways. Stories can be broken down and remade. And what is the future but a story we tell?

This report will explore existing and emerging narratives in order to identify untapped possibilities for UNHCR, underexplored questions, and grounds for further work. It will use strategic foresight methodology including signal mapping, causal layered analysis, and scenario archetypes to surface new stories and worlds to address refugee crises.

Methodology

The material presented in this report is the culmination of an evidence-driven process that uses strategic foresight methodology. Consider this project “foresight-lite”. A more rigorous, comprehensive project that combines foresight and systemic design may yield further insights and recommendations for UNHCR.

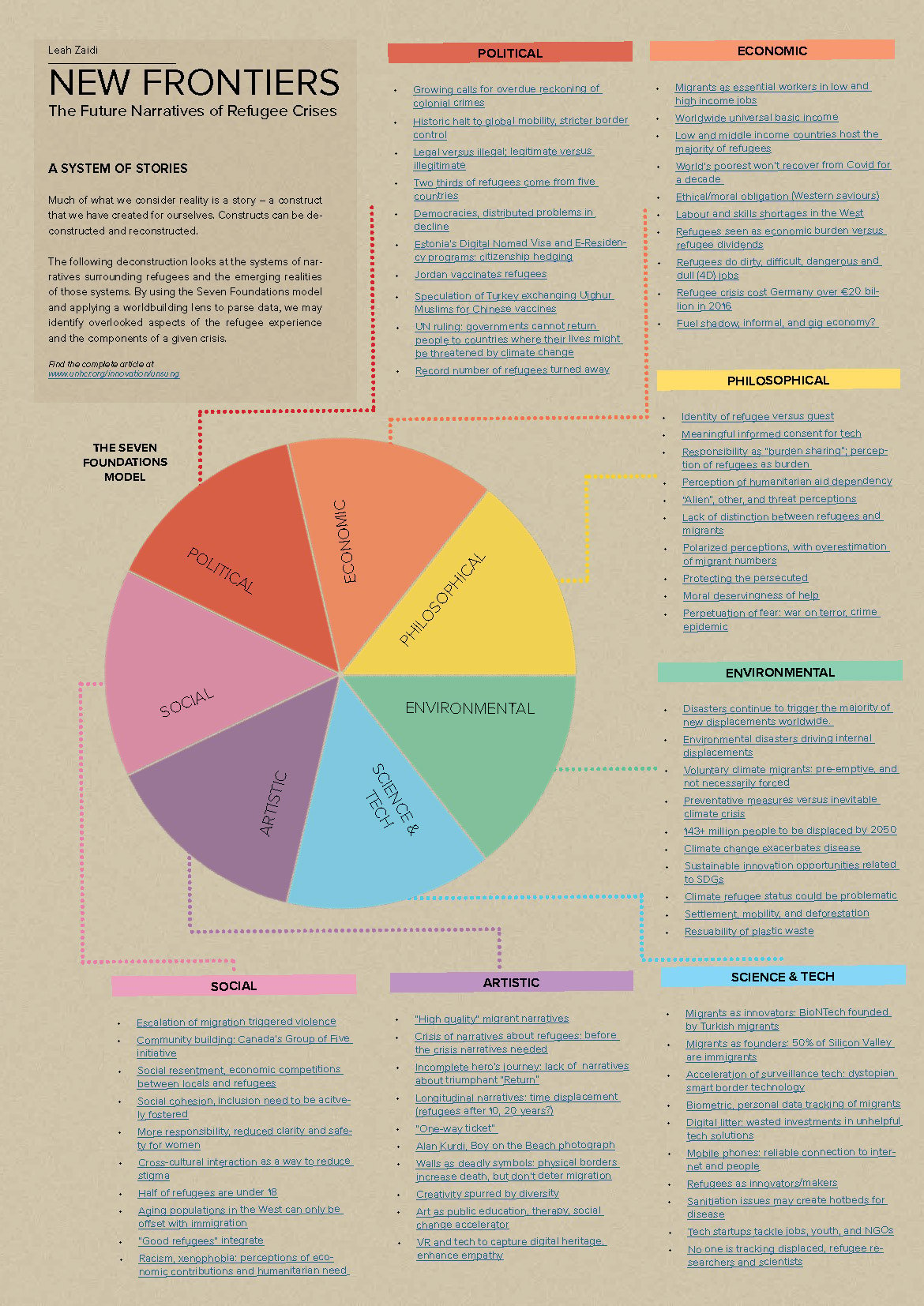

A System of Stories

Much of what we consider reality is a story – a construct that we have created for ourselves. Constructs can be deconstructed and reconstructed.

The following deconstruction looks at the systems of narratives surrounding refugees and the emerging realities of those systems. By using the Seven Foundations model and applying a worldbuilding lens to parse data, we may identify overlooked aspects of the refugee experience and the components of a given crisis.

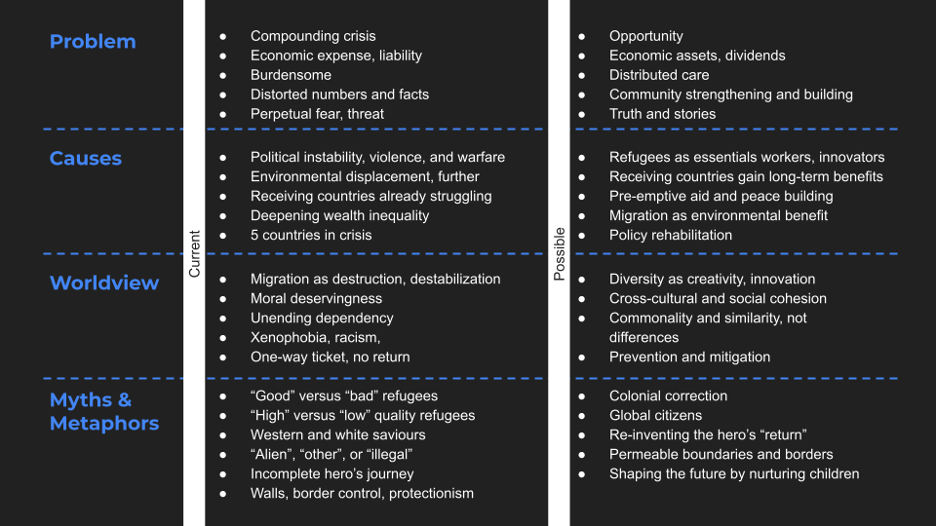

Causal Layered Analysis

The root causes related to displacement are complex, the narratives related to which are deeply polarised. A number of negative myths and metaphors are associated with refugees and their long-term impacts on receiving countries. However, there are positives for countries that receive refugees that often go unexplored. This includes thinking beyond the economic value refugees may add to their host country.

The following Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) explores the current and possible narratives associated with a refugee crisis to surface new insights. It filters the signals and stories identified in the narrative deconstruction. By changing the story, perhaps we can alter perceptions and, therefore, reality.

Based on the CLA, some possible opportunities for rewriting and reimagining current narratives are as follows:

- Signal spotting: how might we identify the signs of a crisis long before it happens?

- Displacement as a social and environmental positive: how might we create safer, sustainable journeys?

- Pre-emptive intervention: how might we prevent a crisis by repositioning future refugees as present-day citizens?

- Universal basic income: how might we establish a truly global income?

- Diversity dividends: how might we emphasise the need for diversity to harness creativity and innovation?

- Distributed care: how might we leverage new technologies to better share responsibilities towards communities?

- Models of peace: how might we preserve democracy without war?

- Colonial correction: how might we redirect international resources to address entrenched inequalities through mechanisms such as climate reparations?

- Nurturing children: how might we pursue intergenerational justice and protect children’s rights in the future?

- Return-less journey: how might we facilitate a safe voluntary return to a stable home country?

- Renew language: how might we clarify language related to forcibly displaced people to better communicate with the public?

- Time travel: How might we better leverage time as a design medium to prevent and mitigate crises?

2040 Scenarios

What does the future hold? While it is difficult to predict how a complex challenge might unfold, we can explore the possibilities.

Insights from the narrative deconstruction and CLA were used to create a set of scenarios. These scenarios are not predictions of the future or descriptions of what might happen. They are evidence-based constructs we use to think about what else is possible and how we might change our approach in the present. Each sentence is embedded with signals, including emerging social issues and political realities. If signals are notes, then scenarios are songs.

Because the scenarios describe the world at large, they may be used by UNHCR and its partner organizations in other projects to provoke new thinking, challenge assumptions, and seek out new possibilities. Think of the scenarios as a playground to imagine different stories and innovations within.

Continuation: Growing Gaps

A continuation scenario explores the “business as usual” future, one in which economic growth persists.

Equality remains elusive. The rich get richer and the poor get poorer, and the world is more divided than ever. Humanity teeters on the edge of crisis, pulled back by feats of innovation that save us from social and environmental collapse. Countries conserve diminishing resources with less capacity for aid and foreign investment. We are caught in a vicious cycle of solving for symptoms. The more crises we encounter, the less money there is to help everyone else.

As the world becomes an increasingly unreliable place, digital worlds become the default. Reality can’t compare to the pristine worlds that many escape into. The more money individuals have, the better the experiences they can afford. Corporations take charge of the Metaverse[1] and NGOs become increasingly reliant on private wealth to support their efforts. Some begin to provide income, sponsorship, and dividends in exchange for digital labour, creativity, and intellectual property.

Algorithms sort and label us according to our potential. Individuals are ranked and evaluated according to their Gross Domestic Potential, and not everyone has equal economic and social value in the present or the future. There are no more universal rights; only return on investments. Big tech puts undisclosed price tags on people. These algorithms are built by a few for the many, and not everyone agrees with their use or the balance of the formula. Some countries and companies create their own, while others aim for conformity and standardization, stifling diversity for the sake of universality.

The data collected creates a tiered system for refugees. Richer nations provide aid to poorer ones, as an efficient method to keep “low potentials” within their borders. Who gets to move and to where is determined by the Good Refugee algorithm, along with the level of care and support they qualify for. Some families are torn apart as high potential children are sent to a different host country from their parents. Others remain together because they are worth more together than on their own. Those who make missteps in the journey, deviations from the perfect path, are doomed to be data-driven off it.

Questions and Considerations

- How do we design systems that prevent the conditions for crises?

- How might humanitarian organizations better recognise and mitigate crisis before it occurs?

- How do we better balance private, social, and sovereign wealth?

- Does the informal economy supersede the formal one?

- How do we prevent privacy from becoming a commodity for the few?

- How do we prevent the creation and use of unethical algorithms?

- What are the consequences of deterministic algorithms for the public sector, international organizations, and local and international NGOs?

- How might biased and unethical algorithms undermine human rights?

Potential Strategies for UNHCR

- Form ethical relationships with corporations and governments to encourage slow, sustainable, and ethical innovation

- Develop principles for ethical, inclusive innovation alongside displaced communities

- Protect human dignity as economic exploitation escalates

- Diversify and protect UNHCR’s income sources

- Advocate and lobby for ethical algorithms

- Develop preventative aid and crisis mitigation programmes

- Develop and advocate for international and national metrics beyond GDP

- Advocate and communicate the UN’s role in cultural technology

- Design multigenerational solutions that keep families together

- Increase resources for local, and community-led efforts

Discipline: Pervasive Walls

A discipline scenario explores bottom-up and/or top-down order and control.

Everything is rationed. Growing demands become harder to meet after a roaring 20s and a slow response to environmental degradation. Food, water, energy, and other basic necessities are in low supply. We learn to curb our needs and our vices, while living on less. Everything is calculated for us from the portions of our food to miles we can travel to the time we’re allowed online – all enforced by the algorithms that run our lives. Grids are carefully controlled. Even families are incentivised to have fewer children, with ample rewards offered to those who self-sterilise.

Pervasive surveillance technology tracks every aspect of our lives. What we do, where we go, and who we meet with. Smart walls and smart borders decide who gets in and who gets out of every conceivable space, including homes, companies, and countries. Smart drones and autonomous vehicles run interference on anyone who tries to break the rules. There is no mobility without permission and payment, both of which are unaffordable for most. Our paths and journeys are laid out before us, deviations from which can become a costly mistake and diminishes our rations. Hacking and manipulating rations become a way of life for some.

Our virtual worlds have borders too as corporations become digital governments. Staying plugged in and connected is a luxury, especially on energy rations. The lack of access paves the way for new inequality tensions as the splinternet creates digital tribes and ever-shifting identities. For many, digital escape is the new drug and, sometimes, the only relief. For some, going off-grid is the new dream. Some refugees find solace in the digital worlds, giving up their real-world allegiances, exchanging privacy for protection. Others find themselves facing physical and digital walls, unable to navigate systems of control designed to keep them out.

War moves to cyberspace too, with most conflict and damage carried out online. Civilians are not off limits. Digital infrastructure and grids are insecure, and cybersecurity is a national priority for all countries. Peacekeeping and cooperation fall to the wayside as digital defence requires more attention and resources. Controlling information is key, as each entity fights to establish its version of the truth.

As war and conflict go digital, the real world is left to recover. Real-world violence tempers. The environment recovers though it does not return to its original state, with many species lost in the roaring years. All that restraint has trade-offs.

Questions and Considerations

- How might we ensure that digital worlds are safe, equitable, and inclusive?

- How do we protect marginalised communities in cyberwar?

- What forms of discipline can we enact in the present to curb the need for high discipline later?

- How might digital worlds change the concept of “field” work i.e. digitally displaced individuals?

- How might we respond to organizations that follow online and offline jurisdictions rather than national borders?

- How do we protect vulnerable populations from misinformation and disinformation campaigns?

- How might we protect identity and culture in the emerging digital world?

Potential Strategies for UNHCR

- Advocate for a body of the United Nations that addresses cyberwar and digital worlds

- Establish and communicate principles for digital borders and equality within the Metaverse (i.e. the summation of all virtual spaces and related constructs)

- Advocate for diversity and inclusion in the creation of digital worlds

- Advocate for data protection of vulnerable populations

- Advocate for universal digital human rights

- Develop safe and ethical guidelines for smart walls and borders

- Provide access to leisure for welfare and wellbeing

- Advocate for equal and secure access to energy, data, and the internet

- Consider the role of the UNHCR in de-digitalization and reality rehabilitation

Collapse: Dying Lands

A collapse scenario explores a systemic breakdown.

The Earth is dying. Erratic and extreme weather are the norm, ocean levels rise and swallow islands whole while eating away at our shores, and keystone species die-off at alarming rates. Biodiversity collapse seems all but imminent as our ecological systems hit their tipping points faster than we had anticipated.

Nations rush to secure precious little water and food supplies by any means necessary, even if those means are violent. Resources dwindle. Disease flourishes. Trust and diplomacy break down as each country fends for itself. Wealthier nations use their resources to protect their citizens and fortify their armies, grappling with fallouts of mass internal displacement. Poverty, fear, and ongoing destruction become the great equalisers. We stay in small numbers to protect ourselves and what little resources we have left. The outside world is unsafe, and all we have left are our containers and our digital escapes.

As the Earth suffers, we suffer with it. Genocide becomes an everyday reality as more displaced people find themselves without a home. Our lands, and the worlds we once knew, are no longer habitable. Trauma is inherited from parent to child, compounding generational injustices. As millions begin to move within and between countries, democracy is destabilised. Fanatics and eco-fascists rise to power, promising safety from the “others”, claiming refugees will damage the social and environmental fabric or society. Authoritarian nations use the crisis to rid themselves of undesirable populations, blaming expulations and mass deaths on environmental disasters. Some trade people like cattle, exchanging hard labour for aid and supplies. Borders become battlegrounds, keeping some locked in and others locked out. Few live through to reach the other side, only to find new wastelands waiting for them. Pre-emptive drone strikes are carried out against refugees to keep them from reaching their destinations, in the name of security. There is nowhere safe to run to.

Questions and Considerations

- How might we better communicate that climate change exacerbates existing and entrenched inequalities?

- How do we ensure we are not enabling the wrong future or defuturing other alternatives?

- How might we diversify the income streams of international aid organizations?

- How might we rethink long-term, unallocated funding?

- How might we better foster relationships between refugees and their host communities?

- How do we ensure the cost of aid does not escalate as climate change worsens?

- How might we enable agile, place-based and local response to crises?

- How might nature “seek refuge”?

Potential Strategies for UNHCR

- Advocate and work towards environmental flourishing to prevent future crises

- Communicate with and support countries to prepare for climate-driven internal displacement

- Engage in environmental protection to prevent future refugee crises

- Analyse and establish sustainable practices throughout UNHCR e.g. minimising employee flights

- Seek out and fund innovative Earth-centred and regenerative aid efforts

- Identify and improve opportunities for remote help

- Invest in and develop robust environmental degradation simulations

- Design mitigation and response strategies to the collapse of global food supply chains

- Identify and invest in land reclamation efforts that restore shorelines

- Anticipate future protocols and agreements that minimise eco-injustices

- Establish and iterate a global climate crisis plan

Transformation: Open Worlds

A transformation explores a high-tech and/or high-spirit scenario.

“Planet and people first” is the new paradigm. Climate positive solutions become the economic and political standards of our world. Biophilic design, biomimicry, cleantech, and renewables are dominant technologies as we increasingly become a life-centric species that aims to maximise environmental and social health. Stewardship, connection, renewal and purpose are the values we cherish most. Once disparate aid organizations come together under a single banner and unified cause, providing holistic care and healing cycles of generational trauma.

A global Corporate Social Wealth tax is introduced as an investment in a brighter future, along with an Environmental Overuse tax to ensure no one operates outside the planet’s carrying capacity. We recognise that no person or entity is disconnected from the tree of life. What nourishes the tree, nourishes the branches and the leaves. The elimination of tax havens opens up new opportunities for wealth sharing. Health is a fundamental right that is redefined to include basic universal needs such as food, water, and housing. The active dismantling of people and planet-fearing organizations provides the funding needed for reparations.

The United Nations Stewardship Organization (UNSO) works towards creating a flourishing society by enacting models of peace. Employing artificial intelligence, digital twins, and climate simulations improve, we learn to spot the seeds of a crisis before it happens. Anticipation and early crisis intervention through data and design prove far more effective and less costly than the alternative, paying future social dividends on present monetary investments. With all those advancements, the online world paves the way for a Protoverse – a place where experimental science, policies, cultural realities, and more are imagined and simulated before they are brought into the real world to transform it. The Protoverse is built by all for all; a decentralised, plural world in which no one has more power or resources than anyone else.

People still migrate but not because we are in crisis. We migrate to exchange culture, knowledge, and wisdom, as ambassadors and keepers of community and cohesion. We recognise we are keystone species that can shape the world for the better. Migration paths are soulful, voluntary journeys – an honourable role that helps rewild the world and provide planetary care, undertaken with assistance and robotic aid. Our living world is our art.

Questions and Considerations

- How do we move beyond crisis to flourishing?

- How might we ensure digital worlds are built for the many by the many?

- Should we enshrine environmental rights as human rights?

- What environmentally friendly forms of conflict are we overlooking?

- How might we enable joyful migration?

- Who might be lost or underserved by transformation and/or transitions?

- What values should be deemed “keystone” values (foundational, life-centric values)?

- How do we unify disparate aid organisations under a single goal to eliminate the need for aid?

- How might we encourage and fund stewardship technology?

Potential Strategies for UNHCR

- Develop crisis anticipation and intervention models including criteria for pre-emptive action

- Invest in understanding how indigenous knowledge can contribute to ethical innovation and place-based design efforts

- Advocate for increased funding and venture capital for robust environmental simulations and models i.e. constructing a digital twin of the Earth and its critical ecosystems that update in real-time

- Improve the journey of migrants to make them safer and sustainable

- Improve communication and coordination between different organizations that assist refugees

- Unified stewardship, and common resources

- Redefine the concept of home and relationship with land

- Provide “soul” aid: what are the conditions for long-term wellbeing?

- Educate the private sector on slow, planet-centred and ethical innovation

- Advocate for climate positive policies and innovations

Narrative Strategies

As we look to the future, UNHCR may journey into new frontiers that present both challenges and opportunities related to its mandate. The following recommendations are derived from the research and scenarios presented in this document and highlight areas that require further exploration.

Human Rights in the Metaverse

The metaverse (our shared virtual worlds) is quickly emerging with all the inequalities present in the physical world. Digital human rights, digital borders, access, biased algorithms, exploitation of vulnerable populations, data privacy, etc. are all factors that UNHCR may need to address with more comprehensive efforts in the near future. It is important for the organization to take a proactive stance on shaping this emerging reality rather than reacting to its inequalities as they surface. We need a declaration of human digital rights and operating principles for an inclusive, open Metaverse.

This may include:

- A UN. charter of digital rights and freedoms, with specific sections pertaining to the rights of children

- An exploration of protocols on virtual land ownership, privatized virtual spaces, and digital borders

- A treaty advocating for fractional ownership of the Metaverse

- Designing parameters for a decolonised Metaverse

Additionally, stories about the Metaverse are dominated by cyberpunk narratives (which often explore themes of inequality and oppression). While these narratives serve as important warnings about the future, they are one side of the equation. We need positive stories of equality, inclusion, and flourishing in an open, thriving, and diverse world. These stories should include depictions of positive and altruistic behaviour in order to set an example of peace in virtual places.

Business Models of Peace

There are clear and easy to articulate business models and supply chains for war. It is much more difficult to identify the business models and supply chains for peace. The economics of peace must be mapped and communicated, with clear step-by-step guidelines for how to enact peace and engage in what can be called “peace-profiteering”. The collection and dissemination of stories that exemplify peace-profiteering may set a positive example of how to balance collective good and economic wealth.

Business models of peace may further benefit from a reimagining of economic models. Concepts such as degrowth, regeneration, and Kate Raworth’s doughnut economics might serve as seeds for new narratives.

Rebuilding After the Crisis

Many dystopias end after a battle is fought and the hero wins. What we often do not see is the long and difficult process that comes after. We lack mainstream narratives that demonstrate how we rebuild and recover in the aftermath of a crisis, i.e. stories that show the challenges that come with transformation and change. It may benefit UNHCR to imagine stories of how nations and people recover, including the challenges they might encounter navigating peace and sustainability, how those challenges are overcome, and the actions and behaviors that are required to achieve success. In particular, it might be worthwhile to write and explore stories of how climate ravaged areas restore ecosystems and how war-torn nations heal and reconcile.

This could include sharing existing stories of how nations have recovered from past crises to inspire change and healing.

Safe, Sustainable Journeys

Refugees make perilous journeys under immense emotional, psychological, and physical pain. While the ideal future is one in which there is no need to make such a journey, the present-day circumstances call for ensuring safer journeys. Designing and exploring refugee journeys of the future may help uncover novel ideas to improve current journeys.

Unlike other species, human migration can often have a negative impact on the environment. While it is the wealthy who are disproportionately responsible for climate change, ensuring that all migrations and journeys are sustainable is a worthwhile pursuit given the implications of environmental degradation. [2] [3] UNHCR should consider supporting innovations that enable sustainable journeys and climate positive movement. Partnerships with organizations that explore renewables, biophilic design, biomimicry, and biodegradables may be worth exploring. For instance, how might we map future migration paths and transform them for future needs (e.g. planting seeds for future food sources)?

It might be helpful for UNHCR to develop a comprehensive systems map of existing sustainable technology and solutions that could be beneficial in current and future crises. Doing so might surface new uses for existing solutions while identifying gaps in innovation. Such an artefact might provide value to partner organizations and prospective innovators. For instance, how might other nations benefit from Japan’s use of waste to aid land reclamation efforts? [4]

Exploring speculative stories of safe, sustainable journeys might yield new insights and ideas for real-world journeys. It might also help to capture migrations of other species as narratives to better understand how humanity might serve as a climate positive keystone species. The system is missing Solarpunk narratives: stories that subvert the systems that prevent brighter futures from emerging. These stories feature sustainability, renewables, and environmental flourishing. Solarpunk has yet to become a mainstream genre of science fiction and may lend itself well to stories of refugees seeking brighter futures.

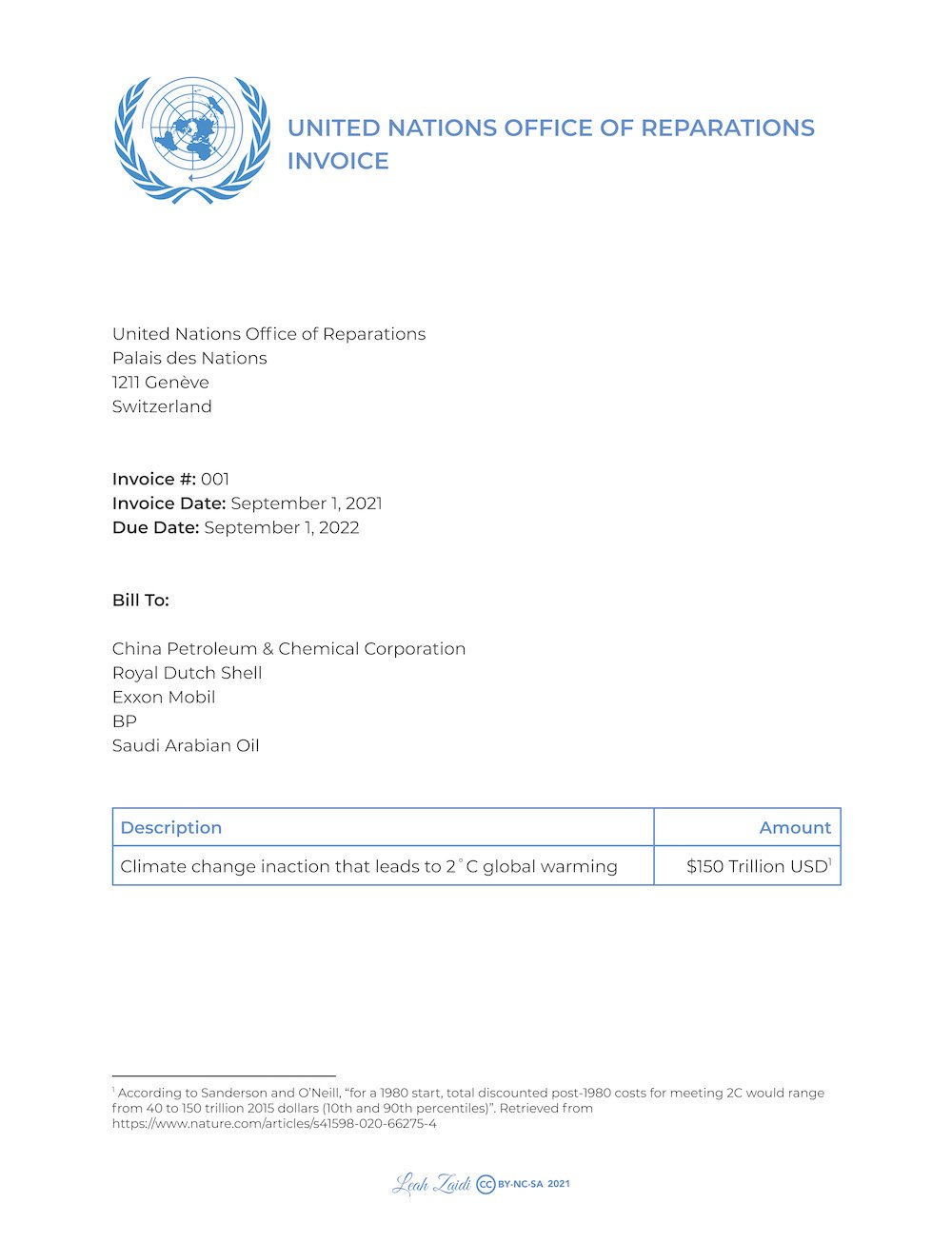

Colonial Corrections

Colonisation is a root problem, the cascading events of which have been felt through centuries. Advocating for ways of decolonising the aid sector and redirecting resources through reparations (such as climate reparations) may help mitigate future crises and curb current challenges. It is important to note that the world’s poorest may bear the brunt of climate change and consequent displacements, though the privileged are disproportionately responsible. Climate change is “a brutal act of injustice”. [5]

Reparations are long overdue with signals for a “colonial reckoning” emerging. How to facilitate reparations while maintaining global economic stability is an important and timely conversation. The role of the private sector and tax havens should be considered. Telling stories about reparations and how it might be facilitated may be beneficial.

The American Refugee Crisis

It is a mistake to think that any part of the world is safe from the consequences of climate change. Wildfires in California are creating the conditions for migration.[6] A record-shattering heatwave in British Columbia, Canada killed 130 people.[7] The Netherlands might disappear altogether.[8]

It is important for residents of wealthier nations to understand they may be displaced someday. If environmental degradation accelerates, there may be nowhere left to seek refuge. Telling evidence-based stories of future refugee crises and displacements may be critical in communicating the consequences of inaction. It may also help diminish harmful narratives of refugees and migrants as “others”.

Time as Design Dimension

Time plays a significant role in a refugee crisis. Generational trauma plays out over decades, if not centuries. Almost half of all refugees are children, who may grow up with different relationships to the country of departure and host country than their parents.

Seeking early, anticipatory intervention opportunities in the present may mitigate the need for greater resources and efforts later. Identifying and documenting the signals of a crisis before it happens, pre-emptive and precautionary funding and aid for at-risk populations, and investments in children are solutions that may help minimise future crises. Communicating the implications and potential solutions as narratives rather than as facts may help create emotional urgency and desire to act.

Our Children

“Refugee” is a loaded word that has long-term implications for anyone who bears it, including children. To foster a sense of collective responsibility and oneness, UNHCR should consider transitioning from the words “refugee children” to “children” in the stories it tells publicly (while ensuring children retain the protections afforded by a refugee status in formal documents). Language is soft power and can alter a system without antagonising the existing power structure. Language is the conduit between thought and action. New language enables new stories. Though it seems like a minor change, using language that suggests collective responsibility may help inspire collective action, particularly as we experience environmental degradation — a challenge all children will inherit tomorrow.

Non-Existence

Charitable and aid organizations have not previously identified a single purpose that drives their strategy and operations, though one exists. The purpose of any given charity and aid organization should be to address its cause so effectively, its existence is no longer required. Systemic reform that eliminates root problems should be the desired outcome.

Rather than addressing a crisis once it has begun, UNHCR should seek opportunities and innovations that alleviate a crisis before it begins.

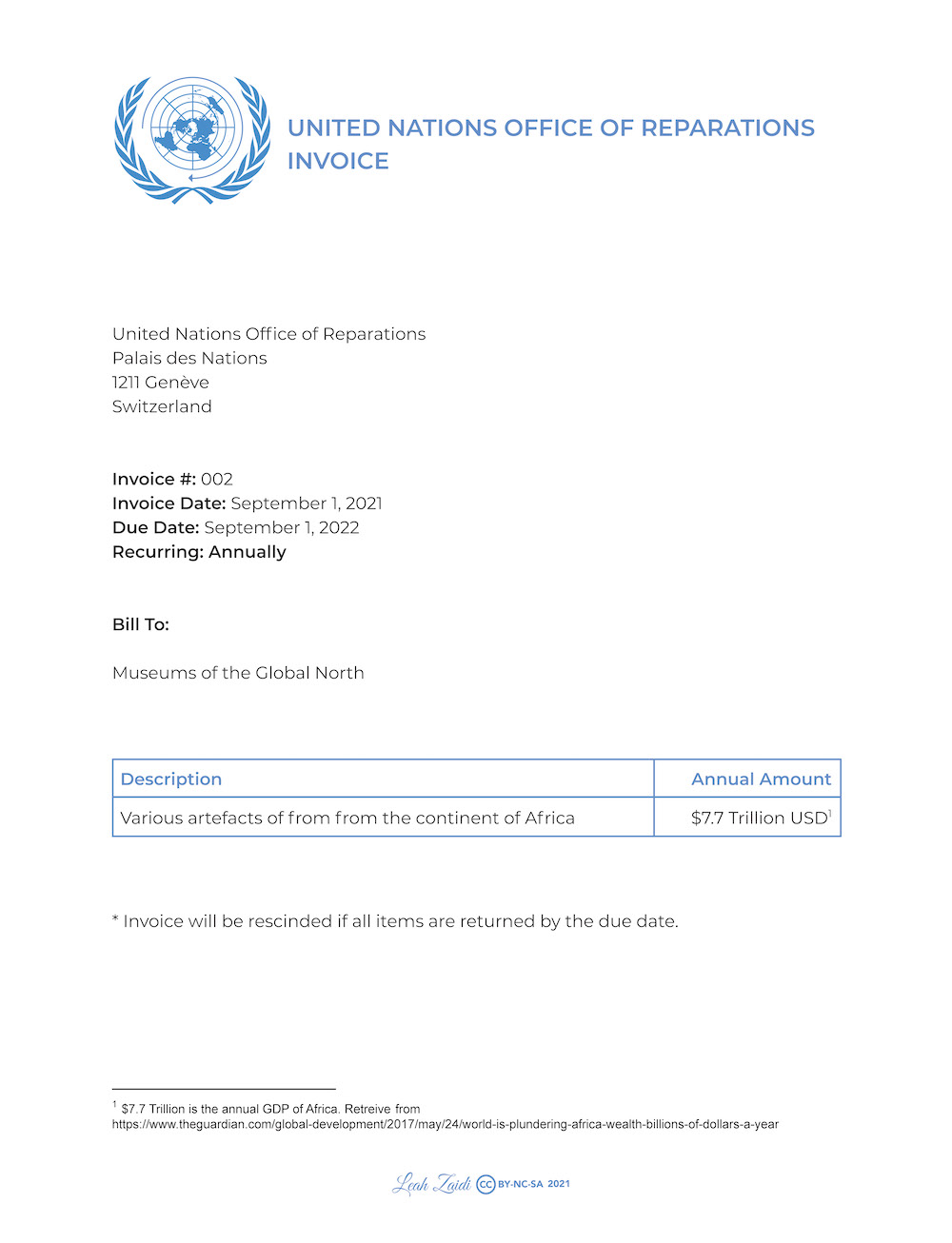

Design Fiction: Reparation Invoices

Creating an artefact from the future can make an abstract future more tangible and visceral. Design fiction allows us to explore and critique the present and future by challenging our assumptions, shifting our perspective, and provoking conversations.

The following artefacts are invoices issued by the fictional “United Nations Office of Reparations”.

The Next Chapter

As we look ahead to the impending challenges the future might bring, it is important to remember that change is possible though it is not always easy or simple. The future is shaped by our present-day actions. The purpose of looking ahead is to determine what we should and must do now — to pull the future into the present and make it our reality.

We stand on the precipice of a new, uncertain world. Together, we can build a better one.

[1] The Metaverse is a portmanteau “beyond” and “universe”. It refers to a collective virtual world that encompasses all virtual spaces and constructs such as virtually enhanced physical reality and the internet.

[2] Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/nov/17/people-cause-global-aviation-emissions-study-covid-19

[3] Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/protection/environment/3b039f3c4/refugees-environment.html

[4] Retrieved from https://www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2017/02/18/environment/wasteland-tokyo-grows-trash/

[5] Retrieved from https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/climate-change-is-connected-to-poverty/?template=next

[6] Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/oct/02/climate-change-migration-us-wildfires

[7] Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-57654133

[8] Retrieved from https://www.politico.eu/article/when-will-the-netherlands-disappear-climate-change/

This page is part of UNHCR’s Project Unsung collection and portfolio. Project Unsung is a speculative storytelling project that brings together creative collaborators from around the world to help reimagine the humanitarian sector. To discover move about the initiative and other contributions in the collection, you can go to the project website here.