By Barbara Adams

Barbara Adams is a sociologist whose interdisciplinary research looks at how knowledge is produced and political action is initiated through art and design projects. Barbara co-edited the book Design as Future-Making and is co-editor in chief of the journal Design and Culture. She is Assistant Professor of Design and Social Justice at Parsons School of Design and was previously a postdoctoral fellow at Wesleyan University.

It is the task of the fabulating function to invent a people.

Gilles Deleuze

The Work of the Imagination

It may seem unremarkable to note that creativity and imagination are essential and active capacities in world- and future-making. Although this seems obvious, we do not ordinarily turn to artists to address our most pressing social, political, and economic issues. Yet, over the past two decades, there has been a reinvigoration of socially engaged practices that have situated artists as agents in social and political fields. These creative practitioners make provocative assumptions about the kinds of knowledge and action art might initiate. They respond to contemporary crises and address large-scale issues such as the persistence of poverty, the marginalisation of social groups, the institutionalisation of inequalities, the commodification of culture, and the ways in which legacies of imperial exploitation continue to shape our world.

By generating situations and creating environments that offer a miniature vision of the sort of society we desire, these art projects embrace an ethos of world- and future-making- that nurtures participation and public discourse. Employing collective and creative practices that draw from artistic traditions based in abstraction and performance (among others), these works go beyond the limitations of representing or elaborating the world as it is—proposing something otherwise.

What if institutions and entities outside the realm of art embraced and exercised these practices? What if the generative quality of creativity that reaches beyond the limits of the individual imagination was adopted as a virtue in solving social and political problems on an organizational scale? What if organizations and institutions focused on the emergent and exploratory capacities of artistic practice versus the neoliberal framing of creativity as innovative and entrepreneurial, as something calculable, result-driven, and clearly defined?

How might we build on the limited but rich history of embedding artists (or their approaches) in agencies and organizations? Mierle Laderman Ukeles, for example, has been an artist in residence at the New York City Sanitation Department since 1976. The artist John Latham called artists embedded in businesses and organizations “incidental persons,” with “incidental” specifically indicating activities based in not knowing and without predetermined intentions. Latham initiated the Artist Placement Group that, during the mid-1970s, placed artists in industrial, governmental, and administrative settings ranging from the fishing industry to mental healthcare settings to environmental agencies. The artists were brought in not to solve problems, but to offer other ways of seeing and framing the work of these organizations, interrupting existing institutional codes and creating opportunities for developing new patterns of action.

Beyond the Gallery

Artists working in an expanded field that operates beyond the museum, the gallery, and object making, play a principal role in the ability of society to inaugurate new forms of itself. Taking people as their central medium, many contemporary artists anticipate changes in presence and create experimental scenarios where participants can rehearse alternate ways of being and acting. They recognise that art provides a forum for communication where people can come together to construct something otherwise—not only diagnosing the world in which we live, but also acting as a dissenting force, offering perspectives and experiences that counter and exceed dominant social and cultural forms.

This type of socially-engaged art practice is propositional, speculative, and deeply tied to the sociological imagination that questions the given nature of society and actively pursues possibilities for change. On its most basic level, the sociological imagination involves a disposition where we seek to understand the individual’s relation to society by connecting personal biographies to larger, collective histories and individual troubles to broader social issues. According to C. Wright Mills, who coined the phrase “the sociological imagination,” the term refers to a general disposition that questions the given nature of society and actively pursues possibilities for change. Artists who engage the sociological imagination cultivate images and scenarios that explore what society might become, mobilising people to recognise their power to collectively revise the terms that govern our lives.

As social sculpture, artworks can engage public audiences and collaboratively propose other ways of living in the world and alternative means for addressing conflicts and power. This requires what anthropologist and globalisation scholar Arjun Appadurai calls “the work of the imagination”—a collective activity of imagining that can act as the impetus for social change, something he sets apart from the escapism of fantasy.

When we frame creativity not as an individual capacity, but rather as “a socially distributed and participatory process,” we underscore the potential of the sociological imagination to manifest change. This builds on Joseph Beuys’ claim that, “Every human being is an artist, a freedom being, called to participate in transforming and reshaping the conditions, thinking and structures that shape and inform our lives.” With this claim, Beuys moved creativity beyond the special realm of the art, not suggesting that everyone create artworks as we typically understand these, but arguing that creativity could manifest in all areas of specialisation from farming to physics to politics to social work.

Making the World

Many artists leverage performative, experiential, and ambiguous scenarios, to develop transformative methods of social engagement. Invested in collaboration, these projects mobilise publics, foster communities, and build solidarity across difference. In creating material objects, such as stories, songs, public spaces, artworks—even policies and scientific experiments, meals and social events—we produce not just the artifacts themselves, but also the undeniable recognition that we share a world in common. In materialising the world, artists, poets, historiographers, monument builders, writers, and other creative practitioners (including all of us, as homo faber) provide a ‘home’ where we can gather to create a world and build a future. The public square, the library, the table, the museum, the garden, the sidewalk, and the neighborhood provide space where people can convene, collaborate, and create the worlds in which they would like to live.

Prototyping, Proposing, and Performing Alternatives

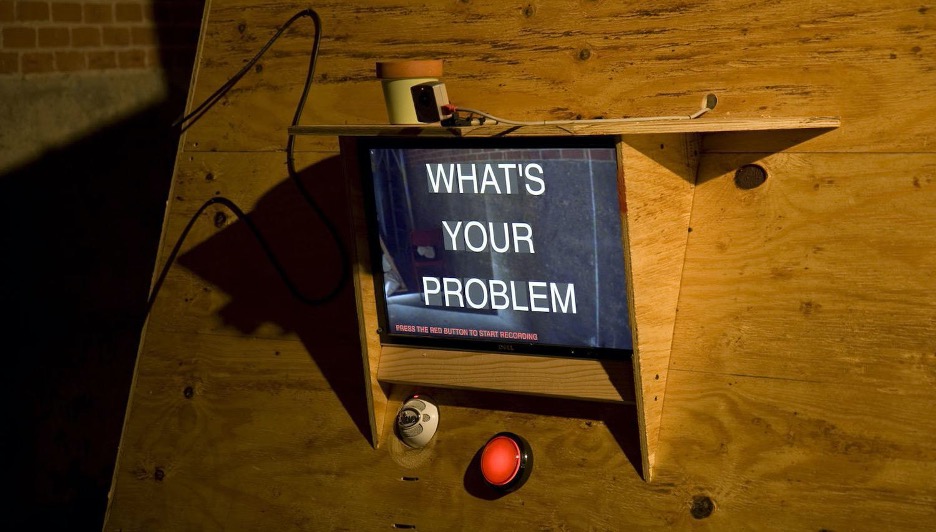

Because social practice-based art is not normally focused on objectives and ends but on experiences and means, these works can accommodate ambiguity, tension, and conflict in ways that other efforts that seek clear resolution or consensus cannot. Artists are given licence and are encouraged to experiment and move beyond the given and known. There is a proliferation of projects in contemporary art that involve participants in scenarios and environments that are ambiguous. This is a particular sort of social practice—where artworks manage to inhabit a double status—where they are both a thing and a proposition of that thing.

Because the artwork is that which it purports to be, while also not that thing, it has the potential to destabilise norms and expectations. Being at a garage sale in the atrium of New York’s Museum of Modern Art is not the same as being at a tag sale in an actual garage. It is also not the same as most works showcased in the museum’s atrium. Likewise, a Spanish language bookstore in a gallery that functions as both an art installation and an actual store, creates a sense of estrangement. As such, there is uncertainty in terms of how to act—“Are these things really for sale?” (yes); “Is this really art?” (also, yes). The ambiguity creates an odd situation where the terms of social interaction and behaviour (even if only on a small scale) need to be explored through experimental means. The feeling that there are many possible ways to perform and interact can be simultaneously uncomfortable, festive, and mysterious. This alienation effect can prompt critical reflection and can produce novel modes of action.

In some cases, these artistic efforts are exemplars of a prefigurative politics where they enact the very thing they (hope to) become. Prefigurative politics underscores the importance of transforming social relations as a precondition for broader structural change. Activist and social scientist Carl Boggs explains prefiguration as the embodiment of “social relations, decision-making, culture, and human experience that are the ultimate goal.” This is typically done by piloting, developing, and propagating counter-institutions and alternative procedures on a small scale, demonstrating through actual participation and social engagement, how things might be done differently.

In other cases, this form of artistic work introduces new variables, clearing space and inviting the not-yet-known and unanticipated. As operational, these works act as engines in making other possibilities sensible. They disrupt and unframe allowing other sorts of social performances to intrude and shake loose ossified practices and relationships, making room for different encounters and ways of behaving. These artworks play with codes, signs, expectations, and norms. They produce a sense of estrangement in proposing an imaginative framework that is similar to, yet differs from, reality. The ambiguity creates an odd situation where the terms of social interaction and behaviour need to be explored and reconsidered.

Without a clear script, people find it necessary to improvise. These projects are a bit like sociological breaching experiments that intentionally violate social rules to understand how people will react and recalibrate. Sociologist and ethnomethodologist Harold Garfinkel made the case that disrupting everyday, expected activities—things like standing ‘backwards’ in an elevator—allows us to see how society maintains social norms and resists social change. The artistic realm affords a measure of liberation to breach norms and experiment. Displacing and decentring ways we would normally act in a given situation invites alternatives and can also solicit participation from people who might normally not be included. Broadening modes of action and widening participation, these artworks propagate the worlds they hope to bring into being.

Contemporary philosopher Jacques Rancière argues that social and political orders are founded on the distribution of the sensible. Some groups of people and their ideas can be sensed while others remain outside sensibility. Who can be seen and who can be heard, ultimately determines who gets to participate in decision-making processes. To see and to hear those normally rendered inaudible and invisible by current systems, we need to invent fictions that demonstrate new alliances and forms of action—ultimately constructing new “communities of sense.” Art can create fictions with a strong experiential dimension, and as Rancière compellingly argues in The Emancipated Spectator:

Aesthetic experience has a political effect to the extent that the loss of destination it presupposes disrupts the way in which bodies fit their functions and destinations. What it produces is not rhetorical persuasion about what must be done. Nor is it the framing of a collective body. It is a multiplication of connections and disconnections that reframe the relation between bodies, the world they live in and the way in which they are ‘equipped’ to adapt to it. It is a multiplicity of folds and gaps in the fabric of common experience that change the cartography of the perceptible, the thinkable and the feasible. As such, it allows for new modes of political construction of common objects and new possibilities of collective enunciation.

In producing counter forms that anticipate different reality principles, artworks can help us visualise something otherwise. This work interrupts the taken-for-granted and by clearing the way for alternatives, provides conditions for people to mobilise and act in ways that surpass the actual and reach into the possible—as evidenced in the two examples discussed below.

Estranging Humanitarian and Development Imaginaries

How might we develop shared imaginaries that extend beyond those generated by the imperial and colonial logics that condition and limit what we envision? Our capacity to imagine, act, and create a world that is different from the one in which we are located, can be nurtured through artistic means.

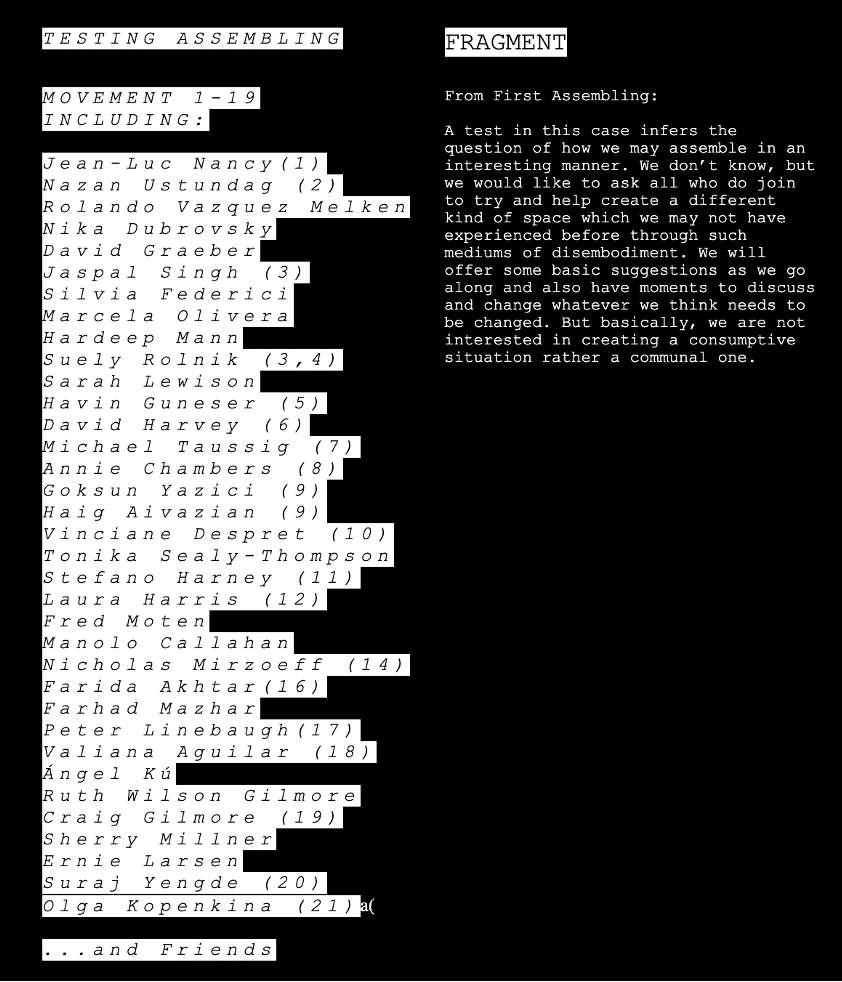

1.0 Unlearning Imperialism: ‘Developing the First World’

When the Ghana Think Tank “develops the first world” by setting up think tanks in the “third world” and asking participants to solve problems posed by those in the so-called “developed world,” they rework the notion of who is needy and who has expertise. This collective group of artists upturn dominant narratives. They reject the way that help has become professionalised and institutionalised, positioning people as “at-risk” and in need of diagnoses and intervention from the Global North. In opposition to discourses of colonialism, the Ghana Think Tank addresses histories of oppression and dispossession by shifting power dynamics through public art projects.

Challenging the notion of who can legitimately engage in inquiry, produce knowledge, and address the problems of others, the Ghana Think Tank collects problems from people and communities in North America and Europe and sends these to think tanks they set up in “developing” countries. Their work has been guided by think tanks in Ghana, El Salvador, and Iran, by Sudanese refugees seeking asylum in Israel and a group of incarcerated girls in Boston, among others. In challenging who is needy, they echo the findings of anthropologist Liisa Malkki. In her book, The Need to Help, Malkki draws from her ethnographic research with highly trained and experienced, international aid workers from the Finnish Red Cross. Shifting attention from the recipients of aid to humanitarian aid providers, Malkki’s inquiry found “an unmistakable neediness” on the part of humanitarians. These service providers expressed a strong desire to escape the mundane world of home for “the world outside”—a palpable neediness that giving and helping alleviated.

In “developing the first world,” the work of the Ghana Think Tank plays with the complex notion of need. They hold up a mirror to the paternalism of the Global North and its perceived role in providing expertise and aid. In collecting problems from communities in places such as the predominately white, upper-class town of Westport, Connecticut in the US. Residents of Westport shared concerns about a lack of diversity in their community, while researchers at the think tank in El Salvador found that Westport is actually quite diverse. In reality, the predominantly white, upper-class residents had little engagement with the diversity of the community, ignoring, in particular, the extensive wealth of experience and diversity found in the people performing critical domestic labour in their neighbourhoods. Using this as their starting point, the think tank suggested Westport residents hire local day labourers, paying them their regular rate to attend social functions.

In response, workers were invited to parties to socialise, snack, and drink wine alongside Westport residents who were provided the opportunity to practice their Spanish. In following the recommendations of the think tanks, this performative artwork effectively manifests other possibilities and—to return to the passage above—“disrupts the ways in which bodies fit their functions,” multiplying connections and disconnections, reframing the fabric of common experience.

2.0 Exile as a Political Practice

For their art project, Refugee Heritage, DAAR (Decolonising Architecture Art Residency) prepared and submitted an application to UNESCO nominating Dheisheh Refugee Camp in Palestine as a World Heritage Site. The project, “an attempt to imagine and practice refugeeness beyond humanitarianism,” destabilises the status of both sites of exile and of heritage. It actively debates our understandings of sovereignty, culture, and aesthetics by acting “as if.” The application is both speculative and real, both a provocation and an actual application. In reframing the status of the camp, the project, “demands redefining the subject of the refugee itself as a being in exile and understanding exile as a political practice of the present capable of challenging the status quo.” It challenges us to, as Sandi Hilal from DAAR says, value refugees beyond misery. The application includes a dossier from architectural photographer Luca Capuano, whom UNESCO had commissioned to document forty-four sites in Italy inscribed on the World Heritage list. He was asked to document Dheisheh Refugee Camp with the same care, respect, and search for monumentality he uses when photographing historical sites in places like Venice or Rome.

DAAR frames the refugee camp as a place with a rich history, a wealth of stories, and an abundance of knowledge. Like the Ghana Think Tank, DAAR understands the ways in which knowledges, in the plural, are always located and partial—what Donna Haraway calls “situated knowledges.” For over two years the implications for Dheisheh’s UNESCO nomination were discussed with organizations, politicians, conservation experts, activists, governmental and non-governmental representatives, and proximate residents.

In their project statement, DAAR notes that “the end goal of the project is not UNESCO’s approval, but to start a needed conversation about the permanent temporariness of camps, and the connection between rights and space.” By going through the process of nomination, participants point to an embodied shift and how this made future possibilities visible: “In filling out the form, we saw ourselves as new inhabitants entering an old architecture, transforming it to adapt to a different form of life.” This demonstrates an emergent form of “collective enunciation,” producing a fiction that monumentalises the people yet to come. In doing so, this project moves beyond the limited frameworks of humanitarian narratives, provocatively producing other possibilities for organising and mobilising, changing the cartography of the perceptible.

Fabulating Futures, Naming New Narratives

Through deconstructing and reconstructing the dominant narrative, these artworks explore how we might imagine more expansive alternatives and possibilities, broadening and reframing the methods we use for speculation. As “critical fabulation,” a method elaborated by writer and African American scholar Saidiya Hartman, these projects “illuminate the contested character of history, narrative, event, and fact, to topple the hierarchy of discourse, and to engulf authorised speech in the clash of voices.” Fabulation, broadly understood, involves the collaborative process of inventing the people yet to come through myth making and monumentalising the ‘not-yet.’ Art plays a powerful role in realising these future communities of sense, building social connections through artistic participation that emancipate us from the given universe of discourse and behaviour.

Art produces forms—words, spaces, rhythms, images, and so on—that allow us to act as if we already live in the future—making it clear that futures are not out there waiting, but manifest through creative and productive human labour and action. Artistic practice is uniquely positioned to create platforms that, in establishing variables for interaction, can make room for things in the public imagination that would otherwise seem too remote or amorphous. This anticipatory quality proposes a way of prototyping, of bringing new social and political forms into being.

Like the examples above, the alternate reality established through a narrative and imaginative vernacular, makes other things seem possible. With qualities of both the ordinary and the extraordinary, the sincerity of these prototypes provides a context where we can experience the viability, necessity, and normalcy of things that would otherwise seem shockingly foreign or unreal.

Creativity is a generative practice that, rather than totalising, encourages a proliferation of possibilities. Contemporary art practice plays with both the representational and the abstract, providing an outline where the details are emergent and contingent, allowing us to consider how we might bring something into being that cannot yet be represented because it cannot yet be imagined.

This page is part of UNHCR’s Project Unsung collection and portfolio. Project Unsung is a speculative storytelling project that brings together creative collaborators from around the world to help reimagine the humanitarian sector. To discover move about the initiative and other contributions in the collection, you can go to the project website here.