By Barbara Adams

Barbara Adams is a sociologist whose interdisciplinary research looks at how knowledge is produced and political action is initiated through art and design projects. Barbara co-edited the book Design as Future-Making and is co-editor in chief of the journal Design and Culture. She is Assistant Professor of Design and Social Justice at Parsons School of Design and was previously a postdoctoral fellow at Wesleyan University.

Generating Futures of Belonging

Empathy, helping, care, and resilience have been championed as strategies to repair our world and to renew and strengthen our relations with one another and with other living things. Yet, these approaches are less likely to transform alliances than they are to maintain existing conditions. The ideology of practice that guides humanitarian aid embraces these compassionate forms of helping along with an ethos of neutrality and impartiality, adopting an apolitical position that conceals how crises develop out of imperial and colonial legacies.

Moving from the inequity embedded in aid to the reciprocity and mutuality of solidarity would require disentangling a web of deep-set and seemingly immutable policies and practices. Storytelling, as a potent discursive force in shaping our perception of the world, can play a vital role in destabilising these views and the power asymmetries that characterise these orientations. Whereas some stories and myths establish and entrench dominant perspectives—maintaining and validating the way things are—others imagine alternative possibilities that reach beyond the given. In moving beyond the stories of damage, resilience, and heroism that characterise humanitarian aid, how might speculative storytelling based in solidarity play a role in initiating change and generating futures based in justice and belonging?

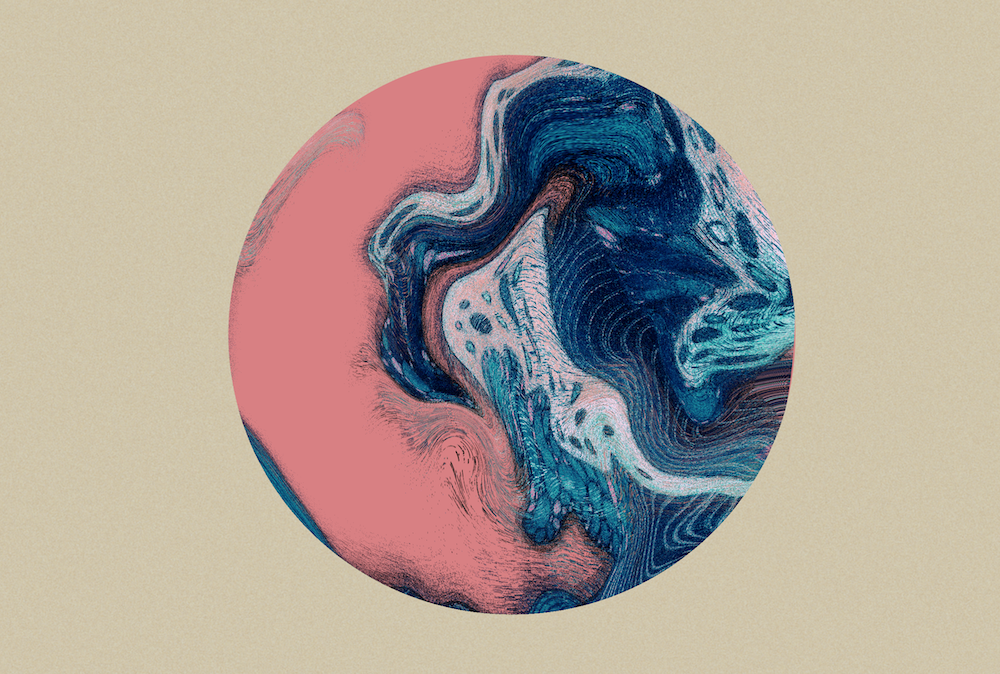

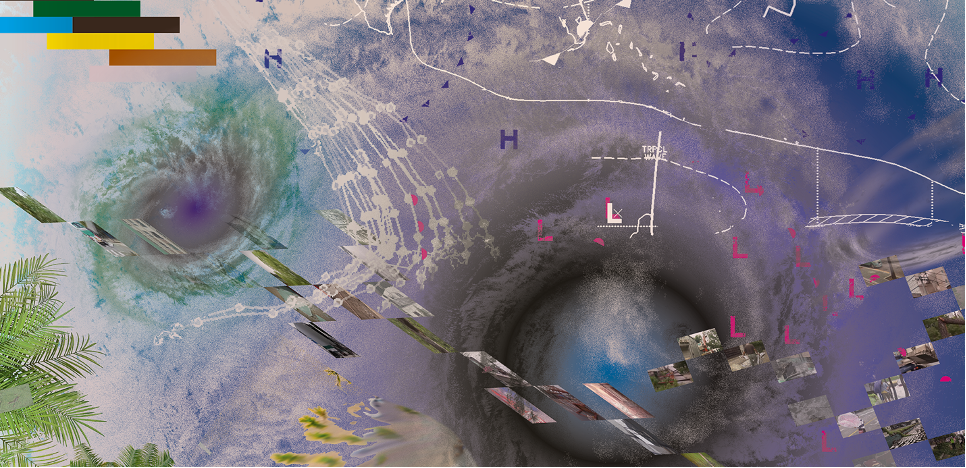

Haegue Yang’s Coordinates of Speculative Solidarity, from which this essay takes its title, understands extreme climate events not only as forces that fracture, but also as those that bind. This large-scale, digital collage, comprised of satellite photos, storm-tracking symbols, and palm leaves, maps the chaos of severe weather activity and explores how this, in necessitating alliances and interdependence, can prompt unusual forms of belonging and community. Crisis situations often create estuaries of concentrated and diverse stranger-based accumulations of people, and this heterogeneity along with the temporariness of emergencies, can both challenge and foster the formation of solidaristic relationships. In Greek, the term krisis (or κρίσις) marks the turning point in a disease resulting in either recovery or death. This inflection point provides the occasion for change where possibilities previously overlooked or occluded, might emerge. In upending taken-for-granted systems, crises rupture temporal continuity and our ideas of what is possible. These situations ask for something to be done. Responses aiming to alleviate the effects of crises range from help to mutual aid, and although these varying responses seem to have shared goals, they mark the difference between stasis and change, between triage and transformation. Crisis, as anthropologist Janet Roitman notes, is a narrative device that allows us to ask some questions while it forecloses others.

We are much more inclined to link crises to suffering than to solidarity. When witnessing suffering, we feel impelled to act swiftly to quickly alleviate distress. As the political theorist Hannah Arendt argues, this response, driven by compassion, addresses the immediacy of the situation but does nothing to alter the underlying forces.[1] Compassion, she points out, is a sentiment, while solidarity is grounded in reason. Whereas solidaristic relationships have sights set on an imaginative horizon of creating a different future, relations built on compassion obscure a view of transformation. With compassion, people exercise care, but they do not engage the wearisome processes of persuasion, negotiation, and compromise which are essential processes of political change. Hierarchies remain and divides deepen. Framed as ‘misfortune,’ we avoid reckoning with root causes. Those who suffer are seen as unlucky while those not affected feel compassion (or its perversion, pity) for those who are. Pity deprives people of their public, political identity. It is only out of solidarity, that communities of interest can be deliberately and dispassionately established so they can meet as equals. Helping, in contrast to solidarity, does little to alter the status quo or to make significant changes to the ways in which power and agency are distributed on a structural level. As social scientist, physician, and former Vice President of Doctors without Borders Didier Fassin succinctly puts it: “the politics of compassion is a politics of inequality” where “domination is transformed into misfortune, injustice is articulated as suffering, violence is expressed in terms of trauma.”[2]

Beyond Empathy

Western culture commonly invites the ‘lucky’ to imagine and experience the suffering of ‘others’ through the use of empathetic technologies. That participation, in itself, can lead to action and social change is a widely held notion in design, humanitarian aid, and broader cultural platforms and there has been a proliferation of participatory activities that simulate crises. In Davos at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting, Refugee Run: A Day in the Life of a Refugee, one of the most popular events at the summit, simulates the experience of living in a refugee camp. Organised by the Crossroads Foundation, this exercise provides an embodied and immersive “x-perience” of daily life in a camp for displaced persons. The foundation’s website promotes the activity as a way for world and industry leaders to develop empathy (ignoring the ways in which they may be potentially complicit in creating crises): “Participants face simulated attacks, mine fields…hunger, illness, lack of education, corruption and uncertain shelter or safety. Participants may also be marched under guard, subjected to ambush and, ultimately, offered a chance of re-settlement where they must re-build their lives.” Actors in military costumes storm the room while elite CEOs and executives cower on the floor, reacting to an experience they are unlikely to ever encounter in their daily lives.

These simulations leverage role play as a tactic in understanding the plight of the misfortunate, asking participants to occupy the status of the other. Simulating the experience of a refugee camp, the journeys and arrivals of displaced people, and militarised challenges to citizenship and belonging is a surprisingly common motif. Although well-intentioned efforts that aim to generate empathy, it is absurd to think that the persistent uncertainty, loss, and fear that accompany displacement could be captured or conveyed through these activities. Even if these efforts succeed in generating feelings of empathy, what sorts of relations emerge from this emotion? Can empathy move us from caring about, as a sentiment, to caring for, as action? Can it move us to a position of caring with, where we act together to address the ways in which we are all implicated in the complex issues that more deeply entrench systemic inequities?

In these cultural projects, the lives of actual people are typically flattened and assigned a generalised profile that cannot provide the basis for solidarity or meaningful association.The rhetoric that aid and protection help rebuild lives shattered by unfortunate circumstances fails to acknowledge how this form of support also reduces the unique complexities of people’s lives. This might be dismissed as unimportant in emergency relief contexts, yet it is in these settings where people most need to be seen and heard and recognised. The erasure of complex personhood is a byproduct of humanitarian aid—something that holds true for both those who provide and those who receive aid. While beneficiaries are often reduced to their suffering, stripped of their public and political identity, and positioned as noble sufferers, the humanitarian, as a delegate, is elevated to the position of an oracle or hero. This dynamic involves a transfer of power, establishing a relationship of reliance. As sociologist Pierre Bourdieu notes, “the more people are dispossessed…the more they are constrained and inclined to put themselves into the hands of representatives in order to have a political voice.”[3] A delegate or representative is often necessary for a group to articulate its position—yet speaking in place of someone always involves symbolic violence, no matter how elegantly this is exercised. Speaking on behalf of others is a flawed theory of change that maintains the status quo and acts as a barrier to transforming underlying conditions.

Complexities of Care

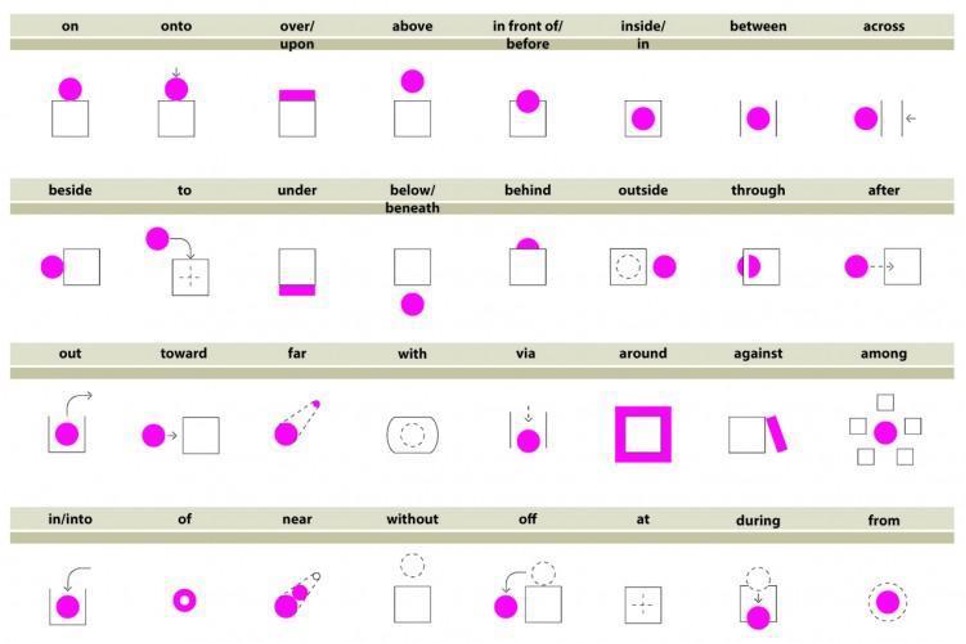

Recent calls to put care at the centre of life ask us to “acknowledge the challenges of our shared dependence as human beings—as well as our vulnerability and irreducible differences.”[4] Care, depending on how it is understood and enacted, operates on a spectrum and can be an expression of compassion, an act of solidarity, or something in between. For example, the anthropologist Miriam Ticktin shows how regimes of care demand that migrants and displaced people foreground their suffering in order to be heard, becoming “casualties of care,”[5] subject to paternalistic forms of protection. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, unpacks the varying dimensions of care as moral obligation, as maintenance work, as a tool of oppression, and as vital politics, noting: “To care can feel good; it can also feel awful. It can do good; it can oppress. Its essential character to humans and countless living beings makes it all the more susceptible to convey control.”[6] Feminist thinkers Joan Tronto and Bernice Fisher, characterise caring “as a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue and repair our ‘world’…[as] a complex, life sustaining web.” In this understanding, our inevitable interdependency, as a condition of living together, is simply a fact—something that cannot be quantified or denied. It would be impossible to evaluate (although surely people have tried) how much we need other beings, whether human or nonhuman. This notion of care departs from compassionate forms of caring about and from aid-based models of caring for, in favour of the mutuality of caring with.

Barriers to Change in a Shifting Landscape

In actionable terms, this shift in prepositions from caring for to caring with, is not easily accomplished. In the context of humanitarian aid, the barriers to change are formidable. Meaningful and deep transformation jeopardises the very existence of humanitarian organizations since aid is contingent on a relationship of inequity. Hierarchical power permeates all scales of aid organizations and the labour of socially reproducing this unequal structure is embedded in aid work itself. This is evidenced, for example, when aid organizations celebrate their longevity. The perversity of this is only recently being recognised–notably in an op ed from UNHCR’s High Commissioner, Filippo Grandi where at the close of 2020, on the 70th anniversary of the organization, he challenged the international community to put him out of a job: “Make it your goal to build a world in which there is truly no need for a UN refugee agency because nobody is compelled to flee.” In another example, the World Humanitarian Summit called on aid organizations to: “recognise that affected people are the central actors in their own survival and recovery, and put them at the heart of humanitarian action. This requires a fundamental change in the humanitarian enterprise, from one driven by the impulses of charity to one driven by the imperative of solidarity.”

Yet, in spite of these recent outliers, shifting the existing culture and power asymmetries appears insurmountable. With an organizational culture that is resistant to change), efforts for transformation are met with incrementalism at best. Although the humanitarian sector may easily embrace new technologies and tools, these forms of innovation leave the underlying infrastructure intact, and avoid challenging the entrenched structures and assumptions upon which aid operates. Perhaps the most innovative path would be to address these structural issues and commit to their repair.

Imagining and Forging Solidarity

In Emergent Strategy, adrienne maree brown positions the imagination as one of the spoils of colonialism where the few imagine futures for all. This results from exclusionary practices and reflects broader social inequities where some groups are not afforded the autonomy, time, or agency to contribute to collective imaginaries. In avoiding difficult but rewarding negotiations across difference—those that address deep seated and taken-for-granted hierarchies—we miss opportunities to connect around shared interests, not just in struggle but also in ways that are joyous.

We imagine that connection across differences is more difficult than relating to those we perceive as similar to ourselves, seeing the world through the lenses of “here” and “there,” “us” and “them.” Our inability to imagine a common horizon of action also involves a question of scale. Two dominant tendencies, according to Jodi Dean, obscure our capacity to engage in struggle for a common project: survivors and systems. In the first, individuals struggle to survive, fighting unassisted against the odds. Based on the values of resilience and self-reliance, people become mired in the pain and trauma of their struggles. Fighting for their individual survival, they are unable to grasp or transform the conditions in which they find themselves. In the second, the vast and complex nature of systems leaves people overwhelmed and unable to act as they lose sight of the local and the specific. Dean poses solidarity as a middle ground enabling us to recognise the necessity of interdependence in responding to situations that would seem daunting if faced alone.

To what degree are humanitarian aid workers able to create solidarity with the groups with whom they collaborate? Professional humanitarians define their work in terms of service to “beneficiaries”, while solidarians are guided by egalitarian and anti-hierarchical principles. In contrast to bureaucratic frameworks, those invested in solidarity emphasise (and importantly, practice) modes of collective association and recognition based in reciprocity. Whereas one model uses the language of suffering, the other uses that of liberation. On the one hand, practising solidarity—given its incompatibility—would necessitate the very demise of aid organizations. While on the other hand, power-sharing, collaboration, and distributed forms of collective agency are already active in these spaces as small-scale, sporadic, and disobedient alternatives to hierarchical social relations and Western styled humanism. These situations might be understood as what cultural theorist Raymond Williams calls “structures of feeling”—those rhythms and sentiments that hover at the edge of semantic availability. Having not yet realised their social character, they are positioned at junctures where society experiences changes in presence.

Solidarity has a speculative character and is fundamentally a horizontal activity with its focus on liberation, justice, and the creative processes of world- and future-building—projects that are never complete. The horizon is always present in the landscape, reminding us that there are things beyond what is visible from a particular location. As a coordinate central to perspective and orientation, the horizon is vital to successful navigation. As we move toward the horizon it remains “over there,” showing us that there are limits to what we can know in advance. However, rather than frustrating our efforts, horizons represent possibilities.

Speculative, Solidarian Storytelling

We speak very casually and confidently about humanitarianism, borders, nations, and so on as if they have always existed, and we imagine these structures will endure. This is a story we have been told. We make this durable, mythical even, in its regular retelling. Like any social construction, it takes on a material and enduring quality the more it is accepted as something real and unchangeable. How might we reimagine stories of stasis as those of transformation and metamorphosis by asking what else is possible? What do future stories of mutuality, interdependence, and belonging look like?

Speculative and visionary fiction offer alternatives to stories of dependency and structural vulnerability. In finding that precarious balance between hubris and humility, these modes, according to Walidah Imarisha, “imagine paths to creating more just futures.” In these stories, change is understood as relational, and transformation is led by those who have been marginalised, living at the intersections of identities and oppressions. In posing alternatives to how we live now, these stories, which centre people and are often communally generated, allow us to see, sense, and explore a world beyond that which is given. These articulations collectively practice and propose justice-based futures, and visionary fiction marks a sharp departure from the dominant Western template of the hero’s journey.

Monomythic narratives of the hero show us a path to inner transformation that does not necessarily involve (deep) social change. In this familiar trope, we follow the emotional, psychological, and physical journey of an individual who is called to leave their ordinary life to embark on a high stakes adventure. After some initial resistance and in spite of the risks involved, the hero eventually sets out on the journey, leaving home and the known. Although a relatively solitary endeavour, the hero normally encounters a mentor who assists in acquiring the necessary confidence, knowledge, and skills. Facing a series of tests with no possibility of turning back, the protagonist engages allies and enemies oscillating between failure and success. He (and although this might not be a “he,” it most often is) eventually triumphs and is reborn with a special wisdom and mastery of both the ordinary and special worlds. Upon the return home, he is welcomed as a victorious hero who has transcended to a higher plane.

The hero’s journey is such a common and familiar trope that we rarely question its logic. We identify with the alienation felt by the hero—estrangement from the self, from others, from nature, from the agency needed to change the world. We embrace the notion that suffering leads to redemption and personal resilience marks the path to expertise. The values embedded in this mode of storytelling mesh perfectly with the rhetoric of perseverance and individualism that characterise the bootstrap ideologies of capitalism and the paternalism and saviourism of colonialism. Individual change as a path to salvation confers deservingness. Although touted as universal, the monomythic hero’s journey is culturally specific, deeply rooted in the Judeo-Christian tradition. In the hero’s journey, precarity, vulnerability, fragility, and frailty are understood as individual shortcomings—something to remedy independently. Principles derived from the hero’s journey are evident in a range of fields from social work to urban planning to insurance to humanitarianism. In particular, there has been a growing preoccupation with resilience, a ‘virtue’ underscored in the hero’s journey. Resilience models ask individuals to bear the burden in adapting to stress, crisis, and adversity. In addressing the symptoms rather than underlying causes, resilience preserves the conditions that create hardship. In its reverence of personal grit and fortitude, resilience valorises individual achievement, pliability, expertise, and authority rather than collective efforts to institute structural change.

While hero narratives chart the conquest of adversity, damage narratives fixate on harm and injury as a way of achieving reparation. Eve Tuck, in “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” points to the oppression inherent in narratives based in deficit models that only document pain and suffering.[7] Singularly defining communities based on their distress pathologises and further inflicts injury, and according to Tuck: “Native communities, poor communities, communities of colour, and disenfranchised communities tolerate this…because there is an implicit and sometimes explicit assurance that stories of damage pay off in material, sovereign, and political wins.” In being reduced to victims, the subjects of these stories are diminished and objectified. They bear the burden of testimony with their lives reduced to determinant power relations. Tuck proposes a desire-based framework as an antidote to shift the focus away from damage to acknowledge the “complexity, contradiction, and the self-determination of lived lives…so that people are seen as more than broken and conquered.” Incomplete stories that underscore only pain and damage are, Tuck asserts, acts of aggression. Desire-based narratives focus on what Gerald Vizenor calls “survivance” which involves “active resistance and repudiation of dominance, obtrusive themes of tragedy, nihilism, and victimry.”[8] Whereas stories fixed on damage truncate the richness of actual lives and their futures, those based in desire generate agency and the conditions for speculating and dreaming.

By focusing on oppression and dispossession, stories that centre resilience and damage socialise people to act as either victims or as “privileged subjects who can afford to care about what is done to others, thus reproducing the radical difference between them, rather than as cocitizens who care for the common world they share.”[9] Ariella Aïsha Azoulay highlights the necessity of unlearning imperialism to move beyond helping and aid, “understanding that what was taken by the unstoppable imperial movement, and held as if naturally owned by Western institutions, cannot be parsimoniously redistributed through charity, educational uplift, or humanitarian relief.” Without repairing the profound and lasting effects of imperialism, she argues, there is no possibility of realising futures based in justice.

Like Azoulay, Ursula LeGuin understands the power of stories as forces active in reevaluating the past so we can build worlds and futures based in mutual care. Lived experiences are dense and complicated, with pasts, presents, and futures weaving complex patterns. LeGuin begins with the premise that our first cultural artifacts were containers and she celebrates “the carrier bag theory of fiction,” as an approach that “cannot be characterised either as conflict or as harmony, since its purpose is neither resolution nor stasis but continuing process.” These are stories that are “full of beginnings without ends, of initiations, of losses, of transformations and translations, and far more tricks than conflicts, far fewer triumphs than snares and delusions, full of…missions that fail, and people who don’t understand.” LeGuin offers a mode of storytelling focused on people going about their daily lives rather than those featuring heroes. Stories with heroes might be more gripping than the everyday experiences and negotiations that constitute the bulk of people’s lives, yet small quotidian actions provide the foundation for solidarity. The carrier bag theory has the capacity to encompass multiple worldviews simultaneously and can incorporate both human and nonhuman protagonists as significant actors.

In these stories, relationships are established that extend beyond kith and kin, leaving little room for saviours or victims. Grounded in human culture, people understand the necessity and delight of interdependence—a sort of collective effervescence where we desire to belong and enjoy welcoming others. The alien kinship and xeno-hospitality that characterise LeGuin’s fiction propose convivial futures. In pointing to the likelihood that the first objects humans designed were those for carrying, LeGuin speaks to the affordances of sharing and caring. With the capacity to carry things—from babies to seeds to water to curious and beautiful objects—people develop the ability to create futures that are interdependent and robust. In being able to carry things, we can collect more than we alone need so that we can share with others. Through sharing, we build and strengthen social bonds. Robin Wall Kimmerer extends this notion in her exploration of the ethic of reciprocity where nature teaches us how to share rather than accumulate. As a biologist and chronicler of North American indigenous stories, Kimmerer highlights how the natural world can teach us about mutual aid, recovery, and restoration. Through storytelling, she urges us to confront the dominance of systems that frame our world according to scarcity, instead focusing on abundance and “restorative reciprocity,” understanding that “all flourishing is mutual.”

What other forms of storytelling can guide us in recognising our interdependence, shifting power dynamics and fostering belonging? The discursive and performative power of stories can help in overcoming obstacles to collaboration, cultivating models of action that rearrange the coordinates that frame our understandings of the world—in its past, present, and future forms. Solidarian storytelling prioritises mutuality and justice over empathy and aid. Rather than maintaining existing conditions and their inherent power dynamics, stories of solidarity seek transformation through conviviality. This is something particularly salient in the realm of humanitarian aid where heroic myths, damage narratives, and tales of resilience dominate the discourse.

***

Strivings and failures shape the stories we tell. What we recall has as much to do with the terrible things we hope to avoid as with the good life for which we yearn. But when does one decide to stop looking to the past and instead conceive of a new order? When is it time to dream of another country or to embrace other strangers as allies or to make an opening, an overture, where there is none? When is it clear that the old life is over, a new one has begun, and there is no looking back? From the holding cell was it possible to see beyond the end of the world and to imagine living and breathing again?

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route

Only when home has vanished and humanity is no longer territorialised, only then, there will be a chance for humanity. Shahram Khosravi ‘Illegal’ Traveller: An Auto-Ethnography of Borders

This is the time to be unrealistic in our demands for change. We are told repeatedly we need to be realistic, but that is just another method of social control. We are told true liberation is an impossible dream by the powers that be, over and over again, because us believing that it is an impossible dream is the only thing between here and the new, just futures we want. Walidah Imarisha

[1] Arendt, Hannah. On Revolution. 1963. Penguin Random House.

[2] Fassin, Didier. Humanitarian Reason: A moral history of the present. 2011. University of California Press.

[3] Bourdieu, Pierre. La délégation et le fétichisme politique. 1984. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, 52-53.

[4] The Care Collective. The Care Manifesto: The politics of interdependence. 2020. Verso Books.

[5] Ticktin, Mariam I. Casualties of Care: Immigration and the Politics of Humanitarianism in France. 2011. University of California Press.

[6] Puig de la Bellacasa, Maria. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. 2017. University of Minnesota Press.

[7] Tuck, Eve. Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities. 2009.

[8] Vizenor, Gerald. Native Liberty: Natural Reason and Cultural Survivance. 2009. University of Nebraska Press.

[9] Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. 2019. Verso Books.

This page is part of UNHCR’s Project Unsung collection and portfolio. Project Unsung is a speculative storytelling project that brings together creative collaborators from around the world to help reimagine the humanitarian sector. To discover move about the initiative and other contributions in the collection, you can go to the project website here.