Part I

Letter from the editors

By Ann Christiano and Matt Sheehan, University of Florida, and Lauren Parater and Cian McAlone, UNHCR’s Innovation Service

It matters which stories make worlds and which worlds make stories.

Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble

Stories get told, and retold, and therein shape society and the mythologies around our identities. How are they opening up new lenses into the visible and invisible? At the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), we recognize how stories shape our organizational culture, our ways of collaborating alongside communities and alternative visions to how the humanitarian sector could be.

We also recognize that change is rarely straightforward, and a lack of institutional memory and historical assemblages can reinforce the status-quo. At UNHCR’s Innovation Service, we’ve witnessed how stories told around change and innovation have influenced the way people perceive and relate to creativity. We believe these stories are a critical tool for making innovation accessible to our colleagues, developing a shared understanding of innovation, and creating novel paths for our organization in solidarity with people who have been displaced.

If people in the humanitarian sector don’t see how much the sector has already changed, they can fall into the trap of believing that they can’t challenge current norms or values. If we look at the evolution of cash-based interventions in displaced communities, we can recognize a bright spot of what change looks like in practice. Not only has this shifted our emergency response, but cash-based interventions have challenged how the sector thinks about dignity and agency for displaced communities. Telling stories of change and innovation allows us to steward the organization towards alternative ways of being, knowing and acting. What stories do we need to tell to reimagine the power dynamics of our infrastructures, of local and community-based creativity, of plurality, solidarity, or possibility?

Storytelling and innovation should exist symbiotically through acts of experimentation and creation. They can be mutually beneficial to one another, influence our organizational culture and help us build the worlds we wish existed. Instead of an afterthought, let’s bring innovation to the forefront of how these stories are being told — highlighting the complex, in-between and incomplete stories that our organizations need to tell and hear.

We hope that this guide is the first step to better understanding how you might begin building the worlds and cultures you wished existed through storytelling.

INTRODUCTION

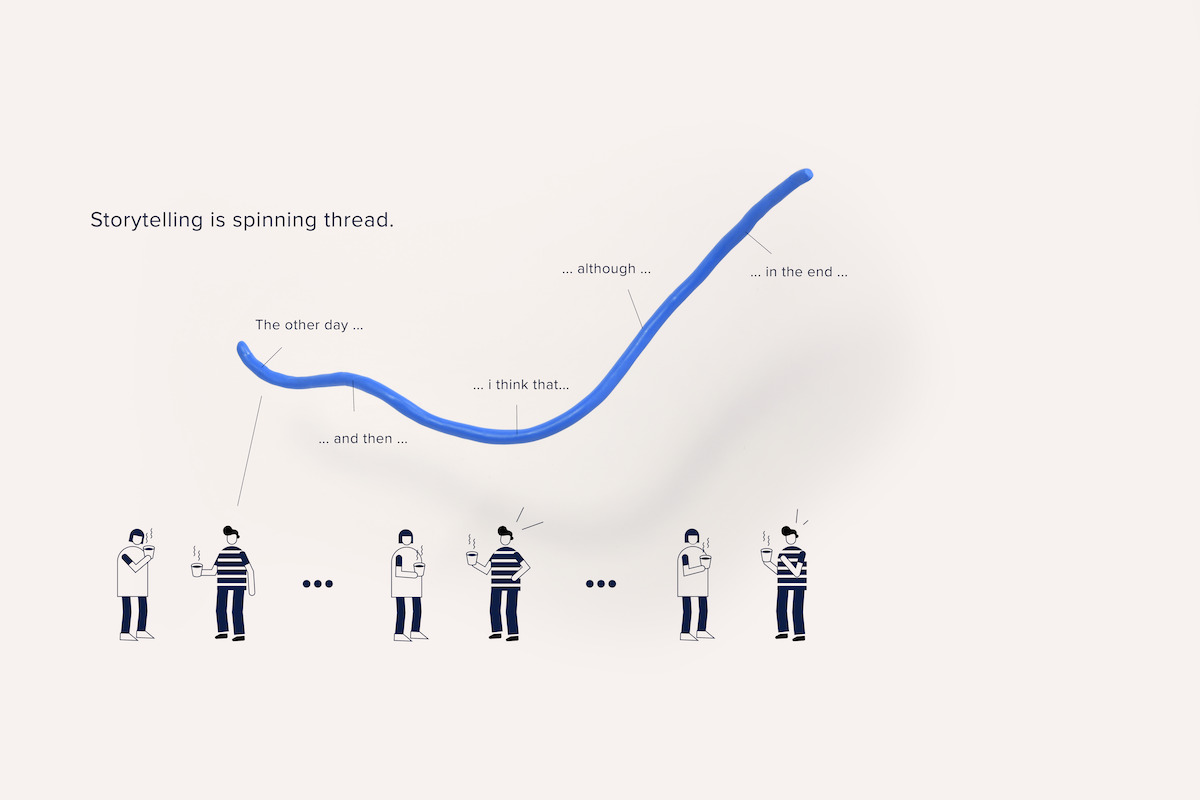

Every single one of us is a storyteller. While we often experience stories in ways that are highly produced by people who create and tell stories for a living—through our favorite television series, presentations, news, and documentaries—as humans we tell stories to communicate with those closest to us all day long.

Those stories we tell as part of our daily interactions can be as influential to people in your network as those that are more highly produced. They have the power to shift perspectives. Your catch-up with an old friend, those moments as you wait for colleagues to assemble for meetings, a venting session, or one-on-one meetings with your closest colleagues are all moments when you’re sharing stories.

Stories convey our sense of right and wrong, our organizational culture, our expectations of others, our worldviews and our fascinations. And because you are trusted by the people around you, the stories you tell can shape their perspectives on issues that matter to you both. Stories can help us gain and share new insights and perspectives, and form new ideas. The stories we tell signal who we see as allies and heroes, and celebrate behaviors we admire in others.

Stories are the vessels of culture, and culture is networked. If you want to change your culture, change your stories. Embracing your role as someone who both experiences and transmits culture within your team or organization requires intentionality about the stories you tell. Using story to transmit and shift culture isn’t just about being a good storyteller. It’s also about spotting good stories around you. You may also find yourself helping colleagues make sense of their experiences through story and develop narratives around their experiences and values. And you might push back when you hear others share stories that are harmful or untrue.

Storytelling isn’t always performative. This tool is focused on storytelling in its natural setting, the informal, interpersonal spaces where we build trust and transmit our expectations—the walk for coffee, the check-in, the venting session, the download after returning from travels. The term “storytelling” brings to mind TED-style talks, or people gathered at cafe-style events. But we tell stories every day, most often to audiences of one. Start observing the informal spaces and moments where people around you are telling stories. Share and spot compelling stories that will be effective in transmitting constructive behaviors.

The stories we tell and spot can capture the best of what the organization can be, transmit values, and celebrate courage and good decision-making. This guide includes resources for telling stories well in natural settings where we share them most often. It will also help you spot and cultivate great stories and challenge those that either reinforce harmful habits and norms or that aren’t true. It includes exercises and recommendations for practicing the principles and offering and soliciting feedback. It also provides exercises to help you hone your skills as a storyteller and spotter.

Compelling stories are fundamental to culture change. We may think of ourselves as experiencing the culture of the organization in which we work. But organizational culture isn’t simply experienced, we also manifest and build it through our collective behaviors. Countless studies have documented the role stories play in defining or shifting organizational culture. Stories are fundamental to building, reinforcing, or shifting organizational culture. The stories you tell new employees help them understand what’s valued or shunned. Those stories define culture and expectations. This is particularly significant in an organization like UNHCR where employees move through different roles frequently.

Now You:

Start listening for different types of stories at work. For two days, observe the stories you hear in your professional encounters, and use a chart like this to track them:

| Setting | Who told the story? | What was the story about? | Why did this person tell the story? | Which emotions did they show? | Which norms did this story communicate? |

| Waiting for others to join a Zoom call or Walking to the cafe | My supervisor, a friend at work, someone on my team | A recent breakthrough in their work | Because they were excited | Frustration shifting to pride, hope | Patience, determination |

Part III

Achieve positive culture change through constructive stories

The paradox of organizational culture. Your stories should transmit, reinforce and normalize constructive behaviors. The Uniqueness Paradox of Organizational Stories documented by organizational behavior scholar Joanne Martin in 1983 suggests that while every organization sees itself as unique, there are seven stories that form the basis of most organizational culture and gossip.

These stories include:

Rule-breaking, in which a low-status person holds a high-status person accountable to rules for the good and safety of the company, and is usually celebrated rather than fired.

Is the boss human? In which a high status person either does—or doesn’t—show kindness and equality with lower status employees.

Can the little person rise to the top? In which a low-status person with will and drive moves up quickly in the organization. But sometimes, in these kinds of stories, the person remains unrewarded.

Will I get fired? These are stories in which those in positions of power either go to great lengths to avoid firing employees or callously let people go.

Will the organization help me when I have to move? In which an employee moves multiple times to support the company, often at great personal cost. One version of these stories shows the support the employee receives. In another version, the employee’s personal costs are disregarded.

How will the boss respond to mistakes? In these stories, someone makes a mistake and is held accountable by their boss. In one version, the boss supports them, despite the mistake, in others, the employee pays an unreasonably high toll.

How will the organization respond to mistakes? These are stories about obstacles employees at any level in the organization face. According to Martin, these stories are by far the most common. They end when the obstacle is overcome, or it becomes obvious that the obstacle can never be overcome.

The stories that Martin lists are naturally occurring stories within an organization. It’s useful to have this list, because you could use it to begin to think about how you might listen for and tell true, compelling and constructive stories within each of these schemas.

Here’s another set of useful stories. Peg Neuhauser, in her now out-of-print book, “Corporate Storytelling and Lore” identified a different set of stories that define organizational culture and values. She calls them the “sacred bundle” in reference to the nomadic tribes of the American plains who carried a leather bundle of sacred objects that they would take out each night as they gathered around the fire. Each object in the bundle represented a moment in the tribe’s history that was sacred to their identity. They include:

How we started. How we started stories can tell the story of how your organization or unit began. These are powerful stories that can demonstrate the problem that needed to be solved before your organization or team was in place. Because these are “why” stories, they present an opportunity to connect with others’ moral values. For example, if your organization was founded to solve a problem they see as wrong or unjust, you can connect your mission to their values.

Our people. Our people stories share the experiences of extraordinary colleagues, whose skill or commitment demonstrate the organization’s deepest values and identity.

Why we do what we do. These can be stories of success or failure that motivate the organization to keep working toward solutions. They are most successful when they are about a single person.

What we learned in defeat. Failure stories are powerful for a range of reasons. One is that because they’re rarely told, they offer novelty. They offer an enticing behind the scenes look we don’t often have the opportunity to experience. More importantly, telling these kinds of stories in the organization can normalize experimentation.

How we succeeded. These kinds of stories are common, but they’re not useful for culture change when they are built around a single hero. They’re effective when they include people or systems that are often left out of narratives.

How the world will be better after we succeed. These are stories about how the world looks after you’ve met a need or solved a problem. They’re useful in offering hope, and providing a map that can make the change you’re working to create seem smaller and more manageable. These are the only stories that it’s okay to make up—although they should be rooted in what you know now, and what you’ve articulated as your mission or theory of change.

Now You: you’ve learned three sets of stories—the seven basic plots, the uniqueness paradox and the sacred bundle. Take some time to reflect on the constructive behaviors you’ve observed. What does it look like when people are engaging in these behaviors? Remember that list of stories you compiled in your two days of observation? Pull it out and review it against these three frameworks. Which kinds of stories did you hear? It’s possible that your stories simultaneously draw on all three frameworks. An “overcoming the monster” story can be a “how we succeeded” story, and a “will I be fired” story all at once. Thinking about them through these lenses may prompt you to add additional detail or characters that make them more meaningful and effective, but also situate your story in the organizational context and systems.

One more point: your stories should be as inclusive as your goals. What makes your stories constructive versus harmful is guided by your values and goals. It’s useful to take some time to reflect on the values you want to uphold or transmit through constructive storytelling. Review your story carefully for harmful tropes, a missed opportunity to describe the systems that lead to the problems you’re trying to overcome, or racialized language that may uphold or contribute to harmful stereotypes. If you’re telling a success story, ensure that all the people who contributed to that success are included in the story. And always look for ways to create space for people who have experienced marginalization to tell their own stories.

Part IV

You have to practice

Becoming an effective storyteller starts with observing the different places and circumstances where you hear and share stories. Your day might begin with the stories you read on your favorite news site. When you log in to your first conference call of the day, your colleagues may tell you a story of something that happened the day before, or the highlights of the show they’re binge-watching.

Storytelling is as much a part of our days as drinking water and breathing. But because we tell and consume stories as a way of achieving other actions like connecting with colleagues, teaching others, being entertained, or learning, we may not always see the stories themselves.

Here are some of the contexts in which you’re already hearing or sharing stories:

As part of presentations

As part of “venting”

To illustrate key points

In casual conversation

As part of evaluations and after-action review

Once you watch for them, you’ll see them everywhere.

Being an effective storyteller also means you have to practice telling them all the time. Once you acquire the habit of listening for others’ stories, begin to practice and experiment with constructive stories in these contexts:

Build a habit of using stories to make a point. Tying stories to your central point makes the “why” behind your perspective more memorable. You may do that naturally, but if you have time to reflect or prepare, think about these points:

Determine which type of story you’re telling, using the seven basic plots, the uniqueness paradox and the sacred bundle.

Consider which organizational or behavioral norms you’re speaking to. A norm is an expected or usual behavior within a specific community. If you’re telling a story to encourage the thoughtful consideration of risk as part of decision-making, you might try to reinforce a constructive norm by telling the story of someone in a leadership role who changed her mind after intentionally consulting someone with a different perspective. If the story is about someone else demonstrating a constructive norm, articulate why you find that person’s actions admirable and helpful to the entire organizational culture.

Bring us into your story. People often wonder how to bring stories into informal conversations naturally. One of the worst ways to do that is to say, “Let me tell you a story.” Instead, you might transition in conversation with a question that drops us into the middle of the story, right in the central character’s moment of uncertainty. As much as possible, you want your story to work seamlessly into the conversation you’re having.

When you’re telling stories to drive organizational change, it’s especially important to include systems as characters. That means including specific details about the existing systems—like hiring, assignments, or sourcing materials.

While some of the elements of your story may be mundane, the stories themselves have to be novel and fascinating. Here are some ways to do that:

- Introduce and humanize the narrators—give listeners insight into who the characters are.

- Explain the challenge the central character was faced with—the day-to-day realities for the most impacted—whether it’s the character themselves or the communities the person serves)

- Identify the moment when the character realizes they can do something different.

- Look for ways to make the system a character in the story. If you’re talking about public transportation, take the listener there with you.

As you practice telling more and more stories, think about the following:

Tell the truth. Your credibility is formed by the stories you tell. The most effective change stories have to be entirely true. No composites, no hypotheticals, no fables.

Keep your stories pithy to respect your colleagues’ time and their gift to you of their attention. As you work to tell increasingly effective stories, sometimes less is more. Work to shed every unnecessary detail and plot twist.

Keep your stories relevant. Your stories should provide value to the conversation or setting.

Choose the right emotions—sometimes it’s more powerful to tell stories that activate underutilized emotions like pride, hope and awe. Pride and hope motivate people to act, and show a path forward. When people experience awe, they experience a feeling that time has stopped. Once that happens, research suggests they are likely to become more generous with their time and resources.

And don’t be that person. Some things to avoid:

Stories in which you are the hero

That seem to project moral superiority or take the tone of preaching

Stories with cliché setups or predictable endings

That lead people to feeling emotionally overwhelmed or helpless

That reinforce harmful behaviors as a norm.

Part V

Help the people around you tell better stories

Spotting, coaching and pushing back

Now that you’re a master storyteller, you can also help others master these principles. It’s also true that coaching and supporting others is a useful way to strengthen your own skills. In this section, we’ll focus on how you can help others tell more interesting, complete and inclusive stories.

When you hear what sounds like the kernel of a great story, you can use these questions to tease out something even more compelling. These questions are particularly effective for people who are sharing their own experience. Moments of uncertainty can be the most compelling aspect of any story—but getting at them can be hard. The questions can help bring the storyteller back to those moments before they knew how their own stories unfolded, and help take others there as well.

Finding uncertain moments: “After you decided you were going to make a difference, what worried or scared you? Where did you think you might fail?”

Finding transition or glimmers of hope: “When was the first moment you realized that you were making a difference?” or “How did you get there?”

Capturing success: “How do things look now?” “What does it feel like to have succeeded?” or “What does it look like when you’ve succeeded?”

Identifying calls to action: “What’s left to do?” or “Whose support do you still need?”

Some other things to ask that can help others tell stories that transport people are, “What are the visuals in this story that will make us feel the same urgency that the characters do?” Or more simply, “What did you see as this was happening?”

What about when you hear a story that is harmful or that you suspect is untrue?

As you become a stronger storyteller and spotter, you may find yourself hearing stories that uphold harmful norms or stereotypes, or that may not be completely true.

If you’re hearing the story in an informal setting, one of the best ways to help the storyteller is to suggest that they consider the story from the perspective of another character in the story—perhaps someone who had less control over the outcome. If you suspect the story is untrue, you might share an alternative version of the story with the storyteller that you’ve heard elsewhere, and ask why the two versions might be different. When you find yourselves in these situations, asking questions that help people recognize the harm in the story for themselves is more effective than calling them out directly.

Part VI

About

Adopting a storytelling strategy for culture change requires two important shifts. The first is to build and nurture an environment in which stories are the common means of communication, particularly in informal and verbal settings. The second is to recognize the role stories have in communicating and reinforcing organizational cultural norms and expectations, and to use them to help others see what the culture you want looks and feels like.

As someone who not only experiences the culture of your team and organization, but who builds it too, the stories you celebrate, tell and repeat can have great power in building a culture you want to work in. Be deliberate in the stories you tell. Tell stories that celebrate inclusive work that upholds the mission of the organization, or that challenge harmful behavior and its consequences. Help others do the same.

About the partnership: The Storytelling in the Wild publication is part of a partnership between the UN Refugee Agency’s Innovation Service and the University of Florida Center for Public Interest Communications. In an effort to move past communication strategies that simply “raise awareness” of an issue, this partnership aims to connect those working in the humanitarian sector with applicable insights from behavioral, cognitive and social science to make a lasting difference on the issues that matter most and to harness the power of storytelling as a tool for social change.

A Few Additional Resources:

The importance of storytelling for new hires: https://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/amj.2014.0061

The importance of storytelling for organizational change: