Don’t start with a boat. Don’t show it lurching on the waves, a crush of terrified people packed elbow to ribcage, a baby crying. Don’t focus on their past: the homes they left, the loved ones lost, the bribes paid, the calculations made and agonized over.

Instead, let Shahm Maskoun, a 28-year-old refugee from Syria tell his story. He doesn’t just enjoy talking about his journey. He feels absolutely compelled to. To offer the world a new refugee narrative. To show what is possible.

“The real crisis right now is that the media and politicians are focusing only on negative examples,” Maskoun says. “Refugees are not the crisis. This is the crisis.”

Maskoun was a privileged but average young man in Syria before the war broke out. His father owned an international jewellery business in Aleppo and his mother was a professor of Arabic. He’d already completed his engineering degree and his siblings seemed poised to follow in his footsteps: His sister studied biological engineering, his brother electrical engineering, and his little brother was acing his ninth-grade classes.

“I had everything that I needed,” Maskoun says in fluent English. “I had my education, I did my engineering in one of the best universities, I had my car, my friends, the little house I thought I’d get married in one day.”

Then, suddenly, he didn’t.

Gone was the family business, and the new business centers Maskoun was helping his dad set up. The house. Too many friends and loved ones to think about. And Maskoun’s confidence that he could live in freedom if he lived at all, since he faced the choice of being conscripted for one warring side or another. He had already faced torture, something he only speaks of as “a black chapter in my life.”

It was a clear choice: kill or be killed. Maskoun could not stomach either option.

The Maskouns fled Syria and made their way across borders and nations, mercifully safe and eventually together in Marne-la-Vallee, a town on the outskirts of Paris. It was a fantastic opportunity for a refugee family. The vast majority of Syrian refugees ended up in neighboring countries like Jordan. Many others got stuck in a country as they tried to navigate tightening borders and policies dictating where they could and could not go. Others found work, licit or not, and were hesitant to give it up and move on.

By being granted asylum in France, Maskoun had a chance to start a new life. But at first, it was hard to feel anything but lost, and lonely.

“The refugee is a broken person when he arrives in a new country,” Maskoun says. “Especially when he finds himself not understanding what’s going on around him, not understanding the culture, not able to go outside to buy some bread or drinks. No connections.”

Maskoun did not speak French and had no friends in town. Depression plagued him along with his sad memories of friends lost, and a life interrupted so completely. He felt like a child who was struggling to understand the world around him.

He was also up against pernicious stereotypes faced by many refugees. The belief that refugees come to other countries to take people’s jobs, and collect welfare checks. That they show up for government handouts and don’t pay any taxes. That they are lazy. That they are extremists.

Right after Maskoun arrived in France, he did take. He used the support offered by the government to learn French. He accepted the small daily allowance for a few months before an academic scholarship kicked in, and the health insurance offered to all refugees and French citizens alike.

But Maskoun’s drive to develop himself kept him resolutely moving forward, and away from outside assistance. He enrolled in a master’s program and fine-tuned the French he’d picked up on the street. When he had trouble understanding the lectures, he recorded them, and played them back at night.

Shahm graduating from Université Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée in 2014.

Soon, Maskoun started to give. He made friends and invited them to his home to eat Syrian food and learn about the culture and history of his country. With his ever-stronger language skills he started tutoring his French classmates in their science courses, and invited them over for study groups. When he was recruited for an internship and later an enviable job as a project engineer for an international banking system, he always looked for ways to extend opportunities to former classmates he knew deserved them. He paid his taxes, and he got involved in political life. He taught math and physics to refugee kids for free.

“They call me refugee, but I consider myself a guest,” Maskoun says. “I had been very, very well welcomed. I tried to chase my opportunities to prove that I deserve what (France) gave me as security, as an educational opportunity and as equality.”

Two master’s degrees and a French identity card later, Maskoun is giving back in even bigger ways. He lent his experiences and talents to a program called Wintegreat to address just a sliver of the refugee crisis as he sees it: young, ambitious refugees who are newly arrived and need help to continue their educations.

The program works in some of the best business schools and universities of France to integrate young refugees who want to continue their studies but need a boost to do so. During a four-month course they learn French, study French history and culture, and receive weekly mentorship to help craft polished resumes and cover letters. Maskoun, who works in international development for the program, helps match the students with professionals in fields that interest them, and works with them to find internships or complete applications for higher education opportunities.

Students must be 18 years old and have completed high school in their home countries, though many have already started college by the time they arrive in France. They are screened and selected based on an initial interview, where Maskoun and his partners try to get a sense of their stories, objectives and motivations. They follow up with the students every month to make sure they’re on track and doing well.

“The main challenge is that when we meet these refugees, they are all motivated, they know what they want to do, but they don’t know how to do that,” Maskoun says. “I met a refugee who wanted to be a doctor. He knew that. But he didn’t know how to be a doctor in France. He didn’t know who to contact, how he should apply, how to transfer his certificates, where he could live in France and earn money… Those are the main questions and issues at the beginning.”

In the past year and a half, the intensive springboard program has integrated 150 students in Paris and Lyon. This fall, four schools are expected to offer courses to 500 more refugee students, from places including Sudan, Russia, Iran, Nigeria, Tanzania, Afghanistan, Iraq and Palestine. Companies are now contacting Maskoun with offers of financial support and internships or site visits.

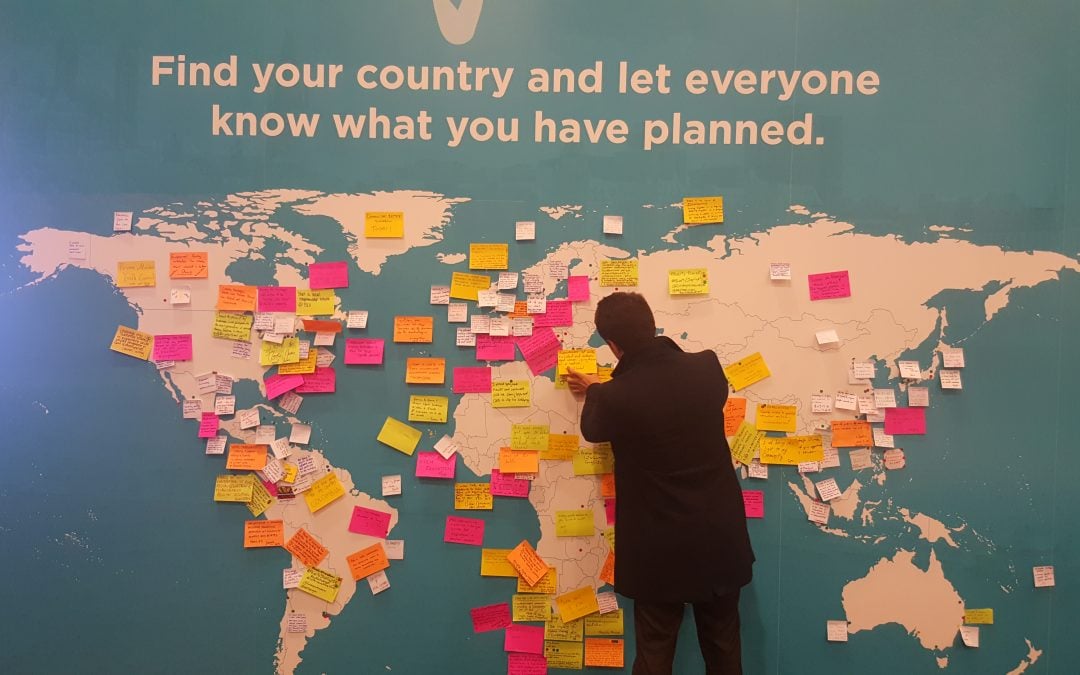

Maskoun acts as ambassador for the program, traveling around Europe and even representing Wintegreat at the One Young World Summit in Ottawa, where he spoke about the right of education for refugee youth.

It’s motivational for Maskoun. But one of the parts he likes best is at the start of the program, when he first gets up in front of the students, eager and anxious.

“I start my lectures in French so they think I’m a French person,” he says. “Then I switch to Arabic, tell them my story, tell them I was in their place, didn’t speak French, got two masters, learned the language, got an amazing job. I inspire them and give them this positive example to motivate them…”

“The main thing we try to work on is to empower those refugees, and make them believe in themselves and that they can do it again,” says Maskoun. “They are here, they are alive. With some effort, they can do it again. We tell them their first responsibility is to France, the country that took them in. The second is to their own country, to gain skills to take back.”

He also wants to show Europeans that they should be viewed as people, not a crisis. With a little effort on everyone’s part, they can be a value added to society.

He wants to combat those assumptions about refugees that he’s heard expressed even by his own school friends or co-workers. Since Maskoun’s French is so perfect and unaccented that he’s usually mistaken for a native speaker, people don’t think to stop themselves when they blame refugees for France’s unemployment, big social welfare expenditures, or even problems with terrorism.

So now, Maskoun talks. He shares his story with his colleagues. He goes on French radio and television stations, posts to social media, even gave an interview to a Financial Times reporter interested in his story.

He spoke at the French Ministry of Education, where he presented the work of Wintegreat and told his own story, explaining the problems refugee students faced upon arrival in France, and offering solutions.

“I try to broadcast what I can do as a person and to give a positive example to show people we are something, we are just like you,” Maskoun says. “We lost everything, what we need is just a little opportunity to prove that we can add value.”

How many Shahm Maskouns are there in the world? He argues he’s not exceptional, scrolling through his Facebook feed to show off similarly successful refugee friends. Those in the U.S. who’ve become doctors, the ones with satisfying jobs in Germany and Spain, the acquaintance who landed a position with the government of Turkey, the others who’ve started their own businesses.

Maskoun’s brother is working in mechanical engineering. And his little brother? He’s a success in a way no one might have imagined, as a YouTube and social media comedian with more than one million followers.

“I tell them no, I’m not an exception,” Maskoun says. “I’m an exception for you, because I’m the only one you know in this situation.”

“Try to find others,” he dares. “You will see.”

Maskoun feels at home now as he walks through the streets of Marne-la-Vallee. He feels that France is his country. And it is. He travels a lot for his work and every time he’s gone for more than a week he misses this place: his house, the winding side streets and broad avenues of Paris, the French language.

But he has not forgotten Syria. And although he is as much a part of French society as the next monsieur, he reminds himself that he is still a guest. Because someday, he hopes, he will return to his homeland.

Shahm at One Young World.

“I have been developing myself until today,” Maskoun says. “I’ve gained lots of skills, lots of knowledge … To be ready the moment it’s ready to go back to rebuild our country and just to take my part of responsibility when my country will call me.”

His is the new refugee story. Today around 65 million people seek protection in countries not their own. And whenever possible, they are making the best of it, trying to market their skills and learn new ones, find work and opportunity and make connections.

To Maskoun, and the sad, cliché refugee story he often sees in the media strips refugees of their previous successes, and their ambitions for the future. They make him feel guilty. Guilty that he couldn’t show the world what he has overcome and accomplished, the achievements he believes other refugees will surpass.

End with a success. Not a complete one, maybe. One that is still growing, and picking up speed. A success that demanded sacrifice, openness and acceptance. A success that gives others hope, and many pride.

We’re always looking for great stories, ideas, and opinions on innovations that are led by or create impact for refugees. If you have one to share with us send us an email at innovation@unhcr.org

If you’d like to repost this article on your website, please see our reposting policy.