A walk in the dark through Belgangi Refugee Camp

In February 2015, I was lucky enough to visit Belgangi Refugee Camp, Nepal at night. Where we left the car in a group the headlights, a streetlight, and lights in the medical center illuminated the space we occupied. We walked into one of the residential areas of the camp where the level of light dropped dramatically. I stopped to take a photograph of the warm glow coming through the walls of a shelter lit by a kerosene lamp and candles, and then one of the crisp white/blue light produced by LEDs powered from a small solar home system.

Soft light from kerosene lanterns and candles in Beldangi Refugee Camp.

When I looked up from my camera I was alone and it was dark, really dark. Instantly my sense of security changed. Rational thought said I was safe, but my reactive mind said otherwise. I can relate the feeling to hitting a big patch of turbulence in an airplane – a reaction in my brain says I am unsafe, that this is unnatural, that I’m about to fall 40,000 feet, yet logic says that planes are the safest mode of travel and that turbulence almost never causes airplanes to crash.

Crisp blue LED light and a very dark street in Beldangi Refugee Camp.

I could see little lights dancing in the dark and it wasn’t until these lights were a couple of meters away could I see that they were torches and mobile phones in the hands of refugees walking through the camp. When these people passed, their bodies shielded their lights, and they disappeared into darkness within seconds.

I found myself looking for light. I instinctively wanted to walk towards a lit area, but to do this, I had to walk through the dark. I was allowed to walk in this camp at night because it was safe and secure. But, in many refugee camps, walking through the dark to get to light could have had security implications.

Light and Protection; a complex relationship

Refugees consistently report access to light at the household and community levels as their top priority, followed by access to sustainable and appropriate fuels for cooking. This information comes directly from individuals and community groups, in refugee settlements in The Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

However, different communities comment differently on the impact of light and why it is fundamentally important to their lives.

For example, in Dollo Ado, Ethiopia, refugees communicate that household and community lights are important because they help expose snakes, wild dogs, and hyenas. Whereas in Damak, Nepal, refugees talk about the importance of light for reducing vandalism and theft. And, in Azraq, Jordan, refugees feel that without community level lighting, their life outside the shelter is restricted to daylight hours only.

These are no doubt important issues, but what about Sexual and Gender Based Violence (SGBV)? Access to light and the reduction of SGBV risks are commonly linked. The humanitarian sector links the reduction of protection risks as a prioritized rationale for the introduction of light. This link is supported by common sense and “natural” logic, which leads to the understanding that, for example, if a street is lit, people feel safer. And, refugees have consistently reported this.

This is clearly reflected in the Protection Risk Equation. Light, by definition is “something that makes things visible and affords illumination,” and when translated to the Protection Risk Equation can be used to expose protection threats and thus reduce protection risks. Conversely darkness can be used to hide protection threats and thus the increase of protection risks.

Protection Risk Equation.

Most dialogue around lighting interventions talk about light as a single unchanging thing, and that any amount of light as the above logic suggests should lead to the reduction of protection risks.

However, light can be used in many ways to influence security and social dynamics of a settlement at night. Different activities need different forms of light. For example, security lighting for streets and pathways need to cover large areas and, based on global standards, the level of illumination required is minimal compared to the type of light required to illuminate a marketplace or playground, which require high intensity focused light.

Think about how different forms of light are used in your life. For example, the differences between the type of light you experience at a McDonalds restaurant, compared to your local cosy coffee shop, or the differences between lights in a street at night and a floodlit football game.

Increasing Protection Risks – A Possible Consequence of Poorly Planned Lighting Interventions?

The humanitarian sector rarely assesses the diverse needs for light in a settlement appropriately and this can be linked to a significant gap often seen in funding community and street light interventions. As a result of this funding gap, as a sector, we have to prioritize where lights are placed, which is often done in an ad hoc manner without sufficient standards or guidance. However, how we prioritize placement critical and this process should be driven by communities in the field. If there were unlimited funding, lights could be placed along all streets and communal areas, negating the need for well thought through planning and prioritization.

The same common sense and natural logic used above can also be used to describe how the introduction of light into a settlement can lead to an increase in protection risk.

At night in a dark camp, where there is no lighting at the community or street level there is little incentive for people to leave their shelters unless they need to use communal latrines, which have been commonly and consistently linked with serious cases of SGBV.

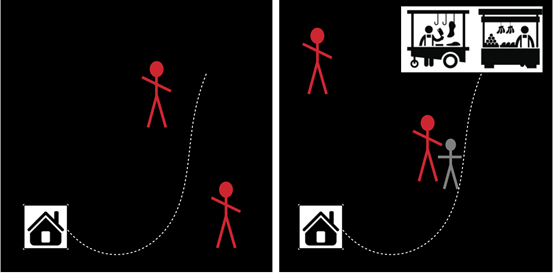

If light is introduced in a particular part of a camp such as a marketplace, health center, or community center, these areas are likely to become active at night. This naturally creates an incentive for people to leave their homes at night in order to access these illuminated spaces and the services they provide.

What situation does this create?

If lights are not located between someone’s shelter and the illuminated area(s) they want to access, they will be required to walk through darkness in order to access these areas and the services they provide.

As has been previously discussed, the exposure to darkness in refugee settlements has regularly and consistently been linked with an increase in protection risks through hidden protection threats, for example – especially SGBV.

How light can be an incentive for people to leave their shelters at night

In essence this creates a direct link between a poorly planned street lighting intervention and an increase in protection risks of an individual or community. This goes against one of the core principles of the humanitarian sector – do no harm.

This raises a tough but important question for the humanitarian community:

Should we move forward with lighting interventions that are not adequately funded and/or planned?

The above suggests we should consider saying no.

I think this argument alone should be used as a tool to communicate with stakeholders in the humanitarian sector considering implementing or funding light projects. It highlights the importance of, not only how light can impact refugee settlements, but the importance of carrying out lighting interventions in a well planned community-based fashion, and the possible implications if this is not the case.

The humanitarian sector should be aware that, based on the above arguments, funding part of a lighting project could impact the principle of “do no harm” if that project is poorly managed and monitored. As a result, donors should be asking more directly about the true lighting needs in refugee settlements and helping to fulfill those needs before requesting more directly the impact lighting interventions have on communities.

What do you think?

If you’d like to repost this article on your website, please see our reposting policy.