Feature: Bam's children on the upswing months after earthquake

Feature: Bam's children on the upswing months after earthquake

BAM, Iran (UNHCR) - Leyli, nine, is no pushover in the playground. She pulls the boys off the swing when she wants her turn, but she doesn't play for very long. After less than 10 minutes, she runs off to the side, where her grandfather is waiting.

"He is very old," explains the Iranian girl, "and when I play for too long, I am afraid that he feels very lonely, and very sad."

Leyli lost her parents when an earthquake hit the historic city of Bam last December, killing some 30,000 people. In the few weeks that followed, her grandfather would not let her out of his sight.

"It was very boring," she recalls. "There was nothing to do all day, just sitting in the tent. But now there is a school, and there is the playground. It is much better."

The playground in question is located in Vahad camp, a settlement of some 3,000 families whose houses were destroyed in the December quake. Most of the children here have lost a parent, sibling or friend.

In mid-May, the UN refugee agency officially opened the playground at Vahad camp, along with seven other playgrounds in Bam. All of them were funded by donations - close to $5,000 - from UNHCR staff in the aftermath of the earthquake.

"I am very proud and happy that thanks to the generosity of the staff, we have been able to build eight playgrounds for the children of Bam, who have suffered such a terrible tragedy," said Philippe Lavanchy, UNHCR Representative in Iran. "The playgrounds are a step in the right direction for these children who have lost so much."

The deputy mayor of Bam said he was extremely grateful to all UNHCR staff for their contributions. "I speak not only as deputy mayor, but as a citizen of Bam, who remembers the lives of the children before the earthquake, and in the few days and weeks after the disaster. Playing is a crucial part of getting back to something like a normal life for these children. I want to sincerely thank UNHCR staff for making this possible."

Sadly, Leyli's case is very common in Bam, according to Vahad camp's coordinator for the Society for Protecting the Rights of Children, a Ms Ahmadi. This Iranian non-governmental organisation is sponsored by Nobel Peace Prize-winner Shirin Ebadi, and has been present in Bam since the first days of the earthquake to help the children cope with their psychological trauma.

"After such trauma, it is normal for the surviving adults to want to keep the children close to them, to refuse to let them out of their sight," notes Ahmadi. "The shock is so great that people are terrified that they could lose more, and they become over-protective of the children."

In the weeks that followed the earthquake, the rescue effort was focused on saving lives, and providing food and shelter to the survivors. UNHCR contributed relief items, and deployed a team to coordinate assistance for some of the 3,300 registered Afghan refugees in Bam.

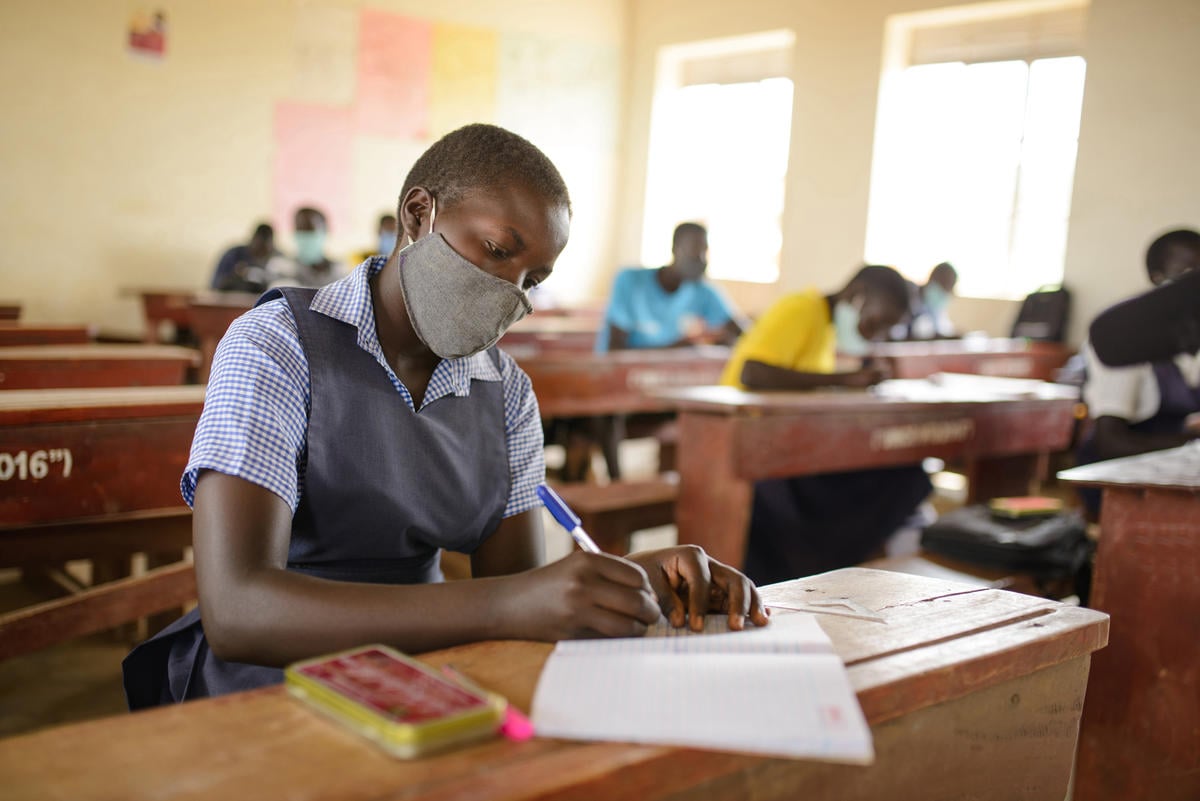

The needs of the children were not a priority, but the situation has improved now. Today, they attend school in large tents. Vahad camp also boasts a library, where children are encouraged to read, draw, or just talk with staff who have been trained to deal with trauma. There are even "happiness sessions", during which the children are encouraged to act, play music, dance and do anything they enjoy.

"It's very difficult for the children," says Ahmadi. "They see that the adults around them are very sad, and often they feel guilty if they are having fun. But of course, it is when the children are having fun that the adults can feel less sad."

Watching the children in the playground, it is hard to imagine that they have gone through such a tragedy. Their biggest problem today is getting access to the swings and slides, a turf battle that has divided the boys and girls.

"The boys are always aggressive," complains Massoumeh, 12, who has nominated herself as the girls' leader for the day. "They use their power all the time. But if they can use their power, so can we."

She negotiates with a group of boys for access to the swing, and when it doesn't work, she pulls one off to make room. Eventually, the situation resolves itself amicably, with each group agreeing to use the swing for 15 minutes before swapping.

A tiny five-year-old girl looks on quietly. She shakes her head when asked if she wants to go on the swing too. She is too small for the rough and tumble, but has worked out a unique solution for herself.

"I come here during the hot hours of the day," she confides. "I don't mind too much that it is hot, but the other children do. That way, I can play on all the swings, and no one bothers me."

UNHCR hopes that the eight playgrounds in Bam will allow some 17,000 children to play in peace again.