Xenophobic attacks drive hundreds from homes in South African suburb

Xenophobic attacks drive hundreds from homes in South African suburb

ATTRIDGEVILLE, South Africa, March 28 (UNHCR) - After months of sporadic xenophobic attacks elsewhere in South Africa, a series of brutal assaults on foreigners in makeshift settlements on the outskirts of the capital has galvanized government and private organizations into action.

The mob attacks this month on foreigners in Attridgeville - everyone from refugees and asylum seekers to South Africans born overseas - left several people dead and large numbers of houses looted and burned.

Nearly 500 people, including 140 asylum seekers, have been given shelter in a school near the Attridgeville police station. Numerous other foreigners have found refuge with friends and relatives. The UN refugee agency's local partner, Jesuit Refugee Services, is among the organizations distributing food.

"This was the first trouble I had here, I did not expect it," said a Zimbabwean woman who had been in South Africa for seven years. "They hammered open doors, some of them had guns. They took all my things. I was raising chickens and they even stole all of them."

In many cases of xenophobia in South Africa, the foreigners appear to be victims of jealousy - women and men engaged in small-scale trade who are perceived to be more successful than their local competitors. Often violence has followed mass protests against inadequate government services. But it was unclear what triggered these attacks, which began with a march by mobs that police estimated to number several thousand people.

However, it has followed several other attacks in the region around the capital and in the Eastern Cape Province this year - an alarming increase in xenophobia despite years of information campaigns by the government, UNHCR and non-governmental organizations calling for tolerance.

"UNHCR is deeply concerned by this loss of life and property among innocent refugees, asylum seekers and other foreigners," said Sanda Kimbimbi, Southern Africa representative for UNHCR. "These recurring xenophobic attacks have to be stopped and urgent action is needed from everyone, starting with South Africa's authorities."

In many previous instances, the mob violence and looting had been directed specifically against Somalis running local businesses known for their aggressive pricing. The attacks at Attridgeville, though, were indiscriminately against anyone considered foreign. They triggered a high-level reaction.

Minister of Home Affairs Nkosazana Dlamini, who is in charge of immigration and refugee issues, spoke to the community on Wednesday, condemning the violence. And the Municipality of Tshwane, which includes Pretoria, has taken the lead in organizing a three-prong reaction: better policing, immediate humanitarian assistance and reintegration of the foreigners into the community.

The foreigners, as in attacks elsewhere in South Africa, had complained of an inadequate police reaction and the failure to prosecute perpetrators. Police in Attridgeville say they do not have the resources to control mob violence but have promised to open an extra police post in the sprawling area of shacks.

The immediate humanitarian need is food, which is being met by a number of organizations, including UNHCR, but many of those driven from their homes have lost all their possessions. "Five years of work and everything was taken," said one woman sheltering at the school.

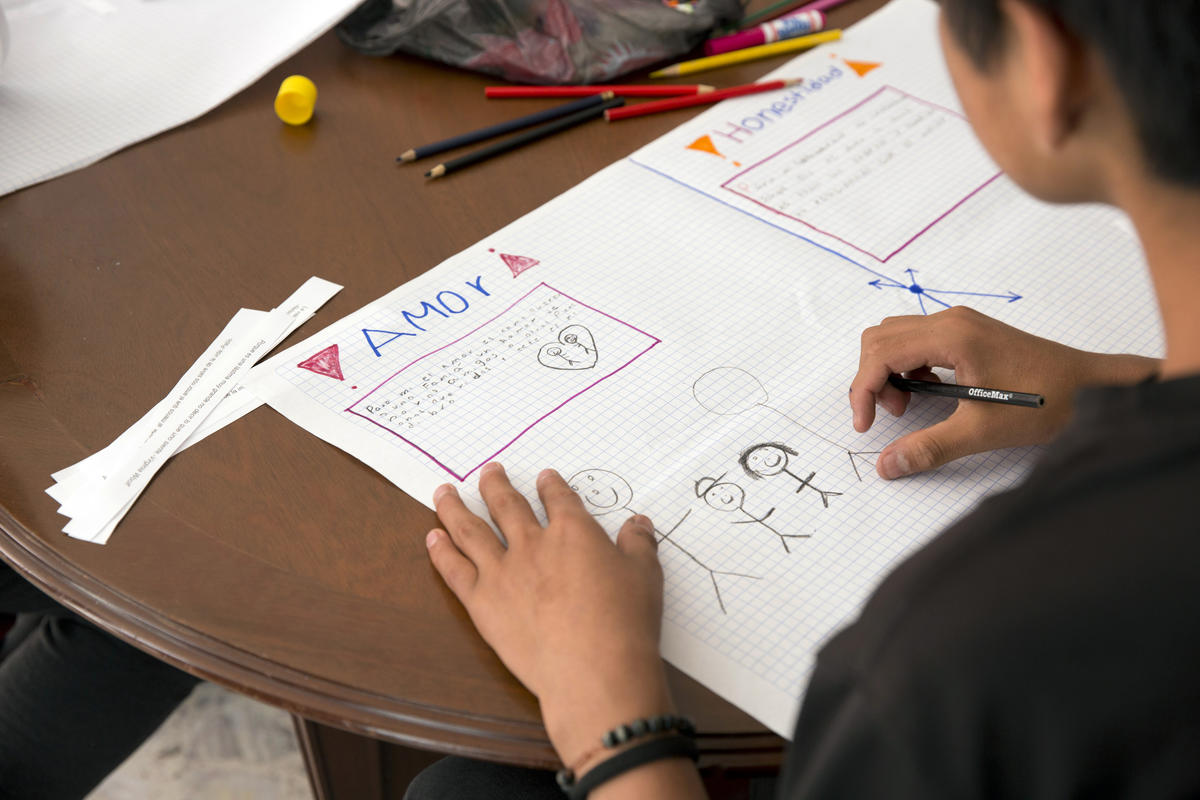

However, the biggest challenge is the goal of reconciliation and reintegration of the foreigners into the community. Teams including government, police, UNHCR, non-governmental organizations and - crucially - community representatives, plan door-to-door canvassing of the settlement to discuss the situation.

Key to this is a mass meeting due Saturday at which officials plan to announce that reintegration of the foreigners will start the next day. It will be a challenge, and not just because emergency housing will have to be provided. Contingency plans are necessary in case the goal of reintegration proves impossible.

"I think these people later on will kill us," said a woman who left Zimbabwe more than a decade ago. The fear is widely shared, reinforced by continuing reports that those who fled have been warned not to return.

The "informal settlements" - sprawling fields of shacks built from boards and corrugated metal sheeting - house South Africa's poorest people. They have also increasingly become home to foreigners, including refugees and asylum seekers, who are unable to afford the costs of even the worst areas inside cities. Some refugees have fled from one settlement, only to be driven out again.

"Things are bad," said a Zimbabwean asylum seeker who arrived in 2005, fleeing what he said was political persecution at home. "Now I am afraid to stay. Maybe I can flee this country."

By Jack Redden in Attridgeville, South Africa