Berhe once worked in hi-tech. But because his religion is illegal in Eritrea, he was jailed.

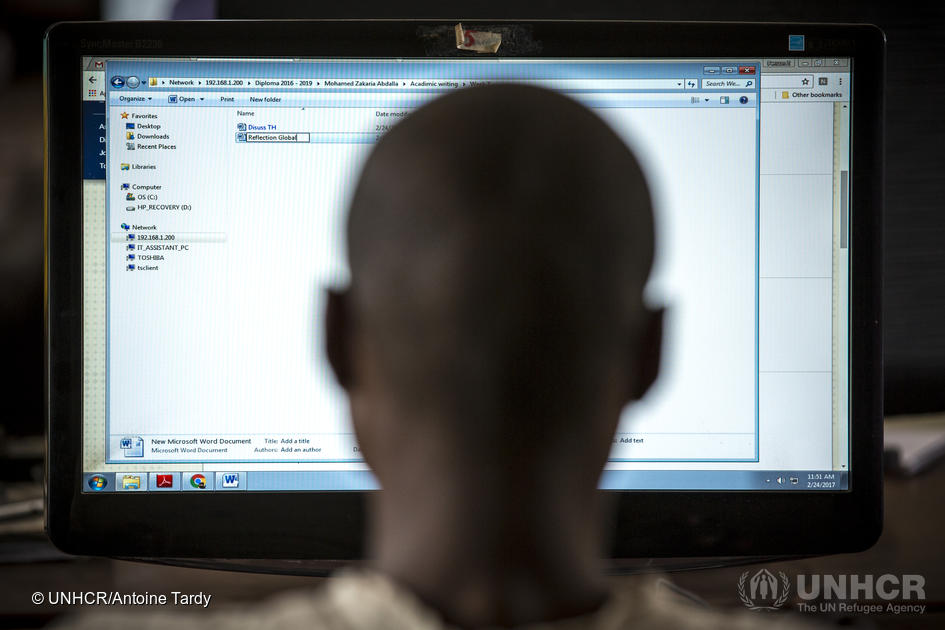

Berhe is a computer programmer who was withdrawn from university studies and jailed by the government because his religion, Pentecostal Christianty, is illegal in Eritrea.

When Berhe talks about Eritrea, his eyes fill with tears, not from a longing to go back, but from the pain and cruelty he suffered there. He refers to his homeland as a house without light.

“It is dark without end, our country. There is no vision for the future.”

Berhe, a trained computer programmer and member of the Orthodox Christian Church, was pulled out of university studies by Eritrean government security forces. They accused him of being a Pentecostal Christian, a form of Christianity which is illegal in Eritrea.

“After that they sent me to prison.”

For seven years, from 1999 to 2006, he was imprisoned, forced to serve in the army and work hard labour.

“I had to work like a slave while I was tortured severely.”

Throughout this time, he was unable to contact his family. He sent numerous letters to the government begging for his release, but he never received an answer.

“It was there where they took my fingernails,” he says, showing his fingers where the skin has grown over into a soft scar. “This is my country” he revealed, looking at his hands.

During this period, in 2002, Berhe became desperate to change his situation and tried to escape. While on the run, one of his friends stepped on a mine and was instantly killed. Berhe himself was injured and suffered burns that covered half of his body.

“The police came and sent us to the hospital… then back to prison.”

After four more years of imprisonment and hard labour, Berhe attempted another escape. This time, he made it across the border into Sudan and then to Egypt. However, both his ethnic and religious identity prevented him from feeling protected and finding refuge in Egypt.

“When I was in Church, someone came and beat me.”

Hoping to find a better situation, he crossed the Sinai into Israel. Without any support or connections in Tel Aviv, Berhe slept for over a month in Levinsky Park. With the little money he had saved over his first month, he moved into a one-room apartment with a friend.

“They think we are not educated. We are just as educated as anybody else.”

Today, after seven years in Israel, he reflects on his life here:

“Life, you know, from time to time is very bad. At first, the people of Israel, they helped us. But after, life started changing because of politics. It’s not good for us. They treat us like we are not human beings. They think we are not educated. We are just as educated as anybody else.”

In an attempt to help change the situation for his fellow Eritreans, Berhe began volunteering at the Eritrean Community School in 2013. Located on the third floor of a building close to the Central Bus Station, the school features five classrooms and a computer room. It is run solely by volunteers and paid for by the community. The center’s main activities revolve around teaching Tigrinya – the Eritrean language – to the next generation and providing a safe place to go after school.

“Families are constantly working to get money for their children,” Berhe says, describing the situation for most Eritrean families living in Israel. “Because of that, there is nobody at home. For the child, this is not good. But if the child comes here [to the community school], then the child has safety.”

There is little support for Eritrean children living in Israel, whether they were born in Israel or in Eritrea. But the Eritrean Community School provides a safe place for young children and helps students feel connected to Eritrea, a country to which they may one day return under safe conditions.

“[It is important to] learn the mother tongue because, children born here, they speak only Hebrew. But the family came from our country. There is this argument between the child and the family because of the language,” Berhe says.

Berhe hopes that through the Tigrinya lessons, the children will learn to respect the culture from which they come, as well as understand the sacrifices their parents made – and continue to make – in order to provide for them.

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter