Congolese boy recovers childhood, step by step

Congolese boy recovers childhood, step by step

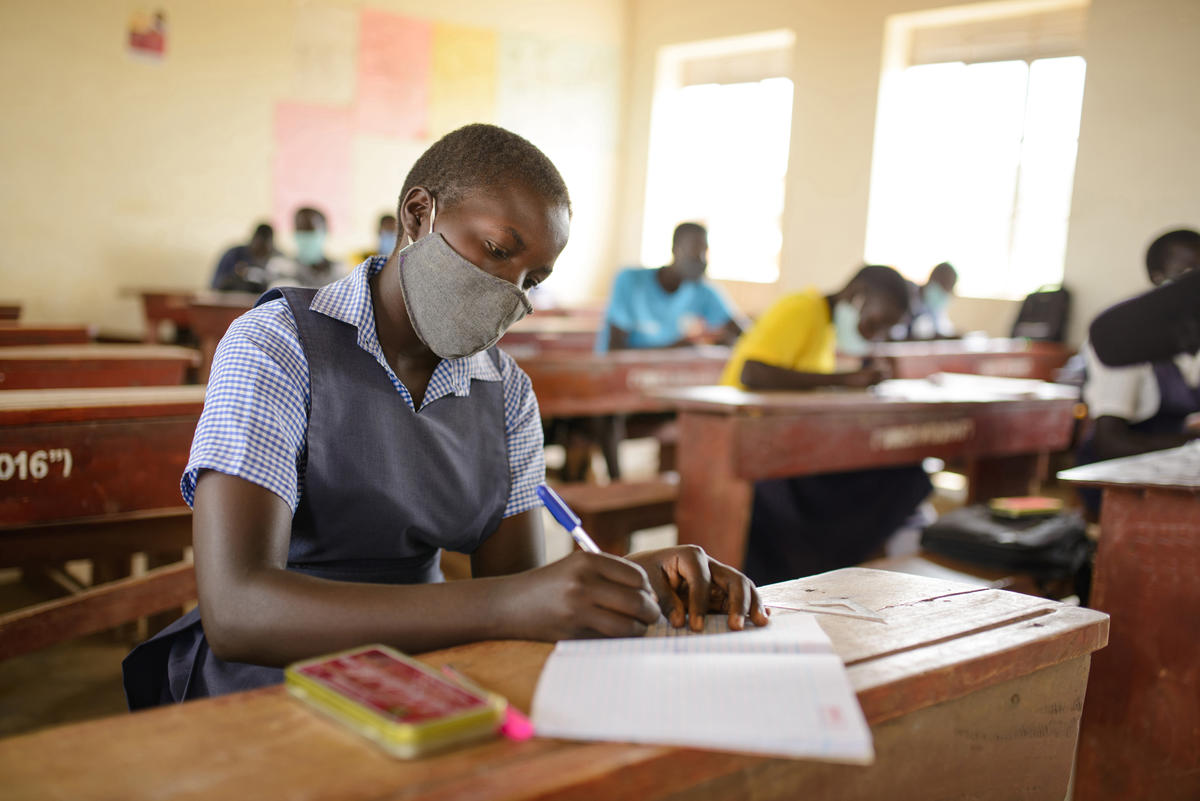

BETOU, Republic of the Congo, May 6 (UNHCR) - It is 10:30 in the morning, recess time for the hundreds of children who attend the 15 Avril refugee camp school in Bétou in north-eastern Republic of the Congo. Kids of all ages are running in the dirt in a sea of laughter and cries. In the middle of this boisterous crowd, a little boy is chasing a teenager about twice his size. He can't catch him, and finally decides to throw a rock at his schoolmate's back.

Despite the bravado, the stone-thrower, Albert, is only nine years old. "He is a child who doesn't deal well with vexation," explains his second grade teacher, Dénago Samuel. "But he is a brilliant student whose results are above average."

These are encouraging results for a boy who, until a year ago, did not attend school because he was too violent. "He used to fight a lot with others, he was withdrawn, could hardly speak and was tied to his mother's apron strings," recalls Maguelone Arsac, UNHCR's protection officer in Bétou.

Albert was in a bad state last year, when he arrived in Bétou after spending two long months being forced to serve as a porter for the enemy in his native Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). He remembers fearing for his life during this period of captivity.

The boy belongs to an ethnic group that was targeted by militia, igniting a violent ethnic conflict in Equateur province of north-western DRC at the end of 2009. He was separated from his family during an attack on his village. While 116,000 people fled the region, crossing the Oubangi River that divides the DRC and the Republic of the Congo, Albert remained in the combat zone and was taken by one of the militia groups.

"One woman told me to lie and say that I was from another ethnic group if anyone asked," he recalls nervously. Although he says that he was not mistreated, he lived in terror: "I would see them go in the morning. I would hear the gun shots and see the smoke. I knew they were looting and killing."

Two months later, as his captors were losing ground to army forces, Albert was able to escape and cross the Oubangi to safety. Once in the Republic of the Congo, UNHCR reunited him with his family in Bétou - 50 kilometres north of where he was found. But the joy of seeing his mother and eight siblings again was quickly replaced by a profound sorrow as he learnt his father had died in the fighting back home.

Today, Albert's situation remains precarious. Without the support of a father - though he is still in denial about the man's death - his whole family is now in a state of extreme vulnerability. His mother went back to the DRC a few months ago and he lives with an aunt and his siblings at the 15 Avril refugee camp. The boy often only eats one meal a day despite the food rations his family receives.

Life is harsh, but there is hope for him. UNHCR provides Albert with school supplies to support him in his studies, and arranged for a psychological counsellor to help him cope with the trauma he went through. "We can feel he is a child who is socializing again. He is going to school and playing with others," says UNHCR's Arsac.

Nonetheless, Albert says deep down inside, he will always keep the memory of what he calls "a bad tale of many people being killed."

When asked about his future, he says he first wants to learn to read and write well. After that, he wants to become a nurse: "Because when people are sick and suffering, you give them medication or an injection, and they heal."

On March 12, the warring groups in the DRC's Equateur province signed a peace agreement after a year-long community dialogue, sponsored in part by UNHCR. This reconciliation could eventually pave the way for refugees like Albert to return home.

By Anouk Desgroseilliers

In Bétou, Republic of the Congo