Safeguards needed for EU asylum rules on "safe countries", warns UNHCR

Safeguards needed for EU asylum rules on "safe countries", warns UNHCR

GENEVA, Oct 1 (UNHCR) - On the eve of a European Union meeting to discuss EU asylum legislation on "safe countries", the UN refugee agency has expressed concerns that if these concepts are introduced without proper safeguards, they could seriously compromise the protection of refugees.

The EU Justice and Home Affairs Council is set to meet on Thursday and Friday in Brussels to discuss a crucial piece of EU asylum legislation that may permit the establishment of lists of countries that are considered "safe".

According to UNHCR, the asylum procedures directive - one of two remaining pieces of legislation to be decided during the first phase of EU harmonization of asylum law and practices - is of fundamental importance to the whole future of the asylum system in Europe.

On the agenda of this week's meeting are two separate notions concerning "safe countries". Firstly, the idea that an asylum seeker can be returned to another country where he or she could have claimed asylum - the so-called "safe third country" concept. Secondly, the idea that some asylum seekers' countries of origin are safe, and they can therefore be presumed not to be refugees.

Among a number of problems it has with the current draft directive, UNHCR said it was concerned that if "safe country" concepts were introduced without sufficient safeguards, they could seriously compromise the protection of refugees and deviate from international standards.

The refugee agency is particularly worried that the asylum procedures directive may allow lists of "safe third countries" to be established and that, due to insufficient safeguards or vague terminology, these could lead to asylum seekers being summarily sent back to non-EU countries without any guarantee that their asylum claim will be properly dealt with there. Such countries might be transit countries, with which the asylum seeker has no firm connection whatsoever, or even a country where the asylum seeker has never set foot.

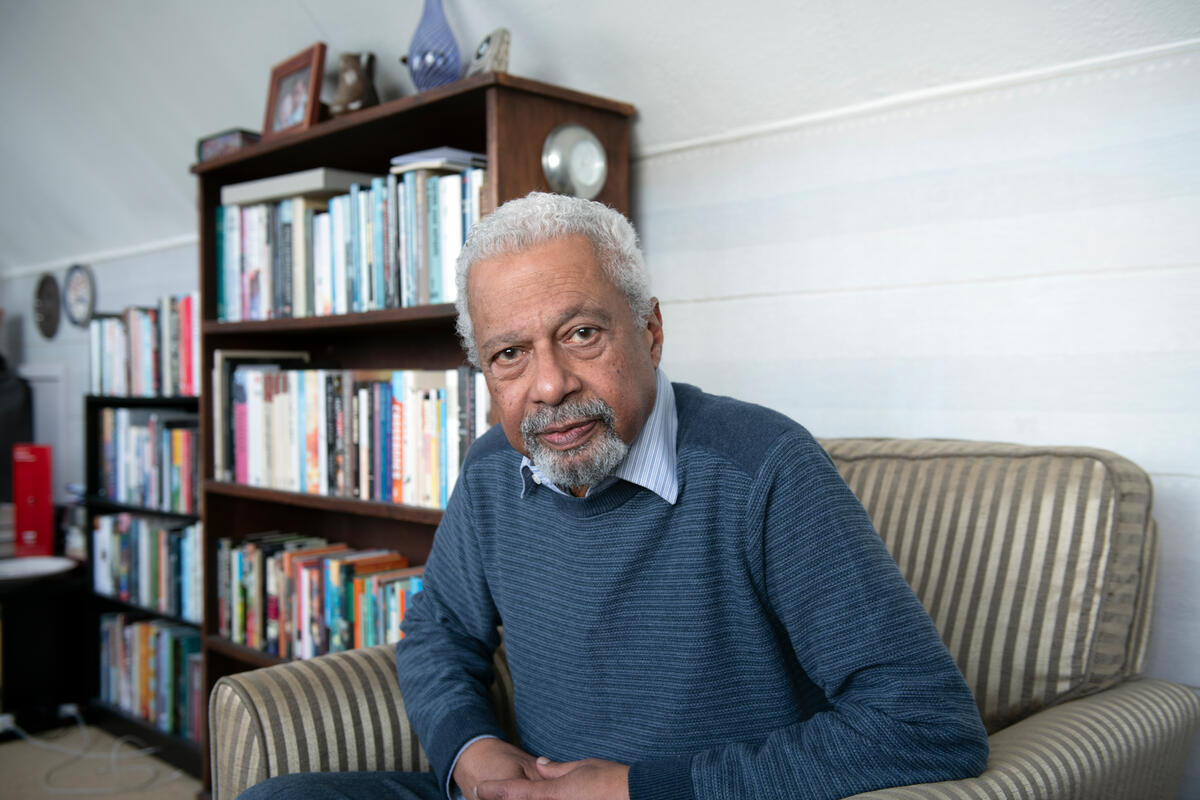

"If this were to happen, it would be a clear case of avoiding responsibilities," said Raymond Hall, Director of UNHCR's Europe Bureau. "Even worse, if it is done without the express agreement of the third country, it could lead to people being stuck in airports, unable to access any asylum system anywhere, or even to people being returned to a dangerous situation in their home country - which is, of course, against international law."

UNHCR has released a series of comments on the draft legal texts currently under negotiation, telling the EU member states that a number of conditions need to be met before responsibility for an asylum seeker can be transferred from one country to another.

Firstly, the decision should not be unilateral. The so-called safe third country should be notified that the asylum seeker is being transferred and give "its express consent to accept responsibility for examining the application."

The country itself should be safe not only in theory, i.e. because it has signed the 1951 Refugee Convention and has a national asylum system. The asylum system should be fully functioning in practice, which is often not the case. For example, access to an asylum procedure can often be a major problem. UNHCR has told EU states that, in the absence of a common set of legally binding standards such as those contained in the EU's own Dublin Regulation, the judgement on whether a third country is safe can only be reached through an individual analysis of each case and not on the basis of lists.

Historically, the "safe third country" notion has been mostly used by EU countries as a tool for dealing with applicants coming via Central European countries such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia, which share a border with the EU. UNHCR said it believes this concept will largely lose its relevance when these states themselves join the EU next year.

With regard to the return of people to transit countries, UNHCR suggested there should be "a meaningful link or connection that would make it reasonable for an applicant to seek asylum in that State.... Mere transit through a third country does generally not constitute such a meaningful link." The agency also expressed concern at proposals to expand the application of the "safe third country" concept to include countries with which the applicant does not necessarily have any links at all, and has not even travelled through.

On the issue of "safe countries of origin," UNHCR said it does not oppose the concept if it is used as a tool to decide which asylum seekers are subjected to accelerated procedures, particularly at the appeal stage. However, the procedures themselves should have sufficient safeguards, including some form of review. An asylum seeker must be given an opportunity to explain why he or she might be at risk in a country that is generally considered to be safe.

In addition, the procedure to determine which countries of origin are "safe" should be sufficiently flexible to take account of both sudden and gradual changes in a given country of origin.

"If a country experiences a coup d'état or some other form of social or political upheaval," said Hall, "it is obviously important that immigration officials do not continue automatically to treat it as a 'safe' country, because it still appears on their safe country list. The system will need to take account of increased risks of persecution without delay, otherwise terrible mistakes could be made."