New report:

UNHCR Global Trends 2021

Released 17 June 2022

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO (DRC). Binianga Asiya and her family are Congolese returnees living in their new house in Tshikapa in the Kasai region of south-central Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). She fled to Angola with her husband, Moualimu Moussa Mulumba (right), and their three children during the violence that began in 2017 but has returned to start over. © UNHCR/John Wessels

GLOBAL TRENDS

FORCED

DISPLACEMENT

IN 2019

We are witnessing a changed reality in that forced displacement nowadays is not only vastly more widespread but is simply no longer a short-term and temporary phenomenon.

Global Trends is published every year to analyze the changes in UNHCR’s populations of concern and deepen public understanding of ongoing crises. UNHCR counts and tracks the numbers of refugees, internally displaced people, people who have returned to their countries or areas of origin, asylum-seekers, stateless people and other populations of concern to UNHCR. These data are kept up to date and analyzed in terms of various criteria, such as where people are, their age and whether they are male or female. This process is extremely important in order to meet the needs of refugees and other populations of concern across the world and the data help organizations and States to plan their humanitarian response.

2019 IN REVIEW

TRENDS AT A GLANCE

79.5 MILLION

FORCIBLY DISPLACED WORLDWIDE

at the end of 2019 as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing public order.

- 26.0 million refugees

- 20.4 million refugees under UNHCR’s mandate

- 5.6 million Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate

- 45.7 million internally displaced people1

- 4.2 million asylum-seekers

- 3.6 million Venezuelans displaced abroad

1 Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre.

40% CHILDREN

An estimated 30 – 34 million of the 79.5 million forcibly displaced persons were children below

18 years of age.

2.0 MILLION

NEW CLAIMS

Asylum-seekers submitted 2.0 million new claims. The United States of America was the world’s largest recipient of new individual applications (301,000), followed by Peru (259,800), Germany (142,500), France (123,900) and Spain (118,300).

5.6 MILLION

DISPLACED PEOPLE RETURNED

5.6 million displaced people returned to their areas or countries of origin, including 5.3 million internally displaced persons and 317,200 refugees.

85%

HOSTED IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

Developing countries hosted 85 per cent of the world’s refugees and Venezuelans displaced abroad.

The Least Developed Countries provided asylum to 27 per cent of the total.

73%

HOSTED IN NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES

73 per cent of refugees and Venezuelans displaced abroad lived in countries neighbouring their countries of origin.

107,800

REFUGEES RESETTLED

UNHCR submitted 81,600 refugees to States for resettlement. According to government statistics, 26 countries admitted 107,800 refugees for resettlement during the year, with or without UNHCR’s assistance.

68%

ORIGINATED FROM JUST FIVE COUNTRIES

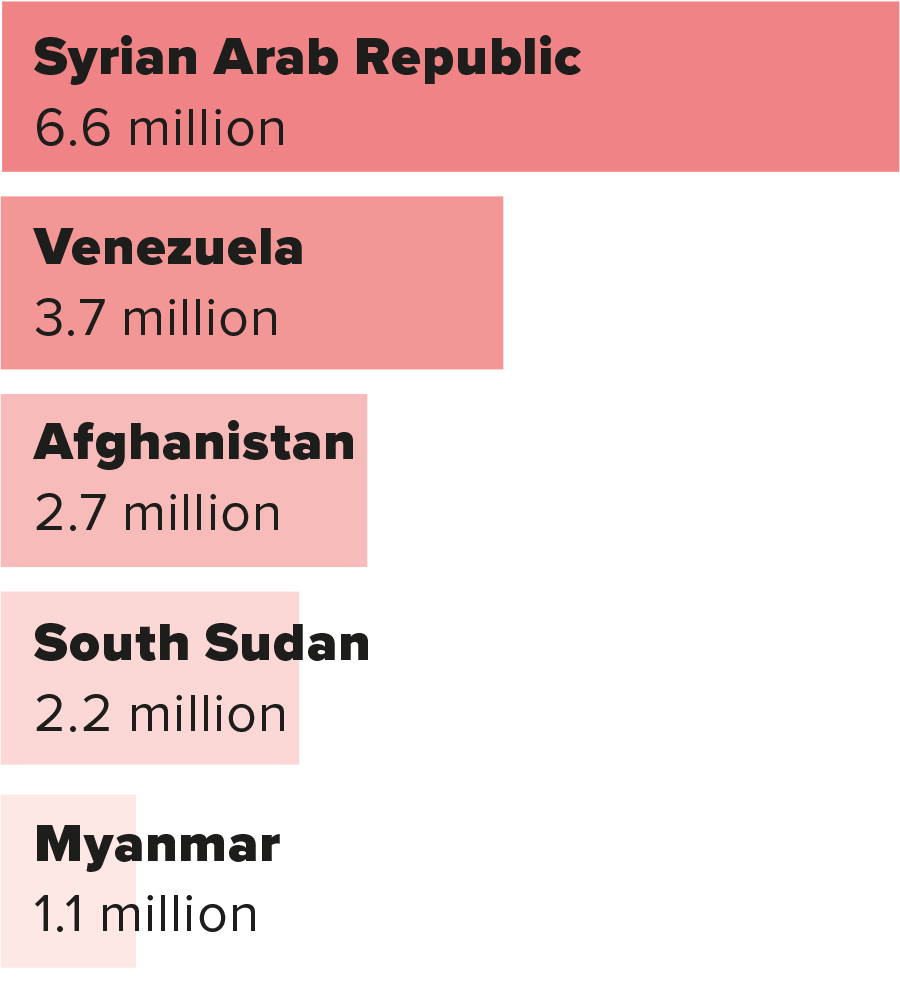

More than two thirds (68 per cent) of all refugees and Venezuelans displaced abroad came from just five countries.

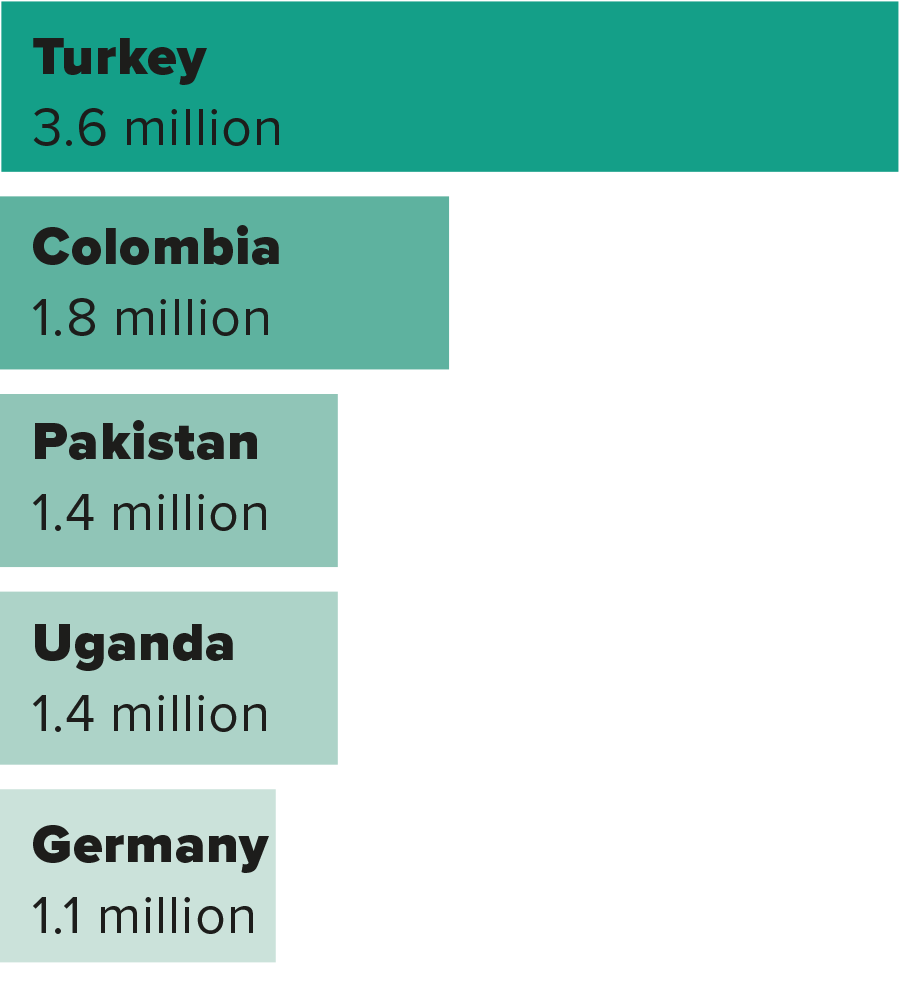

3.6 MILLION

REFUGEES HOSTED IN TURKEY

Turkey hosted the largest number of refugees worldwide, with 3.6 million people. Colombia was second with 1.8 million, including Venezuelans displaced abroad.

1 IN 6

ARE DISPLACED

Relative to their national populations, the island of Aruba hosted the largest number of Venezuelans displaced abroad (1 in 6) while Lebanon2 hosted the largest number of refugees (1 in 7)

2 In addition, Lebanon hosted 476,000 and Jordan 2.3 million Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate.

4.5 MILLION

DISPLACED VENEZUELANS

93,300 refugees, 794,500 asylum-seekers and 3.6 million Venezuelans displaced abroad.

Global forced displacement

Almost 80 million people are forcibly displaced

BURKINA FASO. Malian refugees in Goudoubo camp on their way to receive new dignity kits at a distribution point in the camp. With no prospects for return as the conflict continues at home, these refugees are now exposed to rising insecurity in their new host country. Following attacks and ultimatums by armed groups, the Goudoubo refugee camp, recently home to 9,000 refugees, is now effectively empty as they have fled to seek safety elsewhere. © UNHCR/SYLVAIN CHERKAOUI

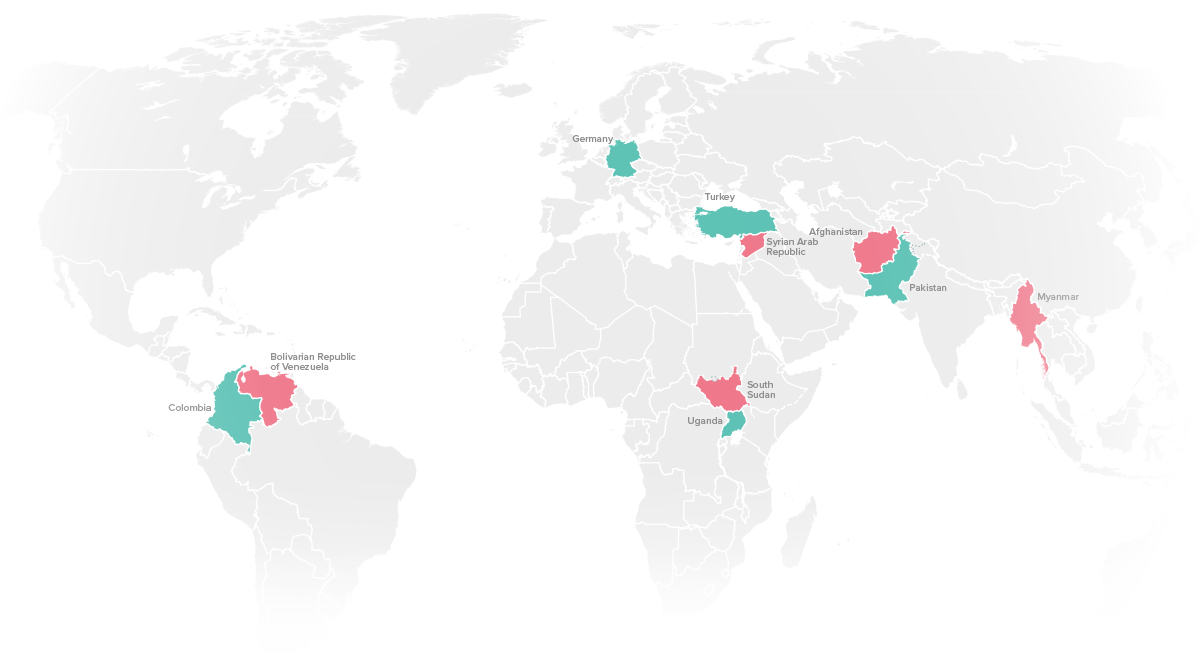

At least 100 million people were forced to flee their homes during the last 10 years, seeking refuge either within or outside the borders of their country. Forced displacement and statelessness remained high on the international agenda in recent years and continued to generate dramatic headlines in every part of the world.

As we approach two important anniversary years in 2021, the 70th anniversary of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 60th anniversary of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, it is clear these legal instruments have never been more relevant.

Several major crises contributed to the massive displacement over the past decade, and the numbers include people who were displaced multiple times. These crises included but are not limited to the ones listed here:

- the outbreak of the Syrian conflict early in the decade, which continues today

- South Sudan’s displacement crisis, which followed its independence

- the conflict in Ukraine

- the arrival of refugees and migrants in Europe by sea

- the massive flow of stateless refugees from Myanmar to Bangladesh

- the outflow of Venezuelans across Latin America and the Caribbean

- the crisis in Africa’s Sahel region, where conflict and climate change are endangering many communities

- renewed conflict and security concerns in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Somalia

- conflict in the Central African Republic

- internal displacement in Ethiopia

- renewed outbreaks of fighting and violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- the large humanitarian and displacement crisis in Yemen.

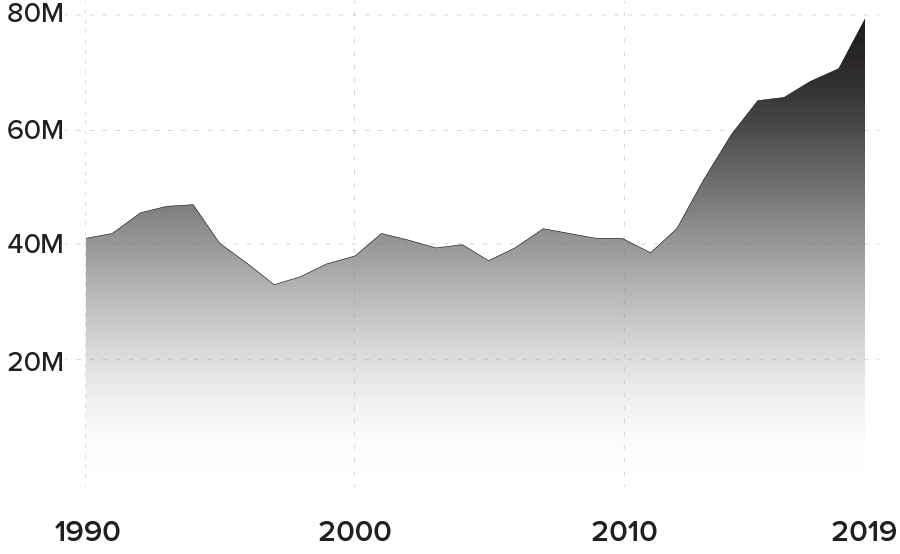

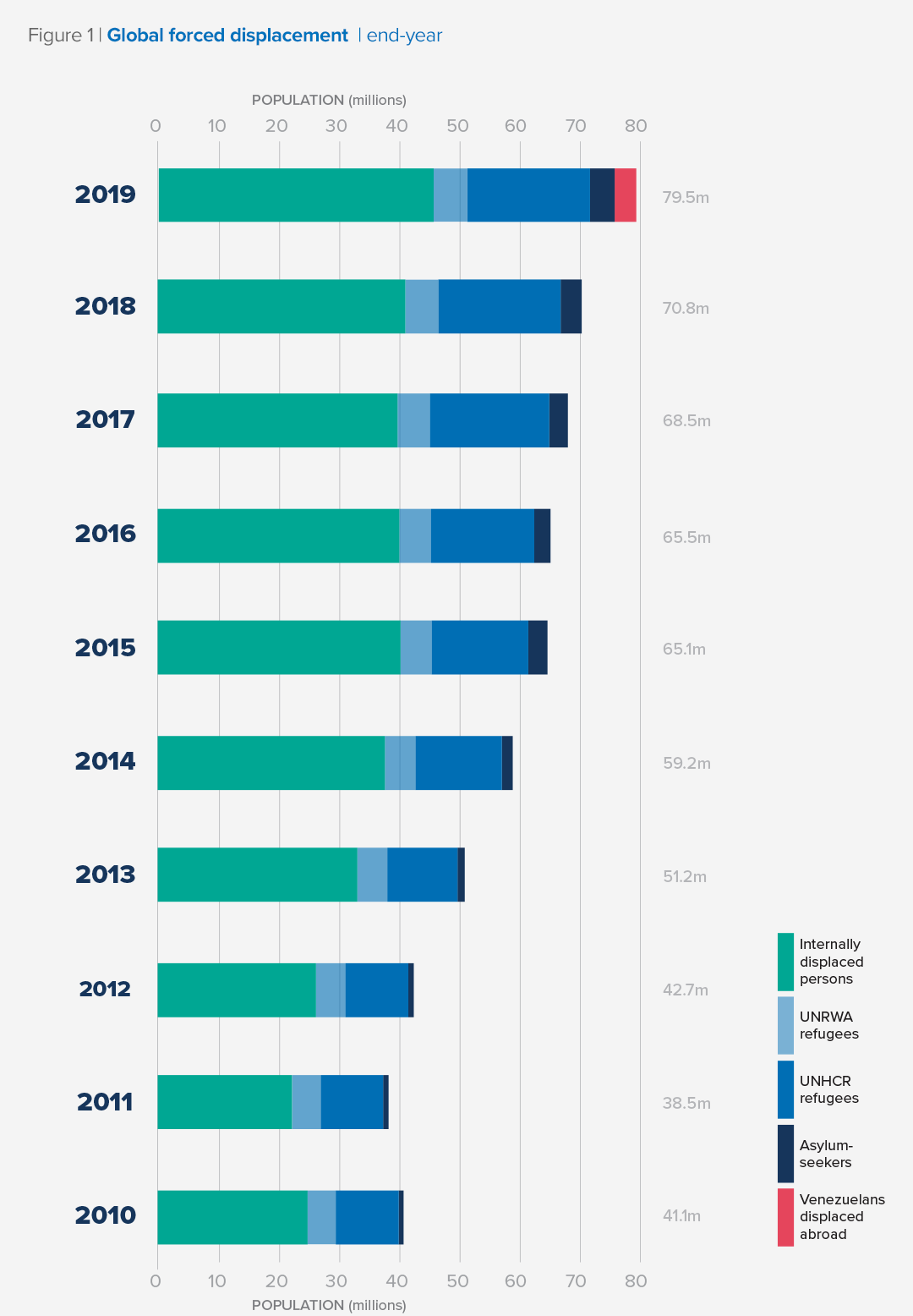

Tens of millions of people were able to return to their places of residence or find other solutions, such as voluntary repatriation or resettlement to third countries, but many more were not and joined the numbers of displaced from previous decades. By the end of 2019, the number of people forcibly displaced due to war, conflict, persecution, human rights violations and events seriously disturbing public order had grown to 79.5 million, the highest number on record according to available data.3 The number of displaced people was nearly double the 2010 number of 41 million (see Figure 1) and an increase from the 2018 number of 70.8 million. The most recent annual increase is due to both new displacement and the inclusion in this year’s report of 3.6 million Venezuelans displaced abroad who face protection risks, irrespective of their status – a category that was not included in the broader global forced displacement total in previous versions of the Global Trends report.

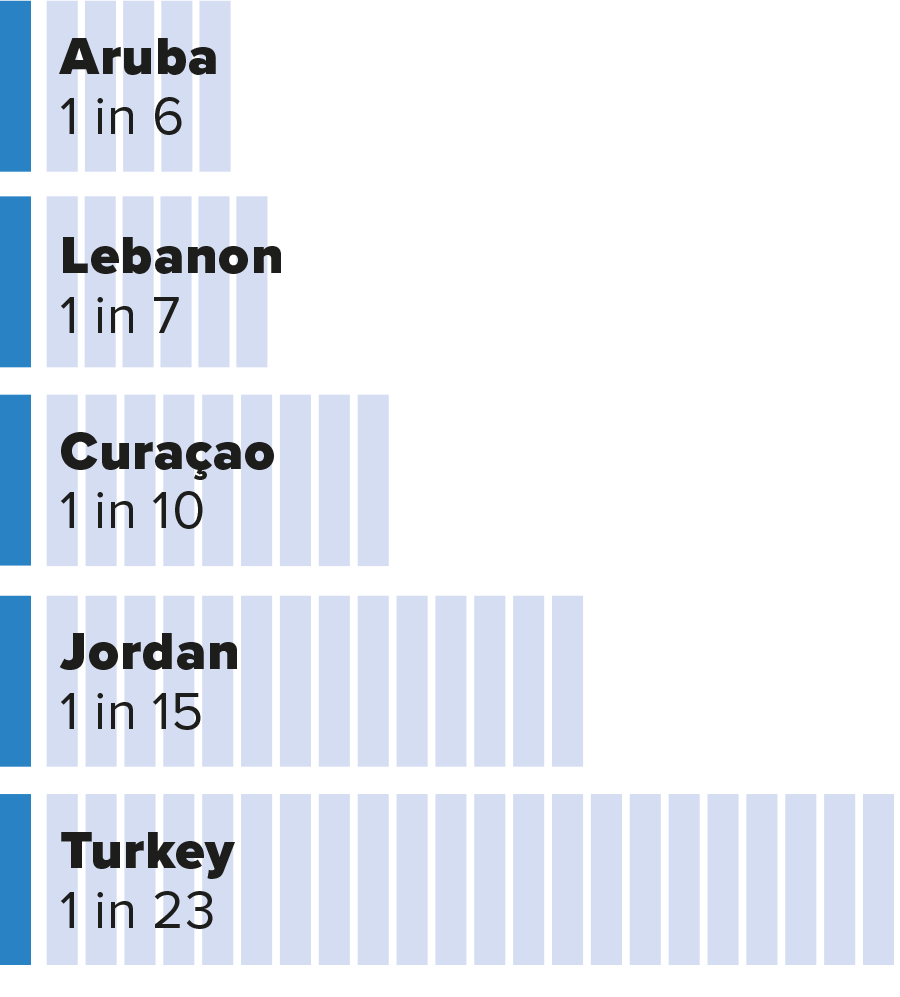

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Burkina Faso, the Syrian Arab Republic (Syria), the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (Venezuela) and Yemen represent just a few of the many hotspots in 2019 driving people to seek refuge and safety within their country or flee abroad to seek protection.

The proportion of the world’s population who were displaced continued to rise. One per cent of the world’s population – or 1 in 97 people – is now forcibly displaced. This compares with 1:159 in 2010 and 1:174 in 2005 as the increase in the world’s forcibly displaced population continued to outpace global population growth.5

During 2019, an estimated 11.0 million people were newly displaced. While 2.4 million sought protection outside their country,6 8.6 million were newly displaced within the borders of their countries.7 Many displaced populations failed to find long-lasting solutions for rebuilding their lives. Only 317,200 refugees were able to return to their country of origin, and only 107,800 were resettled to third countries. Some 5.3 million internally displaced people returned to their place of residence during the year, including 2.1 million in the Democratic Republic of the Congo8 and 1.3 million in Ethiopia. In many cases, however, refugees and IDPs returned under adverse circumstances in which the sustainability of returns could not be assured.

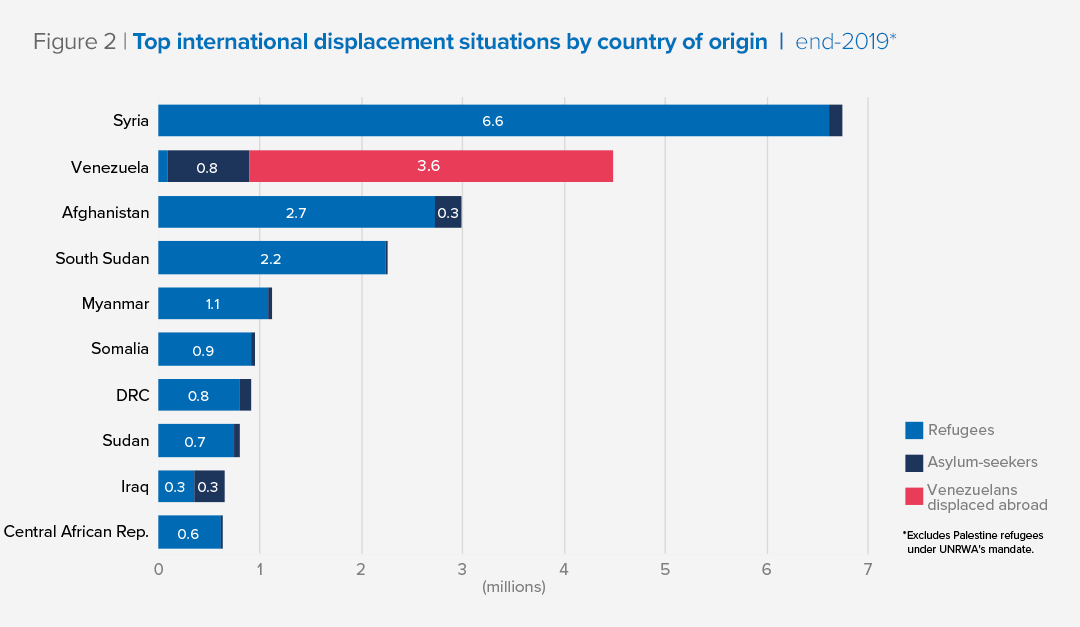

At the end of 2019, Syrians continued to be by far the largest forcibly displaced population worldwide (13.2 million, including 6.6 million refugees and more than six million internally displaced people). When considering only international displacement situations, Syrians also topped the list with 6.7 million persons, followed by Venezuelans with 4.5 million. Afghanistan and South Sudan had 3.0 and 2.2 million, respectively (see Figure 2).9

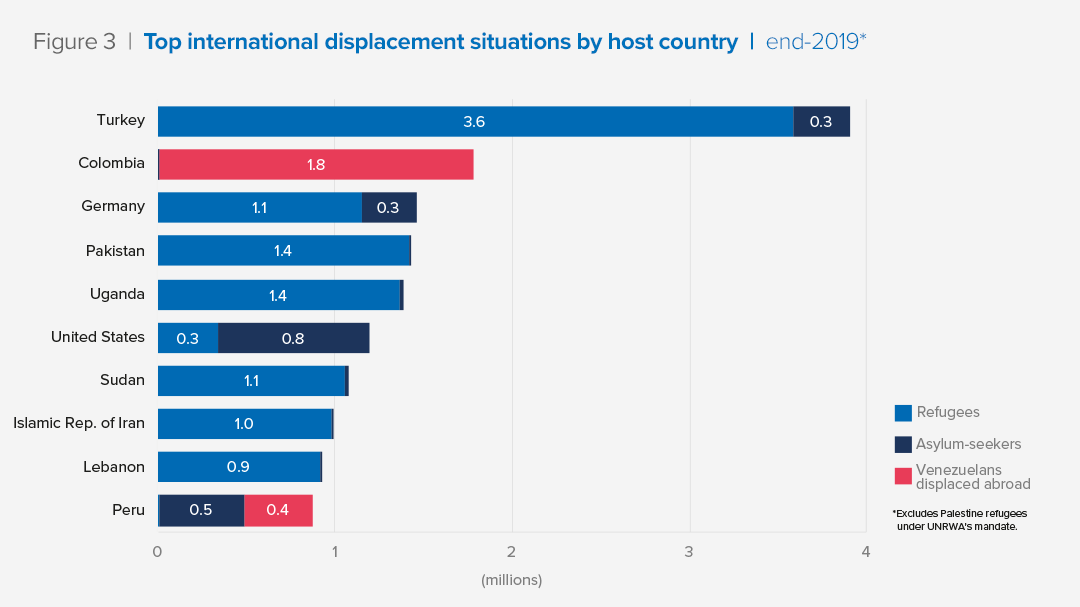

Turkey hosted the highest number of people displaced across borders, 3.9 million, most of whom were Syrian refugees (92%). Colombia followed, hosting nearly 1.8 million displaced Venezuelans. Germany hosted the third largest number, almost 1.5 million, with Syrian refugees and asylum-seekers constituting the largest groups (42%). Pakistan and Uganda hosted the 4th and 5th largest number, with about 1.4 million each (see Figure 3).

During crises and displacement, children, adolescents and youth are at risk of exploitation and abuse, especially when they are unaccompanied or separated from their families (these children are referred to as UASC). In 2019, UASC lodged around 25,000 new asylum applications. In addition, 153,300 unaccompanied and separated children were reported among the refugee population at the end of 2019. Both figures, however, are significant underestimates due to the limited number of countries reporting data.

Note:

The main focus of this report is the analysis of statistical trends and changes in global displacement from January to December 2019 among populations for whom UNHCR has been entrusted with a responsibility by the international community.10 The data presented are based on information received as of 15 May 2020 unless otherwise indicated.

The figures in this report are based on data reported by governments, non-governmental organizations and UNHCR. Numbers are rounded to the closest hundred or thousand. As some adjustments may appear later in the year in the Refugee Population Statistics online database,11 figures contained in this report should be considered as provisional and subject to change. Unless otherwise specified, the report does not refer to events occurring after 31 December 2019.

3. These included 26.0 million refugees: 20.4 million under UNHCR’s mandate and 5.6 million Palestine refugees registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). The global figure also included 45.7 million internally displaced persons (source: IDMC), 4.2 million individuals whose asylum applications had not yet been adjudicated by the end of the reporting period, and 3.6 million Venezuelans displaced abroad.

4. For details on the Venezuela situation, see below.

5. National population data are from United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “World population prospects: The 2019 revision”, New York, 2019. See: https://population.un.org/wpp/

6. Consisting of more than 2.0 million new individual asylum claims and 382,200 refugees recognized on a prima facie or group basis. Some of these people may have arrived prior to 2019.

7. Based on a global estimate from IDMC.

8. This figure was released by the “Commissions de mouvements de population”, an inter-organizational mechanism which is held by provincial authorities and humanitarian actors. It covers the period from April 2018 to September 2019.

9. Excluding Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate.

10. See Chapter 7 for a definition of each population group.

11. http://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics

Peru. “I arrived today at the border with my husband and two children,” says Daniela, 29, with her 10-month-old baby at the Ecuador-Peru border. “We left Venezuela five days ago by bus. We want to go to Lima where we can stay with friends. It is impossible to remain in Venezuela, there is no medicine, [and] little food.” © UNHCR/Hélène Caux

Venezuela Situation

By the end of 2019, some 4.5 million Venezuelans had left their country, travelling mainly to other parts of Latin America and the Caribbean. It is the largest exodus in the region’s recent history and one of the biggest displacement crises in the world. More than 900,000 Venezuelans have sought asylum in the last three years, including 430,000 in 2019 alone. Some countries in the region, such as Brazil, have taken steps to apply the extended refugee definition under the 1984 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees and national legislation, while other countries have gradually scaled up their capacity to process asylum claims and are developing simplified or accelerated refugee status determination case processing modalities. In addition, Latin American countries granted over 2.4 million residence permits and other forms of legal stay to Venezuelans by the end of 2019, which allow them to access some basic services. New visa requirements in many States along the Andean Corridor have left those on the move facing increased protection risks. Furthermore, the number of Venezuelans in an irregular situation continues to increase. At the end of 2019, over 50 per cent of Venezuelan refugees and migrants in Colombia were in an irregular situation. Based on reports received by UNHCR and its partners, as well as reliable information in the public domain from a wide range of sources about the situation in Venezuela, protection-sensitive arrangements are required, in particular protection against forced returns and access to basic services, and are thus promoted for all Venezuelans displaced abroad – irrespective of their status – to reinforce the protection dimension and consistent responses across the region.12

With the objective of ensuring an accountable, coherent, coordinated and protection-sensitive operational response for refugees and migrants from Venezuela across the region, UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) lead the Regional Inter-Agency Coordination Platform (R4V).13 In 2019, through its Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan (RMRP), partners’ activities benefited over 1.6 million people in 16 countries. For the 2020 Response Plan,14 151 partners throughout the region aim to support 4.1 million people, including vulnerable host community members, including through targeted COVID-19 response activities. The Regional Inter-Agency Coordination Platform is complemented by eight UNHCR and IOM co-led national and sub-regional platforms in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru (at national levels) and in the Caribbean, Central America, Mexico and Southern Cone (at sub-regional levels).

12. UNHCR, Guidance Note on International Protection Considerations for Venezuelans – Update I, May 2019,

https://www.refworld.org/docid/5cd1950f4.html

Can we predict forced displacement for the next 10 years?

It is very difficult to predict global forced displacement, or its impact on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Such predictions typically rely on historical population trends and anticipate future events, which is sometimes impossible. Based on the displacement trajectory in the 1990s and 2000s, few people could have foreseen the rapidly growing number of displaced people we have seen over the last decade.

From the mid-1990s until around 2010, the number of displaced people remained relatively stable because even though new displacement continued, at the same time many displaced people eventually repatriated, built permanent homes in their host communities or resettled in third countries. In the aftermath of the early Balkan wars and the Rwandan genocide, for example, global displacement figures remained well below 40 million, and as low as 34 million in 1997, according to estimates. Between 2000 and 2009, the numbers of displaced generally ranged between 37 and 42 million.

A sign of solidarity

On 10 September 2019, the Government of Rwanda signed an agreement with the African Union (AU) and UNHCR to provide urgent and lifesaving assistance to African refugees and asylum-seekers currently being held in detention centers in Libya. This agreement followed a generous offer from Rwanda to host up to 30,000 vulnerable people at risk and stranded in Libya. Under the memorandum of understanding, UNHCR in partnership with the Government of Rwanda and the AU has established an Emergency Transit Mechanism (ETM), to facilitate the relocation of up to 500 people of concern at any given time from the conflict zones in Libya to safety in Rwanda, while continuing to seek durable solutions options in and outside the country. The ETM in Rwanda complements the Emergency Evacuation Transit Mechanism established in Niger in 2017.

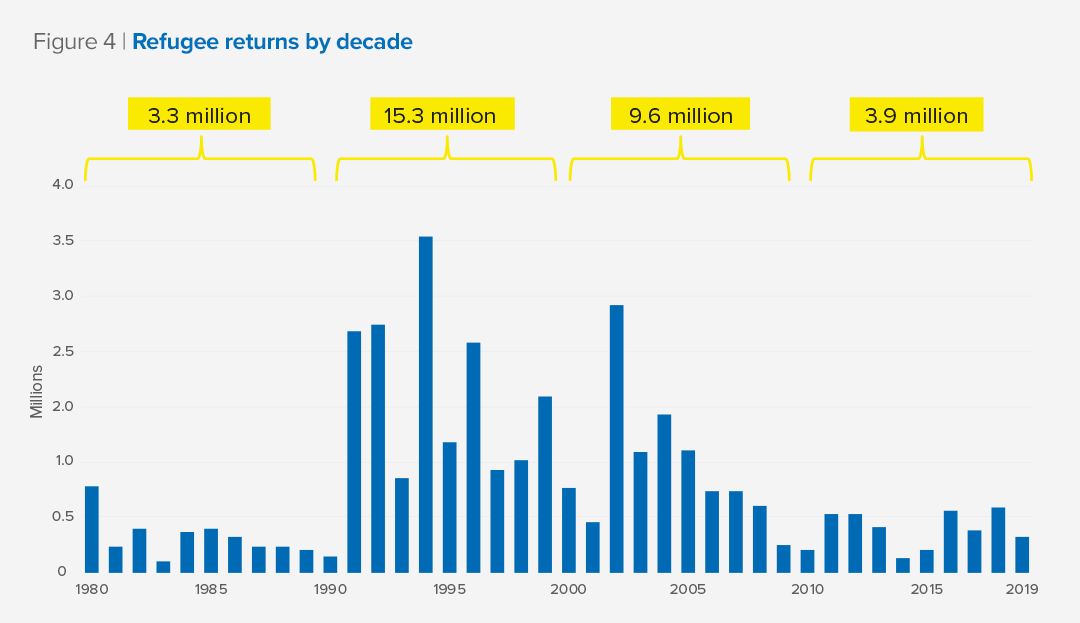

The last decade, however, brought a major shift. More people sought refuge, but those who had been displaced had fewer options for rebuilding their lives. As wars and conflicts dragged on, fewer refugees and internally displaced people were able to return home, countries accepted a limited number of refugees for resettlement and host countries struggled to integrate displaced populations. For instance, only 3.9 million refugees were able to return to their country of origin between 2010 and 2019. This compares to almost 10 million refugees who returned home during the previous decade and more than 15 million two decades prior (see Figure 4). With more people becoming displaced and fewer being able to return, an increasing number find themselves in protracted and long-lasting displacement situations. The world has clearly shifted from a decade of solutions to a decade of new and protracted displacement.

Climate change and natural disasters can exacerbate threats that force people to flee within their country or across international borders. The interplay between climate, conflict, hunger, poverty and persecution creates increasingly complex emergencies. For example, food insecurity may become a major driver of conflicts and displacement. An international alliance of the United Nations, governmental and non-governmental agencies working to address the root causes of extreme hunger reported that conflict, weather extremes and economic turbulence contributed to several disturbing trends. The group reported that at the end of 2019, 135 million people across 55 countries and territories experienced acute food insecurity.15 In addition, 75 million children had stunted growth and 17 million suffered from wasting. These findings represented the highest level of acute food insecurity and malnutrition documented since the group’s first report in 2017. Eighty per cent of the world’s displaced populations were residing in these 55 countries or territories.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates how unexpected events can affect forced displacement predictions. Although the novel coronavirus had just emerged in late 2019, the subsequent pandemic has had, and at the time of this writing continues to have, an unprecedented global social and economic impact, also affecting asylum systems. For instance, the number of asylum applications registered in the European Union in March 2020 dropped by 43 per cent compared to February as asylum systems slowed or came to a halt with countries closing borders or implementing strict border restrictions in response to COVID-19.16 In other parts of the world, refugee registration, an essential protection activity at the core of refugee statistics,17 also dropped significantly despite efforts by some countries to resort to remote registration and documentation. As a result, global refugee and asylum statistics may under-represent the true magnitude of the number of people seeking international protection during the pandemic. This could increase the uncertainty for predicting global forced displacement in the future.

Whatever the predictions are for future global displacement, we must reverse the current trend and massively expand pathways for the forcibly displaced to rebuild their lives – whether in their home countries, in third countries or in their host communities. In 2019, UNHCR and its partners launched the Three-Year Strategy on Resettlement and Complementary Pathways.18 The strategy foresees resettlement of one million refugees and admission of two million refugees through complementary pathways such as family reunification or labour mobility schemes by 2028. For it to succeed, States need to offer more avenues to solutions for refugees in line with the objective of greater shared responsibility set out in the Global Compact on Refugees.

16. See https://easo.europa.eu/news-events/covid-19-asylum-applications-down-march

17. See Chapter 7 for more details on sources and basis of refugee statistics.

18. To work towards increasing the number of resettlement places and admissions, as well as expanding the number of countries offering these programmes, the Three-Year Strategy on Resettlement and Complementary Pathways was launched in 2019 by governments, non-governmental organizations, civil society and UNHCR. The strategy’s target of 60,000 resettlement departures to 29 States in 2019 has been achieved. In 2020, the goal is for 31 countries to resettle up to 70,000 refugees referred by UNHCR. See https://www.unhcr.org/protection/resettlement/5d15db254/three-year-strategy-resettlement-complementary-pathways.html

COLOMBIA. Venezuelans continue to make perilous journeys in search of refuge. “We did not have anything to eat back home. It was becoming too problematic, especially with the kids.” This family of 17 people has been walking for five days. They are trying to warm up in the sun after leaving their shelter early in the morning. © UNHCR/Hélène Caux

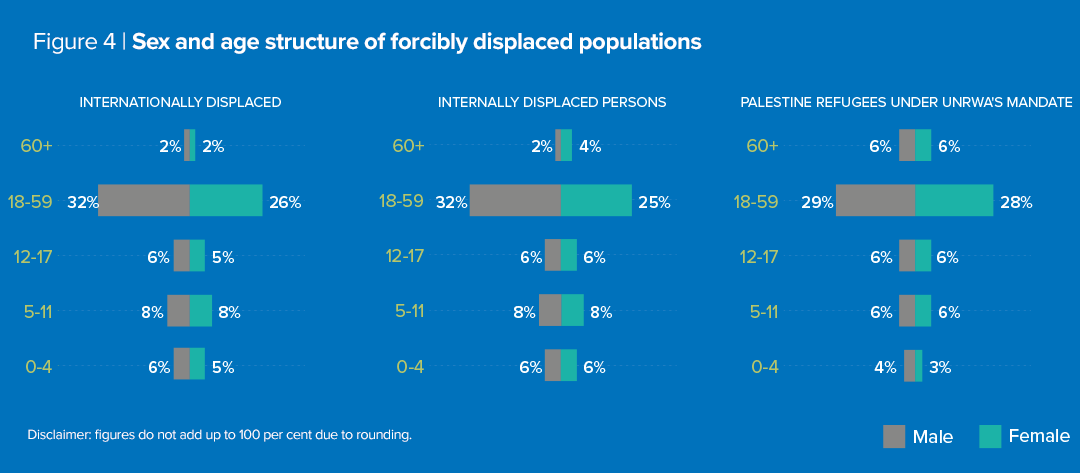

Demography of global forced displacement

Demographic data is crucial to understand the impact of displacement on different population groups. It is also essential to guide effective and efficient policy responses and programmatic interventions that address the needs of vulnerable groups. Sex- and age-disaggregated information is unfortunately not always available for all forcibly displaced populations. Statistical models or estimations can be used to fill these data gaps.

Based on a combination of different data sources (e.g. registration, surveys) and statistical models, UNHCR estimates that between 30 – 34 million of the 79.5 million forcibly displaced people are children (between 38 – 43 per cent). The three age pyramids present the demographic profile of the different populations.19

19. Demographic data is available for 80 per cent of refugees, 33 per cent of asylum-seekers and 1 per cent of Venezuelans displaced abroad. Within a 90 per cent posterior prediction interval, between 9.3 and 13.2 million (33 – 47%) of all refugees, asylum-seekers and Venezuelans displaced abroad combined are children under the age of 18. IDMC is the source of IDP data on children (www.internal-displacement.org). UNRWA is the source of data on Palestine refugee children (www.unrwa.org).