Syrian father Mahmoud Al-Bashawat, 39, and his wife Hayat Elwees, 38, are finally back together with their eight children (seven daughters and one son) in Vienna, after a long struggle to achieve their right to family reunification. Mahmoud left his family behind in a refugee camp in Jordan while he made the journey to Austria alone. Once he had been granted asylum, he could apply for the others to join him. But cost and other bureaucratic difficulties meant the family was separated for two-and-a-half years. © UNHCR/Stefanie J. Steindl Read the story

Executive summary

Family reunification is a way for refugees to reunite with family members. Under European Union (EU) law, refugees have the right to bring certain members of their immediate family to join them legally and safely, without having to resort to dangerous journeys. Many refugees leave behind spouses, children, parents, or other relatives when fleeing from conflict or persecution at home, for a variety of reasons such as the risks and hardship of the journey, or insufficient funds to enable all to escape. This can mean families stay apart for years.

Many refugees sought safety in Europe in 2015 and 2016. Since then, some European countries have allowed more families to reunite than others. This report looks at why many refugees in the 28 EU member states plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland, find it difficult to bring their loved ones to join them and the legal and practical obstacles they face. It also looks at what countries can do to help more refugee families.

While the EU’s Family Reunification Directive applies to 25 of the 28 EU member states (three states opted out), in practice the provisions are applied differently across Europe. Rather than facing unified procedures for family reunification, refugees have to navigate different requirements by different states, with some applying differing regulations for proving family relationships, and different degrees of flexibility over which family members are eligible for reunification. In addition, information to help navigate the procedure is available in very few countries. Many refugees and their families outside Europe may be eligible for reunification, but there are often too many obstacles preventing them from doing so.

One major obstacle concerns the rules allowing family members to join refugees in Europe. Generally, adults can apply for their husband or wife or under-age children to join them. Child refugees under 18 who came to Europe alone can apply for their parents to join them. Practices that apply to other family members differ across Europe. Unmarried partners, siblings, parents of adult refugees and grandparents usually cannot come, even if they are dependent on the person in Europe or the person in Europe is dependent on them. The same applies to others, such as orphaned nieces or nephews taken in by the family but not formally adopted.

UNHCR would like more European countries to be flexible and make sure more families can be together when they need each other. This would mean applying a broader definition under EU law of what a family means.

Secondly, EU law exempts refugees from having to meet additional hard-to-meet criteria regarding employment, accommodation and insurance if they apply within three months of being granted asylum. States have the option not to apply this time limit, but many do despite the difficulty refugees may experience in obtaining documentation such as birth certificates or travel documents in time, or getting to an embassy even when the European country may have none in the country where the family members live. UNHCR would like more countries to remove these time constraints.

A third obstacle for some is difficulty in getting to an embassy. For example, few European countries have functioning embassies in Syria, which means family members must get permission to enter a neighbouring country. Some European embassies in the countries where refugees’ families live do not process visa applications, which means family members must try to get a visa to apply elsewhere. When several trips to an embassy are required, this can be difficult. UNHCR would like more countries to allow the refugee family member in Europe to apply on his or her family’s behalf without the need for them to visit an embassy.

A fourth obstacle occurs when refugees do not have all the documents they need. Passports, or birth, death and marriage certificates might be missing or difficult to get access to. Some European countries accept other ways for refugees to prove their identity. UNHCR would like more countries to recognize that refugees may sometimes lack certain documents proving family links and not to let this be a barrier to reunification. In cases where family members have no travel documents, UNHCR wants more European countries to issue temporary documents or accept UN Convention travel documents or International Committee of the Red Cross travel documents.

To overcome difficulties arising from confusing requirements or procedures, UNHCR wants more countries to provide detailed guidance for new arrivals on what they need to do to apply for their families to join them, including any time constraints. Family reunification can be expensive because of travel costs, visa fees, the costs of DNA tests (where required) and other expenses and this can prevent families being able to reunite. To overcome this, UNHCR would like the EU to establish a fund to make family reunification easier for those who are unable to cover the fees.

Lastly, in Europe, people fleeing conflict and persecution may be given different forms of international protection. Some are given refugee status in accordance with the 1951 Refugee Convention and others are given subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection. Recently, some countries in Europe have been giving more people subsidiary protection, particularly Syrians. All refugees with full status can apply for some family members to join them. In some countries, those with subsidiary protection have more limited rights to reunification, or none at all, despite also being unable to return home. UNHCR wants all countries in the region to give people with subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection the same rights to family reunification as refugees.

If family reunification is made more straightforward, fewer family members will resort to dangerous journeys and will rely instead on safe and legal routes to join their loved ones in Europe.

Time and Majd are 4 and 5 years old. They are from Syria and live in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. They and their mother joined their father through family reunification. Their father found life very hard without them and now is happy to see they are “very normal kids who love animals and playing games” and have a future away from bombs dropping from the sky. © UNHCR/Humans of Amsterdam

Introduction

Family reunification mechanisms for refugees enable separated families to reunite.[1] They provide a form of legal pathway, which allows those reuniting to travel in safety. In the context of irregular and dangerous journeys to Europe, greater use of family reunification channels would allow more people to travel legally, thus contributing to better management of movements and reducing reliance on smugglers, while at the same time providing pathways to protection and avoiding the need for dangerous journeys.

The number of family members of refugees and other international protection beneficiaries granted permits for family reunification purposes varies significantly across Europe. In some countries, fewer than 20 people over a two-year period from 2016 to 2017 were granted permission to join family members already in the country with international protection. In others, such as in Belgium, in the same period over 12,500 persons were granted permission to join family members with international protection.[2] In 2017 alone, France issued over 23,200 permits for family reunification with people with refugee status or subsidiary protection (compared to just under 2,400 in 2016).[3] Similarly, in 2017, Germany issued more than 54,000 visas for family members of individuals with international protection as well as over 32,000 visas in 2018. There are positive experiences from across Europe in terms of some States being able to successfully process larger numbers of applications enabling more families to reunite as well as adopting flexible approaches to overcome some of the hurdles outlined in this report that many experience.

This report addresses family reunification in the European Union (EU)+ region (i.e. in the 28 EU Member States, along with Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland). The EU’s Family Reunification Directive[4] applies and has been transposed into national legislation in 25 of the EU Member States, while the remaining three,[5] along with Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland have national legislation that provides for reunification. While under EU law people granted refugee status[6] in Europe are legally entitled to bring some close members of their families to join them, with States also having the discretion to authorise the reunification of other family members, in practice many obstacles prevent refugees from being able to realise this right. Those granted subsidiary protection[7] or other complementary forms of protection[8] rather than refugee status face additional difficulties in some States. This is largely because beneficiaries of these types of protection status are not included within the personal scope of the Family Reunification Directive, although Member States enjoy the discretion to also apply its provisions to them.

Generally, barriers to the enjoyment of the right to family reunification facing international protection beneficiaries include:

- The application of a narrow definition of family in the context of family reunification by some States;

- Limited time frames in which refugees in some countries need to apply or else they have to fulfil additional requirements;

- Difficulties for family members outside Europe accessing embassies, including due to lack of embassy presence or conflict in some countries, in order to complete their applications or receive their visas;

- Lack of information and assistance in navigating complex reunification procedures;

- Lack of access to the documents required to prove family relationships, which is often the direct result of having had to flee in haste, as well as lack of access to travel documents;

- The high costs involved in the family reunification process; and

- The introduction of mandatory waiting periods by some States for persons granted subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection before they are able to apply for reunification.

Some of the barriers are the result of measures introduced following the increase in the number of refugees and migrants arriving to Europe in 2015 and 2016.

Some international protection beneficiaries, despite being eligible for family reunification, may encounter multiple barriers that in reality may make it impossible for them to access reunification. For example, in addition to navigating a complex application process, the country they wish to reunify in may not have an embassy in the country where some family members currently live; they may not have travel documents, their marriage certificate or the birth certificates of their children; and they may be simply unable to afford the costs associated with the process and the subsequent travel. As a result, families remain apart, sometimes for years, or else family members who were left behind must risk the dangerous irregular journey to and through Europe in order to join those already there. The intention to reunify with family members including parents, children, or spouses is one driver of irregular movement to and within Europe.

Furthermore, family reunification is amongst the channels available to European States to provide legal admission pathways for people in need of international protection, in addition to resettlement, humanitarian admission, as well as private sponsorship schemes, education visas, etc. UNHCR has called for European States to increase safe and legal pathways for people seeking international protection to travel to Europe in order to avoid dangerous journeys by crossing borders irregularly.[9]

This report examines the difficulties faced by beneficiaries of international protection in accessing family reunification in order to bring close family members to safely join them in Europe, focusing on the EU+ region. It identifies many of the obstacles they and their family members face in applying for family reunification, highlights some positive practice by European States, and makes recommendations for steps European States and the European Commission can take to make family reunification more accessible.

© UNHCR/Christos Tolis

Eritrean priest relies on faith to help handle the pain of separation in Greece

Difficulties to obtain documents and prove family links

There is a calm about Solomon Haile Mesein that belies the suffering and pain of separation that he has endured for the past seven years. He fled his native Eritrea in 2007, leaving behind his elderly parents, wife and three children (a girl, now almost 18 years old, and two boys aged 16 and 11). They were reunited in Kenya for three years before he had to move on again in 2010 – Father Solomon has only seen his family twice since then, visiting them in Uganda.

A recognized refugee now in Greece after arriving in 2010, he has been trying over the years to reunite the family but has met with failure so far. The authorities had twice rejected his family reunification application because he could not provide official family certificates. Obtaining new official documents from Eritrea would be impossible.

The right to family reunification

The right to family life and family unity under international and regional law applies to all, including refugees, but does not necessarily entail the right to family reunification in a chosen country.[10] However, in light of the particular situation of refugees and beneficiaries of subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection, who are unable to return to their country of origin, under EU law,[11] persons granted refugee status in an EU Member State have the right to bring members of their nuclear family to join them while Member States can also allow family members of those with subsidiary protection to join them. While third country nationals seeking to bring family members to the EU will normally have to meet several criteria, including a regular income or being independent of social welfare, have sufficient accommodation, health insurance and having good integration prospects, these requirements do not apply to refugees if the application for family reunification is submitted within three months from the date refugee status was granted.[12] However, in some States, refugees will have to meet these additional criteria if the application is submitted later than this. EU legislation on family reunification does not apply specifically to beneficiaries of subsidiary protection, but in practice a number of EU Member States provide the same favourable conditions as for refugees. Guidance on the Family Reunification Directive issued by the European Commission in 2014 supports such practices with the European Commission encouraging Member States “to adopt rules that grant similar rights to refugees and beneficiaries of temporary or subsidiary protection.”[13]

According to the Family Reunification Directive,[14] a person granted refugee status can apply for the following family members to join him or her:

- His or her spouse;

- His or her minor children or those of his or her spouse (where he or she or the spouse has custody, the children are dependent on him or her or the spouse, and the children are unmarried);

- His or her parents if the refugee is an unaccompanied child.

In addition, EU Member States may authorize the reunification of the following family members:

- The parents of the person granted refugee status where they are dependent;

- Unmarried children above the age of majority if they are unable to provide for themselves for health reasons;

- Unmarried partners; and

- Other family members if they are dependent on the refugee.

Under EU law, an adult refugee is allowed to bring his or her spouse as well as his or her children if they are under 18.

Unaccompanied refugee children are allowed to bring their parents.

EU States can also allow an adult refugee to bring:

-

His or her parents if they depend on the refugee;

-

His or her children above 18 if they are not married and are dependent;

-

His or her partner if they are not married; and

-

Other family members who depend on the refugee.

Seven-year-old sister Anmar and her cousin Abeer, 11, were finally reunited with Anmar’s brother in the northern German town of Lensahn. © UNHCR/Chris Melzer Read the story

Difficulties accessing family reunification

Despite many persons granted refugee status in the EU being legally entitled to bring their family members to join them and a number of States applying the same or similar conditions for people granted subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection, in practice many refugees are unable to access this right due to a variety of legal or practical obstacles in the application process as outlined below.

1. Limited definition of family

A major constraint is the limited definition of family applied by many EU Member States. While spouses and minor children are entitled to family reunification, the Family Reunification Directive allows for but does not compel EU Member States to authorize the reunification of others despite the relationships of dependency that may exist,[15] such as unmarried partners, parents of refugees over the age of 18, grandparents, and other relatives who may have become part of the nuclear family due to death or displacement. The European Commission has encouraged Member States to use the scope provided in the Directive that allows for reunification of other family members if they are dependent on the refugee “in the most humanitarian way, as [the relevant Article] does not lay down any restrictions as to the degree of relatedness of ‘other family members’.”[16] The Commission further encouraged Member States to regard dependency as the determining factor and also consider persons “not biologically related, but who are cared for within the family unit”, such as foster children. In practice, however, many EU Member States interpret the definition of family members more narrowly. Five EU Member States[17] restrict reunification to the family members which the Directive compels them to include within the scope of family reunification (i.e. spouses, minor children, and parents of unaccompanied children). In addition, in Liechtenstein and the United Kingdom, unaccompanied children do not have the right to family reunification and children do not have the right to family reunification in Switzerland with their parents or siblings abroad. Significant diversity exists in the national practices of the remaining Member States that also allow reunification with other family members, with some being more restrictive than others as illustrated below in the ‘Good practices’ section. Certain States also follow strict requirements for documenting family links which inhibits reunification for many, including those with customary marriages, unregistered long-term relationships, as well as in the case of non-biological family members and nieces and nephews, as addressed later in this report. For example, in April 2017, UNHCR highlighted the story of a Syrian father, Ahmad, whose family had taken in two minor nephews after their parents were killed. While Ahmad’s wife Sara and their three children were able to join Ahmad in Austria via regular family reunification channels, these were not applied to the two nephews as they had not been formally adopted.[18] UNHCR encourages EU Member States to “apply liberal criteria in identifying family members in order to promote the comprehensive reunification of families including with extended family members when dependency is shown between such family members.”[19] However, several EU Member States continue to apply the concept of dependency very narrowly. Furthermore, while scope is provided for the reunification of siblings through the provisions of the Family Reunification Directive addressing dependency, in practice only Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, Ireland,[20] Romania, Spain and Sweden provide for reunification between siblings in certain circumstances, usually on account of dependency. As a result, in most EU Member States orphaned unaccompanied children are prevented from being united with siblings even when this is in their best interest. In other cases, young adults who were the heads of their households in their country of origin are prevented from reuniting with brothers or sisters who were dependent on them. However, some EU Member States as listed above have taken a positive approach and enable reunification in such cases due to dependency or for medical reasons, an approach UNHCR welcomes and encourages other Member States to adopt. In addition, it is in practice very difficult for unaccompanied children to be reunited with persons other than their parents when the latter have passed away, despite provisions for this in the Directive. This is often due to strict requirements regarding proving previous custody or recognized legal guardianship. With full consideration of the risk of trafficking and the violation of custody rights, the right to reunite with family members in line with the Directive and national legislation (where the Directive does not apply) should be effectively pursued. Related to this, while unaccompanied children may be able to reunify with their parents in some countries,[21] no specific scope is provided for their reunification with older siblings above the age of 18 at the same time, even if the latter remain dependent on the parents. More flexibility with regards to the reunification of siblings would enable unaccompanied children to more effectively reunite with close family members who are in another non-European country. Under certain circumstances, provided it is in the best interest of the child, family reunification may also be possible in a third country, particularly when the child could reunite with parents in the third country.[22] Lastly, although the Directive allows EU Member States to limit reunification to family relationships formed prior to entry to the EU, in reality many refugees may have formed families after entry into the EU. At present, 13 States in the EU+ region restrict family reunification to families formed prior to entry into the EU or the country in which reunification is sought or prior to departure from the country of origin.[23]GOOD PRACTICES:

Several European States offer more flexibility in terms of which family members can benefit from family reunification, including Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain. For example, the Netherlands allows unmarried adult children who were part of the family at the time their parents fled the country to reunify, unless they now have family of their own or are financially independent. In Ireland, civil partnerships for same-sex couples are recognised as long as the civil partnership is in existence on the date the sponsor made an application for international protection.UNHCR recommendation:

European States should expand the scope of family reunification by consistently applying a broader definition of family, prioritizing dependency as the primary criterion, including for unaccompanied children seeking reunification with close family members.Unaccompanied children losing reunification rights when turning 18

In recent years, the length and barriers in the asylum process and the procedures to determine an application for family reunification have had a particularly negative impact on applications from unaccompanied children in certain States. Due to different interpretations of the Family Reunification Directive, certain EU Member States require that a child must be under 18 to be reunited with his or her parents not only when the application for international protection is made, but also at the time when a decision on the application for family reunification is taken by the authorities, resulting in cases where children have ‘aged out’ and thus become ineligible for family reunification. In response to this, in April 2018, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled in A and S v Staatssecretaris van Veiligheid en Justitie that unaccompanied children who reach the age of majority during the asylum process retain their right to family reunification. In the case in question, an Eritrean girl has had her reunification application for her parents rejected on account of the fact that her application was submitted after she had turned 18, as she had turned 18 during the eight months it had taken for her asylum application to be approved. The Court ruled that in cases where a child enters the territory of an EU Member State and applies for asylum while below the age of 18, he or she retains the right to family reunification provided that their application is made within a reasonable time. [24]

2. Limited time frames to apply

Another major obstacle many face is that several States provide limited time frames in which applications for family reunification have to be lodged or else face additional requirements that are hard to meet. The Family Reunification Directive provides EU Member States with discretion noting that they may require persons granted refugee status in the EU to apply for family reunification within three months from the time they are granted refugee status. While most States within the EU+ region do not make this a requirement and have no time limit for applications for family reunification, 15 countries[25] do apply a time limit, usually of three months from the time international protection is granted. If applications are not made within the set period as per these countries’ requirements, the additional self-sufficiency requirements may apply requiring the sponsor to show evidence of sufficient housing, income or resources to maintain the family, and health insurance for the family. These requirements can be difficult to meet for those who have recently arrived in the country, are still learning the language, and may not yet have found employment that provides the necessary income level. In the Netherlands, for example, refugees and beneficiaries of subsidiary protection who do not apply within three months need to fulfil the criteria applicable for regular (non-refugee) applicants. When embassies in the country of origin or asylum can only provide an appointment several months later this may make it impossible to complete the application and all visa processing for the time limit to be met.[26]

The European Commission has encouraged EU Member States to follow the example of those “that do not apply the optional restrictions, or allow for more leniency, in recognition of the particular plight of refugees and the difficulties they often face in applying for family reunification.”[27] The Commission has also encouraged Member States when applying a time limit to “allow for the possibility of the sponsor submitting the application in the territory of the MS [Member State] to guarantee the effectiveness of the right to family reunification.”[28] In addition, the Commission has advised that when family reunification applicants face an objective practical difficulty to completing the process within three months, Member States “should allow them to make a partial application, to be completed as soon as documents become available or tracing is successfully completed.”[29]

Furthermore, UNHCR has called on Member States not to apply time limits to the more favourable conditions granted to refugees as “this limitation does not take sufficiently into account the particularities of the situation of beneficiaries of international protection or the special circumstances that have led to the separation of refugee families.”[30]

In practice, refugees may not be aware of the consequences of not applying within this timeframe. It is often very difficult for them to complete their family reunification applications within three months, including because of difficulties accessing the required supporting documentation such as national travel documents or those proving family links/dependency, accessing embassies by their family members to apply for family reunification from abroad, or being able to compile the necessary resources to meet the costs of the process and associated travel. In some cases, even tracing all family members following displacement or separation during travel can take time.

Good practices:

Bulgaria, France, Iceland, Italy, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and the United Kingdom do not apply the limited time frames in which refugees must apply for family reunification. Whilst Germany applies the three-month limit in order for applicants to benefit from the preferential terms, it has also developed an online mechanism for Syrian sponsors to register within this period while waiting for their embassy appointments.[31] In addition, persons seeking reunification to Germany can file their notification with an embassy or at a Foreigners’ Office in Germany. As long as the notification is filed within the three-month period, the family reunification application does not have to be completed in this period to benefit from the preferential terms.

UNHCR recommendation:

States should not apply time limits to the more favourable conditions for family reunification granted to refugees. As a minimum, time limits should only apply for the introduction of an application for family reunification and should not require that the applicant and family members provide all the documents needed within the three-month period or that the application needs to be lodged in person at the embassies abroad.

COUNTRIES WITH A TIME LIMIT FOR FAMILY REUNIFICATION APPLICATIONS

Austria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Sweden.

3. Difficulties accessing embassies abroad

A very practical difficulty many encounter relates to challenges accessing the relevant embassy to apply for or comply with the other necessary procedural steps for family reunification. Some EU+ embassies in key regions do not process family reunification applications and instead refer these to their embassies in a neighbouring state or elsewhere in the region. For example, the Swedish Embassy in Lebanon does not conduct interviews with Syrians thus requiring Syrians to apply elsewhere.[32] In Ethiopia, the Norwegian Embassy refers Eritrean applicants for family reunification to the Norwegian Embassy in Khartoum.[33] And in Iraq, the embassies of several EU+ countries refer applicants for family reunification visas to their embassies in Jordan or elsewhere.[34]

However, visa requirements make it very difficult for many, especially those with refugee status in the country where they live, to travel to a neighbouring state to apply.[35] Similarly, for those with family members still in Syria, most would have to apply in a neighbouring State as only two of the 32 States in the EU+ region still have a functioning embassy in Damascus at present. However, many often face visa restrictions, and sometimes protection risks,[36] when trying to cross to a neighbouring country, a situation that becomes more complicated if multiple visits to the embassy in the neighbouring country are required.[37] Female-headed families or other vulnerable profiles are especially impacted by these requirements. Elsewhere in the region, 18 EU+ States have no embassy in Baghdad, Iraq.[38] This challenge is further accentuated by a requirement by some EU+ States for applicants to have legal residence in the country in which they submit their reunification application. So for example, those living in countries where the concerned EU+ States do not have an embassy would thus have to travel to a neighbouring country and obtain legal residence,[39] usually for six months or more, in order to initiate or continue family reunification procedures. For many, this is an insurmountable barrier.

The EU Visa Code Regulation[40] provides for EU Member States to establish bilateral arrangements for representing each other to collect visa applications and issue visas. At least five EU Member States currently make use of this provision (see below). This could be far more widely used to address some of the challenges associated with lack of access to embassies in places from where refugees are seeking reunification.

In addition, those living far from embassies may face logistical, financial and even security challenges that inhibit access to embassies. Many also have to travel several times to the embassy, for example for the initial application, then to provide any outstanding supporting documents or attend an interview, and then finally to obtain the visa. Lastly, in addition to the access issues listed above, obtaining appointments at some embassies may also be very difficult in cases where embassies are receiving large volumes of visa applications in that particular country, resulting in extensive waiting periods.

Good practices:

Several States provide for the possibility of refugees being able to apply for family reunification on behalf of their family members who are outside Europe. For example, Estonia, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands provide for the possibility of applications either being lodged by the sponsor in the country of asylum or the intended beneficiaries abroad (including at Belgian Embassies for applicants seeking to reunify in Luxembourg). On the other hand, Bulgaria, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland all require the sponsor to first submit the application on their families’ behalf, although the family members abroad will then usually have to approach an embassy to complete the procedure, including to provide evidence of family links, confirm identity, or obtain the visa to travel. Still, this approach may help reduce the number of times family members abroad have to approach a European embassy. In addition to Luxembourg, other States that make allowances for applicants to complete formalities via another European embassy include Estonia, Finland, and Spain.

UNHCR recommendation:

States should allow sponsors to apply on behalf of their family, and waive the requirement for the family members outside Europe to confirm the application in an embassy. Where personal attendance at an embassy abroad is required, States should reduce the number of times that family members abroad need to approach an embassy, provide flexibility regarding appointments at embassies when individuals miss their appointments because of difficulties crossing borders or reaching the embassy, and strengthen efforts to ensure appointments are made closer together, especially when family members are traveling from far away from the embassy, so as to reduce the number of journeys required.[41] EU States should also make greater use of the provision that would enable family members outside of Europe to apply for and collect visas at the embassy of another EU State if the country to which they intend to travel has no consular representation where the family members live.

The Hardships of Separation for a Syrian Family

© UNHCR

Difficulties accessing embassies abroad & prohibitive costs

By Shpend Halili

Pristina, Kosovo – Syrian national Amira*, 43, never imagined that her journey to reunite with her husband in Germany would take her and her two daughters via Pristina, which was to be their home for eight months.

“We left Syria because there were daily bombings and it became very dangerous for us,” Amira said. “My husband left Syria in October 2015. He stayed for a while in Turkey then moved to Greece.”

Ali*, 45, continued onwards through the Balkans and then on to Germany, while his family waited anxiously for news. “For several days, we were unaware of his whereabouts until we managed to talk on the phone,” Amira told UNHCR.

In February this year, Amira and her two daughters flew to Kosovo after being issued a tourist visa and stayed with a family they had known prior to the Syrian conflict. Amira later approached UNHCR seeking help to reunify with her husband who had since been granted refugee status in Germany.

UNHCR and its implementing partner, Civil Rights Programme Kosovo (CRPK) supported Amira and her family as she sorted through the process of obtaining an appointment with the German Embassy, collecting the necessary documentation, finding a translator to assist with the interviews, as well as securing her temporary legal status in the country until the process was finalized. Further support was provided with the costs of the process, including administrative costs, the cost of the visas as well as the flights to Germany, an otherwise insurmountable obstacle for a family without a source of income.

As Amira waited for progress on her application, she worried about the impact of her journey on her daughters. “It has been more than a year that my daughters could not attend school. I am worried that for some time it will be difficult for them to continue their education,” said Amira.

As the process continued, Amira remained anxious, feeling the impact of the prolonged separation of her family. She had not seen her husband in almost two years. At the same time, news from home in Syria was troubling. “I still have family members, my mother, brother and others in Syria. They live in fear,” she said. “I wish that the war will stop and life can become the same as it was before.”

Finally, the family’s visas were granted and they could make their way to Germany. “My husband is not working, but he is safe in Germany and we are happy that will reunite with him after such a long and difficult time,” said Amira. While more challenges lie in store for the family, at least they can face these together and in safety.

*Name changed for protection reason

4. Lack of information and assistance in navigating complex procedures

Family reunification application processes are often complex with EU Member States having different application requirements. Those seeking an explanation or clarification of some requirements may have limited access to information in a language they understand or that provides sufficient detail. Any resulting mistakes in their applications may have the effect of delaying or denying their application for reunification. Refugees may sometimes be given information that does not take into account the more favourable requirements for refugees (such as not having to meet the income, accommodation, insurance and integration criteria) or clearly stating the timeframes in which to apply in order to benefit from the favourable conditions.[42]

The European Commission has recognized the need for such clear information and has called on EU Member States to “develop a set of rules governing the procedure for examination of applications for family reunification which should be effective and manageable, as well as transparent and fair” and “practical guides with detailed, accurate, clear information for applicants, and to communicate any new developments in a timely and clear manner.” It has noted the need for such guides to “be made widely available, including online and in places where applications are made” and to be “available in the language of the [Member State], in the local language in the place of application, and in English.”[43]

UNHCR mapping and analysis[44] of family reunification procedures across Europe indicates that there is adequate information available regarding the right to family reunification in only seven of the 32 countries in the EU+ region.[45] Some NGO support and assistance during the family reunification process is available in 24 of the countries,[46] although the capacity to provide such assistance varies significantly from one country to another.

Good practice examples:

As one example of good practice, Germany’s Federal Foreign Office (FFO) has established several Family Assistance Programme service centres with IOM in countries where many of those granted international protection in Germany have family members. Service centres assisting Syrian family reunification applicants have been established in Istanbul and Gaziantep in Turkey, and Beirut and Chtoura in Lebanon, and for Iraqi applicants in Erbil, Iraq.[47] These service centres provide information on the procedures, conduct pre-screening of applications to advise applicants of any missing or incomplete documentation, and provide support services including for passport photos and printing, as well as facilitating on-site DNA collection for testing in cases where further proof of a biological relationship is required. This range of services supports German Consular Offices with the management of applications and helps reduce waiting times for applicants. Linked to this, the FFO supported IOM to establish a counselling position in Berlin to support applicants already in Germany.

In addition, prior to the establishment of the service centres, the German government also created an online form for Syrian refugees seeking family reunification with information about the procedures and to facilitate easier applications.[48] The form is available in German, English and Arabic.

UNHCR recommendation:

EU+ States should provide detailed guidance for beneficiaries of international protection on how to apply for family reunification, including regarding the favourable conditions applicable to refugees, in a manner and language that they can understand.

“Daddy isn’t here!”

© UNHCR/Chris Melzer

An Eritrean boy in Germany waits for his father

By Chris Melzer

Mickey was born in Ethiopia to Eritrean parents. Before he’d even turned three, he’d crossed half a dozen countries, been held in a prison in Libya, survived deadly journey across the Mediterranean and reached safety in Germany. Life was better, except that Mickey kept repeating, “Daddy isn’t here!” It broke his mother’s heart.

Mickey is now six and his mother Feyori, 23, and father Amanuel, 31, have finally been reunited in Germany and can tell their story.

The couple fled Eritrea when Feyori, whom Amanuel had married in a traditional ceremony, was pregnant and Mickey was born in Ethiopia.

Believing they had a better chance of reaching Europe if they travelled separately, Feyori and Mickey went on ahead to Libya but found themselves put in prison.

“They wanted money,” she tells UNHCR. Feyori paid the money, was released, and continued on the perilous journey across the Mediterranean. “Four days,” she says quietly, hugging Mickey closer. “Four days filled with fear.”

Finally, Feyori and Mickey reached Italy and made their way to Germany. They were accommodated in Pulheim, near Cologne. Mickey was enrolled in the local kindergarten and quickly learnt German and was soon able to translate for his mother. But still they missed Amanuel.

“‘Daddy isn’t here,’ Mickey used to say,” Feyori recounts, “And then one day he said, ‘Daddy isn’t coming anymore.’” Even children give up hope eventually.

Meanwhile Amanuel was stuck in Israel. “It was the only country I was able to reach by an overland route,” he says from their home in Pulheim. But he desperately wanted to join his family in Germany.

Because Amanuel and Feyori had a traditional wedding, without paperwork, the family reunification process was difficult, despite a DNA test proving Amenual was Mickey’s father.

Germany requires Eritrean citizens to have their traditional marriages registered by the state and DNA confirmation of paternity is not enough for visas to be granted.

“Feyori and I tried everything,” Amanuel remembers.

Every document had to be translated, certified and sent to Israel. But the family did not give up and this spring, Amanuel was finally able to join his wife and son in Germany.

When Amanuel stepped off the plane, everything seemed foreign, except his loved ones. On the train, Mickey told his dad about life in Germany.

“Germany is a good country,” says Mickey. “When I grow up, I want to be a policeman. But I will never forget that I come from the Land of the Lion.”

Feyori and Amanuel now live in a small apartment in Pulheim. The walls are decorated with images of saints in pop-art style and one frame with ten photos. The word ‘family’ is written on top.

“I’m grateful for everything Germany has done,” says Feyori. “And I’m proud that next February, Mickey will have a little brother, the first member of our family to be born in Germany!”

Mickey would have preferred a sister but a brother will do. Essentially, what matters most is that Daddy is finally here.

5. Difficulties proving family links or dependency and lack of access to documents

Proving family links or dependency may be particularly difficult especially where documentary evidence such as passports, birth certificates, marriage certificates or other such documents are missing and/or hard to access. In the same way, lack of documentation in the case of informal adoption of non-biological children may also delay or lead to a rejection of reunification. In the case of single parent families, they may have to provide proof of the death of the other parent and/or of parental authority, which may not be possible where the other parent remains in a conflict zone or such administrative services are no longer available from the State or prohibitively costly.[49]

The Family Reunification Directive specifically states that “a decision rejecting an application may not be based solely on the fact that documentary evidence is lacking.”[50] Similarly, UNHCR’s governing Executive Committee[51] has issued Conclusions stating that “when deciding on family reunification, the absence of documentary proof of the formal validity of a marriage or of the filiation of children should not per se be considered as an impediment.”[52] However, many EU Member States by law or practice only accept official documents. For some refugees, obtaining a passport, marriage or birth certificate, or criminal background check means approaching their embassy in the country to which they have fled, which might expose them or their family members still in their country of origin to protection risks.[53]

UNHCR’s analysis shows that nine of the 32 countries in the EU+ region[54] routinely require official documents without offering flexibility when such documents are not available, although the Family Reunification Directive obliges Member States to take other evidence into consideration. UNHCR and the European Commission have called on Member States to adopt clear rules governing evidentiary requirements.[55] While EU Member States have a certain margin of appreciation to determine if it is necessary and appropriate to verify family relationships through interviews or other means, including DNA testing, the European Commission has stated in its guidance that “the appropriateness and necessity criteria imply that such investigations are not allowed if there are other suitable and less restrictive means to establish the existence of a family relationship.”[56] Where DNA testing is required as a last resort, the European Commission has encouraged Member States to consider the particular situation of refugees and bear the costs of any required DNA testing so that the costs of such tests do not become an obstacle to reunification.[57] DNA tests may be required as evidence in 16 of the 32 countries in the EU+ region, according to UNHCR’s mapping and analysis.[58] UNHCR has issued guidance on the use of DNA testing to establish family relationships in the refugee context so as to safeguard dignity and human rights as well as to ensure full respect for the principle of family unity.[59]

Good practice examples:

Some States in the EU+ region have adopted a more flexible approach to documentation requirements in recognition of the fact that evidence may have been lost in the course of flight and/or may not be available from some States. For example, Bulgaria allows applicants to provide a declaration certified by a notary with the names, dates of birth and addresses of the persons seeking reunification in the absence of marriage or birth certificates. Finland requires applicants to provide a written explanation if they are unable to provide documentary evidence of their identity or family ties, and further clarifications may be sought by Finnish authorities, including through an interview. In Austria, the asylum authority reimburses the costs of the DNA analysis upon application if the claimed family relationship was confirmed by the expert findings and if the applicant is resident in Austria.

UNHCR recommendation:

States should take account of the unique situation of refugees and persons holding other forms of an international protection status, who – for reasons related to their flight – do often not possess documents to prove their identity and family relationships, and may not be able to access the administrative services of their country, including for protection reasons. Consequently, they will often not be able to meet all documentary requirements. The absence of documentation to support the existence of a family link should not per se be a barrier to family reunification. To address the identified concerns, the European Union should develop common guidelines on establishing identity and family links.

COUNTRIES ACCEPTING ONLY OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS AS PROOF OF FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS

Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Hungary, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, and Slovakia.

6. Access to travel documents and prohibitive travel and other costs

Two countries in the EU+ region[60] require national passports as travel documents without providing an option for other travel documents such as a UN Convention Travel Document, a laissez-passer, or International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) travel documents.

However, obtaining the required national passport in order to travel for family reunification to an EU Member State may be problematic, especially where the concerned family members remain in the country of origin and fear persecution at the hands of state agents. UNHCR is aware of cases where family members in the country of origin have been imprisoned after approaching government authorities for travel documents.[61] In other instances, it can be particularly difficult for family members in a country of asylum to obtain passports. For example, as there is no Eritrean Embassy in Ethiopia, Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia who require passports for family reunification have to choose between undertaking a dangerous irregular journey to Sudan to seek a passport through the embassy there or else returning to Eritrea to apply for a passport.

In addition, obtaining other travel documents and visas for family reunification travel may be difficult because of the obstacles preventing access to an embassy described above, and because few Member States make provision for visas to be issued upon arrival upon the presentation of a valid travel document, including a laissez-passer.

The European Commission has recognized these challenges and called for Member States to “recognise and accept ICRC emergency travel documents and UN Convention Travel Documents, issue one-way laissez-passer documents, and offer family members the possibility of being issued a visa upon arrival in the [Member State]” in cases where it is impossible for refugees and family members to obtain the required travel documents and visas.[62] Likewise, UNHCR has urged EU Member States as a minimum to put in place in law and in practice alternative mechanisms when national travel documents are not accepted or not available, including the use of UN Convention Travel Documents (where available, as not all asylum countries are parties to the 1951 Convention) or emergency ICRC travel documents.[63]

Finally, the process of applying for family reunification can be prohibitively expensive in terms of travel costs, translation of documents, medical checks, and visa and passport fees. In some EU Member States, visa fees may be over €100. In addition, some may face additional administrative fees of up to €350.[64] Only three of the 32 countries[65] in the EU+ region offer the opportunity for refugees to be reimbursed for travel costs associated with family reunification. Refugees in other EU Member States may be unable to afford the high costs, including because they have had limited opportunities for employment while waiting for their asylum applications to be processed. Likewise, their family members seeking reunification may themselves be refugees in another country and may have limited legal or practical opportunities for employment, thus also rendering them unable to afford the high costs. At present, specialized financial assistance services that support families with the cost of family reunification in the EU are very limited.

Good practice:

In cases where national travel documents are not available, several States make provisions to issue a one-way travel document, including France, Germany,[66] Ireland,[67] Italy,[68] the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Sweden and the United Kingdom.[69]

In terms of assisting with travel costs, in Spain, the Ministry of Health and Social Services provides some funding for three NGOs that support family reunification through providing information, legal advice and support with the administrative procedures, financial support for travel of family members to Spain for reunification, initial financial support following the arrival of family members in Spain, as well as legal and social support for families’ integration in Spain.

UNHCR recommendation:

To overcome the difficulties associated with lack of access to national travel documents, where States have already approved family reunification, they should also facilitate travel by issuing temporary travel documents or accepting UN Convention Travel Documents (where available) or travel documents issued by the ICRC.

In terms of helping to overcome the obstacle created by the high costs of reunification, the European Union should establish a revolving fund to facilitate family reunification for those who are unable to cover the fees.

Forced to wait

© UNHCR/Stefanie J. Steindl

Those with subsidiary protection have delayed and more limited access

By Ruth Schoeffl

Abdi from Somalia was only 15 when he arrived in Europe after being kidnapped by rebels in an attempt to forcibly recruit him. At his mother’s insistence, he crossed the border to Ethiopia, then travelled via Turkey, Greece and Italy by plane and boat until he reached Austria where he applied for asylum. As he waited for the outcome of his asylum application, Abdi tried to find out news of his mother, brothers and sisters whom he had not been able to contact since he left Somalia.

Abdi had been granted subsidiary protection rather than refugee status in Austria. This means that he faced the mandatory waiting period of three years (two years in some other European countries) before he can apply for family reunification. By the time he is eligible to apply Abdi will be over 18 and will no longer have the right as an unaccompanied child to bring his family members to join him.

7. Delayed and more limited access to beneficiaries of subsidiary protection and other complementary forms of protection

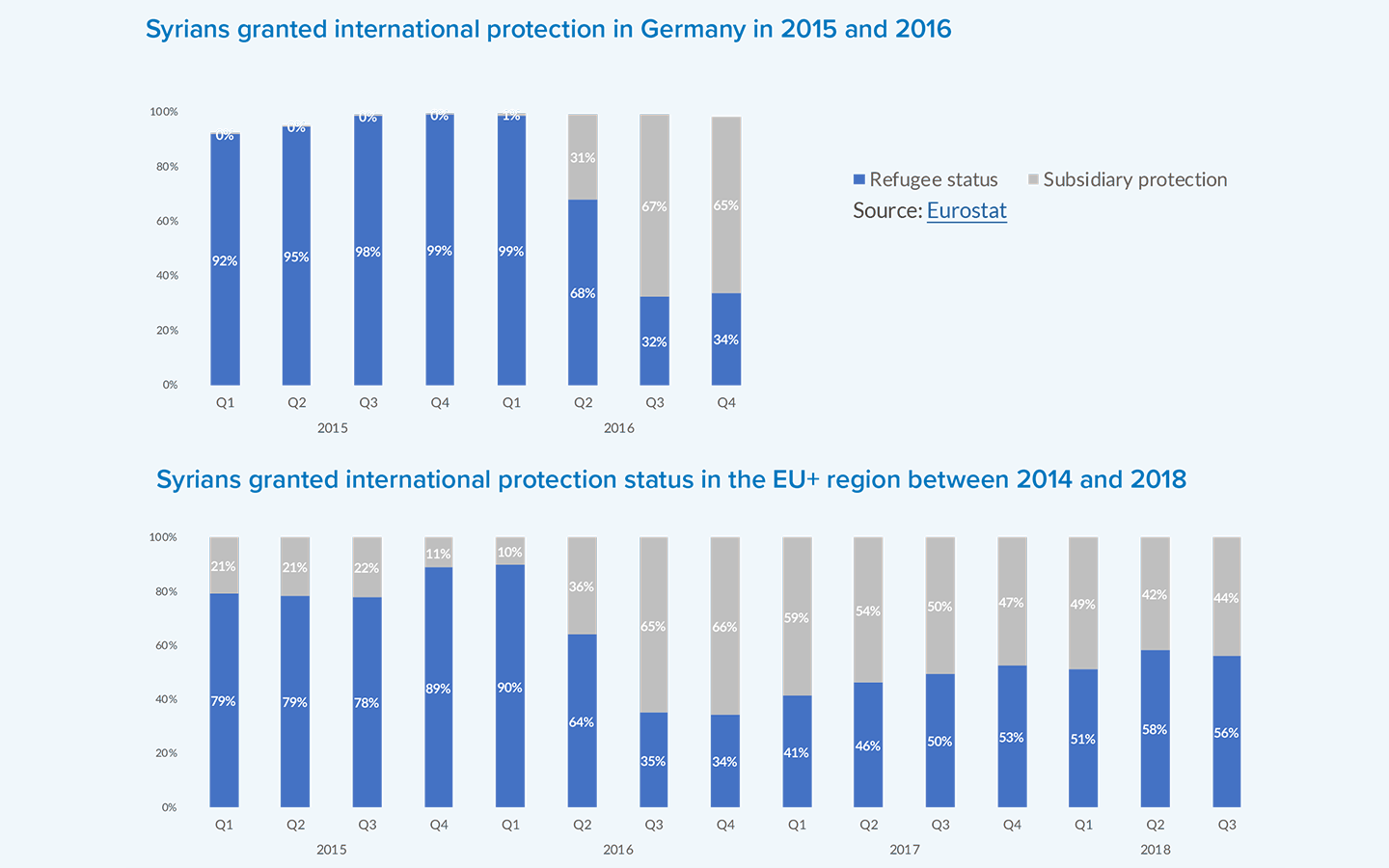

Several EU Member States have granted subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection rather than refugee status to many Syrians, the top country of origin of those entering Europe to seek asylum in 2015, when just over a million people arrived by sea.[70] In Germany,[71] a change in procedural design in March 2016 resulted in an increased proportion of successful international protection applicants from Syria being granted subsidiary protection rather than refugee status. For example, while less than 1% of Syrian applicants each quarter in 2015 were granted subsidiary protection, this proportion rose to 67% in the third quarter of 2016.

Following this, the proportion of Syrian applicants granted subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection in the EU+ region also increased from a high of 22% in the third quarter of 2015 to 66% in the fourth quarter of 2016 with potentially negative implications for family reunification.

UNHCR has stated its position on several occasions that many of those being granted subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection are likely to meet the criteria of the refugee definition in the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. Notably, UNHCR’s international protection guidelines have called on States to first assess whether persons fleeing situations of armed conflict and violence qualify for refugee status, and to only apply subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection to those who do not.[72] In particular with regard to the Syrian conflict, UNHCR has characterized “the flight of civilians from Syria as a refugee movement, with the vast majority of Syrian asylum-seekers continuing to be in need of international refugee protection, fulfilling the requirements of the refugee definition contained in Article 1A(2) of the 1951 Convention.”[73]

Seventeen of the 32 States in the EU+ region apply the same conditions for family reunification to those with refugee status and beneficiaries of subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection. However, as the favourable conditions set out in Chapter V of the Family Reunification Directive refer to refugee status, in fifteen States[74] in the EU+ region, beneficiaries of subsidiary protection (or other complementary forms of protection in the case of Liechtenstein and Switzerland)[75] cannot access family reunification on the same basis as those granted refugee status. Of these, five States[76] have introduced a mandatory waiting period of between two and three years before an application for family reunification can be lodged and Germany and Sweden temporarily suspended family reunification for this group for a set period. Germany’s temporary suspension of this right since March 2016 ended on 31 July 2018[77] while at present, Sweden’s temporary suspension since July 2016 is due to end in July 2019.[78] As a result, thousands of people with recognized international protection needs who have already spent many months or years separated from their families during their journeys and while waiting for the outcome of their asylum applications are now required to wait an additional period before being able to apply for family reunification. In practice, the waiting will be even longer due to processing times and waiting times for appointments for family members in embassies abroad, if they are able to successfully navigate the various other obstacles outlined below. Similarly, the Czech Republic requires a mandatory period of legal residence of 15 months prior to allowing applications for family reunification.[79] In addition, in Cyprus, Greece, and Malta, beneficiaries of subsidiary protection do not have the right to family reunification at all.[80]

Of the others, Hungary and Slovakia do not extend the favourable conditions granted to refugees to subsidiary protection holders, which means that subsidiary protection holders are also required to show evidence that they have:

- Housing that meets a required standard;

- Health insurance for the sponsor and members of the family; and

- The necessary income and resources to maintain the family.[81]

UNHCR considers that the international protection needs and experience of having to leave their countries of persons benefiting from subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection are often very similar to those of refugees. As with refugees, subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection beneficiaries are unable to return to their countries of origin or previous habitual residence (in case of stateless persons) due to the risk of serious harm. As a result, there is usually no valid reason to distinguish between the two groups as regards their right to family life and conditions of access to family reunification, especially given the fact that the practices of different EU Member States vary significantly with regard to granting refugee status or subsidiary protection to persons with the same or similar profiles.

In December 2016, UNHCR High Commissioner Filippo Grandi highlighted the need for European States to “accord the same rights to family reunification to those granted subsidiary forms of protection as are given to refugees.”[82] Similarly, the European Commission has also stated that it “considers that the humanitarian protection needs of persons benefiting from subsidiary protection do not differ from those of refugees, and encourages [Member States] to adopt rules that grant similar rights to refugees and beneficiaries of temporary or subsidiary protection.”[83]

In addition, the current 2011 Qualification Directive specifically notes that “beneficiaries of subsidiary protection status should be granted the same rights and benefits as those enjoyed by refugees under this Directive, and should be subject to the same conditions of eligibility.”[84] The European Commission has also noted that “even when a situation is not covered by European Union law, Member States are still obliged to respect Article 8 [Right to respect for private and family life] and 14 [Prohibition of discrimination] ECHR [European Convention on Human Rights].”[85] Similarly, the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights noted in 2017 that “differences in treatment between 1951 Convention refugees and subsidiary protection beneficiaries are difficult to square with Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights (and indeed with the analogous EU general principle of equality and non-discrimination) and so should be reconsidered promptly.”[86]

Good practice examples:

The majority of States within the EU+ region grant access to family reunification for persons holding subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection status on the same basis as those with refugee status. Thus, in Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, France, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and the United Kingdom, those with subsidiary protection or similar status can apply for family reunification on the same basis as those with refugee status. According to Eurostat data, in 2016, Italy issued almost 5,600 residence permits for those reuniting with a family member with subsidiary protection in Italy, while Belgium issued just over 1,000.[87]

UNHCR’s recommendation:

Ensure that beneficiaries of subsidiary protection or other forms of complementary protection (in Liechtenstein and Switzerland) have access to family reunification on the same basis and under the same favourable rules as those applied to refugees. This should include the favourable rules that apply to refugees regarding not having to meet self-sufficiency requirements, ending temporary suspensions and removing numerical limits on the right to family reunification, and abolishing the two or three-year mandatory waiting periods.

COUNTRIES THAT DO NOT GRANT ACCESS TO FAMILY REUNIFICATION FOR BENEFICIARIES OF SUBSIDIARY PROTECTION OR OTHER FORMS OF COMPLIMENTARY PROTECTION ON THE SAME BASIS AS REFUGEES

Austria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Malta, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland

UNHCR and Partners’ Activities on Family Reunification

Three of the Al-Bashawat siblings (from left) Fatima, Ali and Amal settle in to their new home, after being reunited with their father in Vienna. © UNHCR/Stefanie J. Steindl

To assist with family reunification for refugees, UNHCR and its partners in Europe have undertaken a number of activities aimed at supporting individuals with the procedures and identifying steps government counterparts could take to help address some of the barriers.

In several countries, including Austria,[88] Bulgaria,[89] the Czech Republic, Germany,[90] Hungary,[91] Italy,[92] Portugal,[93] and Romania, [94] UNHCR and/or its project partners have developed specific guidance on the family reunification process, its requirements and how to navigate the procedures in languages accessible to refugees.

UNHCR offices and/or project partners have also regularly intervened in complex cases, including by providing direct assistance in the application process, engaging with government counterparts or embassies, providing legal counselling, engaging in legal interventions, including by appealing negative decisions. This assistance has been provided in Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Spain and the United Kingdom. In Ireland, UNHCR, the Irish Red Cross and IOM have jointly provided travel assistance since 2006 to help refugees overcome the financial obstacles associated with the travel costs for family reunification. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the British Red Cross, with support from UNHCR, assists a large proportion of successful applicants for refugee family reunion by facilitating travel to the United Kingdom (including arranging travel and paying costs).

Additionally, in several countries, UNHCR has produced or supported the development of materials or reports highlighting the difficulties faced by refugees in the family reunification process, including in Austria,[95] Germany,[96] Norway,[97] Sweden,[98] Switzerland,[99] the United Kingdom,[100] as well as one covering the Central Europe region.[101] UNHCR also meets regularly with national authorities and otherwise advocates to find ways of overcoming challenges associated with family reunification.

Lastly, UNHCR also provides training with components on family reunification as required, including in partnership with its project partners such as the Portuguese High Commission for Migration (ACM) in Portugal or the German Red Cross on family tracing in Germany.

© UNHCR

13 YEARS APART

Expense and complex procedures can keep families apart for years

Morgan and Marvin were aged just one and three when their mother Roberte was forced to flee the Central African Republic (CAR) in 2005. They are finally reunited early one morning in November 2018 at Paris Charles de Gaulle airport. The reunion is emotional after years of struggle and administrative efforts. “Today is the start of my life,” says Roberte, a refugee in France.

The boys fled violence in the CAR in 2015 and lived with temporary foster families in Cameroon until all the documents were ready for them to be reunited with her mother in France. Morgan and Marvin, now aged 14 and 16, are delighted to be reunited with their mother and the rest of the family, including their grandmother and their aunts, all of whom live in Paris.

Summary of Recommendations

As a means of addressing the obstacles identified above, UNHCR recommends the following:

To European States:

- Expand the scope of family reunification

by consistently applying a broader definition of family, prioritizing dependency as the primary criterion, including in relation to unaccompanied children and reunification with their parents and other family members; - Ensure that beneficiaries of subsidiary protection (or other forms of complementary protection in Liechtenstein and Switzerland) have access to family reunification on the same basis and under the same favourable rules as those applied to refugees. This includes extending the favourable rules that apply to refugees regarding not having to meet the self-sufficiency requirements, ending temporary suspensions and removing numerical limits on the right to family reunification, and abolishing the two or three-year mandatory waiting periods;

- Refrain from applying time limits to the more favourable conditions granted to refugees. As a minimum, time limits should only apply for the introduction of an application for family reunification and should not require that the applicant and family member provide all the documents needed within the three-month period or that the application needs to be lodged in person at the embassies abroad;

- To address challenges associated with limited access to embassies, grant the sponsor the option to apply on behalf of his or her family, and waive the requirement for family members outside Europe to confirm the application in an embassy. Where personal attendance at an embassy abroad is required, States should reduce the number of times that family members abroad need to approach an embassy, provide flexibility regarding appointments at embassies when individuals miss their appointments because of difficulties crossing borders or reaching the embassy; and strengthen efforts to ensure appointments are made closer together.[102] EU States should also make greater use of the provisions on bilateral arrangements in the EU Visa Code Regulation to enable family members outside of Europe to apply for and collect visas at the embassy of another EU State if the country to which they intend to travel has no consular representation where the family members live.

- Provide detailed guidance for beneficiaries of international protection on how to apply for family reunification, including regarding the favourable conditions applicable to refugees, in a manner and language that they understand.

- Take account of the unique situation of refugees and persons holding other forms of an international protection status, who for reasons related to their flight, often do not possess documents to prove their identity and family relationships, and may not be able to access the administrative services of their country, including for protection reasons. Consequently, they will often not be able to meet all documentary requirements. The absence of documentation to support the existence of a family link should not per se be a barrier to family reunification; and

- To overcome the difficulties associated with lack of access to national travel documents, where States have already approved family reunification, these States should also facilitate travel by issuing temporary travel documents or accepting UN Convention Travel Documents (where available) or travel documents issued by the ICRC.

To the European Union institutions:

- Develop common guidelines on establishing identity and family links; and

- Establish a revolving fund to assist refugees with meeting the costs associated with family reunification for those who are unable to cover the fees.

Sources

[1] This report focuses on family reunification involving persons granted international protection in Europe and family members outside of Europe. It does not specifically address the challenges involved in family reunion, which is the process through which persons granted international protection in one EU Member State may seek to bring family members already in another EU Member State to join them according to the Dublin III Regulation.

[2] In the same period, Italy issued 16,200 permits for reunification with family members of those granted refugee status or subsidiary protection, see Eurostat, First permits issued for family reunification with a beneficiary of protection status, 24 October 2018, http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=migr_resfrps1&lang=en. Similarly, between July 2017 and June 2018, the United Kingdom granted 5,963 visas to individuals on the basis that they were the family members of persons granted asylum or humanitarian protection in the United Kingdom, see Home Office, Summary of latest statistics, 23 August 2018, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/immigration-statistics-year-ending-june-2018/summary-of-latest-statistics#how-many-people-do-we-grant-asylum-or-protection-to.

[3] Eurostat, First permits issued for family reunification with a beneficiary of protection status.

[4]Council of the European Union, Council Directive 2003/86/EC of 22 September 2003 on the right to family reunification, 22 September 2003, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32003L0086&from=en

[5] Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom.

[6]‘Refugee status’ under EU law reflects the refugee definition in the 1951 Refugee Convention.

[7] Subsidiary protection is a form of complementary protection not defined as such under international law but largely shaped by international obligations such as Art. 3 of the UN Convention Against Torture, Art. 7 of the International Covenant on Political and Civil Rights as well as Art. 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights. EU law however defines the term under Art. 2 f) and g) of the EU Qualification Directive as a “person eligible for subsidiary protection” who is a third-country national or a stateless person who does not qualify as a refugee but in respect of whom substantial grounds have been shown for believing that the person concerned, if returned to his or her country of origin, or in the case of a stateless person, to his or her country of former habitual residence, would face a real risk of suffering serious harm or, owing to such risk, is unwilling to avail himself or herself of the protection of that country.

[8] While the concept of subsidiary protection does not exist in Swiss and Liechtenstein law, persons in need of international protection may be granted an F-permit, which comes with a mandatory three-year waiting period before holders can apply for family reunification.

[9] An overview of some of the risks refugees face travelling to and through Europe are available here – UNHCR, Desperate Journeys – January to August 2018, September 2018, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/65373.

[10] UNHCR, The Right to Family Life and Family Unity of Refugees and Others in Need of International Protection and the Family Definition Applied, January 2018, http://www.refworld.org/docid/5a9029f04.html.

[11] Council of the European Union, Council Directive 2003/86/EC of 22 September 2003 on the right to family reunification.

[13] European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on guidance for application of Directive 2003/86/EC on the right to family reunification, 3 April 2014, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:2d6d4b3c-bbbc-11e3-86f9-01aa75ed71a1.0001.01/DOC_1&format=PDF (page 24)

[14] As noted before, the Directive does not apply to EU Member States Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom as these three States opted out of the Directive. Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland are not EU Member States, so the legislation does also not apply.

[15] In the context of refugee status determination, UNHCR uses the term “close” family members in lieu of “nuclear” family members as it more neutrally and accurately reflects the categories of family members for whom a relationship of social, emotional or economic dependency is presumed, see UNHCR, UNHCR RSD Procedural Standards – Processing Claims Based on the Right to Family Unity, 2016, http://www.refworld.org/docid/577e17944.html, para. 5.2.3.

[16]European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on guidance for application of Directive 2003/86/EC on the right to family reunification, page 22.

[17] Cyprus, Latvia, Malta, Poland and Slovakia.

[18] UNHCR, Refugees in Austria yearn for loved ones left behind, 3 April 2017, http://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/2017/4/58e253754/refugees-austria-yearn-loved-ones-behind.html.

[19] UNHCR, UNHCR’s Response to the European Commission Green Paper on the Right to Family Reunification of Third Country Nationals Living in the European Union (Directive 2003/86/EC), February 2012, http://www.refworld.org/docid/4f55e1cf2.html.

[20] In Ireland, reunification with parents and siblings can be possible if the sponsor is under 18 and not married on the date they submitted the family reunification application and siblings must be under 18 and not married at the time of submission of the family reunification application.

[21] As previously noted, this right does not exist in Liechtenstein, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

[22] UNHCR, Legal considerations regarding access to protection and a connection between the refugee and the third country in the context of return or transfer to safe third countries, April 2018, https://www.refworld.org/docid/5acb33ad4.html. This document sets out the standards of protection and access to rights that should be in place in a third country to which a refugee is returned or transferred.

[23] Austria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Liechtenstein, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Switzerland, Sweden, and United Kingdom. In the United Kingdom, the requirement is that the family members were part of the family unit before their sponsor fled the country of origin.

[24] See Court of Justice of the European Union, Judgment in Case C-550/16: A and S v Staatssecretaris van Veiligheid en Justitie, 12 April 2018, https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2018-04/cp180040en.pdf.

[25] Austria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Sweden.

[26] UNHCR, ‘The “Essential Right” to Family Unity of Refugees and Others in Need of International Protection in the Context of Family Reunification”, January 2018, http://www.refworld.org/docid/5a902a9b4.html.