The fighting inside Sudan is having devastating humanitarian effects both inside the country and in the wider region.

South Sudanese returnees and Sudanese refugees who fled the conflict board trucks at the Joda border point near Renk, South Sudan. ©UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

For civilians caught in the crossfire, the consequences have been catastrophic. Hundreds of people have been killed and many more injured, hundreds of thousands have been displaced, health facilities have come under attack and the prices of food, fuel and other basics have skyrocketed.

The fighting has created a humanitarian emergency both inside Sudan and in neighbouring countries such as Chad, South Sudan and Egypt, where large numbers of people are fleeing in search of safety.

Without a swift and peaceful resolution, the repercussions will be devastating for Sudan and the wider region, both of which were already struggling to cope with mass displacement, economic turmoil and climate shocks before the latest crisis erupted.

Here is a look at the humanitarian context behind the current crisis, its projected impact on civilians and what UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, and its partners are doing to respond.

The recent fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Reaction Forces comes at a time when Sudan was already experiencing its highest levels of humanitarian need in a decade.

The removal of long-time authoritarian leader Omar al-Bashir in 2019 brought optimism that the country would be returned to civilian rule. However, a military coup two years later dissolved the transitional civilian government sparking political and economic turmoil and reigniting intercommunal conflict in the western Darfur region and Blue Nile and Kordofan states.

In addition, extreme weather linked to climate change, including floods and droughts, has affected hundreds of thousands of people across the country, destroying crops and livestock and making it increasingly difficult for families to put food on the table.

Sudan has been grappling with conflict and displacement since the start of the Darfur crisis in 2003. By the end of 2022, over 3.7 million people were internally displaced, with the majority living in camps in Darfur. Another 800,000 Sudanese were living as refugees in neighbouring countries such as Chad, South Sudan, Egypt and Ethiopia.

At the same time, the country was home to over 1 million refugees – the second-highest refugee population in Africa. The majority were from South Sudan and lived in Khartoum and White Nile States but refugees fleeing the crisis in northern Ethiopia starting in late 2020 also found refuge in eastern Sudan and others came from Eritrea, Syria and the Central African Republic.

Some of those now fleeing the country are refugees attempting to return home or to other neighbouring countries, even if that means going to areas that are far from stable or ready to receive them.

In the first four weeks of the crisis, around 200,000 refugees and returnees fled the country while another 700,000 people were displaced inside Sudan.

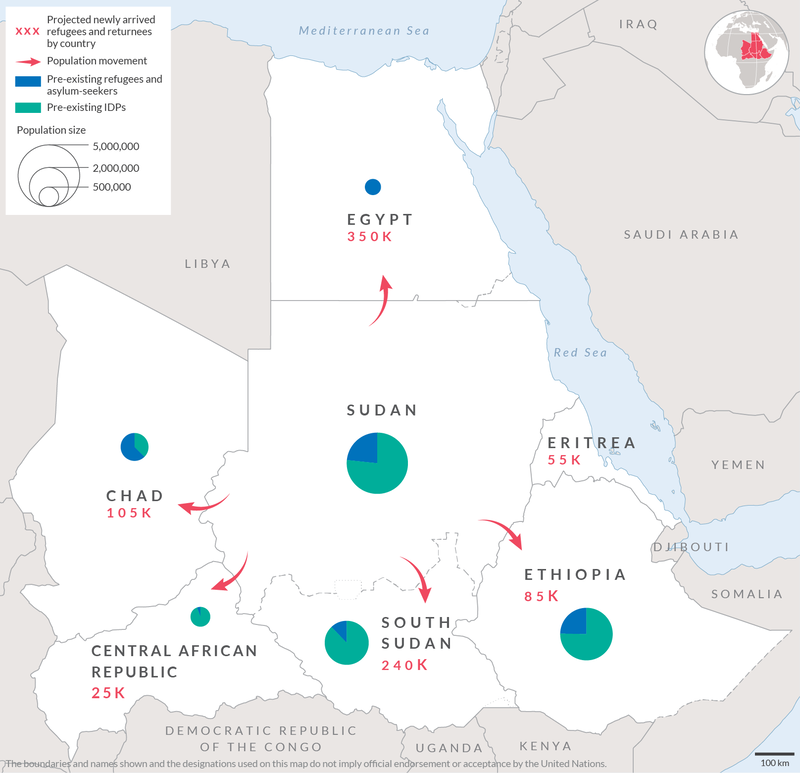

Egypt has received the largest number of people, followed by Chad, South Sudan, the Central African Republic and Ethiopia. In South Sudan, those arriving are mainly returning nationals who had been living in Sudan as refugees.

Without a resolution to the crisis, many hundreds of thousands more people will be forced to flee in search of safety and basic assistance. UNHCR and its partners estimate that the number of refugees and returnees could reach 860,000 by October.

All the neighbouring countries impacted by this new emergency were already hosting large numbers of refugees and internally displaced people on insufficient and dwindling levels of humanitarian funding. At the same time, countries like Chad and South Sudan (the two least developed countries in the world) were battling hunger, insecurity, and the impacts of climate change.

Now the conflict is disrupting trade and supply chains, pushing up the costs of food and fuel.

Those crossing borders, most of them women and children, are arriving in urgent need of food, water, shelter, healthcare and basic items like blankets, cooking utensils and soap. Psychosocial support for parents and children who have witnessed or experienced appalling violence is another priority, as is putting mechanisms in place to prevent and respond to gender-based violence.

With the rainy season due to begin in a few weeks, the race is on to preposition aid before roads to remote border regions become impassable, cutting off newly arrived refugees from assistance.

Several years of devastating floods in South Sudan have already damaged roads making it almost impossible for returning refugees to travel from the border to home areas. Those that do make it home are likely to find fragile communities still recovering from years of conflict.

UNHCR has emergency teams in neighbouring countries and is working with national authorities and partners to register new arrivals, ensure their most immediate needs are met and relocate them away from border areas. But this is just the beginning.

UNHCR and its partners initially estimated that they will need $445 million to respond to the needs of people fleeing Sudan in the coming months, but that figure is likely to rise when a detailed response plan is published in the coming days.

Inside Sudan, the clashes in Khartoum and Darfur have restricted the ability of UNHCR and other aid agencies to deliver assistance. In addition, supplies of aid have been looted. In areas where the security situation is calmer, UNHCR has been able to visit refugee settlements and is working with Sudan’s Commission for Refugees to continue providing protection and assistance. Water and basic health assistance is still available, and the World Food Programme has restarted distributions of food assistance in refugee camps in the East

UNHCR is urgently calling on the international community for new funding to respond to the mounting crisis.

“The needs are vast, and the challenges are numerous,” says Raouf Mazou, UNHCR’s Assistant High Commissioner for Operations. “If the crisis continues, peace and stability across the region could be at stake.”

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter