DESPERATE JOURNEYS

Refugees and migrants arriving in Europe and at Europe's bordersJANUARY – AUGUST 2018

Refugees and migrants rescued at sea after departing from Libya disembark from the NGO vessel Aquarius at the Spanish port of Valencia on 17 June 2018 after spending over a week at sea having been refused permission to land elsewhere. Among them were more than 120 unaccompanied and separated children. © UNHCR/Markel Redondo

Khaled Hosseini, UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador. © UNHCR / Paul Wu

Foreword

By Khaled Hosseini, UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador

On the 2nd of September 2015, three-year-old Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi drowned in the Mediterranean. As a father of two, when I saw the photo of little Alan’s body lying limp on a Turkish beach, I tried to imagine how bludgeoning the loss must be to his father, who also lost his wife and another son on that same fateful day. How did he endure seeing again and again photos of his boy’s lifeless body lifted from the sand by a stranger, a person who did not know Alan’s voice, or his laughter, or his favourite toy?

In my own way, I wanted to pay tribute to him, to Alan, and to the thousands who have died in their attempt to find sanctuary away from violence, conflict, and persecution. In Sea Prayer, an imagined letter from a father to his son on the eve of making the sea crossing to Europe, I hoped to create a picture of the unfathomable despair that forces countless families to risk all they have in search of hope and safety on foreign shores.

Khaled Hosseini, UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador.© UNHCR / Paul Wu

On a recent visit to Lebanon and Italy with UNHCR, The UN Refugee Agency, the images I saw when writing Sea Prayer were played out again and again in the lives of the refugees that I met. In Lebanon, I spent time with families splintered apart by one or more members traveling to Europe in hope of bringing their families safely to join them through family reunification mechanisms. Several years on and these families remain separated, living in limbo, and uncertain of their futures. I learned from them that the decision to cross the sea to Europe was never taken lightly. It was always tortured, always heart-wrenching, and always borne of desperation and fear for the future of their children.

In Sicily, I met survivors of the sea crossing from Libya and Turkey who described to me harrowing journeys on overloaded, unsafe boats. Bodies crammed together, waves towering overhead, night skies so dark you can’t tell where sky ends and sea begins, a relentless fear of capsizing. And always, children who can’t swim, who are hungry, exhausted, and burnt badly from exposure to sun, seawater, and the toxic fuel that collects inside rubber boats.

At a cemetery in Catania, Sicily, there is an area that at first appears to be a wasteland of withered grass, weeds, and trash. It is in fact row after row of unmarked, unkempt graves, beneath which lie the remains of refugees and migrants who perished in the Mediterranean trying to reach Europe. There are no loving tributes chiseled into marble in this cemetery, no groundskeepers, no flowers. On top of Plot 2, PM 3900 01 sits a grimy little ceramic plate, oval-shaped, no bigger than the palm of my hand. On its surface, a light-haired little boy smiles. His face – and the red polo shirt he wears – reminds me, inevitably, of Alan Kurdi.

Although sea arrivals in Europe have dropped dramatically since Alan Kurdi’s death, the public debate around this issue has heightened, and grown ever more divisive. Amidst all this, the memory of Alan’s tragic end has been fading, as has the collective outrage that gripped the world when photos of his dead body went viral. More than 1,500 people, including many children, have died at sea this year alone on journeys similar to that of Alan and his family. Yet the global response is now far more subdued.

Despite all this, I always come away from my visits with UNHCR deeply overcome. Overcome by the power of human resilience, by the deep and inexhaustible well of human courage and decency, overcome by what people will endure to protect their families, look after their children, and secure a measure of dignity.

And I am always encouraged to see the efforts of the many who work to receive and welcome those who make these desperate journeys. I am inspired by those who work tirelessly to expand legal pathways that allow families to remain together, and that make it possible for refugees to travel in safety and dignity. And I applaud all who stand in solidarity with refugees and help them in myriad ways to rebuild their lives. The third anniversary of Alan Kurdi’s death is an opportunity for us all to reflect on how we too can help prevent such future tragedies.

DESPERATE JOURNEYS

Thousands of people continued to try to reach Europe in search of international protection and family reunification in the first seven months of 2018, along with many others traveling to Europe for different reasons including economic and educational opportunities. Between January and July, the number of refugees and migrants entering Europe via Greece, Italy and Spain dropped by 41% compared to last year. New measures targeting irregular migration in the central Mediterranean, including further support for Libyan authorities to prevent sea crossings to Europe, further restrictions on the work of NGOs involved in search and rescue operations, and limited access to Italian ports for refugees and migrants rescued at sea since June, led to fewer arrivals in Italy, but a far higher death rate.[1] Support for the Libyan Coast Guard to build its capacity,[2] including the establishment of a Libyan search and rescue region, has also resulted in increased numbers of people, including those in need of international protection, intercepted or rescued at sea by the Libyan Coast Guard and returned to Libya. Once in Libya, they are detained with no possibility of release by UNHCR except for the purpose of evacuation to a third country. As of the end of August, commercial and NGO vessels[3] conducting rescues in the central Mediterranean Sea continue to face uncertainty over the designation of a safe port for disembarkation in the absence of a collaborative and predictable approach to Mediterranean Sea crossings.[4]

In Greece, in spite of the overcrowded and terribly difficult conditions in reception centres on the islands, arrivals continued including high numbers of family groups, with many likely to be in need of international protection in view of the countries they mainly originate from. In Spain, increased sea arrivals have resulted in the need for increased capacity for reception, while alleged push-backs were recorded at the land border between the Ceuta enclave and Morocco. Similarly, at many other European borders, including in the Balkans, a number of police and border authorities continued to allegedly push back refugees and migrants from inside their territory to a neighbouring country, often denying access to asylum procedures, and in many instances resorting to violence.

So far in 2018 there have been further changes to routes to and through Europe, including in response to border restrictions. Of those who make it to Europe, many report having been subjected to multiple forms of abuse along the route. Many of those crossing the sea from Libya report witnessing deaths including prior to the sea journey. Along land routes including in Europe, more deaths are taking place this year with 74 deaths recorded in the first seven months of 2018 compared to 42 in the same period last year. These deaths occur as refugees and migrants continue to resort to very risky means to cross borders.

Further actions are needed by European States to strengthen access to protection for refugees in Europe, including their access to States’ territory and asylum procedures including the use of accelerated procedures, enhance the quality of reception conditions for those arriving in Europe, strengthen the response to persons with specific needs, in particular unaccompanied and separated children traveling to and through Europe, ensure a consistent and predictable approach to rescue at sea and disembarkation in the Mediterranean, increase access to safe and legal pathways to protection as viable alternatives to dangerous journeys for those who are in need of international protection, and facilitate timely returns, in safety and dignity, of those found not to be in need of international protection or with no compelling humanitarian needs following a fair and efficient procedure.

TOTAL MONTHLY ARRIVALS 2016–2018

PROTECTION RATES IN THE EU+ REGION IN 2017

AND TOP COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN OF ARRIVALS IN GREECE, ITALY AND SPAIN IN 2018

* January to June 2018.

Note: The EU+ region refers to the 28 EU Member States plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland. Based on Eurostat data for 2017. These protection rates are for the listed nationalities regardless of where they entered Europe. International protection includes those granted refugee status or subsidiary protection. It should be noted that humanitarian status is not always granted for protection reasons; depending on national legislation it may also be granted for compassionate or practical reasons such as medical grounds or integration purposes.

INTRODUCTION

The first seven months of 2018 saw refugees and migrants arriving in Europe at lower levels overall than in the previous two years, with increased arrivals in Spain and Greece but significantly lower arrivals in Italy. As with 2017, this year saw further efforts by European authorities to reduce irregular migration without sufficiently increasing access to safe and legal pathways for those in need of international protection.

In the first half of the year, most refugees and migrants arrived in Europe via Greece where some 22,000 arrivals by land and sea were recorded up to the end of June compared to 17,900 in Spain and 16,600 in Italy in the same period. However, by the end of July, Spain had become the primary entry point to Europe with some 27,600 land and sea arrivals compared to 26,000 in Greece (by land and sea) and 18,500 in Italy in the same period. This was largely the result of high numbers of sea arrivals in Spain since June combined with reduced numbers crossing the sea to Greece in the same period.

Along the Central Mediterranean route, the primary entry point to Europe in 2014, 2016, and 2017, in addition to the restrictions imposed in 2017,[5] further changes have taken place over the past months. These changes include Italy refusing to allow the disembarkation of several NGO vessels carrying rescued refugees and migrants since early June. UNHCR commends those European States that have come forward to receive people rescued from the Mediterranean Sea, which has highlighted the benefits of a collaborative approach.

Changes in numbers of people arriving via the three Mediterranean routes[6] also resulted in changes in the primary nationalities arriving in Europe so far this year compared to the same period last year. While the top three nationalities entering Europe in the first seven months of 2017 were Nigerians, Guineans and Ivoirians (mostly via the Central Mediterranean route), as of July 2018, the primary nationalities have been Syrians, Iraqis (both mostly via the Eastern Mediterranean route) and Guineans (mostly via the Western Mediterranean route).[7]

© UNHCR/Chris Melzer

Numeir fled Syria when he was just 15 and travelled through Turkey, Greece and the Balkans, before finally reaching an uncle in Germany. By the time he arrived, in 2015, he was 16 and thousands of miles from his family. For three years he had just one wish:

“I want to share the beauty here with the people who are most important to me in the whole world – my family.”

With UNHCR’s help, Numeir was able to bring his family, who had since fled to Greece, safely to join him in Germany. Read more>

People traveling to Europe continue to do so for different reasons. Some continue to flee armed conflict, insecurity, and human rights violations, while others seek international protection on account of religious, ethnic or political persecution, persecution due to their sexual orientation or gender identity, or to escape different forms of sexual or gender-based violence. Some make these journeys to reunify with family members in Europe while others are seeking employment or education opportunities. Some of the latter have subsequently been granted temporary humanitarian protection in Europe on account of extensive abuses experienced along migration routes to Europe. Eurostat data from the 32 countries[8] in the European Union (EU) + region from 2017 shown in the attached table indicates the varying protection rates for the primary nationalities entering Europe with the majority of some nationalities being granted international protection in Europe in contrast to lower proportions of other nationalities. In the first seven months of 2018, a significantly higher proportion of those arriving in Europe via the Eastern Mediterranean route were likely to be in need of international protection based on their country of origin than those arriving via the Central Mediterranean and Western Mediterranean routes.[9]

The risks involved for refugees and migrants traveling to Europe remain very high. As of the end of July, nearly 1,600 people are known to have died or gone missing in the Mediterranean Sea and along land routes in 2018, excluding those who have died along routes to and through North Africa, such as in the Sahara Desert or Libya. Despite the lower numbers crossing the sea from Libya, a higher proportion of people are dying at sea with one death for every 18 persons who arrived in Europe via the Central Mediterranean route[10] between January and July this year compared to one death for every 42 in the same period in 2017. As of the end of July, nearly 1,100 persons were believed to have died at sea along the Central Mediterranean route in 2018.

A major factor contributing to the increased death rate is the decreased search and rescue capacity off the Libyan coast this year compared to the same period last year. In the first seven months of 2017, NGOs were the primary actors intervening off the Libyan coast. In this period, eight NGOs rescued almost 39,000 refugees and migrants. The presence of NGO vessels and others operating in international waters closer to Libyan territorial waters than at present was also critical in detecting boats in need of rescue.[11] In contrast, in the first seven months of 2018, the Libyan Coast Guard has become the primary actor intervening off the Libyan coast, including sometimes over 70 miles from the shore, with most interventions conducted by two patrol vessels. The number of NGOs operating off the coast on a consistent basis has been reduced to two, meaning more limited capacity to detect and rescue vessels in distress.[12] As a result, rescues (as well as interceptions) have increasingly taken place further from the coast in the first seven months of 2018 compared to the same period last year. The impact of this has been that refugees and migrants are traveling on overcrowded and unsafe vessels for longer periods and over further distances prior to detection and rescue (or interception) with fewer actors to assist in the event of a capsize in international waters.

Along the Western Mediterranean sea route from North Africa to Spain, the number of deaths (318 as of the end of July) increased significantly compared to last year when just 113 deaths were recorded in the same period. In April this year, when over 1,200 people reached Spain by sea, the rate of deaths climbed as high as one death for every 14 arriving. Similarly, 74 deaths of refugees and migrants have been recorded in 2018 as of July along land routes in Europe or at Europe’s borders compared to 42 in the same period last year.

For many, the sea journey is just one of numerous dangers they face along the route from their country of origin to and through Europe, a journey which can take several months or even years. Many people arriving in Europe, especially via the Central Mediterranean route, had not originally planned to go to Europe but experiences or conditions in countries along the route encouraged or forced them to cross.[13] Of those arriving in Europe from Libya, the majority are thought to have experienced violence including torture along the route, mostly in Libya, and many are believed to have witnessed one or more deaths. Additionally, refugees and migrants arriving along this and other routes to Europe have reported being kidnapped for ransom, sold for extortion or forced labour, forced into sexual exploitation, subjected to sexual violence, held against their will without sufficient food and water, beaten by state authorities while attempting to cross borders irregularly, and abandoned in the desert.

Some progress has been recorded in terms of expanding access to safe and legal pathways to protection. As of the end of June, some 13,100 people[14] have been resettled to Europe this year and European States have committed to resettle over 7,200 refugees from certain countries along the Central Mediterranean route as a means of increasing alternatives to dangerous journeys. Almost 1,000 others were granted entry through the “humanitarian corridor” initiatives of Belgium, France and Italy. No figures are yet available for those granted entry on the basis of family reunification but a forthcoming UNHCR report outlines legal and practical obstacles in accessing such procedures for many of those eligible.

Seeking a safe haven

By Leo Dobbs

© UNHCR/Socrates Baltagiannis

THESSALONIKI, Greece – Mahmoud’s eyes moisten when he talks about his home town in northern Syria.

“Going back to Afrin is not an option anymore,”

says the 37-year-old electrician, who fled to Greece with his wife and two sons to escape the military assault on the town and environs earlier this year.

When the bombing started they made their way to the border with Turkey, staying with friends. “We were terrified,” Mahmoud recalls.

His older son, Shivan, aged nine years, was particularly traumatized. “He developed a sort of paralysis because of the terrible things he saw, and that’s why we came to Greece,” Mahmoud explains.

This meant crossing the Evros River, which forms most of the 190-km Greece-Turkey border and has proved deadly to hundreds of people this century, many of them refugees. This year, at least 17 people have drowned trying to cross the river compared to six in all of 2017.

Mahmoud, wife Nisreen and the two boys, Shivan and five-year-old Mustafa, safely navigated the fast-flowing stretch of water in early April and walked for several hours before finding shelter in a church, where they were given food. They spent one day in police detention and six days in the Fylakio Reception and Identification Centre (RIC).

April proved to be a peak in the number of arrivals by the Evros land route, with more than 3,600 people, mostly from Syria, recorded, compared to fewer than 1,500 every other month in 2018. This rise put great strain on the reception facility.

The situation has improved since then, but while people continue to arrive by land and sea, available accommodation on the mainland in Greece is insufficient to house everyone. After being released from the Fylakio RIC, Mahmoud and family headed to Athens, sleeping rough and running out of money. After hearing of possible accommodation in Thessaloniki, they travelled north and ended up at Diavata, a former military facility that has been transformed into one of the government-run open sites.

There they were placed in a container home, together with other Kurdish families from Afrin. “It has become our dream to have our own container,” says Mahmoud. More recent arrivals live in light tents and face overcrowding, tension between groups and worsening conditions.

“We are seeking a safe haven,”

says Mohammad, who also wants an education for the boys and treatment for Shivan.

CHANGING PATTERNS OF MOVEMENT

Since August 2017, and as a result of actions including enhancing the capacity of the Libyan Coast Guard to undertake rescue and interception at sea, the numbers of people reaching Italy by sea from Libya have reduced significantly. While arrival rates to Italy have considerably decreased, in parallel, higher numbers of refugees and migrants arrived in Europe via Spain and Greece. At this point, however, there is no conclusive evidence to demonstrate whether the increased use of the Western Mediterranean route via Morocco is a direct result of the greater restrictions imposed on departures from Libya although some of the same nationalities have been using both routes as was also the case last year.

Along the Eastern Mediterranean route, most arrivals in the first seven months of 2018 continued to be Syrians, Iraqis and Afghans, with many arriving in family groups. In addition, land and sea arrivals in Greece have almost doubled compared to the same period in 2017. In Bulgaria, where a fence covers much of the land border with Turkey, a further reduction of arrivals was witnessed as of the end of July with just under 1,100 refugees and migrants apprehended at entry points with Turkey and Greece and exit points with Serbia and Romania as well as inland compared to over 1,800 in the same period last year.

Of those using other routes from Turkey, whilst over 500 people (almost all Syrians) had crossed by sea to Cyprus from Turkey in the first seven months of 2017, this year fewer than 100 arrived in the same period, although the Turkish Coast Guard rescued or intercepted several hundred others headed that way. This year an increase in Syrians arriving in Cyprus via air after traveling from Lebanon has also been observed.

Further, while almost 2,500 refugees and migrants crossed directly by sea from Turkey to Italy in the first seven months of 2017, this year just over 1,600 refugees and migrants arrived via that route in the same period. And while some 500 people crossed the Black Sea from Turkey to Romania in 2017 from August onwards, so far this year no groups have arrived in Romania this way.

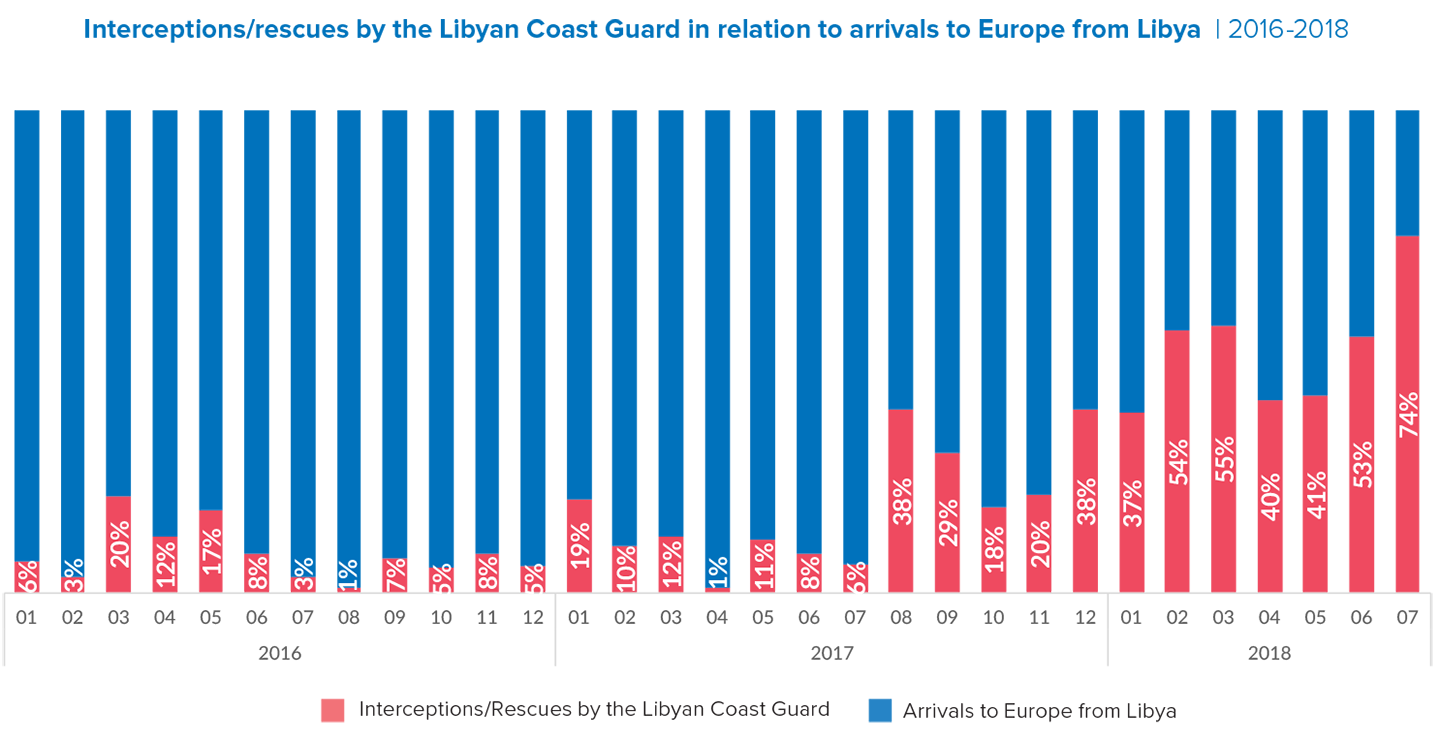

Along the Central Mediterranean route, the limited access to Italian ports since June together with the increased activity of the Libyan Coast Guard, in addition to other measures to reduce departures from the Libyan coast introduced in mid-2017,[15] has impacted the arrival numbers. Whilst the number of refugees and migrants departing the Libyan coast has dropped significantly compared to the first seven months of 2017, the number (as well as proportion) of persons intercepted or rescued at sea by the Libyan Coast Guard and returned to Libya has increased in 2018 (12,600, compared to 8,850 in the first seven months of 2017). Since February 2018, over 40% each month of those known to have departed from the Libyan coast have been rescued or intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard and returned to Libya. In July, that proportion rose to 74%. Since September 2017, higher numbers of people (almost all Tunisians) have been crossing to Italy from Tunisia (over 3,800 in the first seven months of 2018), including small numbers of people from Sub-Saharan Africa (most of whom are not believed to have travelled onwards from Libya).

Search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean Sea help many migrants and refugees find safety in southern Spain after a perilous journey. In the first seven months of 2018, Salvamento Maritimo rescued some 22,000 people. © UNHCR/Rocío González

Arrivals to Spain, mostly by sea, have continued to increase with most crossing from Morocco. June and July saw particularly high numbers crossing the sea. Those making the sea journey do so via several routes, including crossing the Alboran Sea in the western Mediterranean, via the Straits of Gibraltar, via a new route with departures from west of Tangiers, a limited number of crossings from Algeria, as well as those headed to the Canary Islands. In the first seven months of 2018, most arrivals to Spain by land and sea were from Guinea, Morocco, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, and the Syrian Arab Republic. Syrians continued to be the largest group arriving by land, including some new arrivals who had traveled via Sudan, Libya, Algeria and Morocco. Since the start of the year, there have been fewer attempts to cross the fences at the two enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, including due to measures taken by Moroccan authorities to prevent and deter such crossings. However, on 26 July, a group of almost 600 managed to cross the fences to Ceuta.

In the Western Balkans, Bosnia and Herzegovina witnessed a significant increase in refugees and migrants arriving and transiting through the country with over 10,100 arrivals recorded by the end of July this year (compared to under 250 in the first seven months of 2017), although similar numbers have been noted in other countries in the region for some time implying that people at times move back and forth from one country to another in search of alternative routes. Those entering the country have travelled onward irregularly from Greece through Albania and Montenegro or are trying to move onwards from Serbia, including people who were previously waiting to try to enter Hungary via the two ‘transit zones’ where access has been further reduced. Similarly, there have been more refugees and migrants arriving in Serbia this year compared to the same period last year. This includes increased numbers of Iranians flying into Belgrade then travelling onwards irregularly through the region since the start of the year. Another route onwards from Greece that has been used more this year has been by boat to Italy with just over 600 people known to have crossed as of the end of July (compared to 220 in the first seven months of 2017). Several other boats that have attempted to depart from the western coast of Greece have been intercepted or rescued in Greek waters by Greek authorities.

At Italy’s northern borders, some refugees and migrants continue to try to move onwards, and the difficulties in crossing the border with France around the Ventimiglia area have contributed to the emergence of new routes to France through the Alps in the Bardonecchia region.

ACCESS TO TERRITORY AND ASYLUM

The movement of refugees and migrants to Europe has remained the subject of much political interest and debate in Europe since the start of the year despite much lower overall arrivals with further measures introduced to prevent or deter arrivals or reduce onward movement through Europe.[16] UNHCR recognizes the right of every country to protect its borders. However, border control should be protection-sensitive and people in need of international protection should be able to seek asylum. Measures this year to try to further reduce the number of arrivals in Europe, in addition to the limited access to Italian ports for refugees and migrants rescued at sea since June, included further restrictions on the work of NGOs involved in search and rescue off the Libyan coast,[17] and additional support to Libyan authorities to prevent sea crossings to Europe.[18] These are in addition to other existing measures, such as the provisions of the EU-Turkey Statement concerning those crossing the sea from Turkey to Greece.

In the central Mediterranean, several factors have made it harder for people departing from Libya seeking international protection, as well as migrants, to reach Europe.[19] Since August 2017, the Libyan Coast Guard has taken on an enhanced role in operating over a wider area beyond its territorial waters and taken responsibility for intercepting or rescuing a greater number of boats. In June 2018, the establishment of a Libyan Search and Rescue Region was confirmed by the International Maritime Organization. As a result of the enhanced role of Libyan authorities at sea, and despite the far lower numbers of people departing from the Libyan coast between August 2017[20] and July 2018, Libyan authorities have intercepted or rescued 18,400 refugees and migrants between August 2017 and July 2018, compared to 13,300 between August 2016 and July 2017, representing a 38% increase. In the same periods, sea arrivals from Libya to Europe have decreased by 82% (from 172,000 to 30,800). Although additional capacity for rescue at sea is welcomed, UNHCR remains deeply concerned that persons in need of international protection disembarked in Libya are transferred to detention facilities where there is presently no possibility of release, except in the context of evacuation or resettlement to third countries.[21] More than 3,700 people of nationalities that can register with UNHCR in Libya, including from Eritrea, Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, Iraq, the Syrian Arab Republic and the State of Palestine, have been disembarked by the Libyan Coast Guard and transferred to detention in Libya since the start of the year.[22]

In the eastern Mediterranean, of those trying to enter Europe from Turkey, the Turkish Coast Guard had rescued or intercepted some 15,100 refugees and migrants as of the end of July this year compared to 9,400 in the same period in 2017. While over 1,000 Syrians crossed the sea each month to Greece between March and May, in June and July, the number of Syrian arrivals on the Greek islands dropped to 400 and 500, respectively.[23] Those arriving by sea to Greece still face restrictions requiring many to remain on the Greek islands in terrible reception conditions,[24] sometimes for months depending on their category for asylum processing or readmission to Turkey.

Refugees and migrants line up to receive assistance in Una Sana Canton in northwest Bosnia-Herzegovina in August. Some 5,000 people are staying in hard conditions in improvised tent camps and dilapidated dormitory, in the northwestern towns of Bihac and Velika Kladusa. The country currently has only two state governed asylum and refugee reception centres, which have a combined capacity for approximately 400 people, but none of them are not close to these towns in the country northwestern region. The opening of a new reception centre in Una Sana Canton, which currently accommodates 26 mostvulnerable families represents a significant step in improving reception conditions for vulnerable refugees and migrants in the Una Sana Canton. Besides food and accommodation, the residents will have access to medical, legal and psychological aid and will be able to have full access to asylum process. © UNHCR / Vanes Pilav

At the land border between Greece and Turkey, UNHCR continued to receive numerous credible reports of alleged push-backs by Greek authorities, including by detaining persons, giving no opportunity to apply for asylum, and then summarily return them to Turkey via the Evros River, with violence sometimes being used. While States have the right to control their borders, they also have obligations under national, EU and international law to protect asylum-seekers and refugees. UNHCR has received multiple accounts of such incidents since the start of the year referring to summary group returns through the river allegedly affecting several hundred people. Such returns pose several physical and other protection risks to persons affected, who often include children and vulnerable individuals. While far lower numbers are known to have crossed to Bulgaria from Turkey, UNHCR has received information on some push-backs from Bulgaria to Turkey. In both countries, UNHCR continues to address these allegations with the respective authorities.

As refugees and migrants irregularly travelled onwards from Greece and Bulgaria via the Balkans, multiple allegations of push-backs by authorities of governments in the region have been recorded since the start of the year including from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Hungary, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia, and Slovenia. UNHCR and partners in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina[25] received reports of some 2,500 refugees and migrants allegedly pushed back from Croatia with over 1,500 of them reporting denial of access to asylum procedures (including over 100 children), and over 700 people reporting allegations of violence and theft. Since the start of the year, Hungarian authorities reported preventing over 1,100 people from crossing the border and intercepting and returning across the fence over 1,900 people. The police also apprehended almost 280 people in-country who were then given no access to asylum procedures and while some of them were placed in police detention, others were sent to Serbia through the border fence. Since the start of the year, over 150 people have alleged physical violence by Hungarian border authorities during forced removals. Similarly, over 140 people allegedly pushed back from Romania since the start of the year reported the use of violence by Romanian officials. In response to the higher numbers crossing through Bosnia and Herzegovina, several hundred reports of alleged push-backs to Serbia and Montenegro have been received. At least 65 of those who were forcibly moved to Serbia from neighbouring countries since the start of the year have reported having never previously been in Serbia.

Those seeking to enter Hungary via the two ‘transit zones’ at the Serbian border faced further reduced numbers granted entry to the country in February, from 50 persons per week to 10, with just 435 asylum-seekers granted entry in the first seven months of 2018 and just under 250 granted international protection. The reduction of entry numbers increased the average stay in Serbia from 11 months up to 18 months, and is understood to have contributed to more people trying to move on irregularly from Serbia rather than waiting for such a lengthy period to enter Hungary legally. In addition to the mandatory automatic detention for asylum-seekers introduced by Hungary in March 2017, in June, Hungarian authorities introduced new legislation restricting the ability of NGOs and individuals to support asylum-seekers and refugees. In May, UNHCR had called for Hungarian authorities to withdraw the draft law.[26] However, the Act amending certain laws relating to measures to combat unlawful immigration entered into force on 1 July introducing, among other restrictive measures, a new inadmissibility ground,[27] which resulted in an extended admissibility examination for all new arrivals.

At Spain’s land borders with Morocco, further push-backs have allegedly occurred.[28] On 26 July, some 800 people tried to enter Ceuta via the fence with almost 600 succeeding. Video footage of the incident appears to show authorities summarily returning some individuals through gates in the fences from Spain to Morocco.[29] UNHCR continues to monitor access to asylum procedures at Spain’s land borders. With higher numbers arriving by sea in Spain, reception capacity in some disembarkation sites has initially been outpaced. By way of response, the authorities opened a Temporary Assistance Centre in Algeciras port with a view to facilitate the initial registration and processing of all arrivals reaching Spain through the Straits of Gibraltar area. Authorities also opened Centres for Assistance, Stabilization and Diversion to provide temporary accommodation and assistance to those migrants and refugees whose police formalities are concluded, and refer them to the appropriate processes (including asylum procedures) and services.

Lastly, as some tried to move on from Italy to France, French authorities are reported to have pushed back a number of people, including asylum-seekers and unaccompanied children, without following due process.

Forced to cross the Aegean in a bath-sized dinghy

By Despoina Anagnostou, ed. Leo Dobbs

©UNHCR/D. Anagnostou

SAMOS ISLAND, Greece – When Mohammad put his money – and his life – in the hands of smugglers, he expected to be taken to the Greek islands in a seaworthy craft that would ferry him safely and quickly across the sea from Turkey.

As a fisherman, the 39-year-old knew there was always a risk in crossing the open sea, especially at night, but he was desperate to reach Greece after fleeing his native Iran, where he faced religious persecution and feared for his life.

“I had no choice, there was no way back for me,” he said, adding: “The last time I was in touch with my wife, I told her we might never talk again.” His prediction nearly came true; in the waters between Turkey and Greece, he spent hours desperately trying to keep afloat before rescue came.

His journey began earlier this year in Iran when, believing he faced a real threat of execution, Mohammad made a sudden decision to flee, leaving behind his wife and two children. He lacked documents and money and was always hungry. “I picked fruit from trees and looked in garbage cans for leftovers.”

It took him about a month to walk across Turkey to the port of Kusadasi, where he met the smugglers. After relatives wired him money, the smugglers promised to take Mohammad to Greek waters and said it was only a short distance to Samos.

When they got to the shore, Mohammad was excited. “I was so happy, I could see the lights [on Samos], but I hadn’t realized how far the Greek coast was.” He was in for another surprise. When the smugglers’ boat was only 500 metres from the Turkish shore, he was told that he must continue on his own.

Mohammad gingerly boarded a much smaller inflatable dinghy that was barely bigger than a bath. It soon began taking on water and leaking air. He clung to the half-inflated dinghy, battling to keep above water and trying to paddle.

“If I wasn’t such a good swimmer I couldn’t have made it,” he said. “There are many dangers in the sea, including getting cramp. Even an Olympic swimming champion might drown.”

After more than five hours, when Mohammad was beginning to fear he might not make it, he spotted a vessel flying a Greek flag. “I was sure that I had made it to Greek waters. I didn’t have any energy left but I knew it was now or never. I let go of the inflatable and swam towards the vessel.”

It turned out to be a Frontex patrol vessel. The German crew gave him blankets and water and took him to Samos where he is now living in the Vathy Reception and Identification Centre. Despite being in Greece, he still worries about his safety and he also suffers from pain in his feet following his long journey.

But now he faces new problems. These include the overcrowding and poor conditions in Vathy, which has a capacity for 700, but currently houses more than 2,800. He lives in a hot, stuffy tent, which he shares with six other people.

Mohammad thinks often about his family, but has not tried to contact them because he fears getting them into trouble.

“Without them I feel like a person in a coma in intensive care, where somebody came and unplugged the cables.”

RISKS TO REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS

The journey to and through Europe remains highly dangerous for many. Risks may include the dangers associated with the terrain, such as crossing the desert and sea, or the journeys across rivers and mountains, especially during winter; dangers due to smugglers, some of whom force refugees and migrants into situations of trafficking; and risks due to mistreatment by state authorities, including in Europe, in the context of border control procedures along the route.

In the first seven months of 2018, over 1,500 refugees and migrants are believed to have died at sea, most of them while attempting to cross the sea from Libya. Along the Central Mediterranean route, so far this year there have been ten incidents in which 50 or more people died in a single incident at sea, most after departing from Libya.[30] Along land routes at Europe’s borders and across Europe, at least 74 refugees and migrants are known to have died since the start of the year while traveling to or crossing a border compared to 42 reported deaths in the same period last year.

Many of those crossing to Europe from Libya have already experienced horrific abuses and witnessed at least one death. New arrivals to Italy this year have frequently reported being sold by one armed group to another, being tortured as part of demands for ransom, being forced to pay sums of several thousand dollars, sometimes on multiple occasions, to secure their release, being subjected to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), and being held without sufficient food or water by armed groups for sometimes one year or more. UNHCR and other observers have at times reported the severely malnourished appearance of groups arriving from Libya, particularly Eritreans, at disembarkation in Italy.[31]

Results from a forthcoming report on UNHCR’s profiling of Eritrean, Guinean and Sudanese arrivals in Italy in 2017 indicated that 75% of the over 900 people interviewed[32] had experienced some form of abuse on the routes leading to Libya. Although not included in the profiling questionnaire, 44% of those interviewed voluntarily reported that they had witnessed one or more deaths during their journey.[33] Results of the profiling showed that of those who had traveled through Libya:

- 64% reported physical abuse, violence or torture;

- 45% reported being subjected to deprivation of food, and 41% to deprivation of water;

- 30% reported having been subjected to exploitative labour practices;

- 21% reported experiencing extortion or corruption;

- 11% reported being shot or threatened with shooting; and

- 3% reported being subjected to sexual abuse or exploitation, including 7% of women and 2% of men.

While some women and men did report experiencing sexual violence, the actual number of survivors is thought to be far higher as sexual violence is typically underreported in such profiling exercises.[34]

In addition to the abuses some experience while traveling to Italy, some endure further hardships during attempts to move on irregularly from Italy. In the winter months, rescuers assisted many people trying to cross irregularly through the Alps to France without adequate clothing or supplies. Since the start of the year, at least eight people are known to have died around Italy’s northern borders, including five at the Italy-France border. Of these, three deaths occurred along the new route in the Bardonecchia area.

Desperate journeys leave indelible marks on young refugees arriving in Europe

By Marco Rotunno in Sicily, Italy

© UNHCR/Marco Rotunno

SICILY, Italy – Yohannes, 17, experienced extreme suffering during his two-year long journey to Italy, including abduction, torture, and severe food deprivation. When he was disembarked in Pozzallo, Sicily in July 2018 along with the other 450 mostly Eritreans rescued from a wooden boat in the Mediterranean Sea, he weighed just 39kg, almost 20kg below the minimum healthy weight for his height.

As a result, Yohannes was sent directly to hospital. The illness he had contracted in a traffickers’ warehouse in Libya was potentially curable but had never been treated. “There were simply no medicines,” he recalls. “Once, a pregnant lady was about to give birth. We screamed, we knocked on the walls but nobody came to help and she gave birth in the big room.”

Amongst those disembarking, Yohannes was not alone in being significantly underweight. Doctors present at the dock noted that around 90 percent of those rescued were to some degree affected by malnourishment.

“Two years ago, I was not like this,” Yohannes tells UNHCR, recounting how he left home alone when he was 15. “My weight was normal. I have changed profoundly since I fled home.” At the start of his journey, Yohannes travelled with some people from his village but they soon separated and he continued alone.

As Yohannes and the group he was being transported to Libya with crossed the desert from Sudan, they were attacked by armed men working for another trafficker. “In that moment I seriously feared for my life,” he says. “Two armed groups started shooting at each other, and we were caught up in the middle.” Yohannes and the group were then abducted by the armed men who held them captive and demanded a ransom. “I felt as if I was a commodity,” he says. “I found myself in a state of limbo where I couldn’t go forward or backwards. I only hoped to stay alive.”

During his time in captivity, Yohannes was held in large overcrowded rooms with hundreds of others. There was not enough food to go around. “Once a day, we would get plain pasta in big pots. We had to eat from the pots in groups of ten,” he recalls. “They would beat us for any reason, even if we’d dare to stare at them. They would use sticks or any object available in the room.”

Now safe in Italy, Yohannes has been staying in a centre for unaccompanied children along with other Eritrean boys and taking medicines and vitamins prescribed by doctors to recover his health. He has also been able to resume contact with his parents. “The first time we could speak with our parents was when we arrived to Italy. We were so overwhelmed that we could not speak, but just screamed with happiness.”

Yohannes is now thinking about the future.

“I started learning Italian. Beside that, I can finally focus on my new life. I would love to work as a professional driver.”

Along the Eastern Mediterranean route from Turkey, at least 99 people are known to have died at sea so far this year in just five incidents, more than double the 38 reported dead in the same period last year. The reported deaths this year include 44 persons believed dead when their boat capsized en route to Cyprus in July. So far this year, 56 people have died while trying to cross by sea to Cyprus, a route on which no deaths have been reported over the past few years. With only 73 sea arrivals recorded to Cyprus as of the end of July, the rate of deaths in relation to those who have crossed is extremely high.

As more people have crossed the land border between Greece and Turkey this year than in previous years, the number of deaths has also risen with at least 33 people known to have died along the route since the start of the year. Of these, 17 people, including young children, have drowned in the Evros River in at least ten different incidents, and 13 have been killed in vehicle or train accidents in five incidents.

While the scale of abuses affecting persons traveling along the Eastern Mediterranean route is understood to be lower than along the Central Mediterranean route, UNHCR has still received reports of a number of incidents involving abuses by smugglers, including some cases of persons being held against their will for extortion. In addition, despite underreporting of SGBV, since the start of the year UNHCR in Greece has received reports of at least 140 incidents that occurred along the route between the country of origin and Greece.

Reports of violence and mistreatment along the route for those arriving in Spain are relatively common amongst people encountered by UNHCR. For example, in a UNHCR profiling exercise involving over 1,000 people who arrived in Spain in 2017, 39% reported experiencing physical abuse or violence along the route, including multiple reports of robbery and kidnapping for ransom. Amongst the incidents reported were many accounts of kidnapping for ransom, forced labour, and physical violence in locations between northern Mali and southern Algeria. UNHCR has also received a number of testimonies from new arrivals in Spain this year regarding SGBV, including women and men raped along the route and some women forced into sexual exploitation on account of their vulnerable situation. In addition, UNHCR has received testimonies from some people who appear to be victims of trafficking.

Refugees and migrants interviewed in the Balkans by UNHCR and partners have reported sometimes being held by smugglers without sufficient food as part of demands for additional payments. Others have been robbed along the way by local gangs, and many women and girls, as well as some men and boys are understood to have suffered sexual violence along the route. Since the start of the year, at least 26 people are known to have died in 22 separate incidents while traveling irregularly through the Balkans. Of these, 12 have drowned with most incidents taking place at the Croatia-Slovenia border.

Together again

By Mirjana Milenkovski

© UNHCR/Marco Rotunno

BELGRADE, SERBIA – Shafiq decided to flee Afghanistan when a man showed up at his workshop and threatened to kill them all if the family did not give him their daughter, who was only thirteen, to repay a family debt. The family travelled to Turkey then crossed the sea to Greece before trying to travel onwards. It was then that the family began yet another ordeal as they were separated while trying to cross the border.

The family of five was part of a group crammed into two vans by smugglers as they traveled at night to Greece’s northern border with the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia in July this year. They were almost at the border when a police patrol stopped the vans and everyone ran into the nearby woods. In the confusion, the family’s older children, Mozhdah, 13, and Mangal, 8, thought they were running behind their parents, only to later realise they had lost sight of them. Scared and disoriented, the children joined another Afghan family and crossed the border before making their way to Serbia.

For nearly two weeks, Shafiq and his wife Ghazal knew nothing about the whereabouts of their children. UNHCR protection monitors came across Mozhdah and Mangal, exhausted and terrified, in the north Serbian town of Subotica, close to the border with Hungary. The children were assisted with the appointment of a legal guardian and were referred to one of the four facilities for accommodation of unaccompanied and separated children in Serbia.

A few days later, Shafiq and Ghazal and the youngest child arrived at a refugee aid point in Belgrade where they told a UNHCR partner what had happened. “When we saw their personal information and that of their children, we quickly realized it was the children encountered in Subotica by other partners in the UNHCR network,” said a UNHCR Child Protection Assistant. UNHCR and partners, in cooperation with Serbian authorities took steps to reunify the family.

For Ghazal, the memory still hurts. “We knew nothing of them for nearly two weeks,” she recalls, “I felt I was drowning in despair.” “It’s all right,” Shafiq assures her, “We are all back together now.”

The family was accommodated in an Asylum Centre near Belgrade where Mozhdah and Mangal started to recuperate from the shock of separation and attended language and art lessons.

* Names changed for protection reasons

CHILDREN ON THE MOVE

More than 3,500 unaccompanied and separated children (UASC) have arrived in Europe via the three Mediterranean routes in the first seven months of 2018, compared to over 13,300 in the same period last year. Almost 2,900 unaccompanied children arrived in Italy as a result of sea journeys, primarily from Libya and Tunisia. The majority of children so far were from Eritrea, Tunisia, and Sudan.[35]

Previous reports have shown that children traveling through Libya have left their home for different reasons, often without originally intending to travel to Europe.[36] Many are subjected to similar abuses as adults.[37] In addition, children, both accompanied and unaccompanied, who are intercepted or rescued off the Libyan coast by the Libyan Coast Guard are also transferred to detention facilities upon disembarkation in Libya. As of the end of July 2018, nearly 1,200 children have been transferred to detention in Libya. While UNHCR has been able to evacuate a number of unaccompanied and separated children from detention in Libya to Niger, finding durable solutions for them remains to be challenging.[38]

As in 2017, many unaccompanied and separated children are amongst those who try to move irregularly from Italy. Of those trying to cross to France in the Ventimiglia area, many are understood to be from Eritrea, Sudan and Afghanistan.[39] NGOs have consistently reported summary returns of unaccompanied children from France.[40]

Along the Eastern Mediterranean route, some 600 unaccompanied and separated children, mostly from the Syrian Arab Republic and Afghanistan, were on the Greek islands as of mid-July with an estimated additional 2,900 unaccompanied and separated children elsewhere in Greece. Of those on the islands, on Lesvos, around 80 unaccompanied children are accommodated with adults and families in a crowded warehouse tent without adequate access to services and designated safe spaces. On Chios and Samos, unaccompanied children are sometimes placed with single women or families because of the overcrowded and terrible conditions. Access to health care services for the children remains a concern, including to mental health support.

The vast majority of unaccompanied children in Greece are boys (94%) and almost 250 (7%) unaccompanied and separated children are under the age of 14. Most come from Pakistan (36%), Afghanistan (29%) and the Syrian Arab Republic (14%). The number of children is greater than the number of shelter places available and as of mid-July, some 2,500 unaccompanied and separated children were on the waiting list for shelter. Of those waiting, more than 500 were reported to be homeless while the whereabouts of some 300 was unknown.[41]

In the Balkans, UNHCR has observed the arrival of a number of unaccompanied and separated children, mostly from Pakistan and Afghanistan, with some 800 unaccompanied and separated children recorded in Serbia in the first half of the year. UNHCR Serbia, in cooperation with authorities and partners continued a successful guardianship pilot project and supported adequate accommodation and care for children in three government facilities. Children trying to cross borders irregularly have frequently been amongst those alleging push-backs, sometimes involving violence, as well as denial of access to asylum procedures, and sometimes theft.

© UNHCR/Louise Donovan

Eritrean women who survived abuse in Libya resettled to Europe

“I can’t think about the past anymore, I need to think about the new future I have ahead of me.”

Rahua*, 22, fled Eritrea in 2015 and suffered physical and psychological abuse at the hands of smugglers. Rahua was held with two other Eritrean women for over a year. The young women are among thousands of vulnerable refugees being evacuated out of detention centres in Libya by the UN Refugee Agency. They have since been resettled to Finland.

SAFE AND LEGAL PATHWAYS

While there have been important increases in Europe’s contribution to providing access to safe and legal pathways for people in need of international protection, which has helped to partially compensate for a reduction in such pathways, including resettlement places, in other regions, enhanced efforts are still required which could include expanded numbers of resettlement spaces and removing the multiple obstacles inhibiting access to family reunification for those who are eligible.

In the first six months of 2018, some 13,133 refugees were resettled to Europe,[42] mostly to Sweden (3,050), the United Kingdom (2,948), France (2,350) and Germany (1,708).

A positive development this year has been the increase in the numbers of people resettled to Europe from countries along the Central Mediterranean route, including the resettlement of those evacuated from Libya to Niger through the Emergency Transit Mechanism (ETM). As of 6 August, 367 refugees have been resettled from Niger to Europe, with the largest groups being resettled by France and Switzerland. As of 6 August, 1,858 refugees have been evacuated from Libya since the initiative started in early November 2017, with over 1,500 evacuated to Niger for further processing, 312 evacuated directly to Italy, and 10 to the Emergency Transit Centre in Romania. At present, UNHCR is only able to secure release from detention in Libya for the purpose of evacuation to third countries.[43] This includes those detained following interception or rescue at sea and subsequent disembarkation in Libya.[44]

As of August, European States have pledged almost 2,800 places for resettlement out of Niger, both for those evacuated from Libya and refugees already in Niger, as well as a further 4,440 places for refugees to be resettled from some of the 15 priority countries along the Central Mediterranean route in response to UNHCR’s call for 40,000 additional resettlement places from along the route issued in September last year.[45] European States have also pledged 440 places for refugees to be resettled directly from Libya.[46]

In addition to those resettled to Europe, further arrivals took place via the “humanitarian corridors” initiatives to Belgium, France, and Italy, which is the result of formal cooperation between some faith-based organizations and the respective governments in these States. This included 750 Syrians, Ethiopians, Eritreans and some refugees of other nationalities arriving in Italy since the start of the year. In Belgium, 72 Syrians from Lebanon and Turkey have arrived on humanitarian visas since late 2017, while in France, 160 Syrians have arrived from Lebanon since the start of the programme in 2017. In Germany, a limited number of arrivals also took place via the Private Sponsorship Programme that still operates in five states.

Family reunification remains an important mechanism for safe and legal entry to Europe, although many of those eligible face barriers to accessing the procedure. UNHCR continues to encounter refugees traveling irregularly to Europe on account of lack of access to family reunification mechanisms, despite being eligible. In a positive development, the European Court of Justice ruled in April that unaccompanied children who reach the age of majority during the course of their asylum procedures still retain their right to family reunification,[47] thus responding to an issue which saw some children denied the right to reunify with their parents or other family members as a result of turning 18 prior to the completion of their asylum or family reunification applications. In another significant development, Germany ended its suspension since March 2016 of family reunification for beneficiaries of subsidiary protection at the start of August. Visas will only be issued for up to 1,000 persons per month and it is hoped that these numbers can be progressively increased. Many Syrians in Germany are beneficiaries of subsidiary protection. UNHCR has called for families with young children to be prioritized and for the length of stay in Germany to be considered.[48]

For those who had arrived in Greece or Italy by 26 September 2017 and were eligible for relocation through the EU’s Emergency Relocation Mechanism, a small number of relocations took place in 2018 as the scheme came to an end. As of early July, 22,000 asylum-seekers had been relocated from Greece[49] (33% of the originally foreseen total) and 12,700 from Italy (32% of the originally foreseen total).[50]

Of those who arrived in Greece and had family members elsewhere in the EU, in the first half of the year requests were sent on behalf of some 2,300 people hoping to legally reunify in accordance with the Dublin III Regulation.

Rebuilding life in Spain after a harrowing journey

© Karpov/SOS MEDITERANEE

For many people who have fled from war, the sound of a helicopter’s propellers can trigger a post-traumatic stress disorder reaction and make them want to run and hide. But for Ayman*, the sound is a welcome one, associated with rescue and the end of his ordeal after two days drifting in the Mediterranean Sea.

The 18-year-old from Sudan was among those rescued by the NGO vessel Aquarius on the night of 9 June. Their boat had set sail from Libya, packed with over 100 people. After two days, the boat was almost fully deflated before they were spotted by helicopters coordinated by the Italian authorities. “We had no life-jackets and people were drowning,” Ayman recalls.

“I helped some women to stay afloat but I lost my strength and thought I would die.”

The rescue should have marked the end of an ordeal that had seen Ayman flee insecurity in the town in Sudan where he lived with his parents and siblings, only to face more horrors in Libya. “I have nightmares every day,” he tells staff at the Reception Centre in Madrid where he now lives. “I hear the voices of my friends, their cries while being tortured and the snapping noise of a shot in the head.” Of a group of seven friends, Ayman was the only one to escape from where they were being held captive by an armed group in Libya. “My parent worried about me all the time,” he says. “My brother had died in the Mediterranean, but I’m alive.”

Once aboard the Aquarius, Ayman and others still faced further delays in reaching safety after the vessel was denied disembarkation permission for the over 600 rescued people in Italy and Malta but subsequently allowed to dock in Valencia on 17 June, over a week after the rescue. Since arriving in Spain, Ayman has applied for asylum and now receives support from a multi-functional team at the Refugee Reception Centre to help him become familiar with life in Spain and to overcome the harrowing experiences of his journey. At present, Ayman enjoys exploring the Madrid with his roommate and has started feeling more secure. “I want to work as a carpenter, I’m good at woodwork,” he tells UNHCR, as he looks to the future away from the violence of his past.

(*) name has been changed for protection reasons.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

As part of efforts to strengthen protection across the region, UNHCR continues to call on European States to:

- Ensure access to territory for people seeking international protection, implement protection-sensitive border practices that enable border officials to identify people with international protection needs; and grant access to swift and efficient registration and asylum procedures, including the use of accelerated procedures;

- Throughout the Mediterranean Basin, develop a regional and collaborative approach to make disembarkation of people rescued at sea more predictable and manageable and save lives as outlined in the joint proposal by UNHCR and IOM;[51]

- Strengthen protection mechanisms for children including by integrating unaccompanied and separated asylum-seeking children within national child protection systems, ensuring children are not detained for immigration purposes, and enhancing access to psycho-social support;

- Continue to enhance efforts to tackle trafficking along the three Mediterranean routes as well as within Europe, including related to people trafficked for sexual exploitation in Europe;

- Enhance access to safe and legal pathways for those in need of international protection, including by increasing resettlement commitments and removing obstacles to family reunification;

- Strengthen the quality of reception facilities and conditions, ensure fair and efficient asylum procedures, and enhance referral and access to support services for those with specific needs; and facilitate timely returns, in safety and dignity, of those found not to be in need of international protection or with no compelling humanitarian needs following a fair and efficient procedure; and

- Provide support to increase the availability of effective protection in countries of first asylum and countries of transit.[52]

Sources

[1] The death rate here refers to the number of deaths in relation to the number of arrivals by sea in Europe via the Central Mediterranean route.

[2] European Council, European Council conclusions, 28 June 2018, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/06/29/20180628-euco-conclusions-final/; European Commission , 4 July 2017, http://europa.eu/rapid/%20press-release_IP-17-1882_en.htm; DW, Italy gives Libya ships, equipment as more migrants reported lost, 3 July 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/italy-gives-libya-ships-equipment-as-more-migrants-reported-lost/a-44498708. Further Italian support has included maintenance of Libyan vessels as well other support provided by the crew of Italian Navy vessels docked in Tripoli, see Italian Embassy in Libya, 28 March 2018, https://twitter.com/italyinlibya/status/979027386971901954.

[3] In addition, in August 2018, over 170 persons rescued after departing from Libya spent several days on the Italian Coast Guard vessel Diciotti anchored off Lampedusa and then in port in Catania before they were granted permission for disembarkation.

[4] In response to limited access to Italian ports for the disembarkation of those rescued at sea, UNHCR and IOM have developed a proposal for a collaborative regional approach to disembarkation and processing of persons rescued at sea, see UNHCR and IOM, Proposal for a regional cooperative arrangement ensuring predictable disembarkation and subsequent processing of persons rescued-at-sea, 27 June 2018, http://www.unhcr.org/5b35e60f4. Since June, some additional coastal states have offered disembarkation, including following pledges from European States to accept the transfer of some of those rescued.

[5] UNHCR, Desperate Journeys: January 2017 – March 2018, April 2018, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/63039; UNHCR, Desperate Journeys: January – September 2017, October 2017, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/60865.

[6] The Central Mediterranean route runs from North Africa to Italy, the Eastern Mediterranean route includes land and sea arrivals to Greece, along with arrivals to Bulgaria and Cyprus; and the Western Mediterranean route runs from North Africa to Spain.

[7] As illustrated in the graph on page 10, the protection rates for different nationalities along the three routes varies significantly.

[8] The 28 EU Member States along with Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland.

[9] However, a high proportion of a small number of nationalities using the Central Mediterranean and Western Mediterranean routes may still be in need of international protection as illustrated in the chart on page 8.

[10] This includes persons arriving mostly in Italy after departing from Libya, Tunisia, Turkey, Greece and Algeria. The rate of deaths for those crossing from Libya to Europe in the first seven months of 2018 was even higher with one death for every 14 persons who reached Europe compared to one death for every 40 in the same period in 2017.

[11] The Italian Coast Guard reported that in 2017, over 60% of rescues were the result of the vessel being spotted at sea rather than rescue authorities being alerted for example by a distress call. Of the boats in need of rescue spotted at sea, 41% were spotted by the crew of NGO vessels. See Italian Coast Guard, Annual report – 2017, http://www.guardiacostiera.gov.it/attivita/Documents/attivita-sar-immigrazione-2017/Rapporto_annuale_2017_ITA.pdf.

[12] Despite this, NGOs were still responsible for the largest proportion of those rescued at sea and subsequently disembarked in Italy in the first six months of 2018.

[13] World Bank, Asylum seekers in the European Union, June 2018, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/832501530296269142/pdf/127818-V1-WP-P160648-PUBLIC-Disclosed-7-2-2018.pdf; UNICEF and REACH, Children on the move in Italy and Greece, June 2017, https://goo.gl/XnJ7hV. Research, as well as information from new arrivals in Italy collected by UNHCR, also indicates that some of those who ultimately crossed the sea from Libya were made to do so against their will, including by former employers instead of providing payment. See for example, V. Squire, A. Dimitriadi, N. Perkowski, M.Pisani, D. Stevens, N. Vaughan-Williams, Crossing the Mediterranean Sea by Boat: Mapping and Documenting Migratory Journeys and Experiences, Final Project Report, 4 May 2017, https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/research/researchcentres/irs/crossingthemed/ctm_final_report_4may2017.pdf.

[14] See UNHCR, Resettlement Data Finder, http://rsq.unhcr.org/. These figures are tentative and subject to change.

[15] As noted in a previous version of Desperate Journeys, these included measures outlined in the European Commission’s Action Plan of July 2017 as well as engagement by Italian authorities with Libyan counterparts. See UNHCR, Desperate Journeys: January – September 2017, October 2017, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/60865.

[16] In addition to measures to prevent or deter arrivals, other efforts have been aimed at addressing root causes of migration, trying to strengthen access to protection in some key countries of transit, as well as tackle smuggling and trafficking practices. See, for example, European Commission, Protecting and supporting migrants and refugees: new actions worth €467 million under the EU Trust Fund for Africa, 29 May 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/news-and-events/protecting-and-supporting-migrants-and-refugees-new-actions-worth-eu467-million_en.

[17] Reuters, Italy court releases migrant rescue ship seized last month, 16 April 2018, https://af.reuters.com/article/africaTech/idAFL8N1RT4FQ; Malta Independent, MV Lifeline captain charged with entering Maltese waters on unlicensed vessel, bail given, 2 July 2018, http://www.independent.com.mt/articles/2018-07-02/local-news/MV-Lifeline-captain-arrives-in-court-for-hearing-6736192797; Sea-Watch, Sea-Watch hindered from leaving port while people drown at sea, 2 July 2018, https://sea-watch.org/en/321/; Malta Today, Sea Watch migrant rescue plane blocked from flying by Maltese authorities, 4 July 2018, https://www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/national/87984/sea_watch_migrant_rescue_plane_blocked_from_flying_by_maltese_authorities#.W17F49IzY2w.

[18] European Council, European Council conclusions, 28 June 2018, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/06/29/20180628-euco-conclusions-final/.

[19] The Local, Migrant rescued at sea dies hours after arriving in Italy, 14 March 2018, https://www.thelocal.it/20180314/eritrean-migrant-segen-rescued-mediterranean-starved-death-malnutrion-italy-sicily; InfoMigrants, Stories of migrants that landed on Lampedusa at weekend, 17 July 2018, http://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/10675/stories-of-migrants-that-landed-on-lampedusa-at-weekend?ref=tw.

[20] As outlined in a previous version of this report, since August 2017 there was substantial decrease in the numbers crossing from Libya to Italy with the Libyan Coast Guard taking on an increased role too. See UNHCR, Desperate Journeys: January – September 2017, October 2017, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/60865.

[21] On 24 August, UNHCR Libya noted, “UNHCR is gravely concerned about the worsening conditions for refugees and asylum-seekers detained in Libya. The situation is being compounded further by the limited prospects for solutions to their situation. In recent weeks, UNHCR has witnessed a critical worsening in conditions in detention centres, due to the increasing overcrowding and lack of basic living standards. As a consequence, riots and hunger strikes by refugees inside detention centres are taking place, demanding a resolution to their bleak living conditions…UNHCR estimates that more than 8,000 refugees and migrants are detained in the country. More than 4,500 are considered to be of concern to UNHCR.” UNHCR, UNHCR Flash Update – Libya – 17-24 August 2018, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/country/lby.

[22] UNHCR and the Libyan Ministry of Interior are committed to opening a Gathering and Departure Facility, which would provide an alternative to detention for persons of concern to UNHCR while their cases are processed for evacuations or direct resettlement to third countries.

[23] Reasons for the reduction in numbers of Syrians are understood to include increased controls in the west of Turkey around key departure points as well as at inland locations.

[24] This is in accordance with the EU-Turkey Statement, introduced to reduce the numbers crossing to Greece by sea.

[25] See also The Guardian, Refugees crossing from Bosnia ‘beaten and robbed by Croatian police’, 15 August 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/15/refugees-crossing-from-bosnia-beaten-and-robbed-by-croatian-police.

[26] UNHCR, UNHCR urges Hungary to withdraw draft law impacting refugees, 29 May 2018, http://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2018/5/5b0d71684/unhcr-urges-hungary-withdraw-draft-law-impacting-refugees.html.

[27] See Section 51 (2) f) of Act LXXX of 2007 on Asylum.

[28] The European Court of Human Rights ruled against the collective expulsion of persons who had entered Spain via the fences in October 2017. Following the Chamber judgment, in December 2017 the Spanish government requested for the case to be referred to the Grand Chamber of the Court, which was accepted in January 2018, and the hearing is to take place in September 2018.

[29] El Faro de Ceuta, Cizallas, cal viva y bolas de heces para conseguir una entrada masiva por la valla de Ceuta, 26 July 2018, https://elfarodeceuta.es/cientos-inmigrantes-intentan-entrada-valla-ceuta-meses-bloqueo/.

[30] Of these, seven have taken place since the start of June.

[31] The Local, Migrant rescued at sea dies hours after arriving in Italy, 14 March 2018, https://www.thelocal.it/20180314/eritrean-migrant-segen-rescued-mediterranean-starved-death-malnutrion-italy-sicily; InfoMigrants, Stories of migrants that landed on Lampedusa at weekend, 17 July 2018, http://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/10675/stories-of-migrants-that-landed-on-lampedusa-at-weekend?ref=tw.

[32] Of the sample, 41% were Eritreans and another 41% Guineans with 18% Sudanese. Only 10% of those interviewed were women with a higher proportion amongst Eritreans (23%).

[33] As the profiling did not specifically ask a direct question on witnessing deaths, the actual proportion may have been even higher.

[34] For example, a World Bank report from June 2018 based on surveys and interviews with asylum-seekers in Italy and Greece noted that from qualitative interviews, it appears that sexual violence affected almost all the women who reached Italy. See World Bank, Asylum seekers in the European Union, June 2018, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/832501530296269142/pdf/127818-V1-WP-P160648-PUBLIC-Disclosed-7-2-2018.pdf.

[35] UNHCR, Italy – Unaccompanied and Separated Children (UASC) Dashboard, July 2018, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/65086.

[36] UNICEF and REACH, Children on the move in Italy and Greece, June 2017, https://goo.gl/XnJ7hV.

[37] As noted in the previous report, IOM surveys of over 4,000 people in Italy of which 725 were children, most of whom had traveled from North Africa, between February and August 2017, showed that 77% of children reported being held against their will by groups other than government authorities, mostly due to kidnap for ransom or detention by armed groups and mostly in Libya (91%); and 88% of children between 14 and 17 reported experiencing physical violence, primarily in Libya (82%). See IOM, Flow monitoring surveys: The human trafficking and other exploitative practices indication survey, November 2017, https://goo.gl/gm6og9.

[38] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/01/refugees-niger-africa-eu-summit-border-policy-migrant-children

[39] Oxfam, Nowhere but out, June 2018, https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620493/bp-nowhere-but-out-refugees-migrants-ventimiglia-150618-en.pdf;jsessionid=B65FCD97198513F4FE074DDB18E0E650?sequence=1.

[40] Oxfam, Nowhere but out, June 2018; INTERSOS, Unaccompanied and separated children along Italy’s northern borders, February 2018, https://goo.gl/Kpv58s.

[41] EKKA, Situation update: Unaccompanied children in Greece, 15 July 2018, https://reliefweb.int/report/greece/situation-update-unaccompanied-children-uac-greece-15-july-2018.

[42] Figures subject to change.

[43] IOM is also able to secure release from detention for those who opt for voluntary repatriation.

[44] The Emergency Transit Mechanism in Niger at present provides places for a maximum of 1,000 refugees at a time. This means that some of those evacuated to Niger need to be resettled before UNHCR is able to evacuate more refugees from Libya.

[45] In total as of July, nearly 24,500 resettlement places by all States have been pledged for resettlement from the 15 priority countries along the Central Mediterranean route. UNHCR, Central Mediterranean situation: UNHCR calls for an additional 40,000 resettlement places, 11 September 2017, http://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2017/9/59b6a5134/central-mediterranean-situation-unhcr-calls-additional-40000-resettlement.html.

[46] Out of a total of 1,090 resettlement places pledged by all States.

[47] See Court of Justice of the European Union, Judgment in Case C-550/16: A and S v Staatssecretaris van Veiligheid en Justitie, 12 April 2018, https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2018-04/cp180040en.pdf.

[48] UNHCR, UNHCR fordert für Familiennachzug “transparente, klare und einfache” Regelung, 8 May 2018, http://www.unhcr.org/dach/de/22855-unhcr-fordert-fuer-familiennachzug-transparente-klare-und-einfache-regelung.html. Under the new law, the length of stay will indeed be considered and will be calculated based on the date of application for asylum in Germany.

[49] The final 129 asylum-seekers to be relocated from Greece arrived in Ireland on 23 March, bringing to 1,022 the total number Ireland received under the programme. Ireland has pledged to resettle a further 945 refugees from Lebanon between 2018 and 2019.

[50] European Commission, Member States’ Support to Emergency Relocation Mechanism, 9 July 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/press-material/docs/state_of_play_-_relocation_en.pdf.

[51] UNHCR and IOM, Proposal for a regional cooperative arrangement ensuring predictable disembarkation and subsequent processing of persons rescued-at-sea, 27 June 2018, http://www.unhcr.org/5b35e60f4.

[52] UNHCR has developed a strategy and appeal for 2018 to strengthen access to protection and solutions in countries of asylum and transit along the Central Mediterranean Route – see UNHCR, central Mediterranean Situation: Supplementary Appeal – January to December 2018, http://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2018-03%2008%20-%20Central%20Mediterranean%20appeal_%20FINAL_0.pdf.