DESPERATE JOURNEYS

Refugees and migrants arriving in Europe and at Europe's bordersJANUARY – DECEMBER 2018

A woman weeps, minutes after being saved by the Sea Watch search and rescue ship on 24 June 2016. © UNHCR/Hereward Holland

Executive Summary

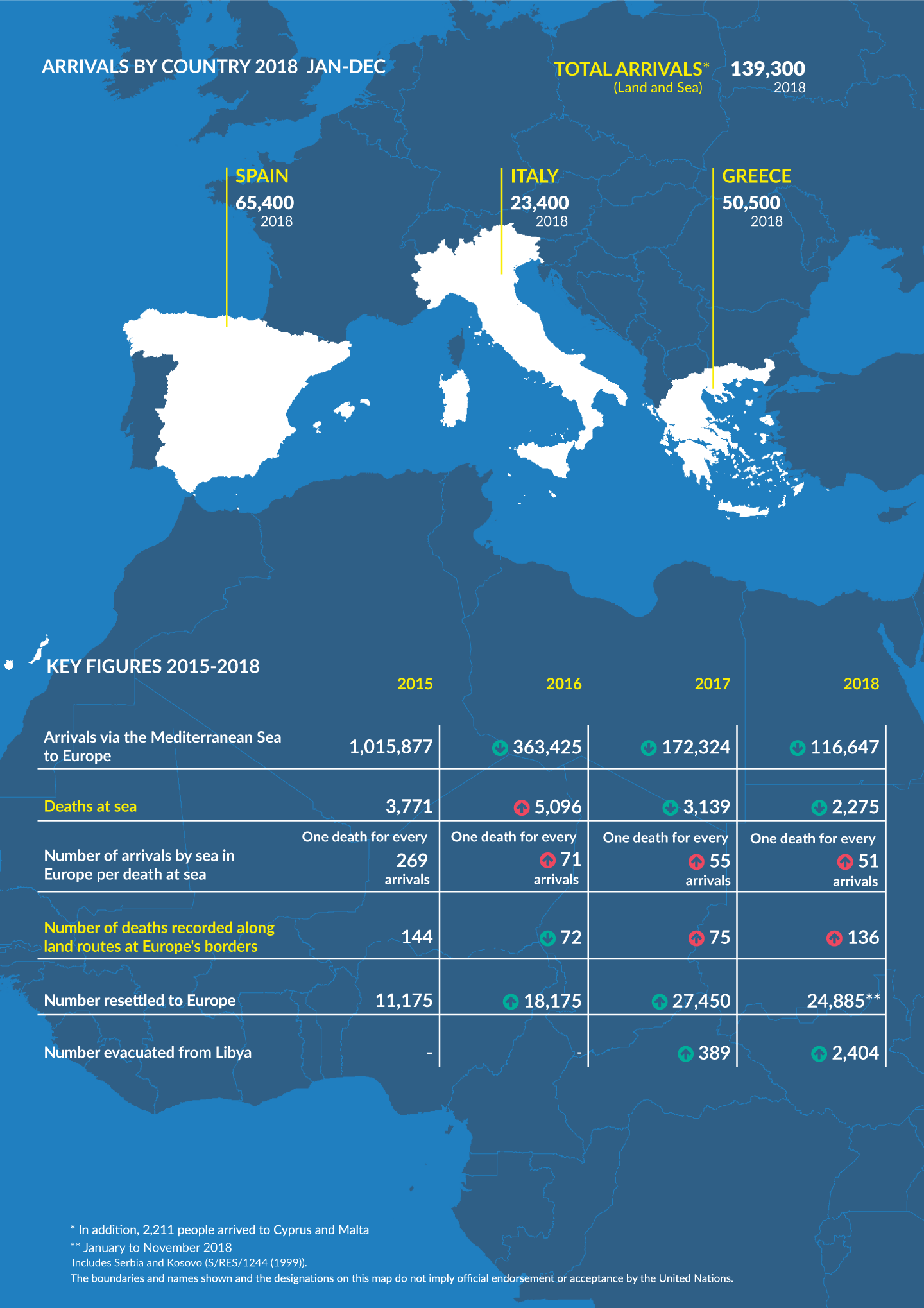

The number of refugees and migrants making the Mediterranean Sea crossing fell in 2018 but it is likely that reductions to search and rescue capacity coupled with an uncoordinated and unpredictable response to disembarkation led to an increased death rate as people continued to flee their countries due to conflict, human rights violations, persecution, and poverty.

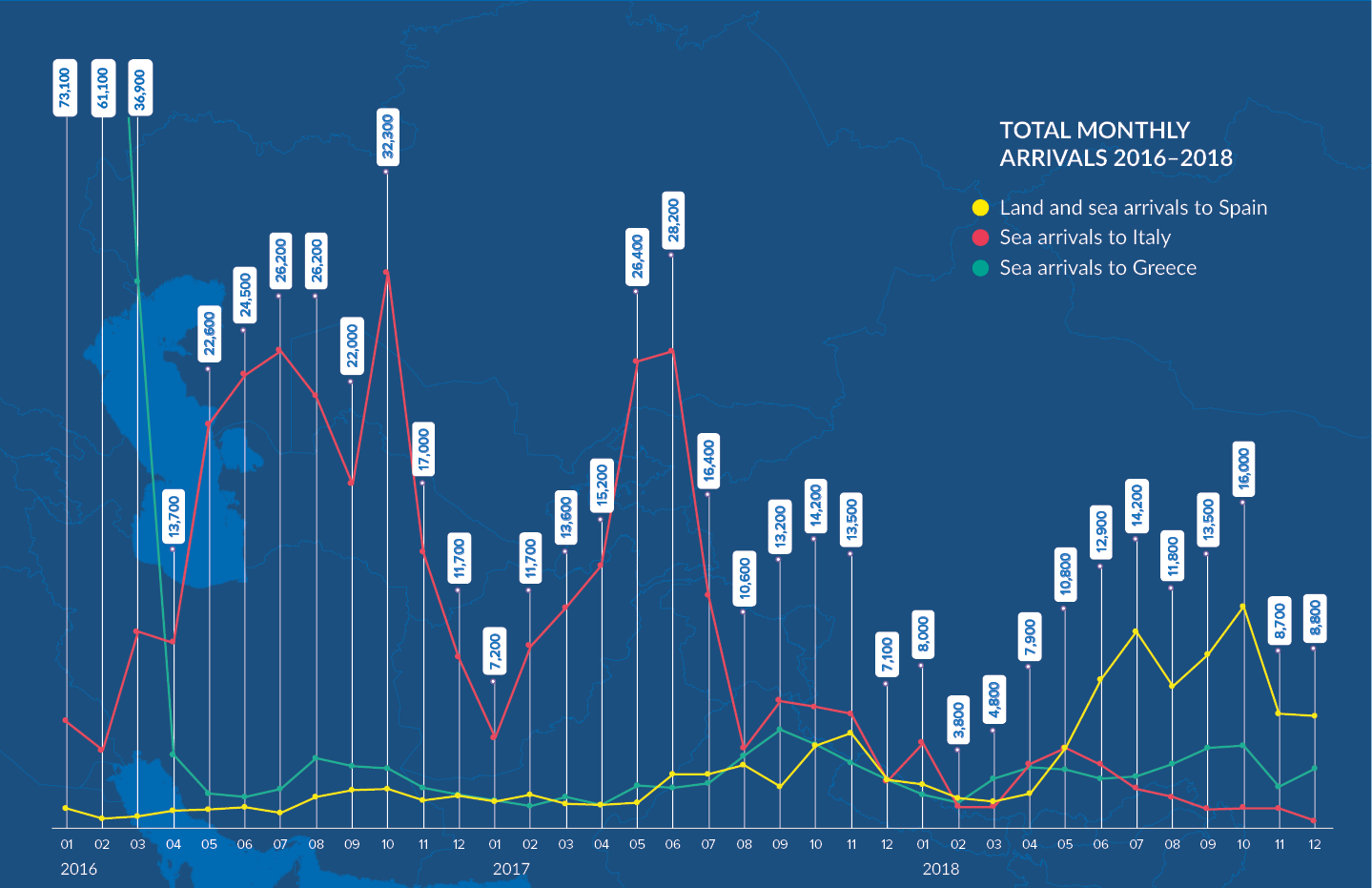

Throughout 2018, there were significant changes to the pattern of routes taken by refugees and migrants heading for Europe. For the first half of the year, more people arrived in Greece than Italy or Spain, in the second half, however, the primary entry point became Spain as more and more people attempted the perilous sea crossing over the Western Mediterranean.

Although arrivals were markedly down compared to the large numbers who reached Italy each year between 2014-2017 or Greece in 2015, the journeys were as dangerous as ever. An estimated 2,275 people perished in the Mediterranean in 2018 – an average of six deaths every day. On several occasions, large numbers of often traumatised and sick people were kept at sea for days before permission to disembark was granted, sometimes only after other states had pledged to relocate the majority of those who had been rescued. By the end of the year, this situation had not been resolved despite UNHCR’s and IOM’s continuous call to establish a predictable regional disembarkation mechanism in the Mediterranean Basin.

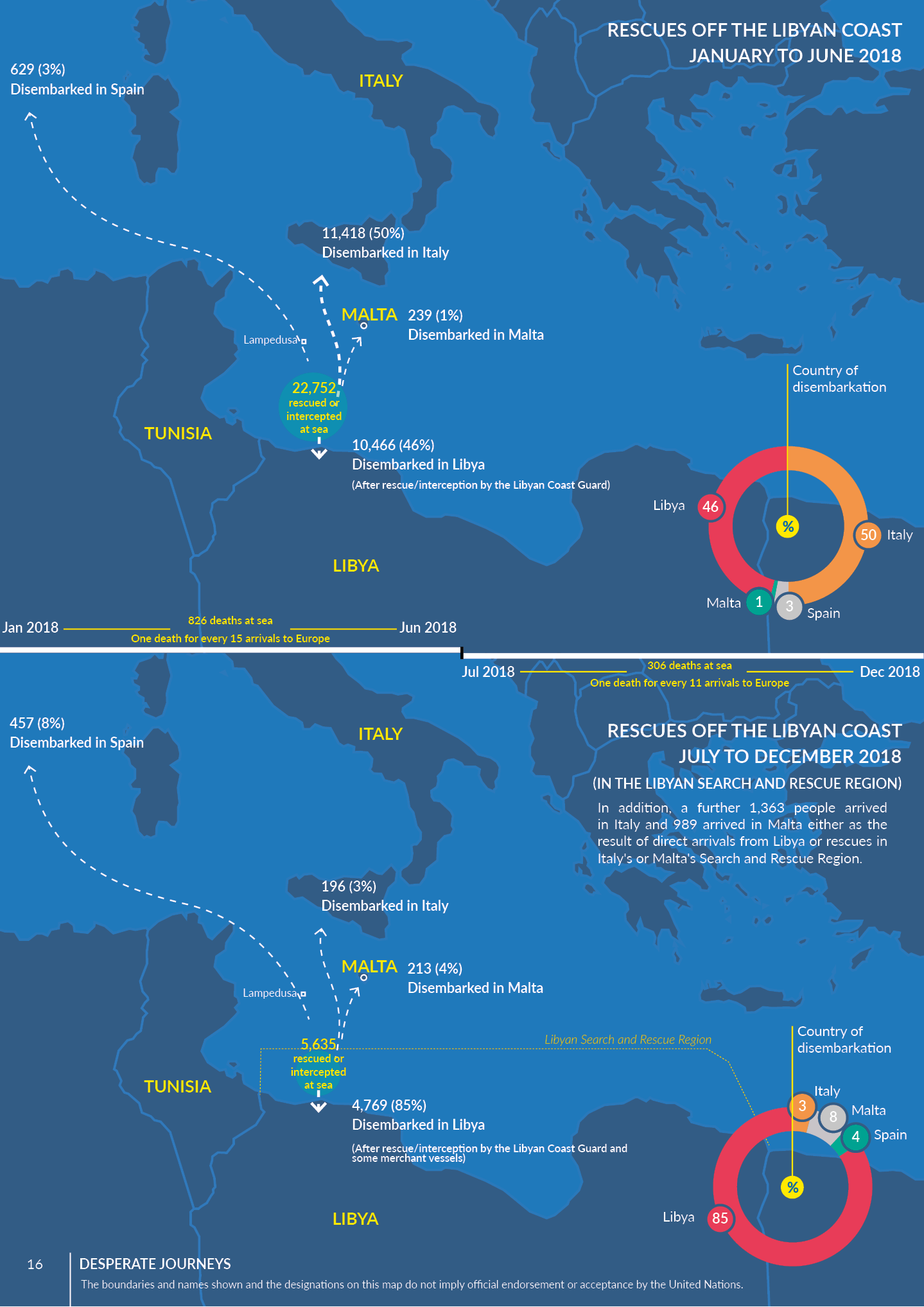

Furthermore, the Libyan Coast Guard stepped up its operations with the result that 85% of those rescued or intercepted in the newly established Libyan Search and Rescue Region (SRR) were disembarked in Libya, where they faced detention in appalling conditions (including limited access to food and outbreaks of disease at some facilities, along with several deaths). As a result, more vessels containing refugees and migrants attempted to sail beyond the Libyan SRR to evade the coast guard – either to make land in Malta and Italy or at least to reach the search and rescue regions of those jurisdictions. This trend is expected to continue in 2019.

Although the overall number of deaths at sea in the Central Mediterranean more than halved in 2018 compared to the previous year, the rate of deaths per number of people attempting the journey rose sharply. On the crossing from Libya to Europe, for instance, the rate went from one death for every 38 arrivals in 2017 to one for every 14 arrivals last year. The toll was particularly heavy in the Western Mediterranean, on the route to Spain, where the number of deaths almost quadrupled in 2018 over the previous year.

Elsewhere in Europe, Bosnia and Herzegovina recorded some 24,100 arrivals as refugees and migrants transiting through the Western Balkans searched for new routes to EU Member States; Cyprus received several boats carrying Syrians from Lebanon, along with arrivals from Turkey and more by air, straining accommodation and processing capacity; and towards the end of the year, small numbers of people tried to make the sea crossing from France to the UK.

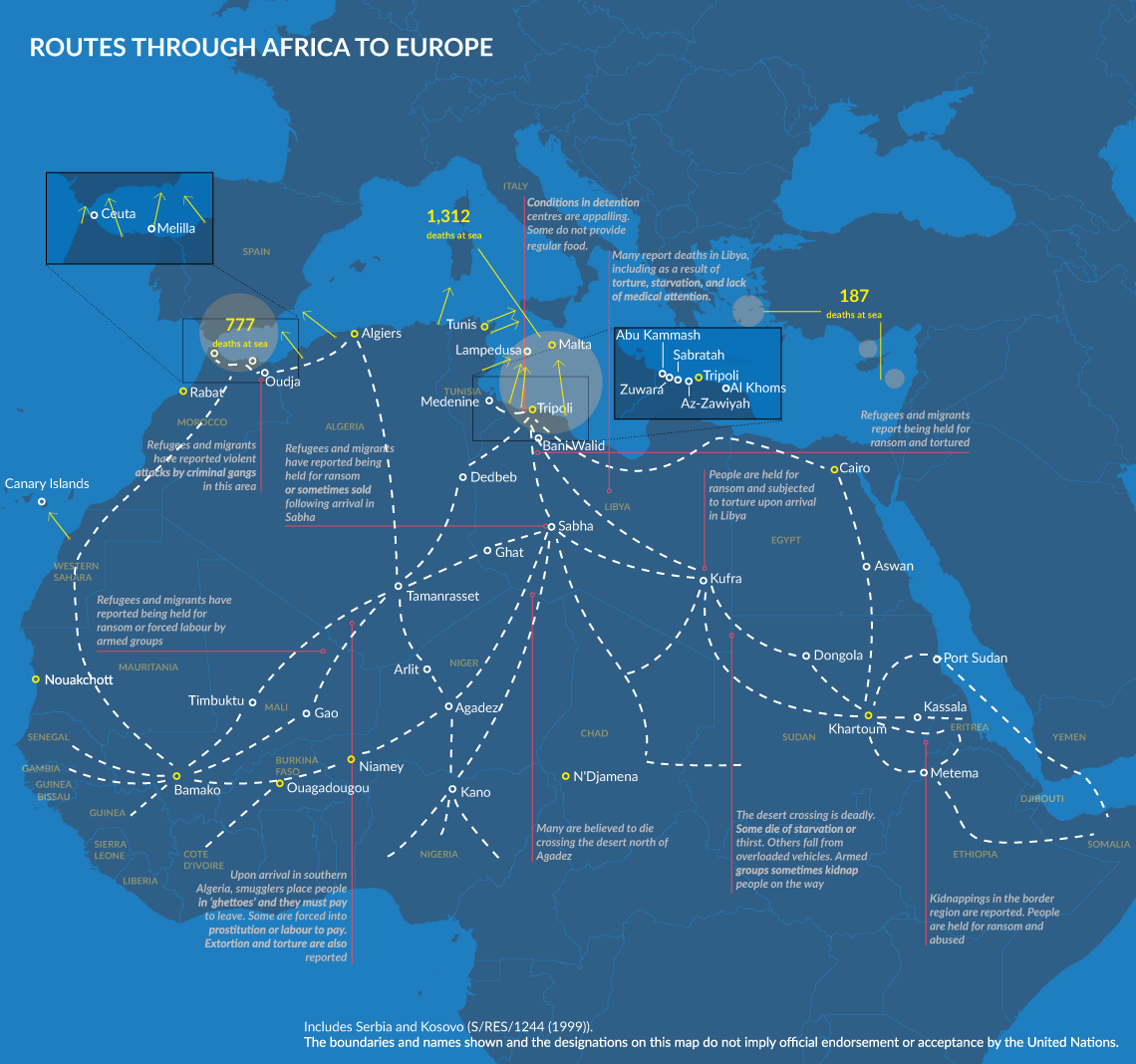

Most of these trends look set to continue in 2019, with the root causes of displacement and migratory movements – such as human rights violations and conflict or poverty – remaining unresolved. For many people, the sea crossing is just the final step in a journey that has involved travel through conflict zones or deserts, the danger of kidnapping and torture for ransom, and the threat from traffickers in human beings. UNHCR is also calling on States to stop apprehending and returning thousands of people to neighbouring countries without allowing them to seek asylum or assessing individually whether they have international protection or other humanitarian needs – a practice known as “push-backs” – as well as to greatly step up efforts to protect children – accompanied or alone – and to provide support for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, as well as better access to safe and legal pathways as alternatives to these dangerous journeys.

The past 12 months did bring some positive developments. More states committed to resettling refugees evacuated from Libya, thus enabling UNHCR to bring more people to safety via the Emergency Transit Mechanism established in Niger. At the end of the year, UNHCR opened the Gathering and Departure Facility in Tripoli, enabling the release of more people from detention. Several EU Member States also committed to relocations of people rescued in the Central Mediterranean – a sign of the potential for joint international action.

Indeed, this report calls for the urgent establishment of a coordinated and predictable regional response to rescue at sea, as well as greater responsibility sharing in general. This should include increased rescue capacity, specified and predictable disembarkation points, more solidarity and support for those countries where most refugees and migrants arrive, improved access to safe and legal pathways (such as resettlement, family reunification, education and labour schemes), greater protection for unaccompanied children and sexual and gender-based violence survivors, and tougher measures against the perpetrators of crimes against refugees and migrants, including traffickers and smugglers.

Recommendations

In response to the concerns outlined in this report, UNHCR calls on European states to:

Rescue at sea and detention in Libya

- Urgently establish a coordinated and predictable regional mechanism to strengthen rescue at sea, especially with regard to disembarkations and subsequent processing;

- Enhance search and rescue capacity in the central Mediterranean, including by removing restrictions on NGOs;

- Urge the Libyan authorities to end the arbitrary detention of refugees and migrants intercepted or rescued at sea; to release the most vulnerable individuals to the community as per the 2017 arrangements; and to amend Law 19 of 2010, which foresees hard labour as a sentence for irregular entry providing a legal basis for the exploitation of refugees and migrants;

Access to territory and asylum procedures

- Strengthen identification of those with international protection needs at borders and provide access to asylum procedures, including for people seeking asylum who arrived irregularly, as well as end push-back practices.

- Make use of accelerated and simplified asylum procedures in case of mixed movements to quickly determine who is in need of international protection and requires integration support, and who is not and thus can be channelled into return procedures;

- Facilitate timely returns, in safety and dignity, of those found not to be in need of international protection or with no compelling humanitarian needs following a fair and efficient procedure;

Protection of children

- End the detention of children for immigration purposes and ensure early identification of asylum-seeking unaccompanied and separated children and their integration within national child protection systems, including through the use of guardianship systems.

- Enhance the availability of accessible information to children on their rights, available services, and asylum processes, and speed up family reunification procedures for children;

Onward movement

- Increase solidarity and support for countries within the region and along key migration routes in order to strengthen access to protection where refugees are located and thus reduce the need for dangerous irregular journeys.

- Such solidarity and support should include a mechanism to relocate asylum-seekers from EU member states receiving a disproportionate number of asylum claims to other EU countries as part of the reform of the Dublin Regulation, as well as help strengthening asylum systems in the Western Balkans along with the primary countries of initial arrival in Europe, including as a means of contributing to reducing irregular onward movement;

- Ensure efficient and quality family reunion procedures for refugees who have arrived in the EU and have family in other EU countries, which could address one of the main causes of irregular onward movement, including for children;

Access to safe and legal pathways

- Enhance access to safe and legal pathways by further increasing resettlement pledges, including for people evacuated from Libya, taking steps to make family reunification with all beneficiaries of international protection fully accessible by removing practical and legal obstacles, and promoting complementary pathways of admission including community-based sponsorship programmes, scholarship programmes and labour mobility schemes;

Protection against dangers

- Strengthen the timely identification of survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, including male and child survivors, and ensure their referral to adequate multi-sectoral services;

- Enhance efforts, including cross-border cooperation and information sharing, to bring the perpetrators of crimes against refugees and migrants, including traffickers and those involved in kidnappings for ransom, to justice.

2018 trends overview

In 2018, human rights violations, persecution, conflict, and violence continued to displace many with some subsequently seeking international protection in Europe.[1] While refugees and migrants arriving in Europe continued in general to be from the same countries of origin or the same regions as in 2016 and 2017, there were significant changes in movement patterns, in part in response to new restrictions. An estimated third of people who arrived in Europe via the Central Mediterranean route in 2018 were likely to be in need of international protection,[2] along with approximately half of people who arrived via the Eastern Mediterranean sea route, and around 10% of those who arrived in Spain via the Western Mediterranean route.[3]

Spain became primary sea entry point: In the first half of the year, more people entered Europe via Greece than Italy or Spain, partly because of an increase compared to 2017 in the numbers crossing the land border from Turkey. Most of those arriving in Greece were from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan with many likely to be in need of international protection. In the second half of the year, fewer Syrians arrived by sea in Greece, comprising just 14% of all sea arrivals compared to 38% in the first six months. At the same time, the number of people crossing the sea to Spain increased from May onwards,[4] with more than 10,200 arrivals in October, making Spain the primary entry point to Europe in the latter half of the year.[5] While there were again many Moroccans amongst these arrivals, there were also increased numbers from Guinea and Mali (including those displaced by violence in north and central Mali)in particular compared to 2017, as well as from Côte d’Ivoire and The Gambia, while more Algerians crossed to Spain in the latter months of the year. Those using this route were thought to do so for a variety of reasons, with some motivated by economic factors and others seeking asylum. Among those arriving in Spain seeking international protection were people fleeing gender-related persecution such as forced marriage and female genital mutilation, persecution on account of sexual orientation or gender identity, and political persecution.[6] Others arriving in Spain via this route potentially in need of protection included victims of trafficking and unaccompanied children. As arrivals by sea to Spain increased, the number of deaths at sea along the Western Mediterranean route almost quadrupled,[7] reportedly in part due to new smuggling practices that encouraged vessels to depart regardless of the weather conditions.[8]

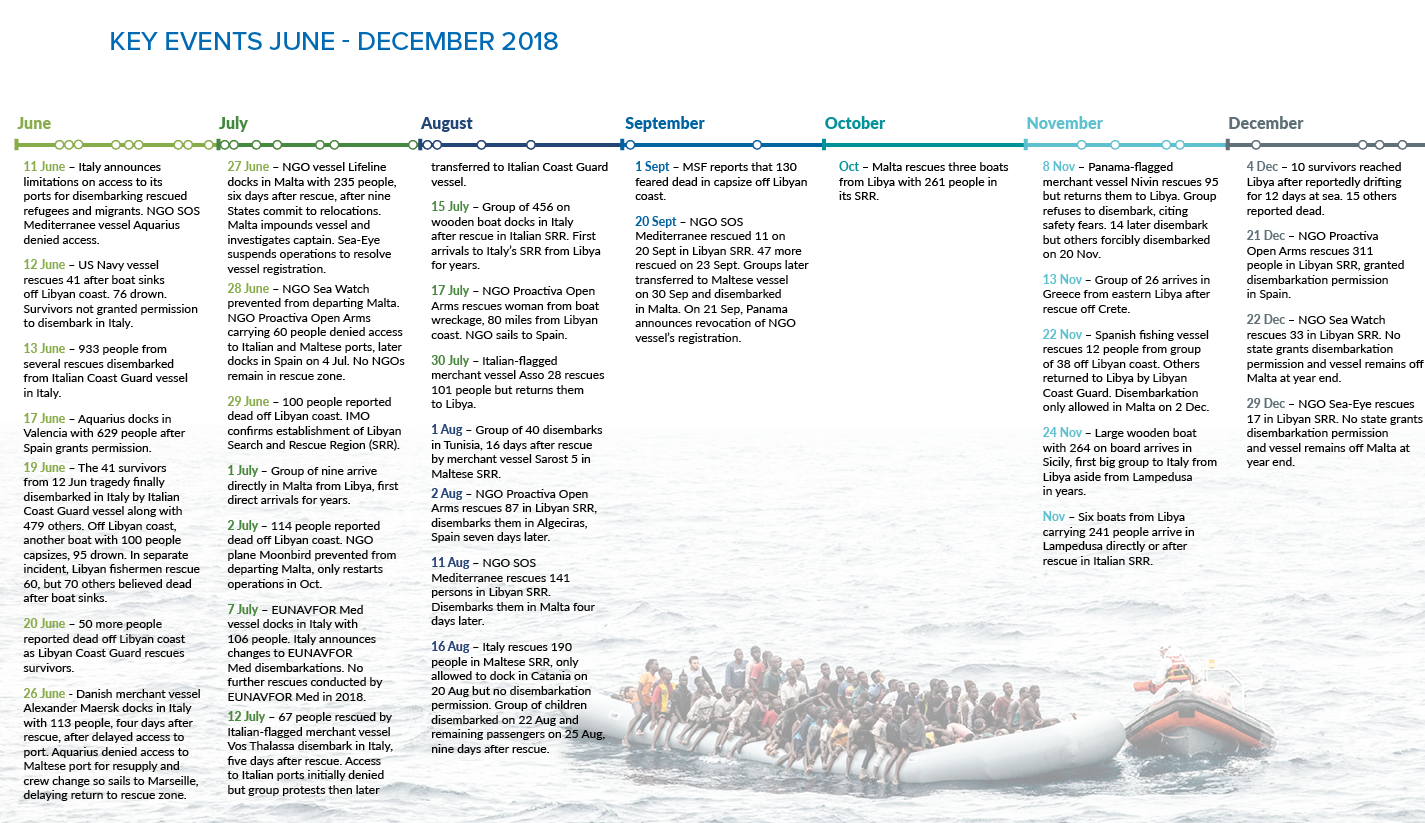

Further reduction of search and rescue capacity in the central Mediterranean: Although sea arrivals to Italy had already dropped significantly from July 2017 onwards, they fell even further from June 2018 onwards; that followed Italy’s decision to no longer allow refugees and migrants rescued off the coast of Libya by NGOs and merchant vessels, in what became the Libyan Search and Rescue Region (SRR),[9] to disembark at Italian ports. After this decision, a combination of reduced search and rescue operations by European state vessels off the Libyan coast, increased rescues and interceptions by the Libyan Coast Guard, and further restrictions on NGOs, led to some boats carrying refugees and migrants sailing further from the Libyan coast, traveling for over 100 miles to beyond the Libyan SRR[10] and either landing directly in Malta and Italy or being rescued in Italy’s and Malta’s SRRs, the first such regular occurrences in years[11]. This new pattern meant refugees and migrants spent longer at sea in rickety vessels, sometimes without food and water for several days,[12] before making land or being rescued. In the absence of a consistent and predictable approach to the disembarkation of rescued persons,[13] on several occasions there were significant delays between a rescue and the subsequent disembarkation while permission for access to a safe port was sought,[14] and at times disputes arose over which state was responsible for the rescue of a vessel and its passengers and their subsequent disembarkation once it had passed beyond the Libyan SRR. There were also signs that merchant vessels were becoming more reluctant to rescue boats in distress in view of the difficulties others had encountered in being granted access to safe ports for disembarkation.[15]

One positive development was the relatively quick commitments by some European states to relocate some of those who were rescued at sea, mostly by NGO vessels, and who were permitted to disembark in Italy, Malta, or Spain on condition of their subsequent transfer to another European country. France, Spain, Germany, and Portugal committed to relocating the largest numbers of people. Nevertheless, the process of selection and transfers was often marred by inconsistencies in the procedures and criteria applied, resulting in significant delays in the transfer arrangements and, in some cases, with refugees and migrants being kept in prolonged detention during this process.[16]

In 2018, the number of deaths in the central Mediterranean dropped by 54% in comparison to 2017.[17] However, there was a significant increase in the rate of deaths compared to the number of arrivals in Europe. There was one death for every seven arrivals in Europe from Libya in June (when over 450 people are believed to have died after leaving Libya)[18] and one death for every 14 arrivals from Libya in 2018 as a whole (compared to one for every 38 arrivals from Libya in 2017)[19] as a result of the big reduction in overall search and rescue capacity. Additionally, the Libyan Coast Guard’s increased capacity and operational area (following the formalization of Libya’s SRR in mid-year) resulted in an increased proportion of refugees and migrants intercepted or rescued at sea and transferred to detention in appalling conditions in Libya. In September, UNHCR released an updated position advising against any return of refugees and migrants rescued at sea to Libya on account of the volatile security situation along with the particular risks for non-nationals such as detention in substandard conditions and reports of serious abuses of asylum-seekers, refugees and migrants.[20]

Shifting routes through the Balkans: Another key movement trend in 2018 was that more refugees and migrants travelling through the Balkans, usually from Greece and Bulgaria, tried to transit through Bosnia and Herzegovina to other EU member states. Most of those detected in Bosnia and Herzegovina were from Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria. These included people who had travelled north from Greece via Albania and Montenegro, as well as those moving on from Serbia, as entry from Serbia to Hungary via the two ‘transit zones’ to seek asylum became even more restricted than in 2017.[21] The increased numbers in Bosnia and Herzegovina prompted the international humanitarian community to work with government counterparts to strengthen capacity in order to respond more effectively to the needs of asylum-seekers while addressing the situation of migrants, improve reception conditions (especially in the most affected Una-Sana Canton, in the north of the country), as well as increase basic services, including health services, before the onset of winter. However, conditions remain precarious.

More arrivals in Cyprus: In the eastern Mediterranean, almost 7,800 new asylum applications were lodged in Cyprus in 2018. This increase has stretched the capacity of the asylum system as well as contributed to homelessness among some asylum-seekers, highlighting the need for improvements to reception capacity and asylum processing. While the overall number of sea arrivals to Cyprus dropped compared to 2017, several boats carrying Syrians arrived directly from Lebanon, in addition to those crossing from Turkey. Some of those arriving by sea reported travelling via that route in order to join close family members already in Cyprus.[22]

Increased attempts to cross to England by boat: Towards the end of the year, there were a number of attempts to cross from France to England by sea.[23] For many years, refugees and migrants[24] have been trying to cross this border in different ways, many of them highly dangerous, such as hiding on trucks, trains or ferries. Since 2015, at least 55 people have died attempting this journey (including five in 2018), mostly the result of accidents involving trucks or other vehicles. While the sea crossings represent a new way of trying to cross the border, the number attempting the journey so far has been relatively small, especially compared to other routes in the region.

Staff from UNHCR and IOM help 150 refugees and migrants disembark the Italian Coast Guard ship, Diciotti, in the port of Catania on 25 August 2018 after a 10 day stand-off. © UNHCR/Alessio Mamo

Likely trends in 2019

As of early 2019, most of these trends are expected to continue over the coming months. Until the root causes and triggers of displacement and migration are addressed in many countries in nearby regions, people will continue to seek safety and protection, while others will try to escape poverty with the hope of finding work or educational opportunities. For example, forced displacement from Mali,[25] northern Nigeria,[26] Cameroon,[27] Burkina Faso,[28] and western Niger[29] could contribute to onward movement towards Europe via the Central Mediterranean or Western Mediterranean routes.

Given the high number of arrivals by sea in the latter half of 2018, Spain seems likely to continue to be the primary entry point to Europe. This will require further solidarity and efforts to improve reception conditions, along with ensuring fair and efficient asylum procedures for those seeking international protection. Given the situation in Syria and other parts of the region, similar numbers are likely to continue to try to cross to Greece from Turkey, including at the land border. The freezing temperatures in winter along with the dangerous river crossing lead to several deaths each year at the land border. Further measures are needed to guard against loss of life, including ending push-backs.[30]

In the central Mediterranean, indications from the latter half of 2018 suggest that some of those currently in Libya, many of whom have likely been there for a year or more, along with some more recent arrivals to Libya may continue to try to leave, with some smugglers adapting their methods by providing sturdier boats, more fuel and satellite phones, and sometimes escorting or carrying boats further from Libya so as to move beyond the area patrolled by the Libyan Coast Guard. In the continued absence of a consistent and coordinated approach within the region to rescue at sea and subsequent disembarkation, rescues by NGO vessels and possibly others, in particular in the Libyan SRR are likely to continue to be responded to on an ad hoc, case by case basis. As a result, there will be more situations in which often severely traumatised people are kept at sea for several days while governments debate where they can be disembarked. The high death rate is also likely to continue, given the worrying reduction in search and rescue capacity. Malta, along with Lampedusa, may continue to receive an increase in direct arrivals.

Elsewhere, refugees and migrants are likely to keep trying to travel irregularly through the Balkans, with routes possibly varying depending on restrictions imposed by different states in the region. Further efforts are needed in 2019 to strengthen asylum procedures in the region, along with better and harmonized reception conditions, improved child protection and other services for persons with specific needs, and support for integration, including as a means of helping to reduce onward movement.

Following improved commitments to the provision of safe and legal pathways to protection in 2018, including within the framework of the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF), UNHCR urges European states to continue to provide increased numbers of resettlement and humanitarian admission places (including for those evacuated from Libya), and to address obstacles preventing refugees from realising their rights to family reunification. UNHCR is also encouraging further steps to granting access to legal pathways, including private sponsorship schemes, scholarship programmes and labour schemes, as an alternative to the dangerous irregular journeys described in this report.

Issues of concern for UNHCR

Among those arriving in Europe in 2018 were people fleeing conflict, insecurity and human rights violations in Mali, Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Sudan, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Somalia; forced conscription and other human rights abuses in parts of East Africa; and other forms of persecution in various countries.

Dangers and deaths along the way

Those traveling to Europe continued to face considerable dangers on certain parts of the routes, with many refugees and migrants dying along the way. Despite knowing the general risks of travelling to and through Libya, for some the push factors appeared to outweigh these dangers.[31]

Six killed daily on average in Med: An estimated 2,275 refugees and migrants died in the Mediterranean Sea in 2018,[32] making an average of six deaths every day. Most deaths took place after departure from Libya (more than 1,100), with several boats capsizing – there were at least 10 incidents in which 50 or more people drowned.[33] These deaths came at a time when NGOs faced further restrictions on their activities, with some forced to remain in port or to spend longer periods transiting to ports for disembarkation or resupply.

Along the sea route to Spain, the number of deaths almost quadrupled as more people tried to cross in unsafe vessels, sometimes in poor weather, including on the longer journey over the Alboran Sea. Although the number of persons per boat tends to be lower than along the route from Libya, there were still 12 incidents in 2018 in which 20 or more people died. Despite the short distance between the Greek islands and Turkey, more than 120 people drowned last year, including incidents where boats capsized at night, including as winter set in. In addition, there were 64 deaths reported in four incidents as refugees and migrants tried to cross from Turkey or Lebanon to Cyprus.

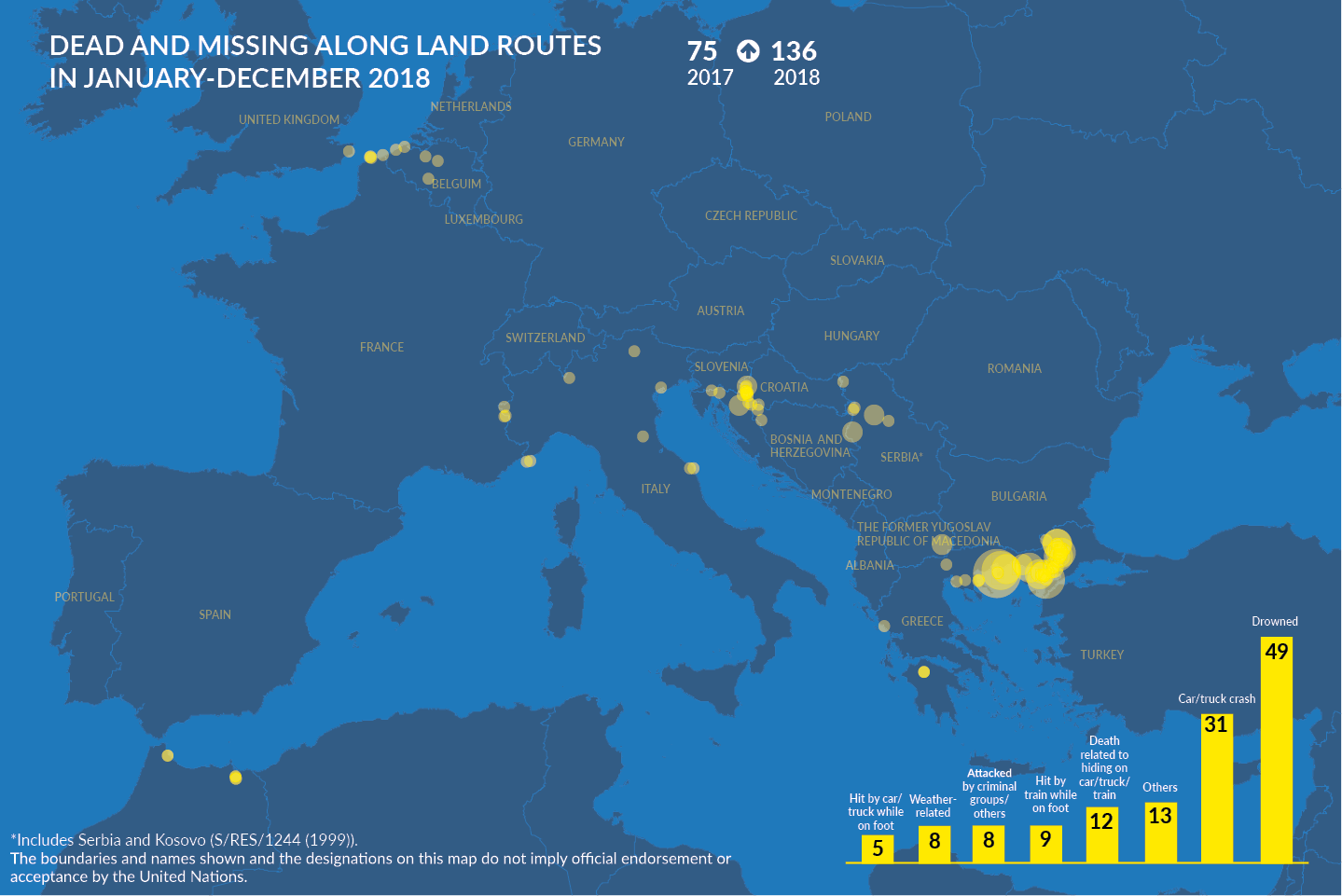

Deaths along land routes: For many, the sea journey is just a final step of a much longer and often very dangerous journey that has included passing through areas of armed conflict, crossing deserts, and for some, being held for ransom and tortured, or trafficked for sexual or labour exploitation. Many others are known to die each year along the routes to and through Libya[34] as well as en route to Morocco, including while crossing the desert or in the custody of smugglers or traffickers. For example, in a forthcoming UNHCR report based on interviews with people who had crossed the sea to Italy, at least 44% reported witnessing deaths during their journeys.[35]

In addition, at least 136 people died along land routes at Europe’s borders or within Europe last year. Areas of particularly high risk included the Evros River, at the Greek-Turkish border, where at least 27 people drowned (usually after their boats capsized); the road between the Greek-Turkish land border and Thessaloniki, where at least 29 people died in vehicle accidents;[36] the Croatian-Slovenian border, where 11 people died, of whom nine drowned in the Kupa/Kolpa River; and the Italian-French border, where there were five deaths, including three along a route through the Alps. At the borders between Morocco and the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, at least six deaths were reported of which four took place during or after attempts to cross the fence.

Rescue at sea in the central Mediterranean

Six months after Italy’s decision to end the disembarkation in Italian ports of people rescued off the Libyan coast, disembarkations following rescue at sea operations (aside from those conducted by the Libyan Coast Guard or by Maltese or Italian authorities) continue to be handled on a case-by-case basis by coastal EU states in coordination with other EU member states who are willing to consider relocations. In 2018, this sometimes resulted in refugees and migrants having to wait several days before being allowed to disembark.[37] Vessels engaged in sea rescues face uncertainty over access to nearby safe ports and there have been some reports from survivors of vessels passing by without assisting before they were eventually rescued.[38] In other instances, there were disputes between European states over whether or not a vessel was in distress as it was passing through one state’s search and rescue region, coupled with allegations of avoiding their responsibility to carry out rescues.

In the latter half of 2018, some indication of smugglers adapting to the new circumstances emerged, with at least 31 boats managing to travel beyond the Libyan SRR since the start of July, something that usually requires a sturdier boat, sufficient fuel and a navigational device. In at least one incident, smugglers reverted to a tactic in use some years ago of initially transporting a group on a larger vessel before transferring them to a smaller boat for the final part of the journey to Italy.[39]

Reduced search and rescue capacity and the Libyan Search and Rescue Region: In June, the search and rescue capacity of European state vessels in the central Mediterranean was further reduced.[40] After mid-June, the Italian Coast Guard and Navy – which up until that point had rescued over 2,600 people that had departed from Libya in 2018 – conducted no further rescues off the Libyan coast. Similarly, vessels deployed to EUNAVFOR Med’s Operation Sophia, which up to May had rescued over 2,200 people, subsequently rescued only one more group between June and December 2018.[41] The NGOs that between January and May had been responsible for the rescue of almost 5,000 people suddenly faced new restrictions that reduced their presence in the rescue zone.[42] Merchant vessels which before June had rescued almost 600 people were suddenly required to rescue more than 700 people in June alone. They too later faced restricted access to ports. After June, only two more rescues by merchant vessels resulted in a total of 79 people who had departed from Libya being disembarked in Europe.[43]

The reduction in search and rescue capacity in 2018 was not, however, in response to fewer people departing from Libya. It occurred in June, a month when over 6,900 people departed from the Libyan coast, and it most likely contributed to the more than 450 deaths off the Libyan coast that month.[44] The question of having sufficient rescue vessels in the area was particularly relevant given that in 2017, most of those rescued after departure from Libya had been spotted at sea, rather than after a distress call was issued.[45]

With the reduced presence of most European and NGO search and rescue actors in the second half of the year, and following the formalization of a Libyan SRR at the end of June – stretching more than 110 miles from some primary departure areas – the Libyan Coast Guard took on a greater role despite its limited capacity. Consequently, in the second half of the year, 85% of persons rescued or intercepted in the Libyan SRR were disembarked in Libya. This is in stark contrast to the first half of the year, when 54% of those rescued in what became the Libyan SRR were disembarked in Europe.

The establishment of an SRR means that, in line with obligations arising from international maritime law, a state commits to coordinating search and rescue operations within the region and exercises primary responsibility when the rescue takes place within its SRR to ensure cooperation and coordination for disembarkation. However, international maritime law does not prescribe where persons rescued in that region must be disembarked as long as the port is safe and disembarkation is effected as soon as reasonably practicable. NGOs and commercial vessels involved in search and rescue have noted that on some occasions the Libyan Coast Guard requested that persons rescued in international waters were to be handed over to them, so that they could be disembarked in Libya.[46] UNHCR remains concerned about a few instances of rescues in international waters which, following instructions from Libyan authorities, resulted in returns to Libya, despite UNHCR’s non-return advisory. Reports have also drawn attention to some other coordination challenges within the Libyan SRR, including a lack of response to calls on some occasions,[47] and lack of coordination with NGOs who were available to assist.[48]

Inhuman detention conditions in Libya: People rescued or intercepted at sea and disembarked in Libya are subsequently transferred to detention centres.[49] Conditions in those centres are appalling;[50] for example, in November, UNHCR reported that detainees in some facilities were given limited access to food, while there were also reports of an outbreak of tuberculosis.[51] Several people were also reported to have died in official detention centres last year.[52]

In December 2018, the Gathering and Departure Facility (GDF) for vulnerable refugees and asylum-seekers opened in Tripoli.[53] The GDF is the first of its kind in the country and is intended to bring vulnerable refugees and asylum-seekers to a safe environment while solutions – including resettlement, family reunification, return to a country of previous admission or evacuation to emergency facilities – are identified. The facility, managed by UNHCR, LibAid and the Ministry of Interior, represents one of a range of measures offering viable alternatives to detention. As noted in UNHCR’s September advisory, the establishment of the GDF does not change the agency’s position that Libya cannot be designated as a place of safety for the purpose of disembarkation.[54]

Since its opening, 220 refugees have been transferred from the GDF to the Emergency Transit Mechanism (ETM) in Niger and to Italy. While this is a very positive step, in December UNHCR noted that of an estimated 4,900 persons in official detention centres in Libya, around 3,650 (74%) were thought likely to be in need of international protection.[55] UNHCR continues to advocate for an end to arbitrary detention and for immediate release to the community of those most vulnerable as per the 2017 arrangements.[56]

UNHCR and IOM continue to call for the establishment of a consistent and predictable response to rescue at sea in the central Mediterranean. This should include determining of places of disembarkation and additional pre-identified disembarkation centres in EU territory and potentially elsewhere based on a geographic distribution, with due respect for the safety and dignity of all people on the move. This would also include access to adequate, safe and dignified reception conditions; processing to establish particular needs, including international protection needs; and subsequent solutions, which may include resettlement or humanitarian admission, transfer to another EU member state,[57] family reunification, local solutions, or voluntary repatriation, as appropriate.[58]

Journeys through Libya

An Eritrean father hugs his daughter at UNHCR’s Gathering and Departure Facility (GDF) in Tripoli after UNHCR secured the release of 133 refugees from five detention centres across Libya in early December 2018 and hosted them at the GDF until arrangements for their evacuation to Niger were concluded. © UNHCR/Farwa Harwida

By the time refugees and migrants step onto a boat at the Libyan coast, many will have been tortured, raped, held for ransom, and seen people die around them.[59] In 2018, refugees and migrants arriving in Europe from Libya, and those evacuated to Niger from Libya, continued to report multiple experiences of violence and exploitation. Most arrivals to Europe from Libya were from Eritrea, Sudan and Nigeria. Many of those interviewed by UNHCR had been held in Libya for one year or more, often for ransom or forced labour.

A young Somali man evacuated to Niger from Libya told UNHCR:

“Where I am from in Somalia, there was extreme drought. People were dying and there was no work. So in 2016, I made the decision to leave. Honestly, I thought it was bad in Somalia…but the things I have seen since then on the journey here…people being electrocuted, being tortured, people dying even.

When I left, I didn’t know where I would go, or how I would get there. I took around $1,000 with me, and paid all of it to smugglers in Libya. I went first to Yemen and took a boat for some weeks across to the sea to Sudan. They took all of our luggage and threw it away. On that journey, nobody cares if you live or if you die. The boat was not even big enough to carry us all.

When we arrived in Sudan, smugglers took us in a car. There was not enough space in the vehicle. They put people on top of one another. But if you complained, they would beat you. We barely ate for two weeks. We couldn’t. Many people were sick and vomiting, two people even died. When we arrived to Libya, we were forced into an underground hole. So many people were sick. My good friend was so sick that he died there…You can’t sleep in the hole. There are maggots all over you, eating your skin. They give you a phone to call your family to ask for money, and they beat you and electrocute you. When I refused to call my family, they tied my hands and feet, and poured water all over me and electrocuted me…they electrocute you until your whole body shakes.”

Of those traveling from the East and Horn of Africa, some reported being kidnapped and held for ransom while crossing the border between Eritrea and Sudan, with the kidnappers demanding up to $8,000 for their release. Many, including women and children, reported being subjected to different forms of violence while being held, including sexual violence.[60] While crossing the desert from Sudan to Libya, refugees reported being kidnapped by armed groups, raped, being held in warehouses in border towns, often for a year or more, and starved, subjected to torture and other abuse as payments were sought from family or community members.

An Eritrean woman later evacuated from Libya to Niger described her journey by truck from Sudan:

I wish I hadn’t taken that truck. We were only three girls amongst us. The journey through the Sahara to Libya took seven days…and they raped us each and every day…the smugglers…. At the end of the seven days, the smugglers gave us to other smugglers in Libya. They kept us locked up for two weeks. They beat us every day, but at least they did not rape us. We were supposed to move onwards from that place, but someone kidnapped us. Between us, we had to pay him $6,500, and then he just gave us back to the other smugglers.

From there, we were taken into another smuggler’s network. We were taken to a town in southern Libya, where we were held captive from February until November in 2017. They beat us to force us to pay them. For the men, they would burn plastic and let it melt onto their skin to torture them. They would heat up metal spoons on the fire and press it on their skin. I don’t know for sure, but we heard at least 10 people died there from the torture.

On 14 March, during a rescue and search operation, Libyan Coast Guards (LCG) intercepted a boat off the Libyan coast, with 132 refugees and migrants onboard. UNHCR and partners were present at the disembarkation point, at Tripoli Naval base, and provided medical assistance, food, water, blankets, dry clothes and hygiene kits. © UNHCR/Sufyan Said

Many people interviewed by UNHCR once in Europe reported that even though they had paid the ransoms, they were again detained for further ransom, sometimes after being kidnapped by other armed groups. Some recounted how they had tried to cross the sea from Libya but had been intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard and returned to detention.[61]

Among those who arrived in Libya from West Africa, some, including unaccompanied children, also reported being held by armed groups on arrival and said they had then been either tortured for ransom or made to engage in forced labour before being suddenly released and taken to the coast to cross the sea.[62]

In November 2017, speaking at the UN Security Council, UNHCR’s High Commissioner stated that “strong, collective action is needed to tackle the horrific abuses perpetrated by traffickers and to identify and prosecute them.”[63]

As a result of this repeated abuse and mistreatment, many amongst some groups arriving by sea from Libya were severely malnourished. Information gathered by UNHCR officials at disembarkation points in Italy and in the different phases of the domestic asylum system in Italy, along with available research on the subject,[64] suggests that the vast majority of women and girls, as well as many men and boys had been victims of torture and sexual and gender-based violence, including sexual assault and rape, sometimes by multiple perpetrators, during their journeys.

Refugees participating in focus group discussions in the East and Horn of Africa as part of UNHCR’s “Telling the Real Story” (TRS) information campaign continued to report that despite being aware of some of the risks, some still felt that they had no alternative but to undertake the dangerous journey through Libya because of the lack of options in refugee camps. Among their concerns were the ability to continue their education, opportunities to earn money to support their family at home, and the chance to join family members.

Children also told the TRS team that smugglers had approached them with various schemes such as ‘Go now, pay later’, ‘Travel now for free and work when you arrive in Libya’, ‘Get three friends to pay and you travel for free’, and ‘Collect five people and you can all travel free and work on arrival’. Such schemes are known to contribute to people subsequently being held for ransom, and often subjected to torture. Some also noted that smugglers had started using children to pass on information and to recruit others.

Access to territory

People seeking international protection need access to a state’s territory in order to be able to lodge an asylum application and enjoy protection from return until their status has been determined. In 2018, UNHCR continued to hear accounts directly from concerned individuals and from partner organizations about certain states apprehending persons who have irregularly entered their territory and returning them to a neighbouring country (such as by simply transporting them across a river or taking them to a border area and sending them across) without providing them with any opportunity to seek asylum or conducting any individualized assessment of their possible international protection needs. UNHCR refers to such irregular returns as ‘push-backs’ that – depending on the circumstances – could amount to refoulement.

Push-backs increase and spread: There were consistent reports relating to thousands of people who had been pushed back to a neighbouring country by police and other authorities of several countries in the region. UNHCR and its partners and/or other NGOs reported frequent push-backs from Bosnia-Herzegovina,[65] Croatia,[66] the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia,[67] Greece,[68] Hungary,[69] Romania,[70] Serbia,[71] Slovenia,[72] and Spain[73] during 2018. Several reports were also received regarding push-backs from Albania, Bulgaria, and Montenegro, while the legality of practices applied at the French-Italian border has been challenged by NGOs.[74]

In addition to the denial of access to asylum procedures for those seeking international protection, push-backs may constitute a violation of the prohibition against collective expulsions.[75] States have the right and duty to manage their borders. However, this is subject to their obligations under national, European, and international law on the protection of asylum-seekers and refugees. Push-backs may also expose people to extreme dangers, including putting lives at risk, depending on the use of violence by the authorities as well as weather conditions.

Unaccompanied children are especially vulnerable as they travel to and through Europe. In 2018, UNHCR and its partners in Serbia received reports of more than 400 unaccompanied children being pushed back from neighbouring states. Over 270 of the children reported having been denied access to asylum procedures and 90 reported having been subjected to physical violence.

Onward movement

A continued trend in 2018 was that some refugees and migrants attempted to move on from the country in Europe where they had first arrived.[76] There is no obligation for asylum-seekers to seek asylum at the first effective opportunity, but at the same time there is no unfettered right to choose one’s country of asylum. For example, people who had initially arrived in Greece, Bulgaria, Italy and Spain attempted to reach other states in Europe. Some were hoping to join family members while some sought to benefit from effective protection that was not available where they had initially arrived,[77] and still others were looking for economic opportunities or standards of treatment that are (or are perceived to be) higher elsewhere. In addition, limited durable integration perspectives and poor reception conditions are often also reported by those moving onward.

Irregular onward movement from Greece and Bulgaria is understood to contribute to the consistent number of people trying to transit through the Western Balkans to other EU member states. Routes have included attempts to travel on from Greece to Italy by boat or ferry, from Bulgaria to Serbia or Romania, or from Greece via the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia or Albania, and on through other states in the region to a final destination. In the countries through which people transit, many either apply for asylum or at least express an intention to do so, primarily as a means of temporarily regularising their status in the country, and then move on. For example, of the more than 22,100 people who expressed their intention to seek asylum in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2018, only 7% subsequently submitted an asylum application.[78] As of December 2018, just over 5,200 refugees and migrants were understood to remain in the country. In Serbia, of the almost 8,500 people who expressed their intention to seek asylum, only 4% subsequently applied. Similarly, in Albania, of 4,000 people who applied for asylum in 2018, only 1% had not abandoned the asylum procedure, and had expressed their interest in staying in that country.

In response to onward movement from Italy, neighbouring states and others have introduced measures such as the reintroduction of border controls and the strict implementation of bilateral agreements for joint patrols of the border and readmission procedures. In addition, in order to reduce the number of migrants and asylum-seekers present at the Italian-French border of Ventimiglia, Italian police authorities implemented transfers of migrants and asylum-seekers there to the hotspot centres located in the south of Italy, on at least a monthly basis.

Elsewhere, following the increased sea arrivals to Spain, more people have been observed traveling onwards to France than in 2017. Most crossings take place from the Spanish town of Irun to the French town of Bayonne and, according to local actors, most of those crossing are single men coming from French-speaking countries in West Africa, who have not applied for asylum in Spain.

This onward movement poses challenges for states such as administrative duplication and additional costs because of the increased demands on national reception capacity and asylum systems, and can also pose risks to refugees and asylum-seekers. In 2018, at least 57 people died after arriving in Europe and traveling onwards from one state to another. This included 32 deaths in the Western Balkans – nearly half drowning in rivers that form borders between states, as well as seven deaths as people tried to move on from Italy and five as people tried to cross from France to England. Thousands of others reported having been pushed back from one state or more, and sometimes subjected to violence.[79]

Measures to address onward movement must include further solidarity and support for countries where most refugees and asylum-seekers are located.[80] In particular, a mechanism is needed to relocate asylum-seekers from EU member states that receive a disproportionate number of asylum claims to other EU member states as part of the reform of the Dublin Regulation.[81] Until such a mechanism is in place, UNHCR encourages ad hoc arrangements, in line with existing EU law and frameworks, to foster responsibility-sharing. This would include relocation on a voluntary basis, and the use by EU member states of their discretionary powers under the Dublin Regulation. In the Balkans, several states need further support, including help developing their asylum systems and to negotiate readmission agreements when relevant.

Elsewhere, in situations where countries receive a high number of asylum applications as a result of mixed movements, UNHCR has recommended the use of accelerated and simplified procedures as a means to quickly process manifestly unfounded – as well as manifestly well-founded – applications with a view to assisting those found to be in need of international protection with their integration, and channelling those who are not into return procedures.[82]

In countries outside Europe where many refugees have initially fled, further solidarity is also needed in accordance with the newly-adopted Global Compact on Refugees. For example, in Ethiopia, a key refugee-hosting country and country of transit for some refugees who subsequently travel on to Europe via Libya, the government with support from the international community has pledged to provide work permits for refugees, increase the enrolment of refugee children in education, and expand the number of refugees allowed to live outside camps.[83] Further solidarity of this nature is critical to providing refugees with viable alternatives to dangerous journeys.

French village sets an example of how to welcome refugees

Mayor of Pessat-Villeneuve, Gerard Dubois, with Ramedan Ibrahim, an Eritrean refugee who was resettled from Niger (left) and Alfatih Sali Hadam, a Sudanese refugee who was resettled from Chad (right). © UNHCR/Benjamin Loyseau

By Céline Schmitt and Joséphine Lebas-Joly in Pessat-Villeneuve

It is nearly 5 pm on a cold January evening in Pessat-Villeneuve and the first snow of the year is falling. The atmosphere is quiet as a group of African refugees take a break from French classes.

It is an important day. In keeping with tradition, the mayor, Gérard Dubois will present his New Year wishes to villagers and their refugee guests at a reception in the evening.

Besides its 653 inhabitants, the village, in the Puy de Dôme region in central France, hosts 60 refugees resettled from Niger and Chad. They arrived four months ago and are accommodated in the village’s château.

Sudanese refugee Alfatih, 25, is one. He jokes outside the school, where he has been learning French for nearly four months.

“The first thing I noticed in Pessat-Villeneuve is that there are many good people here,” Alfatih says. “They help us a lot. Pessat-Villeneuve is nice.”

Just four months earlier, Alfatih was in Goz Beïda, in eastern Chad. He has never seen snow before and wonders how it feels.

In 2018, France undertook to resettle 3,000 refugees from Chad and Niger by the end of 2019, including some of those evacuated from Libya.

The refugees are accommodated in the château under the care of a local non-governmental organization, CeCler.

The NGO’s social workers and educators help them navigate administrative procedures, and find housing and work, while volunteers guide them through daily life, such as shopping and sports activities.

Alfatih fled Sudan when he was a child. He was 10 when the Janjawid militia attacked his village and killed his father in front of him.

“My father was at the mosque on a Friday,” he recalls. “My mother told me to run and to tell my father that the village was being attacked. In the panic, everyone ran in another direction and I couldn’t find anyone. When I returned home, I saw my father killed in front of me.”

During the attack, Alfatih was separated from his mother, brothers and sisters.

The group took him to the forest, where they beat him then abandoned him. “I cried a lot. I didn’t know what I could do.”

For months, he searched for his family from village to village without success. He found an uncle who took him under his wing and together they fled to Chad. There, they were taken to Goz Amer refugee camp by UNHCR, the UN refugee agency.

“When I arrived there, I was very, very tired of running,” he says. “I was very sad until I found my mother, my sisters and my brothers.”

Alfatih resumed his education and passed the Sudanese baccalaureate in Chad. He also took a course in agriculture.

More than once he thought of taking the dangerous road to Libya and discussed it with his friends, but stayed behind in Chad.

“My mother had an operation in Goz Beïda,” he says. “Her health is not good. Her heart is bad. Sometimes, she could be happy, sometimes, she could be ill. We don’t have a dad who can support us, who could help us, and we need to study.”

Alfatih was the only member of the family who had any vocational training but his prospects were poor and life was difficult.

“We could not return to Sudan. We said to each other that our only choice was to go to Libya and after that to try anything. We needed to study. We were in the camp for a long time.

“A lot of my friends went to Libya. I don’t know where they are now.”

The French government resettled Alfatih’s mother, his two younger brothers and sister in Dijon. Alfatih, another brother and sister were taken to Pessat-Villeneuve.

Resettlement is a way to protect the most vulnerable refugees and shield them from dangerous journeys.

Ibrahim, a 30-year-old refugee from Eritrea, also lives in the Pessat-Villeneuve reception centre. He was resettled from Niger to France after being evacuated from Libya by UNHCR.

Previously, he made five unsuccessful attempts to undertake the dangerous sea voyage from Libya to Europe. During one of the attempts, he was among the few who survived when their boat capsized.

“Out of 148 people, only 20 people survived,” he says. He and six others clung to a wooden section of the boat and managed to stay afloat.

In Pessat-Villeneuve, Alfatih and Ibrahim are taking intensive French classes, organized as part of their four months’ stay in the reception centre. They have made good progress, but they have found it difficult.

Now that they are safe, Alfatih and Ibrahim want to resume their studies.

Alfatih has ambitions to be become a doctor or a social worker so he can help others. Ibrahim wants to work in the food industry.

“I believe you can do anything if you really want to”, Alfatih says.

“In what I learn from life in France, what strikes me too, is that here, I live in a democracy.”

In a nearby classroom, Mayor Dubois is making the final preparations for the New Year ceremony and welcomes guests.

In his speech, he reviews the highlights of the year. With pride he mentions the opening of the refugee reception in the château.

“I will always be here to defend our village, its interests, its residents, its employees, its officials, its values,” he says. “I will be the shield against hared, xenophobia, populism and mediocrity.

“Friends, we are on Gallic soil. Before you enjoy the dishes made for you, I will pass on a secret recipe, the one for Pessat-Villeneuve’s magic potion. Although it’s a secret, I give you permission to share it with the whole world.

“You take one quarter liberty, one quarter equality and one quarter brotherhood. And you need a pinch of secularism. Mix in a good dose of optimism. Don’t forget to water it generously with mutual support.

“And there, before your eyes, is a commune like Pessat-Villeneuve, a place full of humanity and the qualities that together define us: free, fraternal, supportive and, quite simply, human”.

Children on the move

Swiftly identifying children separated from their families, who are at heightened risk, is essential to determining how best to protect and assist them. In 2018, many of those arriving in Europe were unaccompanied children. Some 3,500 unaccompanied children, primarily from Tunisia, Eritrea and Guinea, arrived by sea in Italy (around 15% of all arrivals).[84] In Greece, over 1,900 unaccompanied children arrived by sea with most from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Syria. As of the end of 2018, the arrival of more than 340 unaccompanied children under the age of 14 had been recorded in Greece.

Unaccompanied children often face greater dangers than adults as they travel from one country to the next. Tesfay, 17, from Eritrea was one of those evacuated from Libya to Niger. He told UNHCR:

I left Eritrea when I was very young – four years old, I think – with my mother. We went to Sudan for many years. But as we had no papers, we were illegal, so I couldn’t go to school. I worked as a cashier in a shop from when I was 12 years old.

I tried to leave Sudan in 2017, but I was caught and brought back by the police. But I tried again in 2018 and I succeeded. My cousin paid the $5,000 [the smugglers] demanded from me…but I still spent four months in detention in Libya.

In detention it was really tough. We never had enough to eat or to drink. We must have been around 500 or 600 people. There were people from many other African countries too, like Nigeria, Congo, Kenya and Mauritius. When we asked them for food, they would come and beat us. They robbed us of our money and our phones.

When we finally reached the sea shore, we were all arrested. We were taken to Gharyan [detention centre], and from there, UNHCR took us to Tripoli. I spent just one month in Tripoli before UNHCR helped to bring me here to Niger. When they told us we could come here, we didn’t really believe that we would really travel. Even on the bus to the airport, we still thought we would be kidnapped… We were very scared. We didn’t really believe it was true until we actually arrived in Niger.

Even here, we first thought that maybe the same thing might happen again. Now I just hope to go to Europe to help my family and maybe even to bring them there, especially my Mum.

In Greece, unaccompanied children, mostly from Pakistan and Afghanistan, were frequently among the arrivals at the land border, with smaller numbers arriving on the islands. Those arriving by sea on Lesvos, Samos and Chios islands, including particularly vulnerable children, would often remain for extended periods of time because of delayed administrative procedures,[85] and were accommodated in substandard shelter or put together with adults not related to them. The lack of adequate shelter and poor oversight of the children exposes them to serious risks, including sexual exploitation and abuse. Some children are reported to have spent more than a year in such conditions.[86] As of the end of 2018, of the 3,700 unaccompanied children in Greece, only one in three was in appropriate care arrangements, mainly in shelters. Nearly 750 unaccompanied children were homeless or missing.[87] UNHCR expressed concern about these conditions several times in 2018 and urged the Greek authorities to address them, in particular to accelerate transfers to the mainland.[88] On one of the islands, unaccompanied girls had to take turns to lie down due to overcrowding in the container to which they had been assigned. Going to the toilet required a police escort. Similarly, in the boys’ areas where 18 boys share each room, they also have to sleep in shifts on account of overcrowding. On another of the islands, 24 children share each small room. In this area, there are just six toilets and three showers for 250 people.

In Spain, unaccompanied children from Morocco, Guinea and Mali were frequently observed among the arrivals. Around 5,500 unaccompanied children are thought to have reached Spain in 2018. With the sudden increase in arrivals of all ages, reception conditions, including for unaccompanied children, were inadequate. Similar challenges were observed in Malta, where up to 20% of those arriving by sea in the latter half of 2018 were unaccompanied children. Children had to endure challenging reception conditions, with many sharing overcrowded accommodation with adults and being placed in detention-like facilities. Further measures are also needed to strengthen access to asylum procedures, including for children.

In the latter half of the year, most sea arrivals to Italy, including from Libya, were to Lampedusa. Although transfers of children from Lampedusa to the Italian mainland have been slightly accelerated, reception conditions in the hotspot continue to be unsuitable, in particular because of overcrowding on account of the centre’s reduced capacity. In addition, the separation of children from adults not related to them is not guaranteed. In 2018, 61% of the more than 8,500 unaccompanied children whose asylum applications had been processed were granted humanitarian protection in Italy. Thus the introduction of law number 132 in December 2018, which, among other things, introduces specific grounds for special protection but repeals humanitarian protection, may have a negative impact on children.

A boys stands in the reception and identification centre in Moria on the island of Lesvos, which in September 2018 hosted more than 8,500 asylum-seekers, almost four times its official capacity. © UNHCR/Daphne Tolis

In the second half of the year, an increased number of unaccompanied children arrived in Italy via the Western Balkans route. Most were nationals of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. As children crossed at many different points, targeted interventions and information provision were difficult and some tended to move quickly on to Italy’s western border with France in order to pursue their journey onwards. In France, the practices adopted at the border with Italy regarding children have been noted and the need to respect legal safeguards has been underlined by several actors.[89] In 2018, an increasing number of children were protected under the national child protection scheme. In December, UNHCR published a report based on interviews with unaccompanied and separated children that identified a number of issues to be followed up in the best interests of the child, highlighted best practices and made a number of recommendations. These include the need for additional reception facilities, better access to information and interpreters, and access to legal representation.[90]

In the Balkans, UNHCR and its partners in Serbia observed an increase in the number of unaccompanied children, mostly from Afghanistan, arriving in the second half of 2018. Most were understood to have entered the country from Bulgaria, along with others who had crossed from the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Many of the more than 1,500 unaccompanied children tried to travel on irregularly from Serbia, with only around 500 remaining in the country as of the end of the year. For those still in the country, Serbia has made improvements to three dedicated centres for unaccompanied children but, because of a lack of space, many others were accommodated together with adults in asylum centres, where more services for unaccompanied children are still required. On the other hand, with the support of UNHCR, the Serbian authorities strengthened the guardianship system by recruiting additional guardians; the latter were in daily contact with the unaccompanied children to whom they were assigned. In Albania, UNHCR and partners observed that most unaccompanied children identified were from Syria, followed by Pakistan, Algeria and Morocco. More dedicated centres for unaccompanied children in the country are needed.

The heightened vulnerability of unaccompanied children on the move or hoping to move on irregularly saw many engaged in highly risky activities including sexual exploitation, sometimes as a means of earning money to pay smugglers, as well as using dangerous methods to try to cross borders such as trying to hide under vehicles in port areas.

UNHCR continues to call for an end to children being detained for immigration purposes, and for strengthened protection mechanisms for children, including by integrating unaccompanied and separated asylum-seeking children within national child protection systems with systematic oversight through guardianship and social work systems. For unaccompanied children in countries along common routes towards Europe, more needs to be done to facilitate access to family reunification and restore family links. More accessible information must be made available to children regarding their rights and obligations, the available services and support, and asylum processes. This is critical to reducing the risks children face because their vulnerability to exploitation, as well as to the dangers involved in onward movement with the use of smugglers or traffickers.

Eritrean kids reunited with mom after eight-year odyssey

Eritrean kids reunited with mother after 8 years separated

By Tarik Argaz in Tripoli, Libya

Kedija, 15, and Yonas, 12, survived kidnapping, detention, and a failed sea crossing before finally rejoining their mother in Switzerland.

Two months ago, as they languished in a detention centre in the Libyan city of Misrata, Kedija* and her brother Yonas’s epic attempt to reunite with their mother in Switzerland after eight years of separation appeared doomed.

Up to that point, the siblings from Eritrea – aged just 15 and 12 – had fled their homeland, survived alone in an Ethiopian refugee camp, been held for ransom by kidnappers, and finally made it aboard a vessel heading across the Mediterranean to Europe, only to be intercepted and returned to Libya.

But thanks to the doggedness of their mother Semira, the intervention of governments and humanitarian agencies, and a large slice of luck, two months later the children are sitting in Switzerland in their mother’s arms once more.

“Despite being separated for more than eight years, I never lost hope of being reunited with my kids again,” said Semira, gripping them tightly as if they might still disappear, with tears of joy and relief running down her smiling face.

For UNHCR it all began with a phone call to staff in Libya from the International Social Service – a Swiss-based NGO specialized in child protection issues – whom Semira had contacted for help.

Knowing only that the children were being held somewhere in the country, and with just their names and an out of date photo to identify them by, UNHCR staff and their NGO partners in Libya began scouring every detention centre they had access to.

But with an estimated 5,700 refugees and asylum seekers currently being held in dozens of official detention centres across the country, and others falling into the hands of armed groups and human traffickers, the chances of finding them were slim.

When Senior Protection Assistant Noor Elshin came across two skinny and pale children in Misrata’s Karareem detention centre, they looked so unlike the happy and healthy faces in the photo that staff had been given that it was a shock to learn that he had indeed found Kedija and Yonas.

“This is literally like finding a needle in a haystack,” Noor said. “Despite having them in front of me, I still couldn’t believe that we’d actually found them.” Shortly afterwards, Semira received the call that she had been praying for – her children had been found.

The family’s odyssey began in 2010, when Semira was forced to flee persecution in Eritrea. Rather than drag her children into the unknown, she took the difficult decision to leave them with their grandparents while she sought a safe refuge for the family.

After five years of relative stability, in 2015 Kedija and Yonas were themselves forced to flee insecurity in Eritrea and cross the border into Ethiopia. Semira lost contact with them for several months while her brother, who was also in Ethiopia, desperately searched for his niece and nephew.

He eventually found them living alone in a refugee camp near the Ethiopia-Eritrea border, and pledged to do all he could to reunite them with their mother, who by now was living in Switzerland.

In mid-2017, the children and their uncle set off on their perilous and uncertain journey to reach Semira. The trio battled fierce temperatures, thirst and hunger as they begged rides on trucks and buses across Ethiopia and Sudan, striving to reach the southern shores of the Mediterranean Sea.

But events took a dark turn at the Sudanese-Libyan border, where the group were violently abducted by smugglers, who found out the children’s mother was living in Switzerland and demanded a ransom in order to free them.

When Semira was unable to meet the criminals’ financial demands, Kedija and Yonas were separated from their uncle – whom they never saw again – before being sold on from one smuggler to another, terrified and more vulnerable than ever.

Then one day, several weeks into their ordeal, the siblings were unexpectedly released and left to wander lost and alone in the vast Libyan wilderness. Miraculously, they were discovered and taken in by a group of fellow Eritreans, who were also planning to take a boat to Europe and promised to bring them along.

When the boat was intercepted and the children returned to Libya and detained, they were able to phone their mother, who by this time was frantic with worry. “I’d spent days and nights praying for them, despite everyone around me losing hope, until the day I heard my daughter’s voice for the first time in several months,” Semira recalled.

After the children were found, the Swiss government agreed to grant them humanitarian visas to join their mother.

On the morning that UNHCR staff entered the detention centre to take the children on their final journey back to their mother, their story was well known to everyone inside. They left the centre with the joyful singing and chanting of their fellow Eritrean detainees ringing in their ears.

Less than 24 hours later, after an overnight stay in Tunis where the Swiss embassy provided them with their travel documents, Kedija and Yonas touched down in Switzerland where an anxious and excited Semira was waiting for them.

Catching the first sight of her tired and disoriented children in the airport arrivals gate, eight years of worry and longing fell away as she ran to them and buried herself in their ecstatic embraces; safe, happy and reunited at last.

*All names have been changed for protection purposes

Limited access to safe and legal pathways

In light of continued displacement in neighbouring regions as well as gaps in the protection available to refugees in some of the countries through which they often move, more still needs to be done to support first host countries and ensure that more people can benefit from safe and legal pathways to protection.

Resettlement remains a primary legal avenue for refugees and in 2018, the number of refugees resettled to Europe decreased slightly from almost 27,500 in 2017[91] to 24,185 as of the end of November.[92] The UK, Sweden, France, Germany, and Norway resettled most refugees with Syrians constituting by far the largest group being resettled from Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt. Nationals of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea and Sudan were the next largest groups to be resettled. Following UNHCR’s call in September 2017 for 40,000 additional resettlement places for refugees in 15 priority countries along the Central Mediterranean route,[93] resettlement countries have pledged 39,698 places, of which 14,450 places were pledged by European countries. As of the end of November 2018, 10,182 of these refugees have already been resettled.

Because of the many dangers facing refugees in Libya,[94] UNHCR has established the Emergency Transit Mechanism (ETM) jointly with the government of Niger. This is a mechanism through which refugees evacuated from Libya may be temporarily hosted in the country until they can be resettled elsewhere. Several European states, including Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK, as well as Canada have committed to providing resettlement places and received resettled refugees evacuated from detention centres in Libya to Niger via the ETM. Some 2,879 refugees have been evacuated from Libya since the start of the programme. In 2018, Italy also evacuated 253 directly from Libya. UNHCR is appreciative that resettlement states have pledged to providing a total of 5,456 resettlement places so far, but more commitments are still needed.

Refugees hoping to be reunited with family members in Europe continued to face significant obstacles last year that kept many of them apart. These obstacles included restrictive definitions of family applied by some states, difficulties gaining access to the relevant embassies in order to apply, a lack of access to the documentation required to prove family links, the high costs involved in the process, and delayed or more limited access to family reunification for beneficiaries of subsidiary protection.[95] Some positive developments were also noted in 2018, such as Germany opening new service centres in key countries where refugees live, including Egypt, Kenya, and Ethiopia, in order to assist refugees’ family members with their applications for family reunification.

The positive use of humanitarian visas by some European countries continued in 2018 including through programmes established jointly between faith-based organizations and the Belgian, French and Italian governments. These facilitated the arrival of many Syrian, Eritrean and Ethiopian nationals.

UNHCR encourages states to continue to expand opportunities for refugees and their families to travel safely and legally in order to find protection.

An Eritrean couple and their newborn baby wait at UNHCR’s Gathering and Departure Facility in Tripoli in December 2018 before being evacuated to Niger. © UNHCR/Farah Harwida

Sources

[1] In general, most displaced people flee to another part of their country or cross borders but stay within the region.

[2] International protection includes those granted refugee status or subsidiary protection.

[3] This is based on Eurostat data for the EU member states along with Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland on the international protection rates for Q1-3 in 2018 for the top 10 nationalities arriving via each route in 2018 according to the proportion of those nationalities amongst arrivals. The top 10 nationalities arriving via the Eastern Mediterranean sea route to Greece accounted for 91% of all sea arrivals there; the top 10 via the Central Mediterranean route (Italy and Malta) accounted for 78% of all arrivals there; and the top 10 via the Western Mediterranean route accounted for 89% of all arrivals there.

[4] The number of sea arrivals in Spain from March onwards (excluding arrivals from Libya) were as follows: March – 900; April – 1,200; May – 3,500; June – 6,300; July – 8,600; August – 6,300; September – 8,100; October – 10,200; November – 5,000; and December – 4,800.

[5] The increase in arrivals to Spain appears to be a combination of several factors, including increasing opportunities created by smugglers, the pull factor created by the success of others, a need for international protection and/or family reunification for some, the difficulties crossing from Libya to Europe, and the roundups and deportations in Algeria. See also Mixed Migration Centre, The “Shift” to the Western Mediterranean Migration Route: Myth or Reality? 22 August 2018, http://www.mixedmigration.org/articles/shift-to-the-western-mediterranean-migration-route/

[6] In 2018, as outlined later in the report, many of those arriving by sea in Spain did not apply for asylum. While in many cases this appears to be a deliberate choice, lack of information on the process and long waits for asylum application appointments are other contributing factors.

[7] In 2018, 777 people were believed to have died during attempts to cross the sea to Spain compared to 202 deaths in 2017. In addition, the number of deaths in relation to the number of arrivals by sea to Spain also increased from one death for every 109 persons that crossed the sea in 2017 to one death for every 74 arrivals in 2018.

[8] In 2018, some smugglers are reported to have adopted a new approach in which people pay their money to a middleman and only transfer it to the smuggler upon arrival in Spain. These smugglers stand to lose out on their fees if the boat is intercepted so some are believed to encourage departures in poor weather to avoid surveillance. See I. Alexander, Forty-seven people died crossing the Mediterranean in a wooden boat last month. This is their story, 15 March 2018, https://gpinvestigations.pri.org/forty-seven-people-died-crossing-the-mediterranean-in-a-wooden-boat-last-month-4c1a55d0f36e

[9] This was confirmed by the International Maritime Organization at the end of June.

[10] In contrast, in the first half of 2017, many rescues took place soon after boats had crossed into international waters from 12 miles from the Libyan coast onwards.

[11] Prior to August, the only other group to arrive directly in Lampedusa from Libya since October 2013 is believed to be a group of five people in September 2017. In Malta, the last boat to arrive directly from Libya was in 2015. In addition, in 2018, Tunisian authorities rescued two groups of 70 people in total that had departed from Libya, another group of 40 was disembarked in Tunisia after being rescued by a merchant vessel, and 12 people were evacuated to Tunisia after being rescued by Italian authorities in international waters.

[12] For example, a group of 264 people that arrived in Pozzallo, Italy in November on a large wooden boat reported having been without food and water for three days prior to their arrival.

[13] An updated position issued by UNHCR in September notes that “UNHCR does not consider that Libya meets the criteria for being designated as a place of safety for the purpose of disembarkation following rescue at sea”, see UNHCR, UNHCR Position on Returns to Libya – Update II, September 2018, https://www.refworld.org/docid/5b8d02314.html, page 22.

[14] Between June and December 2018, at least 21 different groups that had been rescued at sea waited at sea for five days or more while permission was sought for the rescuing vessel to access a safe port for disembarkation. Following Italy’s decision to not allow disembarkation of all persons rescued off the Libyan coast at its ports, of the over 1,500 persons subsequently rescued by NGOs until the end of the year, 72% were disembarked in Spain and 28% in Malta. In addition, Italy permitted the disembarkation of two merchant ships (one Italian-flagged) with a total of 180 persons as well as one EUNAVFOR Med vessel with 106 persons, and Malta permitted the disembarkation of 12 persons from a Spanish fishing vessel.

[15] The Danish-flagged Alexander Maersk was only granted disembarkation permission in Italy in June after a delay during which it was moored off the Sicilian coast. In July, there was a delay of several days before an Italian Coast Guard vessel was sent to transfer persons rescued off the Libyan coast by an Italian-flagged merchant vessel, VOS Thalassa.

[16] Periods in detention in Malta prior to transfers ranged from just over a week to more than three months.

[17] An estimated 2,872 deaths occurred at sea along the Central Mediterranean route in 2017 compared to an estimated 1,312 in 2018.

[18] In contrast, in June 2017, there was one death for every 54 persons who arrived in Europe after departing from Libya. In June 2017, 22,156 people arrived in Europe from Libya and 412 died at sea.

[19] The rate of deaths for the Central Mediterranean route in 2018, including arrivals to Europe of people who departed from Algeria, Greece, Libya, Tunisia, and Turkey was one death for every 20 arrivals in Europe, compared to one death for every 42 arrivals in 2017.

[20] See UNHCR, UNHCR Position on Returns to Libya – Update II, September 2018, https://www.refworld.org/docid/5b8d02314.html

[21] While the number of persons granted entry had been reduced in 2017 from up to 100 people per week at the start of the year to 50 per week by the end of the year, as of the end of 2018, the number granted entry per week was 10.

[22] Most Syrians in Cyprus are granted subsidiary protection instead of refugee status according to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, which results in them not being entitled to family reunification according to Cypriot law, which would enable close family members to travel safely and legally. Family reunification is available for those granted refugee status.