More than two years after the Global Compact’s call for more data and evidence on forced displacement, progress has been made. What are some of the trends in the emerging research?

Bangladesh. Covid-19 awareness and response program in the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar. © UNHCR/Amos Halder

—

Much has been made about the need for better data and evidence on forced displacement. In the words of the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR),

“Reliable, comparable, and timely data is critical for evidence-based measures to: improve socioeconomic conditions for refugees and host communities; assess and address the impact of large refugee populations on host countries in emergency and protracted situations; and identify and plan appropriate solutions.” (Section 3.3, GCR, Dec. 2018)

The World Bank report Fragility and Conflict: On the Front Lines of the Fight against Poverty underscores the vast scale of the gap in comparable data when it comes to forcibly displaced persons: they are among the 500 million people who live in fragile and conflict-affected states with no or outdated information on poverty levels.

This lack of data is consequential: over the last year, it limited early efforts to anticipate the socioeconomic impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on refugees. Researchers were only able to compile comparable, representative datasets for slightly more than one-third of the global refugee population living in emerging market and developing economies.

Motivated by the GCR, new investments are bringing the promise of more data, including through efforts of the World Bank – UNHCR Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement (JDC), national statistical offices, and academic economists and researchers. What sort of additional evidence might we expect to see that is useful for programming, policy and advocacy? And what gaps remain?

Early initiatives of the JDC, including a Forced Displacement Literature Review and research conference series hosted with leading universities, as well as the Global Compact Academic Interdisciplinary Network, provide some insight to this question.

Literature review shows growing body of work on diverse themes

The JDC literature review highlights recent publications, academic scholarship and thought leadership on issues relating to forced displacement with the intention of encouraging the exchange of ideas.

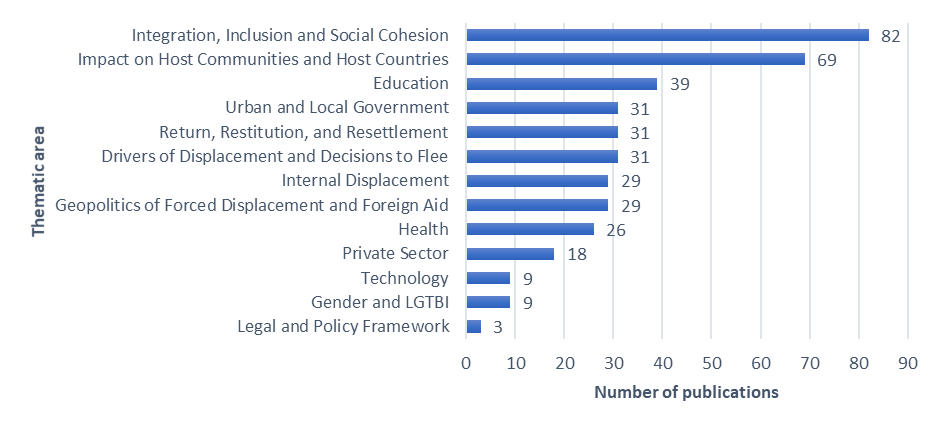

While not intended as a scientific survey nor an endorsement of the cited works, with over 405 citations as of June 2021, it does indicate some trends in this growing body of work. Publications – many of which focus on quantitative, socioeconomic studies from low- and middle-income settings – are organized into 13 thematic areas (Figure 1). The largest number of publications fall under the chapters dedicated to “integration, inclusion and social cohesion” (82 publications), “impact on host communities and host countries” (69) and education (39). Over the course of the last year, studies on health have doubled, with many more certain to come as efforts continue to understand and address the impacts of COVID-19.

Figure 1: Number of publications, by thematic area

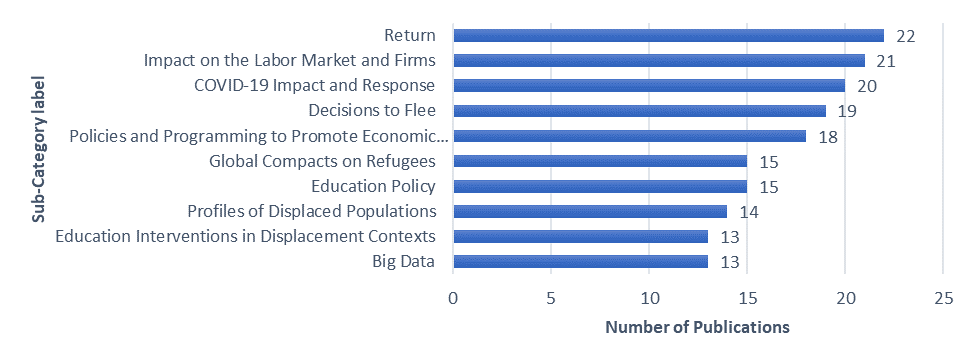

Publications are also classified into one or more of 66 sub-categories, offering additional nuance and insight into emerging trends. The most common sub-categories cover a range of topics across the displacement lifecycle, from decisions to flee to return to country or area of origin (Figure 2). In between, considerable analytical work at the country level is being carried out to understand and facilitate economic inclusion through labour market policy and programmes. Of the sectoral topics, education has attracted significant interest, while work on the health and socioeconomic impacts and response to the pandemic also feature frequently. Finally, big data tools and methodologies are also increasingly used in a range of publications across thematic areas.

Figure 2: Number of publications, by most common sub-categories

But geographical coverage is more limited and there are significant knowledge gaps in countries that produce or host large populations of forcibly displaced persons

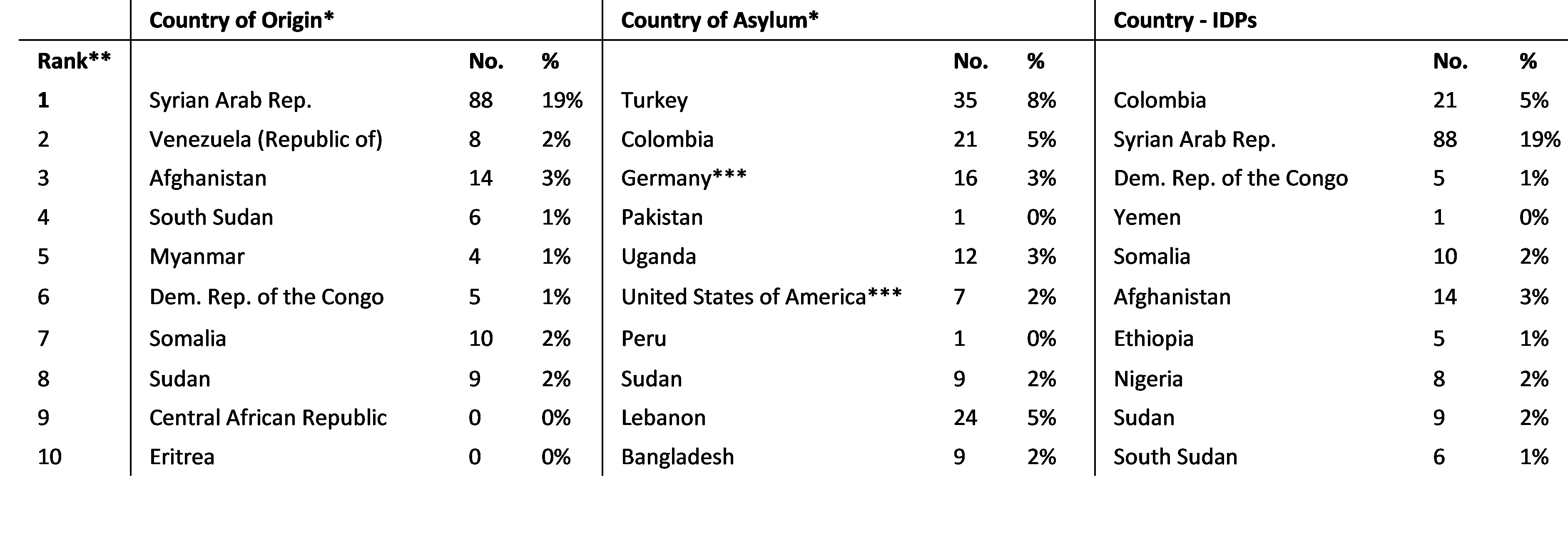

While diverse in thematic areas and sub-categories, only 10 countries make up nearly one-half of those cited in the literature review. One-third focus on Jordan, Lebanon, Syria or Turkey alone. One-sixth address Afghanistan, Colombia, Germany, Kenya, Iraq or Uganda, while another sixth are multi-country or global in nature. This suggests knowledge gaps in other countries that produce or host large numbers of forcibly displaced persons.

Aside from Afghanistan and Syria, comparatively little is written about many of the world’s most significant countries of origin. Among large countries of asylum, Pakistan and Peru feature in a single publication each, while Democratic Republic of Congo and Yemen are less studied despite being home to large numbers of internally displaced persons. A handful of countries – Democratic Republic of the Congo again, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan among them – feature as both producers and hosts of refugees, as well as internally displaced persons, lending particular urgency to the need for stepped-up efforts to produce and expand knowledge in areas of prevention and solutions.

Some of these trends are due to the scope of the review, with its focus on low- and middle- income countries and publications in English (itself commonly observed in economics). Other reasons certainly include access of humanitarian and development agencies, rapidly changing conditions and conflict. Nevertheless, it does raise questions about the marginal benefits of new studies: motivating research in situations currently underrepresented in the literature, and the rich networks of collaboration that produce it, could be life changing for forcibly displaced persons through more evidence-based support and service delivery.

Table 1: Number of publications, by displacement type and country

In this regard, ensuring the availability of reliable, comparable data on these situations is one way to help overcome research barriers. Ongoing work by the JDC, UNHCR, the World Bank and national statistical offices to expand survey work into new locations is vital to doing just that.

Bridging the gap between research and action

The approaching inaugural High Level Officials Meeting in December, organized between the biennial Global Refugee Forums, provides an opportunity to reflect on where we stand in the Global Compact’s call for more and better data and evidence.

As more data leads to more evidence, the logical next question is: how do we bridge the gap between research and action to inform programming, policy and advocacy that improve the lives of the displaced and their hosts? Answers to this are emerging, with UNHCR operations expanding their use of evidence through a range of actions from improved targeting of assistance to tracking of inclusion efforts, and will only become more relevant and vital in the months and years to come.

—

Note: * Refugees, asylum seekers and Venezuelans displaced abroad; ** Based on UNHCR Population Statistics, as of June 2021. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/; *** Review focuses primarily on low- and middle- income countries