by Ibrahima Sarr, Theresa Beltramo and Craig Loschmann

COVID-19 has complicated responses to forced displacement and placed additional burdens on host governments and stakeholders in low- and middle-income countries where most refugees live. The measures to stop the spread of the virus are believed to disproportionally affect forcibly displaced persons.

Studies by the Center for Global Development and the Norwegian Refugee Council show that the effects of the pandemic on forcibly displaced persons are likely exacerbated by their limited access to formal labour markets and social protection in most countries. These factors contribute to loss of employment and income and as a result an increase in poverty.

COVID-19 hit Kenya harder than most African countries, according to September 2021 data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. The pandemic resulted in widespread lockdowns, including movement restrictions in and out of all camps and settlements hosting refugees. As of the time of writing these remain in place, resulting in limited access to refugee camps.

Using socioeconomic data originating from five waves of high-frequency phone surveys conducted over May 2020 and June 2021 as well as other household surveys, we examine the impact of COVID-19 on in-camp as well as urban-based refugees in Kenya.[1] While not exhaustive, the aim is to provide evidence of how forcibly displaced persons are coping during the pandemic compared to Kenyan nationals, and inform the design of action to support both groups. The surveys focused on indicators related to mental health, livelihoods and access to services – programmatic priorities identified by UNHCR and our operational partners.

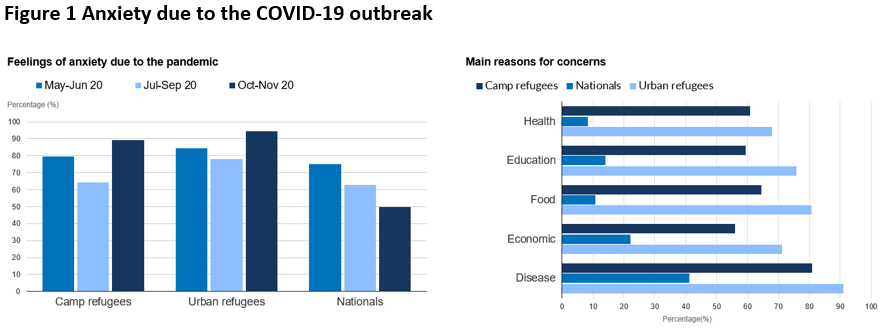

Refugees consistently reported higher levels of anxiety as a result of the pandemic compared to Kenyan nationals and their anxiety levels rose in Q4 2020 while nationals anxiety fell over the same time period. During the July-September 2020 period, 95% of refugees living in urban areas reported pandemic-associated anxiety (Figure 1). When asked, all three groups in Wave 1 (July-September 2020) emphasized the risk of infection either to themselves or others in the community as their main worry.

While concerns regarding risk of infection continued over time, the economic concerns arising from loss of employment, economic downturn and restricted movement rose dramatically for refugees from Wave 1 to Wave 3. By October-November 2020, 56% of in-camp refugees and 71% of urban refugees reported having economic concerns, whereas that figure is one-fifth for the national population.

Note: Information on anxiety level was captured only in Waves 1-3.

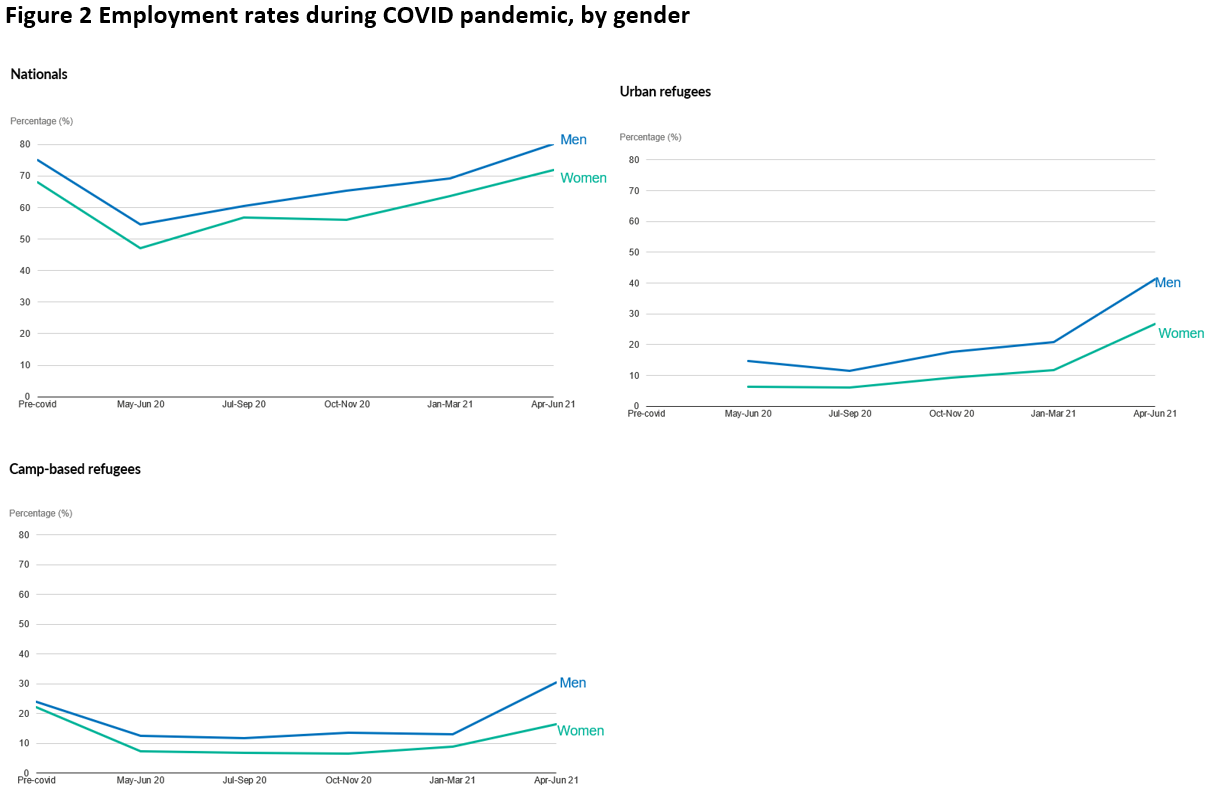

Employment declined sharply in the early months of the pandemic. It has recovered to pre-pandemic levels but at a slower rate for refugees. In the early months of the pandemic, the results of the phone survey indicated a steep drop in work opportunities for both refugees in camps and Kenyan nationals. Pre-COVID, 25% of the refugees in camps were employed compared to 71% of nationals. By May-June 2020, refugee employment fell to 10% and remained at that level until January-March 2021. A year into the pandemic (April-June 2021), employment seems to have recovered back to 24% for refugees and 76% for hosts.

Women refugees are falling behind on employment. In April-June 2021, the employment rate for male refugees in camp surpassed its pre-crisis level (24% pre-COVID versus 30% in April-June 2021), while that for women stayed below its pre-COVID level (22% pre-COVID versus 17% in April-June 2021, Figure 2). The drop in women’s employment due to the pandemic puts at risk progress towards gender equality observed over the past 15 years.

Women suffer disproportionately more when it comes to job and income losses chiefly due to their over-representation in the hardest-hit sectors (ILO, 2021). Moreover, when countries begin to recover from the crisis, women may face barriers to finding jobs due to mobility constraints, care responsibilities and lack of information (Papa A. Seck et al, 2021). It will take deliberate, targeted action by humanitarian and development actors to enable the participation of women and other vulnerable groups in the overall recovery from the pandemic.

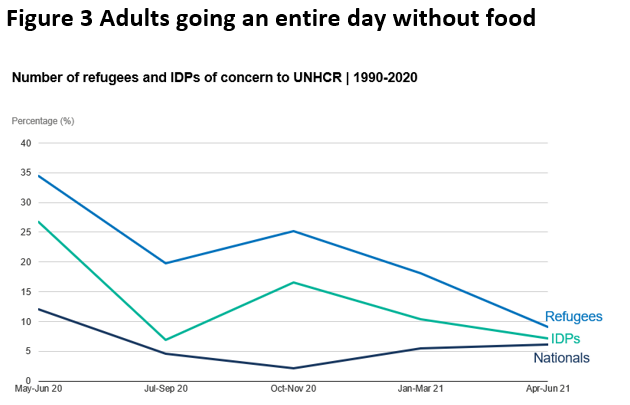

Refugees and host communities alike resorted to reducing their food consumption to cope with income losses, with camp-based refugees reporting the highest food insecurity. The reduced income as a result of lost employment puts vulnerable groups at further risk of impoverishment. Food insecurity was alarmingly high in the early months, especially among urban refugees, but has since improved. In the early months of the pandemic, a more significant percentage of refugee households reported having an adult who spent an entire day without eating than national households (34% for camp-based refugees, 27% for urban refugees, 12% for nationals).

Since the start of 2021, the situation has improved, especially for refugee households. In April-June 2021, just 9% and 7% of camp-based and urban refugee households reported severe food security, respectively. For the same period, 6% of national households reported severe food insecurity (Figure 3).

Results from the high frequency phone surveys in Kenya show refugees are disproportionately affected by the crisis compared to nationals. Refugees report higher anxiety of risk of infection to COVID than nationals, they experience a longer depression in employment than nationals, and women refugees in camps employment levels remain lower than pre-COVID.

This work underscores the fundamental need for timely socioeconomic data in displaced settings to fully understand the conditions of persons under UNHCR protection and how they compare with the national population. These efforts have taken on greater urgency during the global recession associated with COVID-19, with UNHCR and the World Bank collaborating through the World Bank UNHCR Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement to include refugees in the World Bank High-Frequency Mobile Phone Surveys of Households to Assess the Impacts of COVID-19. As of Q1 2021, a total of 12 countries either have completed or are in the process of collecting comparable data among both refugee and host populations, with more countries planned for throughout 2021.

[1] In addition, where possible, the analysis relies on household surveys conducted by the World Bank and UNHCR in collaboration with Kenya National Bureau of Statistics before the COVID-19 pandemic among the same refugee populations residing in Kalobeyei and Kakuma camps.