By UNESCO EME, UNHCR, and UNICEF Innocenti Global Office of Research and Foresight

There are an estimated 12.5 million refugee children worldwide – a significant increase of 116% between 2010 and 2020. Of these children, close to half are estimated to be out of school, with data on refugee youth (aged 18-25) being largely unavailable. With the average length of displacement ranging from 10 to over 20 years, there is an urgent need to protect and serve these children by including them in national education systems.

UNHCR, UNICEF Innocenti Global Office of Research and Foresight, and UNESCO’s Section for Migration, Displacement, Emergencies and Education (EME) are working on several complementary research initiatives to better enable the inclusion of refugee learners into national education systems.

This collaborative effort is a central part of Education Strategy 2030, a high-level initiative to ensure refugees are accounted for in education sector planning and action, including through addressing the specific learning needs of refugee and host community students. Further, this engagement is critical in ensuring the inclusion of vulnerable populations, an aim closely aligned with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development goal to ‘leave no one behind’ in education systems.

Our work, summarized in this brief, examines current practices, key barriers and enablers associated with the inclusion of refugees and displaced learners in a few select countries.

In this post, we focus on one important dimension of this research – inclusive education data systems for refugee learners – and share an overview of research findings and recommended next steps.

What are inclusive education systems?

In inclusive education systems, refugees are fully embedded in the host country education system, and therefore face similar cost drivers, efficiency and quality constraints as host communities. Inclusive means “no better, no worse” in terms of teacher quality, school infrastructure, financing, access to learning materials and other resources for refugees as compared to host communities.

Inclusive refugee education data systems and policies

The Inclusive Data Charter by the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data articulates five principles that provide a helpful framework for defining the inclusion of refugee education data. They include making all populations visible in data and promoting data disaggregation.

In practical terms, it means that refugees are included in the sampling frames of data collection exercises and can be reliably identified once they are included. It also includes monitoring their progress in areas such as their learning and safety in line with SDG 4 and the Global Framework for Refugee Education.

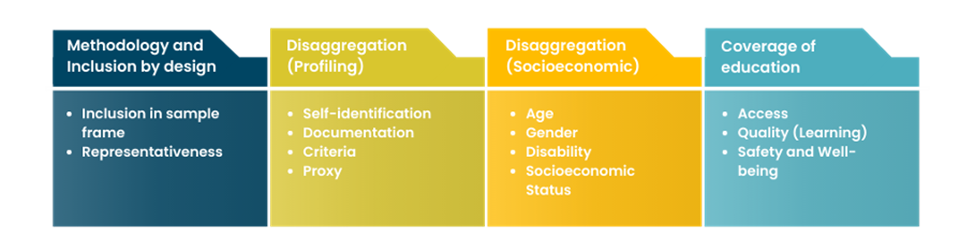

Figure 1: Framework for assessing the inclusion of refugees in education data systems

Inclusion in education systems refers to the entire education data ecosystem, from data collected by humanitarian actors to household censuses to education management information systems (EMIS) and other administrative data. This range of data sources is important as the provision of data on refugee education depends on factors ranging from national capacity to the scale and timing of the crisis.

Including and identifying refugees in national education data systems is important for individual refugees and for education systems. For refugees, having an educational ‘identity number’ facilitates recognition of their educational achievements and the transfer of educational certificates. For schools and education systems, data on refugee learners helps to identify and respond to their needs, and to measure and monitor education outcomes for different groups of children over time.

What has our research found?

Previous work by UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), UNHCR and the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) identifies key challenges relating to education data for forcibly displaced populations. They include non-inclusion of refugees in data collection samples, absence of disaggregation by migration status, and over-emphasis on data related to access to education and excluding others learning and dropout.

UNHCR, UNICEF and UNESCO’s work confirm these findings, showing that data on access is most common – even if still patchy in many contexts – while data on learning and school safety is very limited.

Further, the inclusion of refugees and forcibly displaced learners varies significantly across contexts, from almost no data being collected on refugee education in some countries to full data disaggregation by nationality or protection status in others.

A study commissioned by UNHCR found that in Chad, Cameroon and Mauritania, the lack of functioning national Education Management Information Systems (EMIS) impedes efforts to meaningfully monitor refugee education outcomes. Data on refugees is instead collected by UNHCR or its implementing partners, such as in Cameroon, where data collection in schools hosting refugee students is paper based, conducted by implementing partners, and consolidated by the UNHCR country operation.

In contrast, forcibly displaced learners in Latin America are included in national education data systems, as explored in UNESCO’s work. For instance, in Colombia, Peru and Ecuador, the education ministries collect data on enrolment of migrants and can disaggregate these figures by nationality. Factors that have enabled better visibility and inclusion (to different degrees) of Venezuelans within the education data systems in these countries includes donor prioritization of data on migrant and refugee education and the collection of data on student nationality through unique identification codes in the host country’s national EMIS.

UNICEF’s forthcoming report on educational inclusion includes a global review of good practices for refugee inclusion in national EMIS around the world, as summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of approaches to refugee inclusion in EMIS

| Approach | Example |

| Disaggregating school censuses, national EMIS, or national learning assessments by students’ refugee status or country of origin to facilitate measurement of learning outcomes for different groups | Colombia, Ecuador, Peru (UNHCR and UNESCO- UIS, 2021); South Sudan, Zambia (UNESCO, 2019a) Jordan (Jordan Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, 2018); Chad |

| Collecting data on refugee enrolment in annual statistical yearbooks | Ethiopia, Rwanda |

| Merging of UNHCR data with national EMIS data to identify most vulnerable schools and target resources accordingly; transitioning parallel EMIS into national system | South Sudan (UNESCO, 2019a) Türkiye (UNHCR and UNESCO-UIS, 2021) |

Challenges and gaps

Even where there is the disaggregation of refugees in national data education data systems, our research finds this remains focused on access, generally defined as the number of refugee or other forcibly displaced children that are enrolled in school. Although most countries have some form of national learning assessment covering at least one level of education, it is rarely possible to disaggregate this data by protection status (or a suitable proxy) to enable a comparison of outcomes between refugees and host country students. In general, research indicates that inclusion in national educational data systems lags policy change, use of host country curricula or access to certification.

What are the recommended next steps?

Following the principles of the Inclusive Data Charter, the following areas of research and practice are important to address existing data gaps and inform efforts to increase the educational inclusion of refugees:

Principle 1 – All populations must be included in the data

- Where data is already collected in national data collection exercises, there is a need to advocate for the inclusion of refugees in samples.

- Piloting a refugee module for school censuses for key refugee-hosting areas is a first step to increasing data inclusion.

Principle 2 – All data should, wherever possible, be disaggregated in order to accurately describe all populations

- The disaggregation of data by nationality (when it is a useful proxy for protection status) or by international protection status is an additional way to address data gaps on learning.

Principle 3 – Data should be drawn from all available sources

- Explore opportunities to engage with regional and international assessments to ensure sample sizes are representative of forcibly displaced learners in assessment design, analyses and reporting. (Regional assessments include ERCE in Latin America and the Caribbean, PASEC in West and Central Africa while the PISA is an example of an international assessment).

Principle 4 – Those responsible for the collection of data and production of statistics must be accountable

- Data production should be centred around the data user and utility to ensure resources are channeled and data is accessible in user-friendly formats to inform timely decision-making.

Principle 5 – Capacity to collect, analyze, and use disaggregated data must be improved, including through adequate and sustainable financing

- Promote the inclusion of refugees in data systems at national, regional and international levels by providing adequate and stable support for host country data collection and analysis of information related to refugee learners. This represents a key component of promoting inclusive rather than parallel educational provision for refugees.