By Theresa Beltramo, Masud Rahman, Ibrahima Sarr, Florence Nimoh

It is a well-established fact that women and girls globally face inequity when compared to men and boys in terms of enjoyment of rights and even basic choices over their bodies and fate. According to the UN SDG Goal 5 aimed at achieving gender equity, 750 million women and girls around the world were married before the age of 18 and at least 200 million women and girls in 30 countries have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM). In 18 countries, husbands can legally prevent their wives from working; in 39 countries, daughters and sons do not have equal inheritance rights; and 49 countries lack laws protecting women from domestic violence (UN SDG, 2021).

More than a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, evidence shows pre-existing inequalities are deepening, exposing vulnerabilities in social, political and economic systems for women and girls globally. Women on average play a disproportionately larger role in domestic responsibilities (including child rearing) when compared to their male counterparts and this is particularly salient for disenfranchised and poor women.

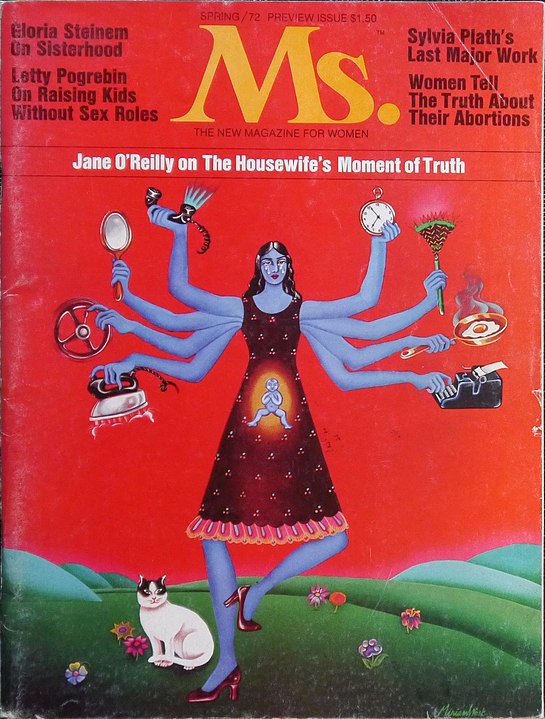

In addition to taking on the bulk of household responsibilities, women and girls provide essential income for the family, resulting in a tremendous amount of multi-tasking. An image that is conjured well in the original Ms. Magazine cover showing a pregnant version of the Hindu Goddess Kali with eight arms to hold a clock, skillet, typewriter, rake, mirror, telephone, steering wheel, and an iron. A recent report by UN Women finds that compounded economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are felt especially harder by women and girls who are generally earning less, saving less, and holding insecure jobs or living close to poverty. At the same time, their roles in unpaid care work has increased, with children out-of-school and older persons requiring heightened care (UN Women, 2020).

Women’s inherent fragility in terms of the enjoyment of basic rights and equitable welfare outcomes carries over into forcibly displaced settings. Among refugees, who as a group are more fragile than other poor people, women and girls experience hardships associated with forced displacement to deeper degrees. Recent evidence we are collecting with partners highlights the challenges faced by refugee women and girls as well as those in the immediate host community.

In Bangladesh, Cox’s Bazar refugee camps are home to 871,924 Rohingya refugees (UNHCR, 2021). Evidence from a recent brief authored by GAGE and UNHCR—Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on Rohingya and Bangladeshi adolescents in Cox’s Bazar—showcase the striking differences in the educational outcomes of girls and boys. Although Rohingya girls are disadvantaged irrespective of age, the inequity in learning intensifies as they age through adolescence. In the older cohort (equivalent to ages 15 to 19 years), only 5% of girls are enrolled in schools compared to 25% of boys. In the young cohort (equivalent to ages 10 to 14 years), they are a little over half as likely to be enrolled (33% versus 51%). In addition, across both refugee and host communities in Bangladesh, we find that 8% of adolescents reported an increase in gender-based violence (GBV) in the community during the pandemic.

In Uganda, we analyze comparable socioeconomic data produced by the World Bank and the Uganda Bureau of Statistics in 2018, and find that refugees with higher levels of education have more successful outcomes in the labour market (UNHCR, Uganda Bureau of Statistics and World Bank, 2021). Yet male refugees are nearly twice as likely to complete secondary education than female refugees (11% for males versus 6% for females), leading to lower overall lifetime earnings for women and girl refugees. Before COVID, both female and male-headed households were equally likely to be poor. Since the COVID outbreak, members of female-headed households were significantly more likely to have gone a full day without eating. Female-headed households also reported lower access to main staple foods compared to male-headed households in December 2020 (55% versus 68%) (WB, UNHCR, UBOS, 2021). This can have a disproportionate impact on children’s overall development as more than half of camp-based refugee households are headed by women.

These sobering statistics serve as a reminder to the global community that targeting gender-based inequity and vulnerabilities should always be a programmatic priority.

In Kenya, employment outcomes for refugees are also worse for women. Even though the majority of working-age refugees are women and more households are headed by women, employment rates were lower for women than men before COVID (19% versus 21% in Kakuma, 36% versus 43% in Kalobeyei). Even among those women who are employed, they tend to occupy lower paid jobs—including in volunteer positions, agriculture and informal activities—than their male counterparts who are more likely to be in paid employment work. Based on estimates collected by UNHCR and the World Bank in collaboration with the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics using the World Bank High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS), the pandemic has had a dramatic impact on the employment situation for most refugees, with women disproportionately impacted. Only 6% of camp-based refugee women were employed in Oct-Nov 2020 compared to 28% of refugee men, aggravating existing inequity in poverty and food insecurity for women and women-headed households (Kakuma SES 2019; Kalobeyei SES 2018).

As we mark International Women’s Day this week, these sobering statistics serve as a reminder to the global community that targeting gender-based inequity and vulnerabilities should always be a programmatic priority. Especially for fragile or vulnerable groups such as refugees, the COVID-19 pandemic has had disproprotionate negative impacts on women and girls, serving to only greater compound existing inequity in labour market outcomes, welfare, and education among others.